Chapter 32 Deep fungal infections

1. What is a deep fungal infection?

In contrast to the superficial dermatophytes, which are typically confined to dead keratinous tissue, certain mycotic infections have the capacity for deep invasion of the skin or production of skin lesions secondary to systemic visceral infection. They are typically acquired through direct inoculation, ingestion, and/or inhalation of spores from soil or matter. In this chapter, the deep fungal diseases are organized into three categories based on clinical presentation (Table 32-1).

Table 32-1. The Deep Fungal Infections

| SUBCUTANEOUS FUNGAL INFECTIONS | SYSTEMIC OR RESPIRATORY FUNGAL INFECTIONS | OPPORTUNISTIC FUNGAL INFECTIONS |

|---|---|---|

Subcutaneous fungal infections

2. Discuss the characteristics of subcutaneous mycotic infections.

Subcutaneous mycotic infections are caused by a heterogeneous group of fungi and are infections of implantation (inoculated directly into the skin through local trauma). The four most important infections are sporotrichosis, chromomycosis, phaeohyphomycosis, and mycetoma. Lobomycosis and rhinosporidiosis are significantly less common. As a group, these infections involve primarily the skin and subcutaneous tissues and rarely disseminate to produce systemic disease in the immunocompetent host. These organisms are ubiquitous in soil, plants, and trees.

4. What occupations are at increased risk of sporotrichosis?

Sporotrichosis is caused by a dimorphic fungus, Sporothrix schenckii. This organism is found worldwide, except in polar regions, and is most common in subtropical and tropical climates. It is endemic in Africa and Central and South America. In the United States, infection is most common in the Midwest. The normal habitat includes soil, thorny plants (especially roses), hay, sphagnum moss, and animals. Cats may carry Sporothrix on their paws and can cause infection by scratching their owners or animal handlers. A cat-transmitted epidemic was reported in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Occupations at risk of cutaneous inoculation include farmers, gardeners (especially rose), florists, masonry workers, Christmas tree farmers, veterinarians, and animal handlers (especially cats, rodents, and armadillos).

5. Describe the clinical manifestations of sporotrichosis.

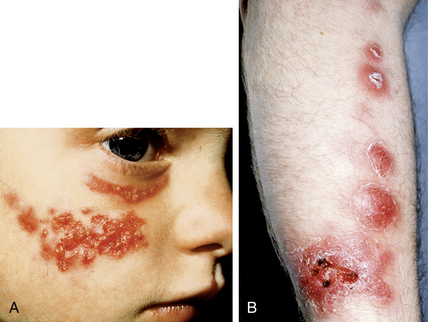

Cutaneous sporotrichosis is more common than systemic sporotrichosis. Cutaneous sporotrichosis can be further divided into two forms: lymphangitic or lymphocutaneous disease, and fixed infection. The lymphocutaneous form accounts for approximately 80% of the cases. This classic form of sporotrichosis begins at the site of inoculation (most commonly, upper extremity) as a painless pink papule, pustule, or dermal nodule, which rapidly enlarges and ulcerates (Fig. 32-1A). Without treatment, the infection ascends along the lymphatics, producing secondary nodules and regional lymphadenopathy that may ulcerate (Fig. 32-1B). The fixed cutaneous variant (20%) is confined to the site of inoculation. The organism may rarely disseminate hematogenously to the joints, bone, meninges, or eye. Disseminated disease is most common in immunosuppressed patients, especially those with impaired cellular immunity (acquired immune deficiency syndrome [AIDS] patients). Pulmonary disease is usually due to inhalation and generally occurs in alcoholics, immunocompromised or debilitated patients. Both erythema nodosum and erythema multiforme have been reported as reactive eruptions to sporotrichosis.

6. How is the diagnosis of cutaneous sporotrichosis made?

A strong clinical suspicion is most important. Skin biopsy shows granulomatous inflammation with neutrophilic microabscess formation. In the immunocompetent patient, fungal elements are typically not found even with special fungal stains: periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) stains. Therefore, when suspecting sporotrichosis, cultures on Sabouraud’s medium are confirmatory. Colonies grow rapidly in 3 to 5 days.

7. How do you treat cutaneous sporotrichosis?

Itraconazole (100 to 200 mg/day) for 4 weeks after clinical cure is the treatment of choice for lymphocutaneous, fixed cutaneous, and disseminated cutaneous sporotrichosis, with a success rate of 90% to 100%. Terbinafine (1000 mg/day) is second-line treatment, and because potassium iodide (SSKI) is less costly than other agents, it is still recommended, especially in developing-world epidemics. Fluconazole (200 mg/day) and local hyperthermia have also been shown to be effective. Children may be safely treated with itraconazole.

8. What other organisms may present with lymphocutaneous disease?

Several other diseases may present with a distal ulcer, proximal secondary nodules along the lymphatics, and regional lymphadenopathy. The most important organisms include nontuberculous Mycobacterium (Mycobacterium marinum, Mycobacterium kansasii, Mycobacterium fortuitum complex), Nocardia, leishmaniasis, cat scratch disease, and tularemia. A patient with this clinical presentation should have tissue biopsies for routine histology and cultures to include bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi. This pattern of disease is also called sporotrichoid.

9. What are dematiaceous fungi?

Dematiaceous fungi are black pigmented fungi. They are slow growing and can be found in the soil, decaying vegetation, rotting wood, and the forest carpet. Subcutaneous-cutaneous disease is caused by traumatic inoculation into the skin. There are three broad categories of dematiaceous fungal infections including chromomycosis, phaeohyphomycosis, and eumycotic mycetoma (Madura foot).

10. How do you differentiate chromomycosis from phaeohyphomycosis?

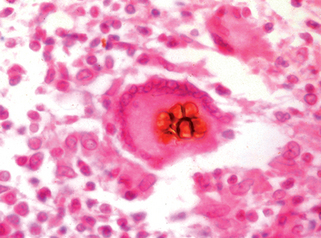

Chromomycosis is a chronic subcutaneous infection characterized by the appearance in tissue biopsies of an intermediate, vegetative, pigmented fungal form with a yeastlike appearance that is arrested between yeast and hyphal formation. These pigmented, thick-walled fungal elements are called Medlar bodies (Fig. 32-2). Medlar bodies, also called copper pennies or sclerotic bodies, are diagnostic of chromomycosis, differentiating it from phaeohyphomycosis. Tissue biopsies of phaeohyphomycosis are characterized by lightly pigmented filamentous hyphae.

11. Which organisms may cause chromoblastomycosis?

12. Which organisms cause phaeohyphomycosis?

Phaeohyphomycosis may occur in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. Due to the increasing immunocompromised patient population, there has been an increased number of fungi in this class that cause disease. Phaeohyphomycosis has been attributed to >60 genera and >100 species. The most important genera include Scedosporium (Pseudallescheria), Alternaria, Bipolaris, Curvularia, Exophiala, Phialophora, and Wangiella.

13. How does chromomycosis present?

Chromomycosis is a chronic cutaneous and subcutaneous infection that is usually present for years with minimal discomfort. The inciting injury is often not remembered. The infection is most common on the lower extremity and 95% of cases occur in males. The typical patient is a barefoot, rural agricultural worker in the tropics. At the site of inoculation, red papules develop that eventually coalesce into a plaque. The plaque slowly enlarges and acquires a verrucous or warty surface. Satellite lesions can develop from extension of the infection through scratching. There may also be secondary bacterial infections of the lesion. If the lesion is not treated, it can evolve into a cauliflower-like mass, leading to lymphatic obstruction and elephantiasis-like edema of the lower extremity (Fig. 32-3). Neoplastic transformation to squamous cell carcinoma can occur. Diagnosis is made through potassium hydroxide (KOH) mounts from scrapings, biopsies of the lesions showing the organism and suppurative and granulomatous inflammation, and culture. Rare reports of hematogenous dissemination to the brain have been made. Chromomycosis is typically resistant to treatment. The treatment of choice for small lesions is surgical excision with a wide margin of normal skin. Chronic or extensive lesions should be treated with a combination of itraconazole therapy and surgical excision. Combination therapy with terbinafine, posaconazole, cryotherapy and local heat therapy also appear to be effective. Treatment is continued for months.

14. Describe the clinical features of phaeohyphomycosis.

The spectrum of clinical infections is broad. The most typical presentation is a subcutaneous cyst or abscess at the site of trauma and Exophiala jeanselmei is the most common organism. The primary lesion is a painless nodule. The nodule evolves into a fluctuant abscess. Immunocompromised patients present with multiple nodules. Dissemination is rare; however, the incidence has increased over the past 10 years. Scedosporium proliferans (42% cases), Bipolaris spicifera (8%), and Wangiella dermatitidis (7%) are the most common causes of disseminated disease. The primary risk factor is decreased host immunity, especially prolonged neutropenia. The outcome is poor, despite antifungal therapy, with an overall mortality rate of 79%. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis acquired through inhalation and hematogenous dissemination is most commonly seen in immunocompetent persons with no obvious risk factors.

15. What is Madura foot?

Madura foot, a type of mycetoma, is a localized, destructive infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that eventually involves deeper structures, such as muscle and bone. It may be caused by both filamentous bacteria and aerobic actinomycetes (actinomycetomas) and true fungi (eumycetoma). The most common causative fungi are Madurella mycetomatis and Madurella grisea. Less frequent causes are Acremonium kiliense, E. jeanselmei, and Scedosporium apiospermum (also called Pseudallescheria boydii).

16. What are the clinical features of Madura foot?

Madura foot is an indolent localized painless infection with three characteristic features. The first is the formation of nodules in the skin at the site of inoculation, usually a penetrating injury. The second feature is purulent drainage and fistula formation. The third and most characteristic feature is the presence of grains or granules that are visible in the purulent drainage. Seventy percent of cases involve the lower extremity, the foot in particular. Other sites of infection include the hand, head, back, and chest. Madura foot is a progressive infection leading to marked swelling and deformity in its latter stages (Fig. 32-4). Additionally, the lesions have a tendency to become painful in the latter stages, when bone involvement and deformity ravage the site. Eumycetomas are extremely difficult to manage and include medical, surgical, or a combination of both. Itraconazole and terbinafine are the most commonly used antifungal agents and are more effective than ketoconazole.

Figure 32-3. Chromomycosis. Cauliflower-like nodules and tumors on the foot and ankle with edema.

(Courtesy of James E. Fitzpatrick, MD.)