CHAPTER 17 Correction of Flatfoot Deformity in the Child

ARTHROEREISIS

Indications and Rationale

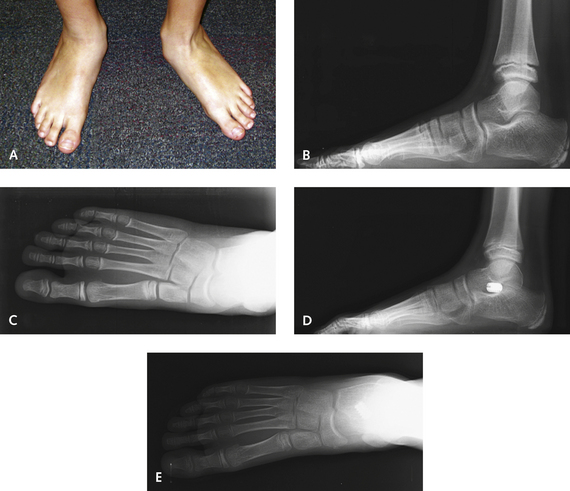

The goal of arthroereisis in the child is to properly orient the talus over the calcaneus; the joint is then allowed to remodel. This remodeling is expected to help prevent further problems later in life, such as degeneration or rigidity of the hindfoot. An arthroereisis implant can be considered to function as an internal orthotic device. This procedure has many advantages; most important, however, are the maintenance of motion it affords and the minimal associated morbidity. The indications for arthroereisis in the child are broad. Treatment results for children undergoing arthroereisis have been excellent, provided that the talonavicular joint is not significantly uncovered. The procedure seems to work very well in younger children who have predominantly heel valgus, presumably because they have more capacity for remodeling and adaptation of the forefoot (Figure 17-1). Once the talonavicular joint sags, particularly as seen on the lateral radiographic view, these feet seem to require more correction of the pronation deformity than a medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy can provide (Figure 17-2). If there is abduction deformity of the foot, with uncovering of the talonavicular joint, then neither the arthroereisis nor the medial displacement osteotomy is likely to be successful. In anecdotal reports, in the adult flatfoot, more of the talocalcaneal deformity is corrected with arthroereisis than with the abduction of the transverse tarsal joint. Most important, children are able to bear weight in a boot within days after the arthroereisis surgery.

Surgical Technique

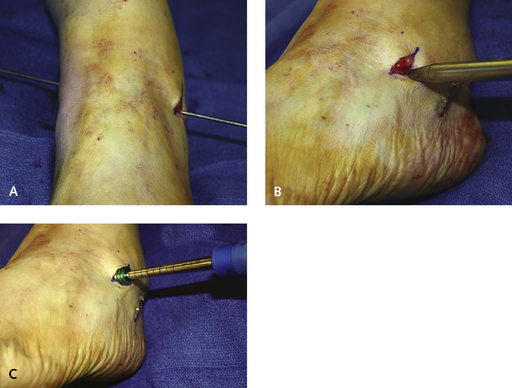

An incision is made in the sinus tarsi, approximately 1.5 cm in length. To locate the exact position for the incision, it is necessary to palpate the “soft spot” between the distal tip of the fibula and the anterior process of the calcaneus. The incision is placed inferior to the intermediate dorsal cutaneous branch of the superficial peroneal nerve and dorsal to the peroneal tendons. A guide pin that functions as a cannula for the arthroereisis dilators and sizers is inserted into the tarsal canal from lateral to medial, pushed through a puncture on the medial foot, and then clamped (Figure 17-3). The anatomy of the tarsal canal must be appreciated: The canal is shaped like an oblique cone and passes from anterolateral to posteromedial. The guide pin should therefore be inserted in the same plane as that of the tarsal canal and not directly medially. A slight resistance to the insertion of the pin can be felt as it traverses the interosseous ligament; then it is pushed through until it is protruding on the medial skin. The clamp on the guide pin prevents loss of position of the guide during repeated insertion of the sizers and trial implants.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree