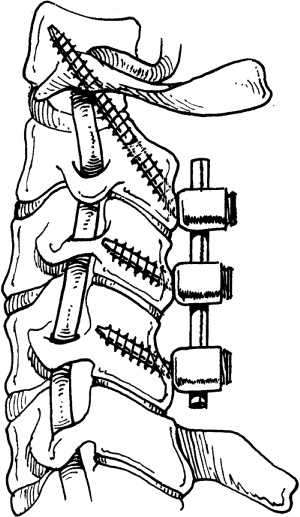

2 Cervical pathology can be treated effectively from both anterior and posterior approaches. Anterior cervical diskectomy has evolved to include interbody fusion. Plating technology, new interbody graft materials, and osteobiological materials have further advanced the anterior treatment of cervical disk disease. Posterior treatments are based upon either or both laminectomy and foraminotomy. The addition of lateral mass fusions helps prevent the complication of postlaminectomy kyphosis in patients at risk for this problem. The development of laminoplasty provides an alternative posterior technique that preserves cervical motion. The treatment of lumbar pathology is historically based on laminectomy for decompression. Some authors propose the addition of posterolateral fusions to treat mechanical back pain and prevent progressive instability in patients with spondylolisthesis or degenerative disk disease. In the early 1990s, posterolateral fusion with pedicle screw fixation was popularized for the treatment of low back pain due to spondylosis and spondylolisthesis. Posterolateral fusion with pedicle screw fixation earned an excellent track record. Lumbar interbody fixation has emerged as another option for spinal fusion in cases of spondylosis or spondylolisthesis. Arthroplasty and nonrigid fixation are also emerging as treatment options. Lumbar devices such as the Charité artificial lumbar disk (DePuy Spine, Raynham, MA) have already achieved U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval while other products remain in development. Cervical devices are being actively developed and hold great promise for preserving cervical motion. As recently as 1996, many authorities believed the majority of patients affected by nerve root or spinal cord compression secondary to cervical disk herniation or spondylosis were best served by anterior cervical diskectomy (ACD) alone.1 However, problems with postoperative neck pain and instability prompted the addition of fusion to this procedure. Given current technology for anterior cervical plating and numerous alternatives for interbody spacers, ACD without fusion is rarely performed in the United States today. Historically, laminectomy alone had been regarded as the standard posterior procedure for the treatment of multilevel cervical myelopathy in countries other than Japan. However, it fell into disfavor once sequelae such as segmental instability, kyphosis, perineural adhesions, and late neurological deterioration were recognized.2 Studies indicated that adding fusion to laminectomy added only modest operative time and morbidity, potentially arrested spondylosis at the treated levels, and reduced the incidence of postkyphotic deformity3 (Fig. 2–1). Cervical laminectomy and fusion utilizing lateral mass screws became popular, but its associated problems such as hardware failure, adjacent segment degeneration, and loss of range of motion led some to the utilization of laminoplasty. Posterior cervical laminoplasty, first popularized in Japan due to the unusually high incidence of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL), has many variations. The fundamental concept is the enlargement of the cervical canal without complete removal of the lamina while preserving cervical motion segments (Figs. 2–2 and 2–3). Proponents of laminoplasty believe the procedure preserves motion, reduces adjacent segment degeneration, and preserves the insertion points for the extensor muscles.2 Studies comparing the results of patients with cervical spondylitic myelopathy treated with either laminectomy and fusion or laminoplasty have been performed. Heller et al2 performed a retrospective analysis of laminectomy and fusion versus laminoplasty for the treatment of multilevel cervical myelopathy. Thirteen matched patients receiving either procedure were selected. Patients were matched by age, duration of symptoms, and Nurick grade. The authors concluded that patients receiving laminoplasty demonstrated greater improvements in Nurick scores with fewer operative complications.2,4,5 Figure 2–1 C2–C4 laminectomies with C1–C4 lateral mass fusion utilizing the Vertex Reconstruction System (Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN). Figure 2–2 Intraoperative photograph of a laminoplasty utilizing the Centerpiece Plate Fixation System (Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN). Posterior cervical foraminotomy is an option for decompression of foraminal nerve root compression. Open techniques were complicated by painful muscle-splitting incisions and prolonged recovery time secondary to muscle spasm. Minimally invasive techniques, including tube access and endoscopic technology, have opened the door to shorter recovery times and better patient tolerance. Fessler and Khoo reported on the use of microendoscopic foraminotomy (MEF) in 25 patients with cervical root compression from either foraminal stenosis or disk herniation. Twenty-six patients undergoing the standard open operation were used for a comparison. The MEF technique yielded patients with equivalent clinical results with less blood loss, shorter hospitalizations, and a much lower postoperative pain medication requirement.6 Figure 2–3 Lateral x-ray following a laminoplasty with the CenterPiece system (Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN). ACD with fusion (ACDF) was first described by Smith and Robinson7 and also by Cloward8 in the 1950s. The addition of fusion had reported benefits, including reduction of neural manipulation and neural injury, arrested spur formation or resorption of spurs in response to fusion, reduced posterior compression as a result of unbuckling the ligamentum flavum and the posterior longitudinal ligament, and increased neuroforaminal height.9 Initial attempts were performed without anterior plate fixation. Iliac crest autograft was usually placed as the interbody spacer. Although an excellent material to promote interbody fusion, it is associated with harvest site–related morbidity in up to 25% of patients. The potential for donor site infection and pain are limitations of its use.10 Consequently, allograft eventually replaced iliac crest autograft as the most typical choice for an interbody spacer. When allograft is used for ACDF without anterior plate fixation, successful fusion has been reported in 90% of single-level surgeries; however, in cases requiring two-level surgeries, the fusion rate decreases to 72% when allograft is used without supplemental plate fixation.10 Anterior cervical plate fixation significantly improves the successful arthrodesis after single-level ACDF. A 96% fusion rate has been reported when allograft is combined with anterior cervical plate fixation. In cases requiring two-level surgery, a 91% fusion rate has been reported when allograft is used in conjunction with anterior plate fixation.10 Drawbacks of some allograft interbody spacers include their limited supply, irregular dimensions, and the rare risk of transmitting infection (viral or bacterial). Recently, synthetic materials have been developed in an effort to overcome these limitations. Figure 2–4 Intraoperative photograph of a multilevel anterior cervical diskectomy with fusion utilizing poly-ether-ether-ketone spacers and an ATLANTIS VISION Anterior Cervical Plate System (Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN). Figure 2–5 Lateral x-ray of a multilevel anterior cervical diskectomy with fusion utilizing poly-ether-ether-ketone spacers and an ATLANTIS VISION Anterior Cervical Plate System (Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN). New synthetic spacers, such as poly-ether-ether-ketone (PEEK), are unlimited in supply, have regular dimensions, have similar modulus of elasticity to bone, are nonabsorbable, are radiolucent, and do not risk the transmission of infection from the donor (Figs. 2–4 and 2–5). When PEEK interbody spacers are combined with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) and anterior cervical plate fixation, a 100% successful fusion rate has been reported for ACDF.11 A study comparing surgical management (laminectomy alone) versus traditional conservative management was published by Matsunaga et al. They examined the natural history of patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis and lumbar stenosis for 10 to 18 years. Eighty-three percent of patients with neurological deficit or symptoms of neurogenic claudication refused nonsurgical treatment.12 The issue of whether to fuse a patient during a lumbar spine procedure typically occurs in the setting of lumbar stenosis requiring multilevel laminectomy. Few would argue that a fusion procedure would not be indicated in patients undergoing single-level laminectomy/hemilaminectomy for stenosis or disk space pathology. Surgical decompression without fusion of patients with lumbar stenosis is certainly well established. The permutations for the surgical treatment of lumbar stenosis with degenerative spondylolisthesis are many (laminectomy alone, laminectomy with posterolateral fusion, laminectomy with instrumented posterolateral fusion, transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF), posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF), anterior lumbar inter-body fusion (ALIF), etc.) (Figs. 2–6 and 2–7). Studies examining laminectomy without fusion date back to 1976 when Cauchoix et al reported on 26 patients undergoing laminectomy with or without facetectomy.13

Current Concepts in Spinal Fusion

versus Nonfusion

Decompression without Fusion—Cervical

Decompression without Fusion—Cervical

Decompression with Fusion—Cervical

Decompression with Fusion—Cervical

Decompression without Fusion—Lumbar

Decompression without Fusion—Lumbar

Laminectomy versus Laminectomy with Noninstrumented Posterolateral Fusion

Laminectomy versus Laminectomy with Noninstrumented Posterolateral Fusion

Should Posterior Lumbar Fusions be Instrumented?

Should Posterior Lumbar Fusions be Instrumented?

Decompression without Fusion—Cervical

Decompression with Fusion—Cervical

Decompression without Fusion—Lumbar

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Arthroplasty

Arthroplasty Conclusion

Conclusion