(1)

Hôpital Universitaire de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France

Abstract

It would be impossible to cover all cutaneous manifestations of medical emergencies. Here are some important signs indicating diseases that can be life threatening.

It would be impossible to cover all cutaneous manifestations of medical emergencies. Here are some important signs indicating diseases that can be life threatening.

14.1 Exanthemas and Erythematous Macules

Historically, the term exanthema was used to describe cutaneous lesions that occur in certain infectious diseases. Today, it is used to describe eruptive cutaneous lesions covering the whole integument or part of it. Enanthema is the mucous affection that may be associated to exanthema.

Kawasaki disease. Exanthema which is predominant in the bathing suit area (Fig. 14.1, case of Pr Boralevi, Bordeaux). Even though rare, this disease must always be considered when diagnosing a child with exanthema, especially between 1 and 5 years old (and regardless of the type of rash) (Fig. 14.2). Indeed, the prognosis of Kawasaki disease depends on early diagnosis and treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins and aspirin. If left untreated, up to 25 % of children develop serious aneurysmal cardiovascular complications. The criteria for diagnosis are high persistent fever (>5 days), conjunctivitis (Fig. 14.3), oropharyngeal involvement (cheilitis, saburral tongue which becomes depapillated and “strawberry-like”), edema of the extremities that is more or less erythematous (Fig. 14.4) (followed by characteristic periungual peeling of the skin in large scales, “en doigts de gant” in the French terminology), exanthema, and enlarged cervical lymph nodes. The location of the rash on the buttocks is characteristic (Fig. 14.1); however, the exanthema can be generalized, maculopapular (Fig. 14.2), diffuse and erythematous, or urticarial. BCG reactivation is classical (Fig. 14.5). The general condition is almost always strongly affected.

Fig. 14.1

∎ (Photos Courtesy of Pr Boralevi, Dermatology Department, University Hospital of Bordeaux)

Fig. 14.2

∎ (Photos Courtesy of Pr Boralevi, Dermatology Department, University Hospital of Bordeaux)

Fig. 14.3

∎ (Photos Courtesy of Pr Boralevi, Dermatology Department, University Hospital of Bordeaux)

Fig. 14.4

∎ (Photos Courtesy of Pr Boralevi, Dermatology Department, University Hospital of Bordeaux)

Fig. 14.5

∎ (Photos Courtesy of Pr Boralevi, Dermatology Department, University Hospital of Bordeaux)

Monomorphic papular exanthema; certain lesions displaying a darker center (Fig. 14.6). Chronic meningococcemia (case of Dr Cuny, in Nancy). Certain septicemias are chronic and may appear as an exanthema, such as in this example of type B chronic meningococcemia (Fig. 14.6); they may however become devastating. Hence the dogma of performing blood cultures in every patient with a febrile exanthema, especially when recurrent and associated to joint and/or tendon pain or to deterioration of the general condition.

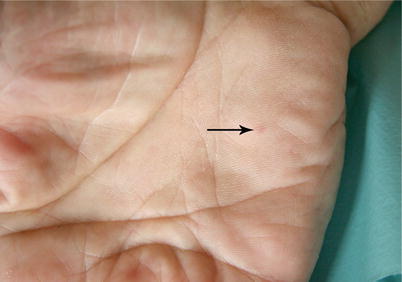

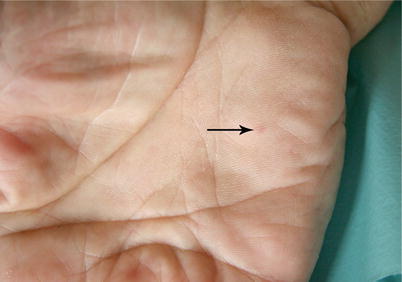

Hardly visible erythematous macule located on the palms (Fig. 14.7, arrow). Janeway lesion (infectious endocarditis). This sign is subtle and evanescent (<48 h), but very specific of subacute infectious endocarditis; in this case, the infection was caused by Streptococcus oralis, and it occurred after dental surgery. In endocarditis, palmar erythematous macules sometimes coexist with purpuric lesions (arrow) (Figs. 14.8 and 14.9). There is a continuum between the classic Janeway lesion (Fig. 14.7) and Osler’s nodes (cf. Fig. 14.12). The identification of these lesions can be lifesaving as it allows diagnosis of infectious endocarditis.

Fig. 14.6

(Photos Courtesy of Dr Cuny, Dermatology Department, University Hospital of Nancy)

Fig. 14.7

∎

Fig. 14.8

∎