(1)

Hôpital Universitaire de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France

15.1.1 Behçet’s Disease

15.1.2 Lupus Erythematosus (LE)

15.1.3 Dermatomyositis

15.1.4 Systemic Sclerosis

15.1.5 Vasculitis

15.1.6 Sarcoidosis

15.1.9 Pyoderma Gangrenosum

15.1.10 Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome

15.1.11 Chilblain

15.1.12 Morphea

15.2.1 Xanthomas

15.2.2 Pretibial Myxedema

15.2.3 Acanthosis Nigricans

15.2.4 Pellagra

15.3.2 Mastocytosis

15.4 Paraneoplasias

15.4.1 Ichthyosis

15.5.1 Cowden Syndrome

15.5.2 Muir-Torre Syndrome

15.5.3 Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome

15.6.1 Neurofibromatosis

15.6.4 Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum

15.6.5 Rendu-Osler Disease

15.6.6 Fabry Disease

Abstract

Genital aphthosis. Behçet’s disease (Fig. 15.1). Mouth and genital ulcers (“bipolar aphthosis”), as well as pustules on an erythematous (Fig. 15.2) and/or purpuric background, are the most suggestive cutaneous signs of this systemic autoinflammatory disease. It particularly involves a risk of thrombophlebitis, aneurysms, uveitis, and inflammation of the central nervous system. Superficial thrombophlebitis (Fig. 15.3) is also more frequent in this disorder. The thrombosed vein can be localized on palpation.

15.1 Systemic Inflammatory Diseases

15.1.1 Behçet’s Disease

Genital aphthosis. Behçet’s disease (Fig. 15.1). Mouth and genital ulcers (“bipolar aphthosis”), as well as pustules on an erythematous (Fig. 15.2) and/or purpuric background, are the most suggestive cutaneous signs of this systemic autoinflammatory disease. It particularly involves a risk of thrombophlebitis, aneurysms, uveitis, and inflammation of the central nervous system. Superficial thrombophlebitis (Fig. 15.3) is also more frequent in this disorder. The thrombosed vein can be localized on palpation.

Fig. 15.1

Fig. 15.2

Fig. 15.3

Fig. 15.4

15.1.2 Lupus Erythematosus (LE)

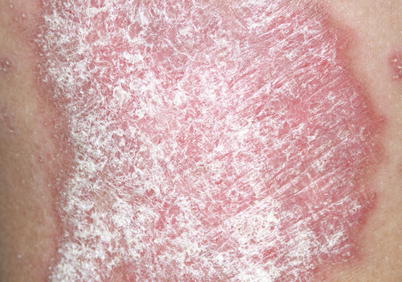

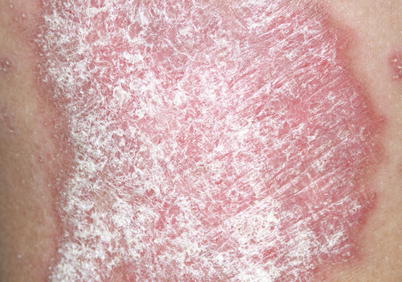

Malar rash (vespertilio erythema or “butterfly rash”). Acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus (Fig. 15.4). Cutaneous signs are common in this connective tissue disease which affects nearly all organs, particularly the joints, kidneys, serous membranes, heart, and central nervous system. Some cutaneous signs known as “specific lesions” allow diagnosing the disorder in the absence of other signs of the disease. Indeed, there is a particular histopathological aspect, namely, an interface dermatitis. The complex terminology of these cutaneous signs is a practitioner’s concern; only their specificity is of real importance. Other signs allow identifying a subgroup of patients particularly prone to thromboembolic and vascular complications. The main specific lesions are the malar rash (Fig. 15.4), psoriasiform (Fig. 15.5) and/or annular (Fig. 15.6) lesions of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and lesions of chronic lupus erythematosus (Fig. 15.7). The primary lesion in acute LE is a congestive erythema (Fig. 15.4) that can become scaly. In the course of acute lupus erythematosus, exanthema can be generalized (Fig. 15.8); the presence of lesions on extremities is common (Fig. 15.9). Periungual hyperaemia is a common sign (Fig. 15.10), particularly in infants. In subacute LE, the primary lesion is an erythema of leukodermic evolution, which is gray-white and telangiectatic (Fig. 15.6) and which can be psoriasiform (Fig. 15.5) and/or blistering and crusting, mainly on the borders (periphery) (Fig. 15.11). The following primary signs are associated with chronic LE: erythema, keratosis, dyschromia, and cutaneous atrophy (Fig. 15.7). The following lesions occur mainly in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus who are prone to thrombosis: livedo racemosa with non-infiltrated and large meshes (Fig. 15.12) or, conversely, acral fine livedo (Fig. 15.13), livedo vasculitis (Fig. 15.14), depressed porcelain-white papules as encountered in malignant atrophic papulosis or Degos disease (Fig. 15.15), non-infiltrated acral purpura (Fig. 15.16), and anetoderma (cf. Fig. 6.12).

Fig. 15.5

Fig. 15.6

Fig. 15.7

Fig. 15.8

Fig. 15.9

Fig. 15.10

Fig. 15.11

Fig. 15.12

Fig. 15.13

Fig. 15.14

Fig. 15.15

Fig. 15.16

15.1.3 Dermatomyositis

Erythema around the joint surfaces of the back of the hands, particularly the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints (Fig. 15.17). The cutaneous signs are extremely characteristic of this disorder and allow establishing diagnosis. These signs consist of an erythema which can be papular (Gottron’s papules) and is located above the metacarpophalangeal (Fig. 15.18) and proximal interphalangeal joints; these lesions may evolve towards crusting necroses (Fig. 15.19). They can also consist of a linear erythema of the back of the hands (cf. Fig. 1.1) or a flagellate erythema of the trunk (cf. Fig. 9.23), or also an erythema with a very peculiar violaceous coloration, evolving into poikiloderma on the knees, elbows, and/or eyelids (Fig. 15.20). The presence of mega-capillaries (submillimeter-sized telangiectasias) surrounding the nails is common (Fig. 15.21, arrows); a similar appearance can be observed in scleroderma. Semiological features in favor of this diagnosis are the violaceous color of the lesions, the presence of telangiectases, and the evolution into poikiloderma. Early diagnosis of dermatomyositis is important since this disorder exhibits several patterns of progression that are severe, including major muscle involvement (swallowing muscles, diaphragm, heart, etc.), a very severe interstitial lung disease, a risk of opportunistic infections (e.g., pneumocystosis), and associated cancer in approximately 15 % of cases.

Fig. 15.17

Fig. 15.18

Fig. 15.19

Fig. 15.20

Fig. 15.21

15.1.4 Systemic Sclerosis

Sclerosis of the hand accompanied by the complete disappearance of skin folds on fingers, as well as retracted fingers (Fig. 15.22). Systemic sclerosis is of complex pathogenesis and unknown cause. Several clinical forms exist and are characterized by a more or less diffuse hardening of the skin, which loses its suppleness (sclerosis). This situation is extremely crippling. The affection is predominant in extremities, and fingers end up retracting (Fig. 15.22); the face appears fixed (wrinkles have disappeared except around the mouth (Fig. 15.23)) and is covered with telangiectases. The groove sign is characteristic (Fig. 15.24). Patients with scleroderma almost always present with a Raynaud’s phenomenon (Fig. 15.25). They often develop digital ulcers. The presence of rectangular telangiectases on the face (Fig. 15.26) and fingers (Fig. 15.27) is typical. The last phalange must be carefully examined: mega-capillaries are present and there is periungual paleness and sometimes necrosis of the cuticles (Fig. 15.28); fusion of the nail plate with the periungual skin (pterygium) is typical (Fig. 15.28). A pigmentation disorder also exists, with a shiny hypopigmentation, particularly visible on pigmented skin (Fig. 15.29).

Fig. 15.22

Fig. 15.23

Fig. 15.24

Fig. 15.25

Fig. 15.26

Fig. 15.27

Fig. 15.28

Fig. 15.29

15.1.5 Vasculitis

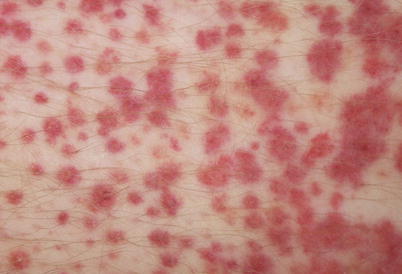

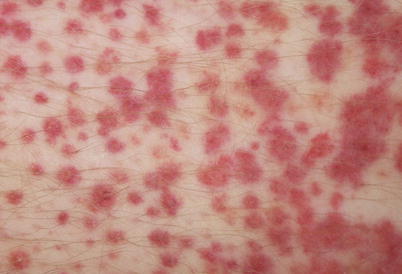

Palpable purpura. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Fig. 15.30). Vasculitis can have several dermatological expressions which are outside the scope of this book. They consist of a group of diseases characterized by an inflammation of the vascular wall, which may cause thrombosis. All organs can be affected and mostly the skin, digestive tract, and kidneys. There are multiple variants of vasculitis, which are classified according to the size of the smallest affected vessel and the presence of certain antibodies (ANCA: anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies). The most common dermatological expression of all forms of vasculitis is an erythematous and/or purpuric papule (Fig. 15.30). The most common site is the leg, and lesions tend to merge. A necrotic or pustular evolution is possible. Periungual and digital, confluent millimeter-wide purpuric papules are characteristic of rheumatoid vasculitis (Fig. 15.31). An infiltrated livedo accompanied by papules or nodules suggests medium- or large-vessel vasculitis (Fig. 15.32).

Fig. 15.30

Fig. 15.31

Fig. 15.32

15.1.6 Sarcoidosis

Erythematous plaques which appear lupoid on diascopy (Figs. 15.33 and 15.34). Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease of unknown cause. Almost all organs can be affected, particularly the lungs, lymph nodes, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous manifestations are numerous, some of which are not specific, e.g., erythema nodosum (cf. Figs. 5.21 and 5.22). Other specific manifestations are characterized by a granulomatous infiltrate in the dermis and/or hypodermis. In such cases, diagnosis can be established through skin biopsy. The most classic forms are papules (small and large) and plaques. One of the characteristics of these lesions is their lupoid appearance on diascopy. It consists of a yellow coloration which becomes apparent when pressure is exerted on the lesion using a transparent object, which empties the blood contained therein (Figs. 15.33 and 15.34). Lesions are red or red-brown and can be telangiectatic (Figs. 15.35, arrows and 15.36). The affection of the face by erythematous plaques defines the clinical form known as “lupus pernio.” The affection of the sides of the nose is known as angiolupoid of Brocq and Pautrier (Fig. 15.36, cf. Fig. 35.7). The cutaneous affection of the nostrils commands the search for an endonasal affection which can become obstructive and justifies a general treatment. Finally, the infiltration of an old scar (Fig. 15.37) must firstly suggest sarcoidosis; such an infiltration can also be seen in recurrences of cancer and certain parasitoses (coccidioïdomycosis, sporotrichosis).