, Paul N. Chugay1 and Melvin A. Shiffman2

(1)

Long Beach, CA, USA

(2)

Tustin, CA, USA

Abstract

The authors focus on the treatment of deltoid hypoplasia. The basic anatomy of the region is described and preoperative marking, indications, and contraindications are discussed. The operative procedure is described as well as postoperative care and potential postoperative complications. Observed complications are described with the management of those complications.

Introduction

Trauma, oncologic surgery, and congenital conditions can alter the appearance of the shoulder girdle and produce noticeable asymmetries of the upper extremity. To that end, the author (NVC) designed a prosthesis to help in recontouring the deltoid region and help patients attain greater symmetry between the two arms. In addition, increased publicity given to sculpted physiques has driven many men in search of a more muscular appearance. Despite rigorous workout regimens, some men are not able to gain the volume and definition that they desire in the deltoid region. For that patient, a deltoid implant may help in giving a more muscular appearance.

History of the Procedure

Orthopedic surgeons and plastic surgeons have long dealt with congenital anomalies of the shoulder and injuries to the brachial plexus that produce degeneration of the deltoid muscle and leave asymmetry between the two arms. Silicone prostheses have been used in these cases to help maintain the shape of the arm and achieve greater symmetry between affected and unaffected sides.

Of the known congenital anomalies of the shoulder girdle, Sprengel’s disease is the most discussed in the literature, despite its rare occurrence. It results in a congenitally high scapula due to inadequate caudal movement of the scapula during development. Although there is no way to create absolute symmetry between an affected and an unaffected arm, the use of orthopedic procedures such as the Green technique and Woodward technique to reattach the overlying musculature and reposition the bone is the standard of care [1]. Some surgeons have even moved to using artificial silicone grafts to help bridge the gap to a good cosmetic outcome. Saray et al. [2] treated a patient with Sprengel deformity in 2000 using a silicone calf implant, hoping to bring about a more cosmetically appealing result. As noted by Saray, the “orthopedic procedures to correct Sprengel deformity are usually inconsistent and cosmetic results are far from satisfactory.” To this end, he and his team set out to correct the patient’s “sagging look,” which was attributed to trapezius hypoplasia, with a calf implant. A 60 mL calf implant was then placed into a subcutaneous plane via a thyroidectomy-type incision in the neck.

In 2006, Hodgkinson described his work with deltoid reconstruction in patients that had deltoid degeneration following axillary nerve injury [3]. The axillary nerve in trauma victims is typically injured during a significant stretch of the brachial plexus, with disruption of the nerve as it exits the quadrilateral space in the axilla. There have also been cases of iatrogenic axillary nerve injury associated with shoulder operations or fracture reduction [3–6]. The result of these traumatic or iatrogenic injuries is a flattening of the natural convexity of the deltoid region and a weakening of the arm’s ability to abduct. Hodgkinson fashioned custom implants for each patient based on a moulage preparation of the unaffected deltoid region. This custom-made implant is then placed below the deltoid muscle to help bring symmetry to the two sides.

In 2011, the primary author (NVC) began his work in creating a custom deltoid implant for cosmetic augmentation of the lateral shoulder region. Although the work began on a patient with Sprengel’s deformity, subsequent patients merely had hypoplastic deltoid regions and wanted to add volume to achieve a more “bulked up” appearance. Using a technique similar to that employed by Hodgkinson for reconstruction of the deltoid region, the primary author places a custom-made Chugay deltoid implant beneath the deltoid muscle, onto the upper humerus. With this augmentation, patients can expect to see a horizontal increase in volume of approximately 1 in. (2.54 cm) per side.

Indications

The primary indication for deltoid augmentation is correction of unilateral defects coming from trauma, oncologic surgery, and congenital anomalies. Congenital abnormalities of the skeleton, such as Sprengel’s deformity which results in one shoulder blade sitting higher than the other, can be treated by performing a unilateral deltoid augmentation to bring greater symmetry to the body, particularly in the lateral aspect. Muscular dystrophies and traumatic injuries to the brachial plexus which result in hypotonia to muscles of one arm can similarly be treated with a unilateral deltoid implant to create a more symmetric appearance to the upper extremities. An alternative indication for the procedure may be for augmentation of the deltoid region for purely aesthetic reasons.

Contraindications

A relative contraindication to the procedure is a history of keloid or significant hypertrophic scarring. The deltoid region, along with the pectoral and back regions, is known to have one of the highest occurrences of keloid and hypertrophic scarring [7]. In light of this fact, a person that is already prone to this condition may be a poor candidate for surgery as the risk is already high even without a known predisposition.

Limitations

Augmentation of the shoulder region does not improve function of the muscles of the upper extremity. Patients who present with conditions due to trauma or congenital abnormalities need to understand that the change will be purely cosmetic and will have no improvement in mobility or function of the affected limb.

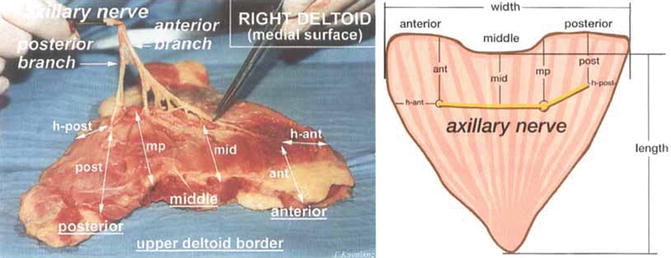

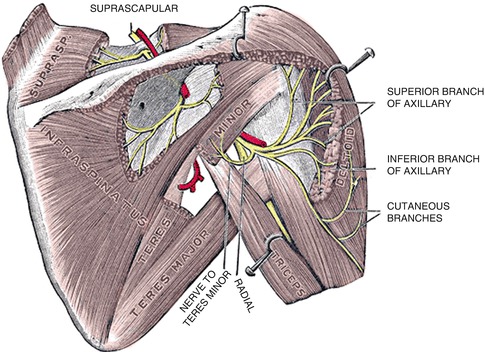

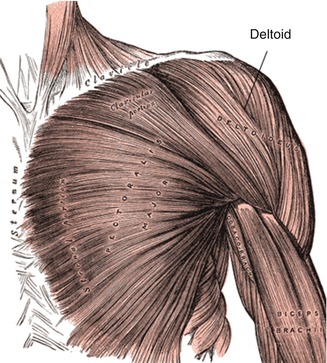

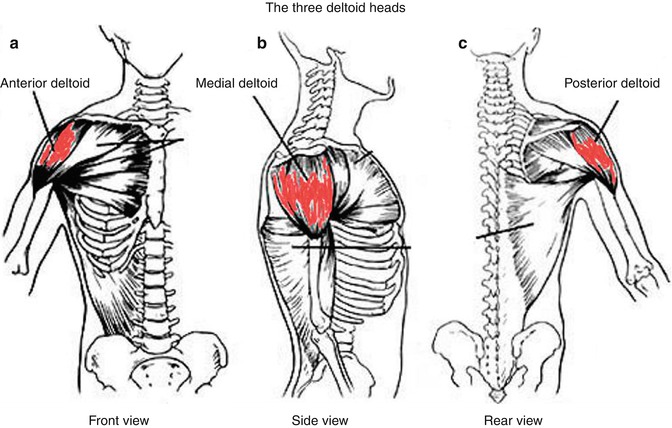

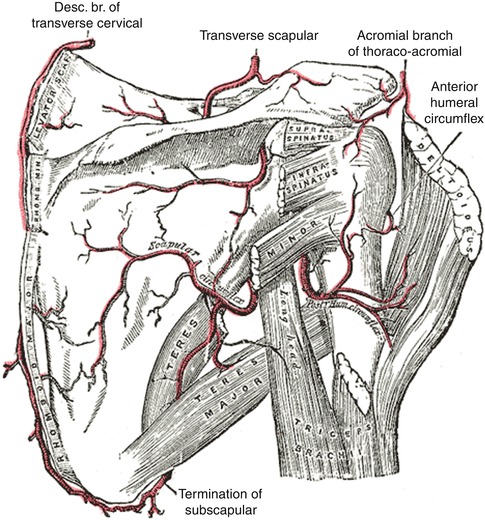

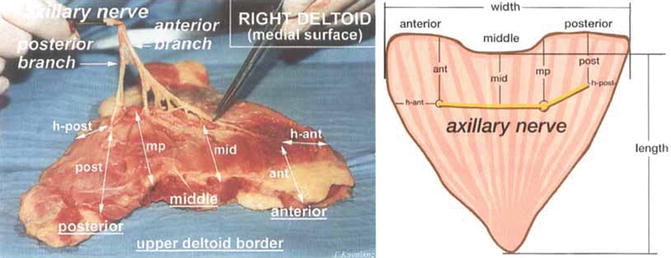

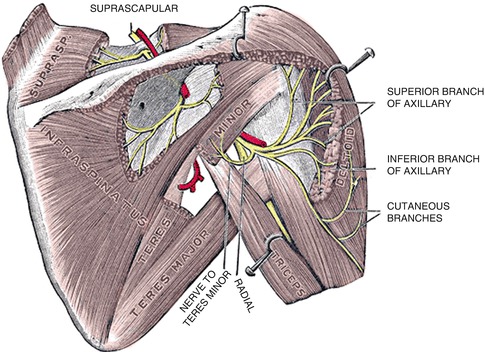

Relevant Anatomy

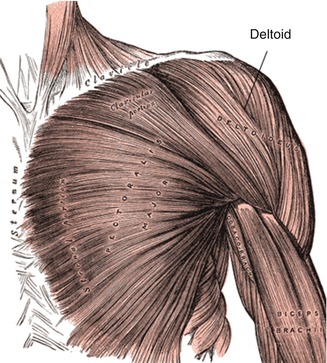

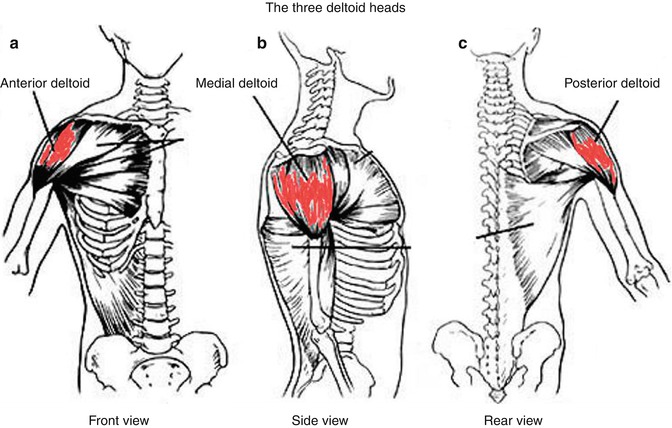

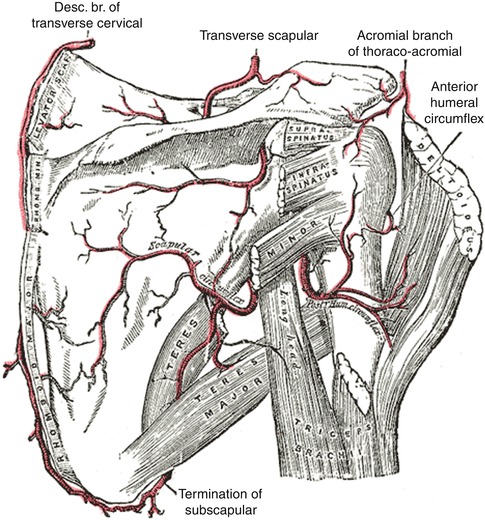

The deltoid muscle, or deltoideus, is a triangular-shaped muscle that is responsible for providing the rounded shape to the shoulder region (Fig. 9.1). Rather than being one solid muscle, the deltoid muscle is actually composed of three distinct muscles, as proven in anatomic and electromyographic studies (Fig. 9.2) [8]. A study of 30 shoulders revealed an average weight of 191.9 g (range 84–366 g) in humans [9]. The deltoid is made up of three heads: anterior (clavicular), lateral (middle, acromial), and posterior (spinal). The three heads all insert onto the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus. The anterior and lateral heads originate on the clavicle, while the posterior head has its origin on the inferior margin of the spine of the scapula (acromion). While the anterior deltoid often works in synergy with the pectoral muscles in movements of horizontal flexion and medial rotation of the humerus, the lateral deltoid is dedicated to abduction of the humerus at the shoulder joint and the posterior deltoid works in concert with the back muscles such as the teres major and rhomboids to perform horizontal extension and lateral rotation of the humerus. The pectoralis major and the anterior deltoid muscle are closely related and only separated by a small chiasmatic space which allows for the passage of the cephalic vein, preventing the two muscle from being one continuous muscle mass [8]. The deltoid muscle is supplied by the posterior circumflex humeral artery, which arises from the axillary artery. This artery travels posteriorly with the axillary nerve through the quadrangular space of the axilla (Fig. 9.3). The three heads of the deltoid are innervated by the axillary nerve, which arises from the ventral rami of C5 and C6 cervical nerves (Fig. 9.4) [9–11]. Again, this nerve enters from the posterior aspect of the muscle from the axillary region and runs along the medial surface of the muscle. Many orthopedic surgeons recommend that the separation of the deltoid fibers should occur no more than 4 cm from the tip of the acromion as injury to the axillary nerve is a possibility. This has been confirmed in anatomic studies that identify the axillary nerve as being located about 4.6 cm from the tip of the acromion (range 2–6 cm) (Fig. 9.5) [12]. Based on this and other research on the split lateral deltoid approach, it is safe to say that the safe zone for the dissection for placement of a deltoid implant is within 5 cm of the acromion, leaving an area of 5–9 cm below the acromion as a danger zone for potential axillary nerve injury [13].

Fig. 9.1

Deltoid muscle overlying shoulder girdle and adjacent muscles

Fig. 9.2

Three heads of deltoid muscle

Fig. 9.3

Blood supply to the deltoid

Fig. 9.4

Axillary nerve distribution

Fig. 9.5

Anatomic dissection of the deltoid muscle and the axillary nerve at its superior border within 5–6 cm of the acromion

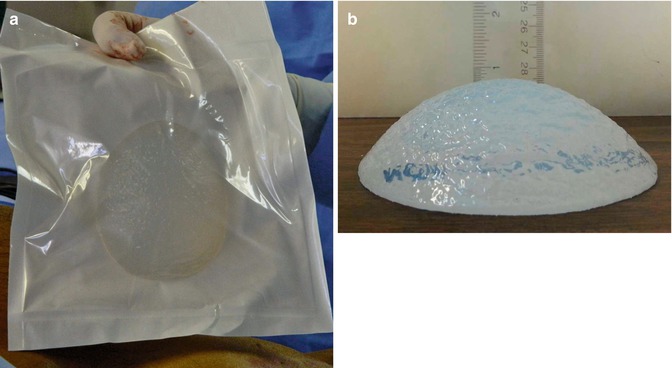

Consultation/Implant Selection

A thorough history and physical examination are paramount to preventing complications at the time of deltoid augmentation. During the consultation, patient’s expectations are managed and assessment of the patient’s mental state is undertaken. It is made clear to the patient the expected augmentation that can be seen with the surgery and limitations of the procedure are also explained (Fig. 9.6). Risks of the procedure, particularly injury to the axillary nerve, are discussed. A person with a notably short deltoid length is at greater danger of damaging the axillary nerve at a short distance from the upper border of the muscle [12].

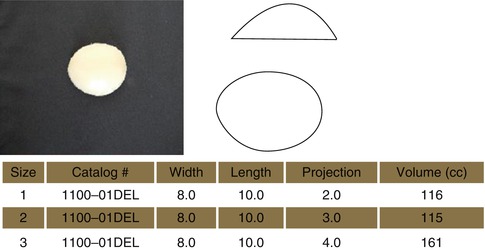

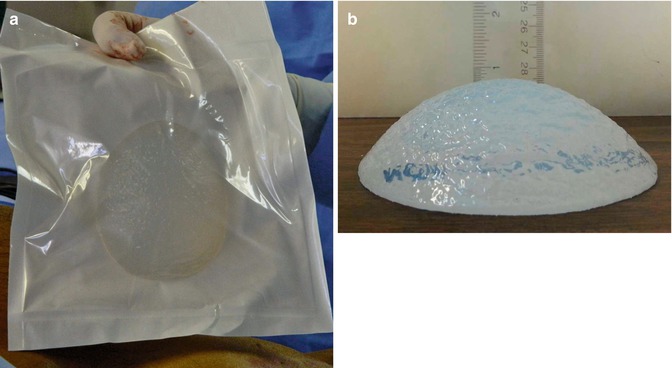

Fig. 9.6

(a) The deltoid implant in its packaging prior to implantation. (b) Deltoid implant lying flat on the table demonstrating vertical height of approximately 1 inch

After completion of the history portion of the consultation, an evaluation of the patient’s deltoid is made. Any asymmetries or defects are pointed out to the patient. The patient’s muscles are then evaluated. The patient is asked to demonstrate a full range of motion of the shoulder girdle and arm to assess for any preexisting nerve injury or palsy. The skin and fat content are similarly assessed at this time as a patient with minimal adipose and thin skin is more at risk for implant palpability. Measurements of the patient’s deltoids are then taken: (1) vertical height (length of the muscle) being measured from the level of the acromion to the suspected insertion over the humerus and (2) horizontal expanse of the deltoid (width of the muscle) as noted by palpation of muscle volume.

Preoperative Planning and Marking

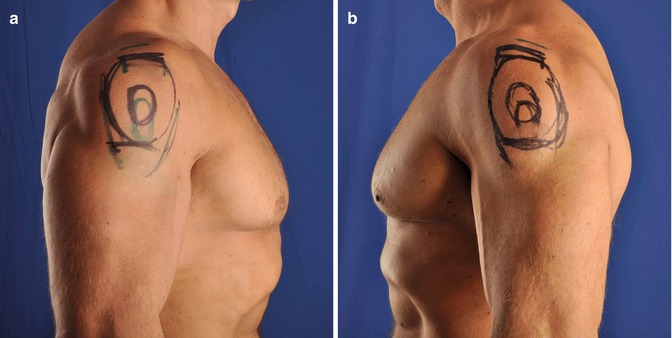

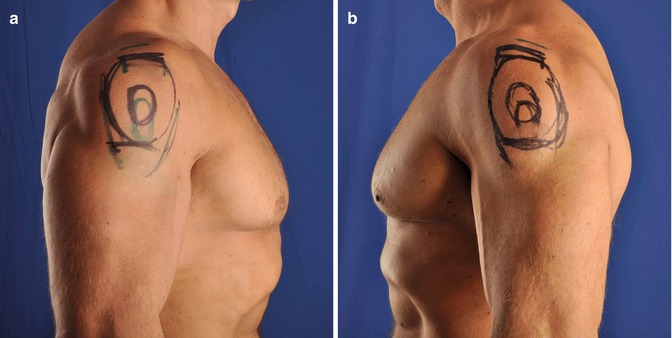

On the day of the surgery, the patient is met in the preoperative holding area. It is here that the patient’s consent is verified and again risks, benefits, and alternatives are reviewed with the patient. With the patient in the erect position, the proposed site of incision is marked, measuring approximately 5–7 cm. The site of incision should be in the upper arm, overlying the deltoid muscle and 2 cm below the palpated glenohumeral joint, but being careful to not place the incision too low as axillary nerve injury can be caused with a low lying split of the deltoid muscle (Fig. 9.7). Once the site of the incision is marked, the site of the proposed implant is marked taking into account the patient’s anatomy and existing deficit along with the desires of the patient.

Fig. 9.7

(a, b) Preoperative markings in patient undergoing bilateral deltoid augmentation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree