Chapter 8 Dermatitis (eczema)

1. What is dermatitis and why is it so important?

Dermatologists use the interchangeable terms “dermatitis” or “eczema” to refer to a specific group of inflammatory skin diseases. Dermatitis presents with pruritic, erythematous macules, papules, vesicles, or plaques with or without distinct margins. Lesions pass through acute (vesicular), subacute (scaling and crusting), and chronic (acanthotic with thick epidermis) phases. Oozing, crusting, scaling, fissuring, and lichenification frequently accompany the primary lesions. Up to 25% of all patients presenting with a new skin disease have a form of dermatitis. Patients typically suffer from intense pruritus that distracts them from their daily activities, including sleep, and they are desperate for relief.

2. What is atopy?

Atopy is derived from the Greek word atopos, meaning “out-of-place,” and refers to the predisposition to develop dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis. The surfaces where the body contacts the external environment are “overreactive” (the lower airways in asthma, the upper airways and conjunctiva in allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and the skin in atopic dermatitis).

3. Why is atopic dermatitis becoming more common?

The prevalence of atopic dermatitis in six- and seven-year-old children varies from less than 2% in Iran and China to 10% to 20% in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and Scandinavia. The incidence was only 2% in those born before 1960. The increase over time and difference between more- and less-developed nations has been explained by the “hygiene hypothesis.” This postulates that a reduction in the frequency of childhood infections results in an increased incidence of various allergic and autoimmune diseases including atopic dermatitis, asthma, allergic rhinitis, childhood insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and Crohn’s disease.

4. What are the diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis?

5. What is the underlying defect in patients with atopic dermatitis?

At least 50% of patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis have a defect in the gene coding for filaggrin, a protein essential to maintaining the barrier function of the stratum corneum. The stratum corneum then allows various irritants, microbes, or allergens to penetrate the skin surface, elicit cytokine release from keratinocytes, and initiate a Th2 immune response acutely that leads to the clinical manifestations of disease and increased IgE levels. In chronic cases of atopic dermatitis, the Th2 response is replaced by a Th1 response. A primary immune defect, at least in some atopic patients, cannot yet be ruled out because bone marrow stem cell transplants from atopic patients have transferred atopic dermatitis to recipients.

7. Why does atopic dermatitis itch?

Neural and chemical mechanisms are involved. When the epidermis and its nerve fibers are stripped from skin, pruritus is abolished. Keratinocytes and mast cells release high levels of nerve growth factor (NGF), which increases the sensitivity of cutaneous pruritus receptors. These sensitized nerve endings demonstrate an increased capacity to transmit signals that are perceived as pruritus (allokinesis). Chemical mediators associated with itch include serine proteases, interleukins 2 and 31, opioids, acetylcholine, prostanoids, and substance P. Histamine may play a limited role in the pruritus of atopic dermatitis. These mediators act either on nerve endings or directly on keratinocytes. They are produced by mast cells, keratinocytes, T cells, and nerve fibers.

8. Why do people like to scratch an itch?

Scratching suppresses areas of the brain associated with negative experiences of pruritus and activates pleasure centers of the brain. In other words, there is an emotional reward for scratching. Unfortunately, scratching damages the skin and worsens dermatitis so that it itches even more. Therefore, people scratch even more and get caught in an “itch-scratch cycle” that they cannot exit without medical help or supreme levels of self-restraint.

9. Does psychological stress worsen atopic dermatitis?

Probably. In mice, various stressors can produce atopic dermatitis skin lesions, possibly due to an upregulation of substance P–sensitive nerve fibers. Transepidermal water loss increases in humans who are under mental stress compared to control subjects. Such water loss is an indicator of a defective epidermal barrier.

10. Did John Phillip Sousa write the “Atopic March?”

No, but if he did, it would have a lot of scratching, sneezing, and wheezing coming from the percussion section! The atopic march is not music but the subsequent development of allergic rhinitis (70%) and/or asthma (50%) in patients with atopic dermatitis. Filaggrin mutations predispose to airway disease in atopic dermatitis patients. Evidence points to the necessity of epicutaneous exposure to allergens (e.g., dust mites) that cause allergic airway disease in these patients. If infants with atopic dermatitis have good barrier protection, it is likely that the airway disease of the atopic march can be prevented!

11. How does atopic dermatitis present at different ages?

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Atopic dermatitis may present at any age, but 60% of patients experience their first outbreak by their first birthday, and 90% by their fifth. Four clinical phases are recognized:

1. Infantile (2 months to 2 years)

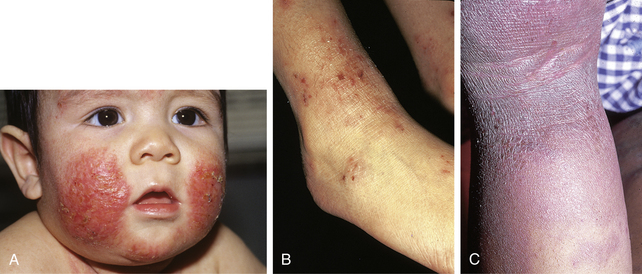

• Distribution: Cheeks (Fig. 8-1A), face and scalp, extensor surfaces of extremities and trunk (due to friction from crawling)

2. Childhood (3 to 11 years)

• Distribution: Wrists, ankles, backs of the thighs, buttocks, and antecubital and popliteal fossae (Fig. 8-1B)

• Morphology: Chronic, lichenified scaly patches and plaques that may have crusting and oozing (see Fig. 8-1B)

4. Adult (>20 years)—50% of all patients will have recurrences as adults

• Distribution: Most commonly involves the hands, sometimes the face and neck, and rarely diffuse areas