CHAPTER 39 Component Removal

Acetabulum

KEY POINTS

Preoperative planning based on knowledge of the existing implant and any relevant equipment requirements is essential.

Preoperative planning based on knowledge of the existing implant and any relevant equipment requirements is essential.As the components and techniques for acetabular reconstruction continue to advance, so do the techniques for acetabular component removal. Historically, removing grossly loose cemented acetabular components was not technically difficult, as long as exposure was adequate. However, removal of well-fixed cemented and, particularly, cementless components has remained a challenge, often leading to significant bone destruction and compromised attempts at subsequent reconstruction. The decision-making process with regard to when to remove an acetabular component versus leaving a stable construct in place has also evolved over recent years.1–3 This evolution has occurred in response to the difficulty of removing a well-fixed implant, especially one associated with large osteolytic defects, in which the surrounding bone is already in a compromised state. Undoubtedly, acetabular components have been left in place under less than desirable conditions at the time of revision surgery because of the perceived difficulty associated with component removal and subsequent reconstruction. This underscores our need for safe and reliable acetabular component removal techniques to improve patient outcomes.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

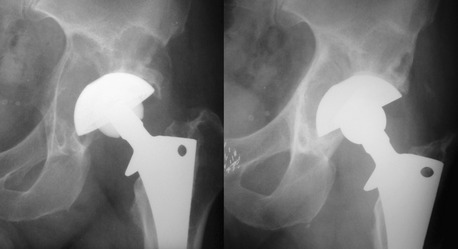

Isolated acetabular insert exchange may be carried out in select situations involving modular acetabular components. The same indications for retaining a well-fixed acetabular component must be met, and compatible inserts should be available. This requires a preoperative knowledge of the type of implant being revised, whether the modular inserts in question are available, and specifics about the locking mechanism involved. Clinical results have been encouraging, even when procedures are associated with osteolytic lesions (Fig. 39-1).2,4 If a locking mechanism has been damaged or a corresponding acetabular insert is unavailable, a compatible insert may be cemented into an existing well-fixed acetabular shell.5–7 These constructs have shown initial promising results, but their durability over time has not been proven. Isolated acetabular insert exchange may halt progressive osteolytic changes, allow for subtle changes in position and stability, and provide the ability to take advantage of newer bearing materials. Although seemingly simple to carry out, insert exchange has been associated with significant complications, particularly postoperative instability.8

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

A typical workup in planning a revision hip procedure will focus on determining the source of the failure. Obviously, infection requires component removal, and ascertaining its presence to the best of one’s ability should be performed before surgery. No test for infection is conclusive, but negative sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and isotope scans are typically predictive of absence of infection. Loosening is another indication for acetabular revision and may be determined by careful scrutiny of serial radiographs. Component migration, complete radiolucent lines in all three zones, radiolucent lines 2 mm or greater in any zone, radiolucent lines that initially appear after 2 years, and progression of radiolucent lines after 2 years all correlate with acetabular component loosening.9

Exposure may be selected based on surgeon’s comfort and expertise; however, all acetabular revisions require circumferential exposure of the entire periphery of the acetabular component. In addition to the planned component removal, plans for the proposed reconstruction must also be taken into account, especially with regard to potential structural bone grafting. Lateral exposure to the hip has been associated with a lower rate of instability after acetabular revision4; however, the posterior approach is more extensile and may be converted into an extended trochanteric osteotomy if necessary. If the femoral component is to be revised, its removal should be completed early in the surgery to allow better access to the acetabulum. Cement in the femoral canal may be left in place if indicated after the femoral removal reinsertion technique described by Nabors and colleagues10 or removed after acetabular revision to minimize blood loss. If the femoral component is left in place, the modular head should be removed if possible, and sufficient exposure obtained to mobilize the femur clear of the acetabulum.

With the posterior approach, the anterior capsular attachment on the femur should be released or excised, leaving enough capsular tissue for repair posteriorly. This may be tedious and difficult to accomplish anteriorly if the femoral component is left intact but is critical to gaining adequate exposure. The extensive nature of this release with a retained femoral component may contribute to the high rate of instability after isolated acetabular revision.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree