CHAPTER 18 Correction of Flatfoot Deformity in the Adult

Nothing in foot and ankle surgery elicits controversy as much as the “appropriate” correction of flatfoot. To some extent, this controversy has a lot to do with the many satisfactory operations that are available for correction of similar deformities. Because of the plethora of these surgical alternatives, choosing a procedure can get confusing, and at times the surgeon needs to find an operation that works well and then stick with it. This decision does, of course, depend on the severity of the deformity, the appearance of the foot, and the flexibility of the hindfoot and forefoot. Perhaps the most important aspect of decision making is the presence of flexibility in the hindfoot. Specifically, is the subtalar joint completely correctable into a neutral position? If such reduction is possible, can it be achieved without associated significant forefoot supination? (Figure 18-1). The management approach also will differ for a unilateral deformity or that associated with flatfoot since childhood that has more recently become symptomatic, perhaps unilaterally (Figure 18-2). The approach to correction of deformity is based on the flexibility of the foot; the presence of rupture of the posterior tibial tendon, the spring ligament, or the deltoid ligament; and the presence of any arthritis or secondary deformity of the midfoot.

Figure 18-2 This is clearly a unilateral flatfoot deformity and in the adult is most likely due to a rupture of the posterior tibial tendon. Is the foot easily reducible? Where is the apex of the deformity? (See Figure 18-3.)

CLASSIFICATION OF THE FLATFOOT DEFORMITY

Stage I: Tenosynovitis Without Deformity

Stage II: Ruptured Partial Tibial Tendon and Flexible Flatfoot

Stage IV: Ankle Valgus

SURGICAL PROCEDURES FOR CORRECTION OF FLATFOOT

Tenosynovectomy

A tenosynovectomy is indicated in patients who have inflammatory changes in the PTT but do not have deformity. Usually tenosynovectomy is necessary early in the course of the disease process as the tendon is beginning to tear. In some patients, however, an inflammatory tenosynovitis may be associated with a seronegative spondyloarthropathy. I am more inclined to perform earlier surgery in these patients, because infiltrative tenosynovitis will eventually cause rupture of the tendon (Figure 18-5). A tenosynovectomy is indicated after failure of nonoperative care, whatever that happens to consist of. The nonoperative regimen generally consists of a period of immobilization in either a boot or a cast, followed by use of some sort of brace or orthosis. In addition, a decision has to be made whether to correct any (mild) deformity of the hindfoot along with the tenosynovectomy.

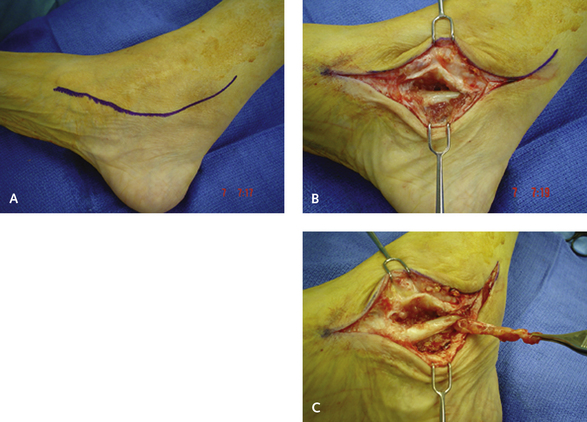

To begin the tenosynovectomy, an incision is made posteromedially along the length of the tendon, and the retinaculum is opened completely (Figure 18-6). Occasionally, the tenosynovitis is a result of a stricture or stenosis of the retinaculum immediately behind the medial malleolus. This stricture creates an hourglass shape to the tendon, with obvious deformity and inflammatory change visible in the tendon. Once the retinaculum has been opened, the tendon is inspected. The inflammatory change is not always that obvious and frequently is on the posterior surface of the tendon and tendon sheath. The tendon must then be rotated to inspect the posterior surface. I find that skin hooks are the easiest way to do this, by flipping the tendon around to inspect the posterior surface. The inflammatory tissue is then removed from the tendon sheath and the tendon itself; either dissection scissors or a knife blade is used in this procedure. Rubbing the tendon vigorously with a sponge also facilitates removal of this inflammatory tissue. Finally, the tendon should be inspected for any tears, which, as stated, usually are on the posterior surface (Figure 18-7). If a tear is identified, it is repaired with a running suture of monofilament absorbable suture. I use a 2-0 suture and bury the knot and then run the suture along the length of the tendon, imbricating the tendon along the way as the repair is performed. I do not repair the flexor retinaculum, because the tendon will not subluxate provided that the foot is immobilized for a few weeks after surgery. It is always a good idea to support the tendon if there is a tear, which is simultaneously repaired; in such instances, either an arthroereisis or a calcaneus osteotomy can be performed. Weight bearing can be started as tolerated in a boot, and gentle passive range-of-motion exercises can start after 2 weeks, followed by non–weight-bearing exercise, including swimming and cycling.

Medial Translational Osteotomy of the Calcaneus

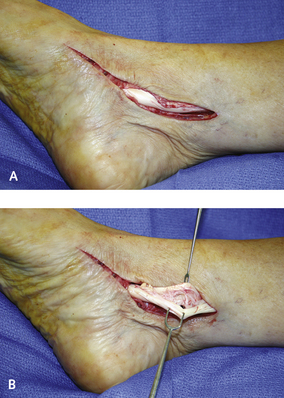

An incision is made two fingerbreadths below the tip of the fibula in line with the peroneal tendon (Figure 18-8). The incision is deepened into subcutaneous tissue, and immediately the sural nerve and lesser saphenous vein must be identified and retracted. A retractor is inserted into the tissue, and then once the nerve is retracted, the incision is deepened onto periosteum, which is reflected to expose the calcaneus. I try to perform the osteotomy as close as possible to the axis of the subtalar joint. After subperiosteal dissection, two curved soft tissue retractors are inserted on the dorsal and inferior aspect of the tuberosity. The inferior retractor is pushed between the calcaneus and the plantar fascia and serves as a retractor of the soft tissues during the osteotomy. The cut is made perpendicular to the axis of the tuberosity at a 45-degree angle with respect to the calcaneal pitch angle. An osteotome should not be used, because more control is afforded by the use of a wide saw blade. A punching action of the saw is used for the osteotomy, to permit the perforation through the medial aspect of the tuberosity to be felt. A smooth laminar spreader with no teeth is inserted into the osteotomy site to distract the calcaneus, and the medial periosteum is separated. The medial translation is then facilitated, but cephalic translation is avoided. Once the calcaneus is held in the desired position, which is approximately 10 to 12 mm of medial shift, it is fixed with one 6.5-mm cannulated screw introduced from inferolateral to anteromedial to enter the harder sustentacular bone. Compressing the overhanging lateral ledge of bone is important because presence of a ridge can cause irritation on the soft tissues and sural nerve. This is a stable osteotomy, and weight bearing can start after 10 days, either in a cast or in a boot, depending on the additional procedures performed.

Flexor Digitorum Longus Tendon Transfer

The indications for FDL tendon transfer are a flexible flatfoot and a reducible subtalar joint with or without forefoot supination. Obesity does not appear to be a contraindication to this procedure, and provided that the foot is flexible, the addition of a calcaneal osteotomy to the FDL tendon transfer will support the foot. Occasionally, if I am concerned about the ability of the tendon transfer and the osteotomy to support the foot completely, I may add a subtalar arthroereisis to support the subtalar joint. This is particularly helpful in patients who have an increase in the talar declination but have good coverage of the talonavicular joint (Figure 18-9).

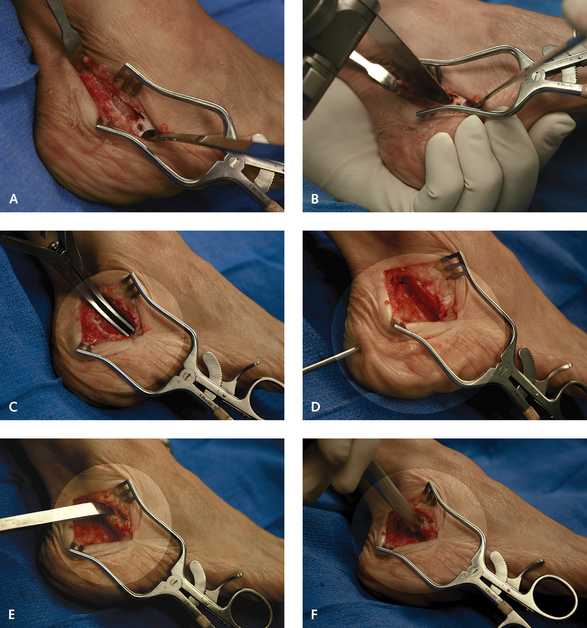

To begin the FDL tendon transfer, an incision is made medially starting behind the medial malleolus and extending distally toward the medial cuneiform. This incision is deepened to the flexor retinaculum, and the PTT sheath is opened. Frequently, the PTT rupture is partial and longitudinal, and it fissures in the posterior aspect of the tendon and is visible once the tendon is rotated and rolled backward. In addition to tears of the tendon, the entire capsule-ligament complex must be inspected for any defect, tear, or rupture that could involve the deltoid ligament, the talonavicular capsule, or the spring ligament. Each of these much be addressed in addition to the tendon transfer (Figures 18-10 to 18-14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree