CHAPTER 19 Complications of Treatment of Flatfoot

HOW TO MANAGE THE FAILED TENDON TRANSFER

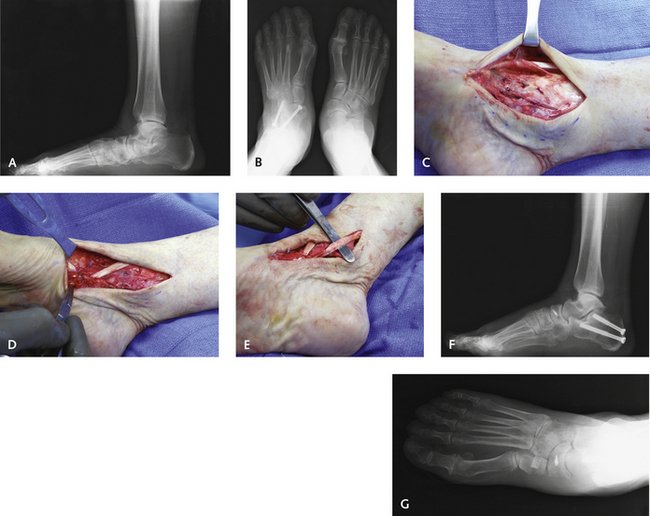

Figure 19-1 presents an example of failure of a previous flexor digitorum longus (FDL) tendon transfer. The patient was a 54-year-old active woman weighing 76 kg. The hindfoot was quite flexible, and with the heel reduced to neutral there was a fixed forefoot supination deformity of 20 degrees. No active inversion was noted, and pain was present along the medial border of the foot and ankle, in addition to sinus tarsi pain, the result of subfibular impingement. Traditionally, if the FDL has already been used in a tendon transfer, little is left to function as an invertor. The lateral side of the foot can be weakened with a peroneus brevis-to-longus transfer, which would have the added benefit of plantar-flexing the first ray. The lateral radiograph (see Figure 19-1, A) shows a break in the foot at both the talonavicular (TN) and naviculocuneiform (NC) joints. Certainly a fusion of the NC joint could be added to the procedure without loss of too much function, but this procedure would not address the weakness and lateral foot pain. The patient had already undergone a successful triple arthrodesis on the opposite foot for management of a very rigid flatfoot deformity and wanted to avoid another arthrodesis. In this patient, uncovering of the TN joint was not so extensive as to necessitate a lengthening of the lateral column, whether by osteotomy or by arthrodesis. I do not like to use a subtalar implant in the adult, and although this would be a reasonable indication, this procedure still does not address the muscle imbalance. I therefore selected the anterior tibial tendon (ATT) for transfer, modifying the original Young procedure.

For this modified procedure, the navicular is exposed, and a thick osteoperiosteal flap is raised from the center of the navicular and retracted inferiorly (see Figure 19-1, C). This flap can include the remnant of the posterior tibial tendon (PTT) as well. A ridge with an overhang of approximately 5 mm is then prepared under the navicular with a curette or chisel, to function as a ledge for the transferred ATT. The retinaculum of the ATT is opened and released proximal to the ankle joint under direct vision. The ATT is then pulled below the navicular into the prepared slot (see Figure 19-1, D) and sutured either using the osteoperiosteal flap or by adding a suture anchor into the body of the navicular. If an anchor is used, fluoroscopic guidance is recommended to ensure that it is in the navicular and not protruding into the joint. The remnant of the PTT can now be cut, sacrificed, or repaired, depending on the status of the tendon (see Figure 19-1, E). In this patient, after these procedures there was slightly more forefoot supination than I would accept, and plantar flexion of the medial column was obtained with an opening wedge osteotomy of the medial cuneiform. The postoperative radiographs showed excellent restoration of the height of the arch of the foot, as well as coverage of the TN joint (see Figure 19-1, F and G).

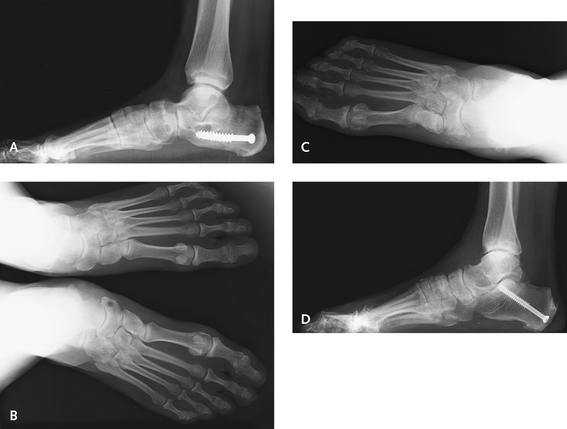

A similar example of the same problem is shown in Figure 19-2. The patient was a 61-year-old man who had been treated with a previous calcaneus osteotomy and a transfer of the flexor hallucis longus. The hindfoot was quite flexible, and the heel was in moderate valgus. On observation of the heel from posterior, the calcaneus osteotomy did not appear to have accomplished much. The elements of surgical decision making were similar to those in the case shown in Figure 19-1, in which an arthrodesis was an option; however, maintaining flexibility seemed preferable in that very active patient. The ATT was transferred under the navicular, and the calcaneus osteotomy was repeated. It was not necessary to include an osteotomy of the medial cuneiform. An important point is that the ATT is not detached from its insertion and is levered inferiorly under a prepared osteoperiosteal flap in the edge of the navicular. The extent of bone resected in this process can be appreciated on the anteroposterior radiographic view (see Figure 19-2, C), in which the medial pole of the navicular has been removed to create the ridge under which to attach the ATT. It is important to leave no sharp edges on the ridge on the proximal navicular, because consequent damage to the ATT can lead to its rupture—a complication that has occurred in one of my own patients. When the rupture occurred, the patient noticed a sudden change in the foot at 8 weeks after surgery, and the ATT was no longer palpable dorsomedially. The rupture was repaired by reattaching the ATT to the dorsal central aspect of the navicular using a suture anchor.

Although errors in decision making and technique are inevitable, some of these are entirely avoidable. In the case illustrated in Figure 19-3, a 47-year-old woman was treated with a transfer of the FDL for correction of a flatfoot deformity. At 9 months after the surgery she presented with considerable pain in the anterior ankle, and on an anteroposterior radiograph of the foot, marked loss of the TN joint space was readily apparent. The diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis was confirmed with a positive rheumatoid factor titer, and a TN arthrodesis was used for correction.

A simple error in technique is illustrated in Figure 19-4: In the case depicted, an opening wedge osteotomy was performed in conjunction with a transfer of the FDL tendon and a calcaneus osteotomy. The incorrect insertion of the bone wedge into the cuneiform, which fractured into the first metatarsocuneiform (MC) joint (see Figure 19-4), is evident. This technical error can be avoided by inserting a guide pin in the cuneiform from dorsal to plantar and obtaining a lateral view radiograph to ensure the correct orientation of the osteotomy. The cuneiform inclines obliquely, and the osteotomy is not perpendicular to the axis of the foot but must be oriented to the axis of the cuneiform. The osteotomy cut also must be completed with the saw and not end in the cuneiform, because use of an osteotome to complete the cut may result in fracture extending out into the MC joint, which probably happened in this case. Although arthritis did not develop in this patient over 3 years of follow-up, the potential for this complication nonetheless remains worrisome. The “hump” evident in the midfoot was the result of the incorrect axis of the osteotomy, which unfortunately caused abutment and symptoms in shoes.

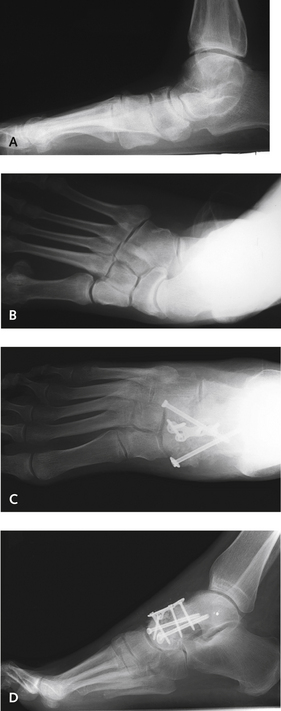

What is the optimal approach totreatment of the extremely flexible flatfoot? Is it always possible to avoid arthrodesis? In Figure 19-5, illustrating the case of a 44-year-old man with a unilateral flexible flatfoot, significant uncovering of the TN joint is apparent. The lateral radiographic view showed quite a lot of sag at the TN joint as well, with a fairly marked alteration in the talocalcaneal angle. In such cases, I have found that despite addition of a lateral column–lengthening procedure, instability may persist at the TN joint, increasing the likelihood of subsequent failure. Accordingly, although it is therefore always preferable to perform a tendon transfer with osteotomies, a TN arthrodesis is a good, reliable procedure and was performed in this patient with a successful result. The postoperative improvement in the talocalcaneal angle can be readily appreciated on the lateral view, even on a non–weight-bearing radiograph (see Figure 19-5, D).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree