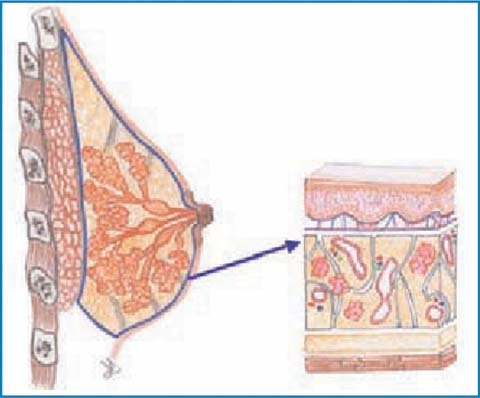

Fig. 5.1

Vascularization of the breast and nipple-areola complex

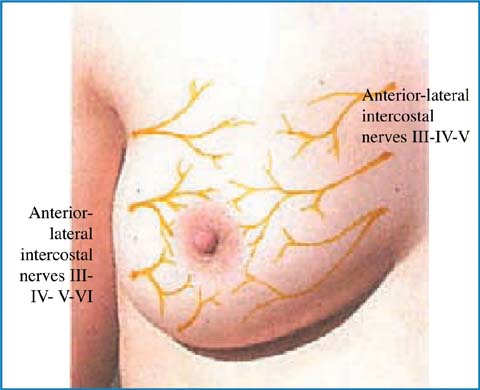

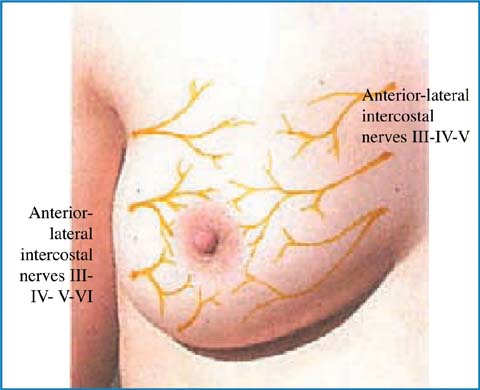

5.3.2 The Innervation of the Breast and Nipple-areolar Complex

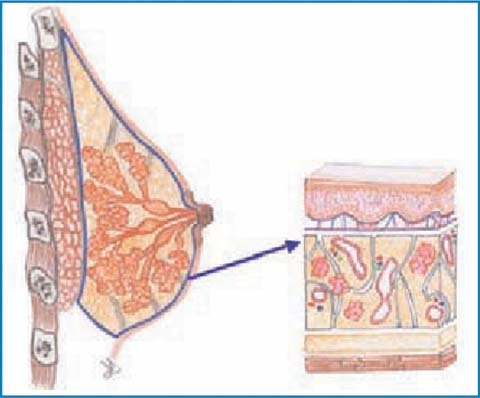

The innervation of the NAC is mainly supplied by the anterior-medial and anterior- lateral branches of the intercostal nerve IV. The intercostal nerves III and V, together with the supraclavicular nerves, contribute to sensitivity. The intercostal nerve IV enters laterally through the IV space and runs medially along the deep fascia and upwards to reach the NAC through the parenchyma. In the light of the fact that various nerves contribute to the innervation of this area, the surgical sectioning of some of these branches should not result in the anesthesia of the NAC. Also true is the fact that it is practically impossible to choose preferential incisional surgical options to conserve the nervous fiber section; such impossibility seems to be valid also for vascularization (Fig. 5.2).

Fig. 5.2

Innervation of the breast and nippleareola complex

Most authors reported that the sensitivity of the nipple after NSM reduces significantly and the same is valid for its erectile function [12], with a possibility of recovery, after about 6 months, in 28% of cases.

5.3.3 Planning the Surgery

1.

Evaluation of the surgical indications.

2.

Getting consent for the surgery. It is important to explain clearly some fundamental points: any oncologic risks, even if small, linked to the persistence of the NAC, as well as the surgical approach chosen and the expected cosmetic outcome, any possible complications (discoloration/ischemia/ necrosis of the NAC, the reduction-loss of nipple sensitivity and its erectile function, prosthesis infection) and problems linked to axillary lymph nodes.

3.

Choosing the surgical approach: which incision to be carried out taking into consideration any existing scars; which approach allows an easy and radical removal of all the gland tissue; which one allows the perfect identification and skeletonization of the retroareolar tissue and safeguards the vascular system of the NAC.

4.

Study of the axillary sentinel lymph node or the axillary lymph node dissection.

5.

Planning breast reconstruction (prosthesis, type and sizes, flaps, other).

5.3.4 Indications and Contraindications

The indications and the contraindications for NSM must be carefully evaluated before proposing and carrying out the operation. The follow-up of this new surgical approach is still too young to drive absolute criteria and the literature always presents new elements for reflection [12–15].

The criteria to select this surgery include both clinical and instrumental criteria (tumor size ≤ 3 cm, tumor distance from the NAC > 2 cm, the possibility of an MRI of the NAC, clinically negative axillary lymph nodes, absence of Paget’s disease and the absence of an inflammatory component), and also anatomical criteria (not big breast size, no high-grade ptosis). Oncologic and prophylactic indications are listed in Table 5.1 together with absolute contraindications.

Table 5.1

Indications (oncologic and prophylactic) and contraindications of NSM

Oncologic | Multifocal DCIS |

Multifocal and multicentric T1, T2 | |

T1 with extensive intraductal component (EIC) | |

Margins involvement after conservative surgery | |

High tumor/breast ratio | |

Relapse post QUART | |

Patient refuses BCT | |

Patient’s refusal or impossibility to radiotherapy | |

Difficulty for follow-up after conservative surgery | |

Prophylactic | BRCA1/BRCA2 (risk reduction 81–96%) |

Opposite breast | |

LCIS | |

ADH? | |

Papillomatosis? | |

Phyllodes tumor? | |

Contraindications | Tumor distance < 2 from NAC in mammography or RM studies |

Nipple retraction | |

Subareolar microcalcifications | |

Bleeding from the nipple | |

Skin involvement | |

T3, T4 | |

Inflammatory disease | |

Paget’s disease | |

N+ ? | |

Distance from the nipple to the inframammary fold > 8 cm | |

Large breast ( > 400 cm3) | |

Intraoperative histological involvement of retroareolar tissues |

Literature on these indications is in sufficient agreement. Many studies have shown that the SSM, have the same results as the modified radical mastectomy in terms of local recurrences, both when treating infiltrating tumors and intraductal ones [16–18]. A very debated issue is the oncologic risk linked to the maintenance of the NAC. In a literature review published in 2001, Cense [19] claimed that the percentage of neoplastic involvement of the NAC in mastectomies varies from 5.6 to 58%, and has a significant correlation with the tumor size and its distance from the nipple [16, 20]. In fact, in tumors larger than 4 cm (T3), there are neoplastic cells within the NAC in more than 50% of the cases. The same applies if the mass is less than 2 cm away from the NAC. In 2001, a retrospective analysis of 217 cases by Simmons and Brennant [21] found the involvement of the NAC in 10.6% of the cases. This percentage drops to 6.7% of peripheral tumors, with a diameter of less than 2 cm and with less than two positive lymph nodes. Analyzing the involvement of the areola and the nipple separately, the authors sustain that the areola is implicated in only 0.9% of the cases of NAC involvement. In the rest of cases, the tumor is restricted to the nipple. This fact favors the maintenance of the areola (areolasparing mastectomy), when the conservation of the nipple is not possible [22–28]. In fact, the lymphatic drainage of the breast is not, as Sappey [29] claimed, toward the nipple, but toward the deep lymphatic prepectoral lymphatic plexus [30]. In addition, Welligs [31] has shown that the anatomical area of the breast where tumors form, is the terminal duct lobular unit (TDLU), which is present only at the base of the nipple and not at the tip. Therefore, only the outer surface (the skin) of the nipple remains when the core is removed together with all the glandular tissue [32–35]. The risk of the nipple involvement, therefore, seems to directly correlate to the tumor size and the distance of the tumor from the nipple. It is necessary to reconsider the importance of positive lymph nodes, the presence of lymphatic vascular invasion (LVI) as well as the extensive intraductal component (EIC). The risk factors linked to local recurrence seem to be different; in the case of infiltrating tumors one should consider the grading, the overexpression/amplification of the HER2/neu and the molecular characteristics of the tumor (luminal B). It seems that in situ tumors correlate with the patient’s age (< 45 years), absence of estrogen receptors, grading, overexpression of HER2/neu and high value of Ki67. The preoperative histological examination might represent the best solution to define the histological, hormonal and biological characteristics of the tumor so as to reduce local recurrence, selecting the patients who should undergo a NSM [36]. Intraductal mammary carcinoma and infiltrating ductal carcinoma with important in situ components, negative hormone receptors and high degree overexpression of HER2/neu, are all associated with a high risk of local recurrence that can manifest itself as Paget’s disease of the nipple [37]. For this reason, it is absolutely necessary to inform the patient of the existing problems and to obtain a truly informed consent.

5.3.5 The Surgical Technique

The NSM, like other conservative mastectomy techniques, involves the removal of the entire mammary gland while sparing the cutaneous envelope. The element that characterizes the operation is the conservation of the NAC, after an intraoperative histological exam of the retroareolar tissue.

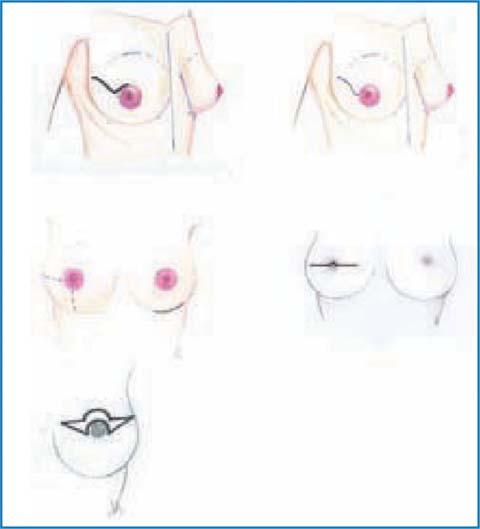

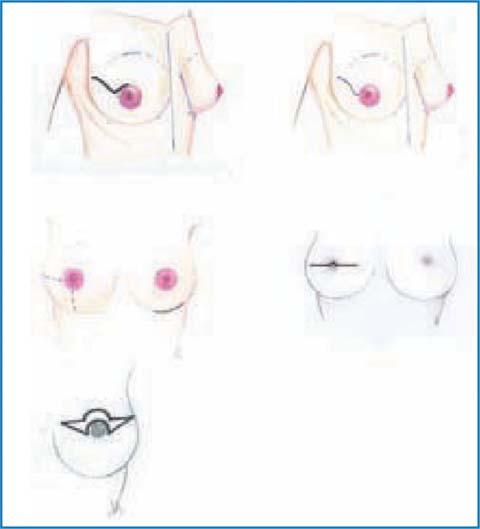

5.3.5.1 Skin Incisions

Several skin incisions (Fig. 5.3) have been proposed and they can be summarized as follows:

Upper periareolar

Upper periareolar with lateral extension

Transareolar — transnipple

Inframammary /inferior lateral

Upper-outer radial

Omega (mastopexy).

Fig. 5.3

Skin incisions

An upper-outer radial incision should be given preference, due to its various advantages: excellent scar outcome; easier access to the axilla, the nipple and the complete glandular demolition; the highest possibility of conserving the areolar vascularization, and the best reconstruction time, both in small and large breasts. All the periareolar incisions have the advantage of resulting in an almost invisible scar. Therefore, besides allowing excellent access to the retroareolar region, they also favor the subareolar resectioning timing; they are the preferred choice for small-sized breasts, due to the difficulties to reach the inframammary fold medially and the neurovascular elements of the axilla (if lymphadenectomy is mandatory).

The periareolar incision with lateral extension certainly ensures wider access to axilla; however, it often results in a deviation and lateralization of the NAC, requiring corrective action. The external inframammary incision has the advantage of a hidden scar but, on the other hand, it creates a few problems as far as the demolition of the upper or middle quadrants is concerned and in reaching the axilla, especially in large breasts.

The dissection occurs along the superficial fascia, taking care to respect the skin flap vascularization; most vessels flow deeply in the muscle band, but there might be perforated vessels to the skin that must be coagulated (Fig. 5.4). The thickness of the flaps must be kept constant throughout their extension. To reach this aim, the skin must be stretched upwards by the second surgeon and the gland in the opposite direction by the surgeon.

Fig. 5.4

Dissection of the glandular plane

Both these maneuvers facilitate the identification of the correct dissection plane, which should be in the subcutaneous tissue, immediately at the surface of the fascia, which is above the mammary gland.

From time to time, during the dissection, the skin flap must be palpated to ensure a uniform and adequate thickness, not too thin and devascularized (necrosis!!), and not too thick as there would be a risk of glandular residue (local recurrence!!). In order to assess the vitality of the flaps and the NAC, studies have evaluated perfusion with the fluorescence emitted after an infusion with indocyanine green dye [38].

The flap thickness may depend on the patient’s characteristics; in slim patients, it may be only a few millimeters thick (2–3 mm) and transparent to light, while for obese patients, it can be up to 1 cm. In all cases, the removal of glandular tissue must be truly radical. The releasing of the gland from adipose tissue begins from the upper quadrants getting to the pectoralis muscle up to its infraclavicular bundles of the pectoral muscle. Medially, the muscle fascia is not well-defined and the dissection leads to the parasternal line, where the perforating vessels coming from the internal mammary artery are present; on the lower side, the muscle is followed up to the joint with the posterior membrane, where the skin adheres to the chest wall at the inframammary fold. The anterior axillary pillar, the margin of the pectoralis major and the lower anterior serratus can be reached laterally. The dissection must be carried out carefully with meticulous technique to prevent ischemia of the skin flap. Proceeding from the top toward the bottom, the gland is mobilized from the deep plane, incising and dissecting the pectoralis major muscle band.

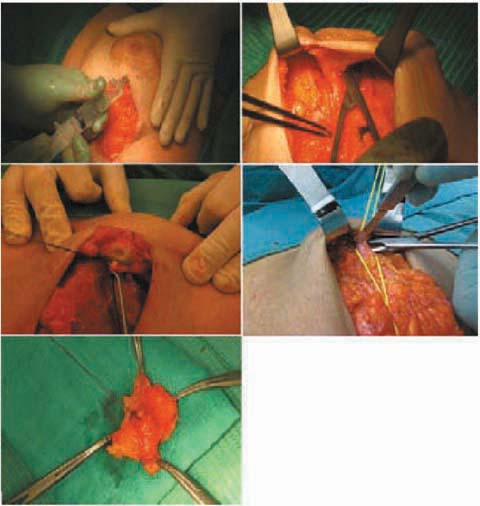

5.3.5.2 Treatment of the Subareolar Tissue

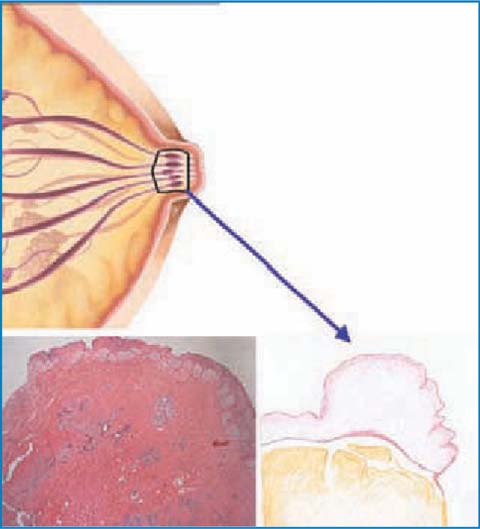

The most characteristic element of this surgery is the conservation of the NAC. For this purpose, as mentioned above, it is mandatory to carry out an intraoperative histological study of the margin of a section of the subareolar tissue. During the glandular dissection, one should proceed with meticulous care when isolating the areolar conus, which is followed and sectioned until removal from within the nipple (avoiding the use of electrosurgery to avoid artifacts from electrocautery). This sectioning, which reaches the dermis plane, almost transforms the NAC into a sort of dermoepidermal graft, easily revascularized from the underlying muscle tissue. This timing is greatly facilitated by the hydrodissection technique, which consists of infiltrating the retroareaolar tissue with an epinephrine and saline solution, to allow the identification of an anatomical and bloodless incision plane [39] (Fig. 5.5). This technical procedure makes the surgical procedure easier, quicker and probably even safer from an oncologic point of view since a subdermal plane, which allows a better and complete removal of the retroareolar breast tissue, is obtained. The resected retroareolar tissue is then sent for intraoperative histological examination, subjected to the right orientation. The pathologist then prepares at least three frozen sections at 200–300 microns; a negative or positive result for tumor presence is given. When positive, he specifies the presence of infiltrating or in situ tumor, extension and distance from the edge of nipple (Fig. 5.6). At this point, our choices can be: conserve the nipple, removal of the NAC or, given the rarity of areolar accessory ducts, removal of the nipple alone; this latter variant of the technique (areola-sparing mastectomy), which is sometimes used, involves the closure of the circular areolar wound with a purse-string suture, creating a scar that is almost punctiform with projection and a fairly good esthetic result. The result of the definitive histological test must be considered with great attention, since the possibility of false negatives from the intraoperative histological test seems to be approximately 4.6% [40–45]. In all cases in which a nipple-sparing mastectomy is carried out for oncologic purposes, even for the treatment of noninfiltrating forms, it is advisable to check the state of the axilla (sentinel node biopsy/axillary dissection).

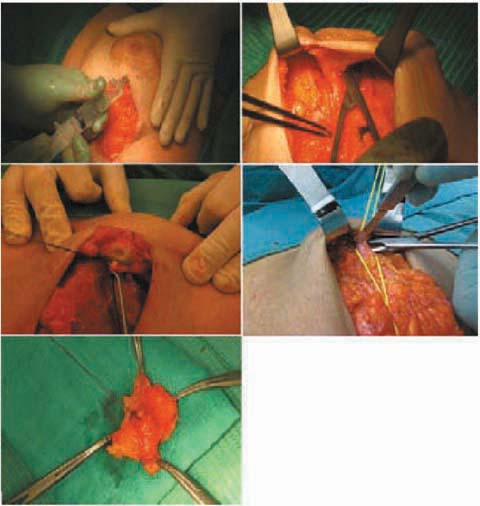

Fig. 5.5

Dissection of the subareolar tissue

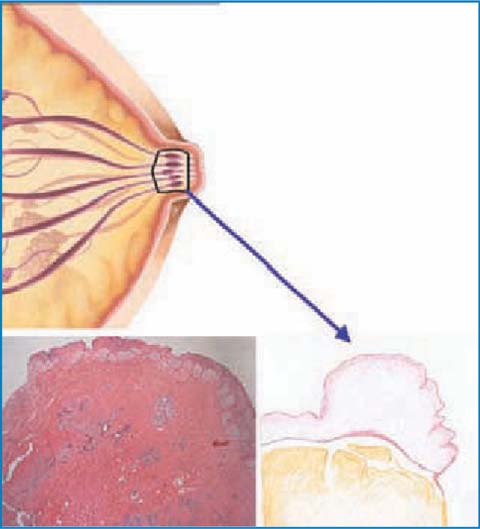

Fig. 5.6

Intraoperative study of the subareolar tissue

5.3.5.3 Reconstruction Time

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree