ORBITAL DECOMPRESSION

John L. Wobig and Roger A. Dailey

The boundaries of the orbit usually consist of rigid bone or foraminal openings with little or no compressibility. The significant exception is the anterior border, which consists of a semidispensable fascia in the form of the orbital septum and the globe, which is limited in its anterior movement by the optic nerve and extraocular muscle connections. Because of these anatomic constrictions, anything that takes up space in the orbit will cause the globe and orbital septum to move forward to “decompress” the orbit and prevent pressure from building within its bony walls. Once the limits of this natural decompression have been met, the hydraulic pressure in the orbital compartment builds, and the patient experiences increasing pain and sometimes nausea if pressure is building acutely. If the intraorbital pressure gets high enough, the blood supply to the eye will be compromised and the patient can suffer total loss of vision. Removal of orbital bone will result in increasing the volume of the bony orbit and relief of pressure exerted on the soft tissues.

There are a variety of etiologies for increased intraorbital pressure, including infection, inflammation, tumor, and hemorrhage. The most common indication for bony orbital decompression in oculoplastic practices is thyroid-related immuneorbitopathy (TRIO). In TRIO the soft tissue volume is increased by enlarging extraocular muscles and an increased volume of orbital fat due to the increasing stores of glycosaminoglycans and mucopolysaccharides.

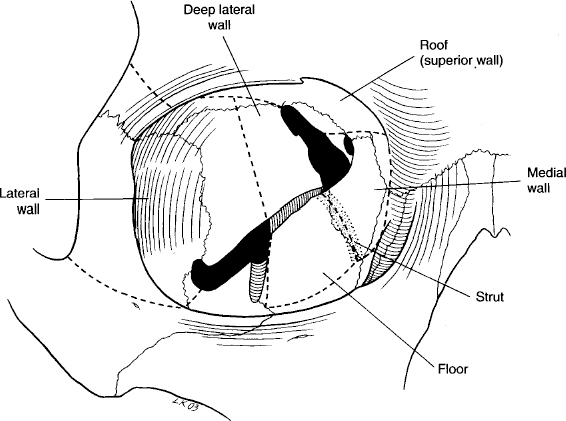

In TRIO, the indications for decompression are compressive optic neuropathy, spontaneous prolapse of the globe, exposure keratopathy inadequately responsive to more conservative management mea sures, and chronic pressure with related pain and discomfort, and as a first step in the reconstructive rehabilitation of the thyroid patient with moderate to marked proptosis. One-, two-, three-, and four-wall decompressions have been described (Fig. 17-1). Four-wall decompression involves removal of the superior orbital bone via a craniotomy and is rarely if ever used. The location and amount of bone removal constitute a judgment call by the surgeon based on experience. In general, a patient with compressive optic neuropathy requires posterior medial wall decompression at a minimum, and the more proptosis the patient has, the more bone must be removed to return the eyes to their former position. Our preferred method of decompression for the vast majority of patients is a “balanced” decompression involving mainly the lateral and medial walls. The posterior orbital floor can be added in patients with more significant proptosis or to identify the posterior maxillary sinus wall as a landmark to help gauge the posterior extent of ethmoid lamina resection. This approach allows the formation of a “strut” at the ethmoid-maxillary junction and has yielded the lowest incidence of postoperative diplopia, globe dystopia, and paresthesias.

Patients with mild to moderate proptosis without compressive optic neuropathy can be treated with decompression of just the lateral wall. This involves not only the removal of the anterior lateral wall (as described following here) but the deep lateral wall as well. This consists of removal of the bulk of the greater wing of the sphenoid and the lesser wing of the sphenoid anterior to the tip of the superior orbital fissure, including the fossa of the lacrimal gland. Three areas of bone deep within the lateral orbit that can be removed have previously been described.

FIGURE 17-1 Dotted lines indicate the four walls of the orbit considered for orbital decompression.

BALANCED ORBITAL DECOMPRESSION

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree