Definition and Incidence

Definition and Incidence

Complications of rhinoplasty have been estimated at 6 to 15%, with between 5 and 10% of primary cases requiring revision.1 Complications can be considered as functional, aesthetic, or a combination of the two.

Functional complications of rhinoplasty generally involve postoperative impairment of nasal airflow. They are fairly straightforward to identify, because they are associated with specific symptoms and signs. In a retrospective series of 500 open rhinoplasties, postoperative degradation in nasal airflow occurred in 0.8% of cases.2

Aesthetic complications of rhinoplasty are harder to define. A primary difficulty in considering aesthetic complications of rhinoplasty derives from the subjective nature of beauty. Patients and surgeons may experience the postoperative result differently. Our experience has been that the surgeon is often more critical than the patient in judging surgical outcomes.

Most studies report patient satisfaction after rhinoplasty to be greater than 90%. However, there are no widely accepted validated instruments for patient satisfaction in aesthetic surgery; therefore, definitive measures of patient satisfaction are not available.3

Ideal proportions have been defined for nasal structure, but recognized variations exist across ethnic groups.4 Nevertheless, no nose exactly replicates ideal proportions, and given the importance of harmonizing nasal structure within the greater face, not every nose should be proportioned the same. Therefore, even though validated instruments based on objective ideal proportions have been developed for measuring rhinoplasty outcomes,5 the utility of these instruments is unclear.

Classification of Complications

Classification of Complications

Complications of rhinoplasty can be classified in many ways. For the purpose of this review, we divided complications into the following four categories: (1) perioperative, (2) anatomic, (3) functional, and (4) psychological.

Perioperative Complications

Perioperative Complications

Bleeding

Persistent bleeding is the most common complication of rhinoplasty. Bleeding often occurs at the site of osteotomy. It is unclear whether the incidence of bleeding after rhinoplasty increases with concomitant septoplasty. Increased incidence of postoperative bleeding often has been associated with coagulopathies as well as the use of aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, such as ibuprofen.6 Concomitant turbinate surgery may also be associated with increased epistaxis in the postoperative period.

Trauma

After rhinoplasty, the nose is highly sensitive to trauma, particularly after osteotomies or significant septal work. Osteotomized nasal bones heal by fibrous union, not osteoneogenesis, because they are not under dynamic stress; therefore, the postrhinoplasty nose is more susceptible to trauma than the unoperated nose.

The first 2 weeks after surgery carry the highest risk from trauma. By postoperative day 5 to 7, fibrous healing usually makes the nasal bones resistant to displacement. By 14 days, sufficient collagen matrix forms to fix the bones in place.

After trauma, grafts require special attention. Significant trauma to an alloplastic graft may require removal of the graft, especially if the graft itself is exposed. Autogenous grafts, such as bone, can often be salvaged in the setting of posttraumatic edema with warm compresses, elevation, and prophylactic antibiotics.7

Other reported traumatic complications of rhinoplasty include anosmia, epiphora (lacrimal duct injury), blindness, iatrogenic arteriovenous malformations, devitalized tooth roots, and intracranial injuries.6

Infection

Infectious complications include cellulitis, septicemia, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and brain abscess. Considering that the area is (1) colonized by Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species, (2) impractical to sterilize, and (3) located in the danger zone of the face, rhinoplasty carries a high theoretical potential for infectious complications. Given their high rate of infection, alloplastic implants are generally avoided at the nasal tip and dorsum. Nevertheless, the rate of infection from rhinoplasty is typically for less than 3%.7

Figure 3–1 Nasal cellulitis/abscess.

Controversy exists regarding the use of prophylactic antibiotics. In general, prophylactic antibiotics are recommended with active infection at the surgical site, nasal packing greater than 24 hours, hematoma, or alloplastic implants.7

The most common pathogens after rhinoplasty include Staphylococcus, Pneumococcus, and Haemophilus influenza. Infections with Pseudomonas and Actinomyces have also been reported. Infections generally respond to antibiotic treatment and, when necessary, drainage. Although the nose lies within the danger area of the face, central nervous system infection is very rare. Toxic shock syndrome from nasal packing is reported at a rate of 16.5 per 100,000 (Fig. 3–1).6

Excessive Edema

Postoperative edema is a common sequela of rhinoplasty, particularly in patients with a thick skin–soft tissue envelope. Edema can last for up to 1 year after surgery. Preoperative steroids have been shown to decrease edema after rhinoplasty.8 Postoperative subcutaneous steroid injections also can help with edema in the supratip area.

Necrosis

Necrotic complications of rhinoplasty include septal perforation, saddle-nose deformity, skin necrosis, and cartilage breakdown. Smokers and patients with collagen-vascular diseases, such as scleroderma and any of the vasculitides, are predisposed to necrosis. Septal perforation is the most common necrotic complication after rhinoplasty and generally results from either opposing tears in the mucoperichondrium or from unrecognized septal hematomas.7 On rare occasions the nasal skin can necrose (Fig. 3–2). This usually occurs secondary to technical error during surgery, but it may associated with diabetes, smoking, or other forms of microvascular diseases.

Anatomic Complications

Anatomic Complications

The nose can be divided into thirds. The nasal tip defines the lower third of the nose. From a nasal subunit perspective, the lower third contains the soft tissue triangles, columella, lobule, and alae. The framework of the lower third of the nose includes the lower lateral cartilages, caudal septum, and nasal spine. The middle third of the nose contains the lower portion of the dorsal and nasal sidewall subunits. The upper lateral cartilages and dorsal septum form the framework of the middle third of the nose. The upper third of the nose consists of the upper portion of the dorsal and nasal sidewall subunits overlying the nasal bones. The framework of the upper third of the nose includes the nasal bones and their connections to the septum, frontal bone, and maxilla.

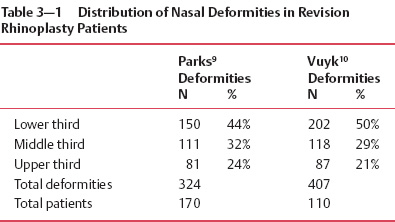

The lower third of the nose is the most frequent site of deformity after primary rhinoplasty. The upper third of the nose is the least common site of complication after primary rhinoplasty. Table 3–1 lists the distribution of deformities encountered in revision rhinoplasty patients from two studies.

Some surgeons divide complications of primary rhinoplasty into major and minor deformities. The most common major aesthetic deformities after primary rhinoplasty are, in order of decreasing frequency, pollybeak, saddle nose, middle vault asymmetry, and retracted columella. The most common minor complications are bossae and irregular dorsum. Table 3–2 lists these common complications.

Figure 3–2 Necrotic tip skin.

Tip

Projection

Projection of the nasal tip is a function of tip support mechanisms (Table 3–3). Major tip support mechanisms consist of the lower lateral cartilages (LLC), medial crural footplate attachment to caudal septum, and the scroll area [attachment of the LLC to the upper lateral cartilages (ULC)]. Minor tip support mechanisms include the following: (1) interdomal ligament, (2) dorsal septum, (3) attachment of the LLC to the sesamoid complex/pyriform aperture, (4) attachment of the LLC to the overlying skin-soft tissue envelope, (5) nasal spine, and (6) membranous septum. Modification of these support mechanisms affects nasal projection (Table 3–3).

| Kamer11 | Vuyk10 | |

| Major deformities | ||

| Pollybeak | 56% | 40% |

| Saddle nose | 16% | 21% |

| Middle vault asymmetry | 19% | 15% |

| Retracted columella | 9% | 11% |

| Minor deformities | ||

| Bossae | 22% | NA |

| Hanging columella | 13% | NA |

| Wide nasal base | 8% | NA |

| Underrotation | 4% | NA |

| Irregular or high nasal dorsum | 17% | NA |

| Total patients | 126 | 110 |

| Major Tip Support Mechanisms | Minor Tip Support Mechanisms |

|

|

Overprojection

True overprojection is a rare complication of rhinoplasty. More often, unrecognized overprojection persists after primary surgery. Failure to recognize overprojection distinguishes inexperienced rhinoplasty surgeons from experienced rhinoplasty surgeons. Apparent overprojection also may result from overreduction of the nasal dorsum.12 Correcting overprojection can be technically challenging and often requires shortening of overlong medial and lateral crura. After deprojection of the nasal tip, alar base reduction may be required to reduce alar flare (Fig. 3–3).13

Underprojection

In contrast to overprojection, underprojection is a frequent complication of rhinoplasty. Underprojection of the nasal tip results from disruption of nasal support. Causes of underprojection include the following: (1) overresection of the anterior septum, (2) overresection of the lower lateral cartilages, (3) disruption of the intercrural ligament and the soft tissue between the LLC and septum, and (4) scar contracture along the caudal septum from transfixion (hemi or complete) incisions.11

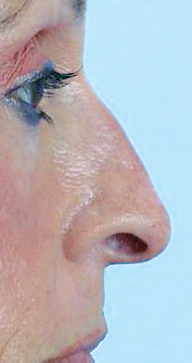

Underprojection may persist after primary rhinoplasty. Non-Caucasian noses, particularly Asian and African noses, are associated with underprojection (Fig. 3–4).13

Rotation

Rotation relates to the tripod structure of the nasal tip. The medial crura and caudal septum form one leg of the tripod while the lateral crura form the other two legs. Overrotation implies an overly obtuse nasolabial angle, and underrotation denotes an overly acute nasolabial angle (Fig. 3–5).

Figure 3–3 Overprojected nasal tip.

Overrotation

Overrotation of the nose may result from any maneuver that shortens the lateral crura or lengthens the central portion of the nasal tripod. Shortening of the lateral crural component of the tripod is associated with vertical dome division, lateral crural flaps, and excessive cephalic trim of the LLC. Lengthening of the central component of the nasal tripod causing overrotation generally occurs from overcorrection of the underrotated nose and may result from confusing underprojection with underrotation. Excessive resection of the caudal septum also may cause overrotation by cephalically rotating the medial crura.12–14

Underrotation

Underrotation (ptotic tip) after rhinoplasty is often caused by disruption in the medial component of the nasal tripod (caudal septum and medial crura). Underrotation is associated with inadequate length of the medial crura, loss of caudal septal or columellar support, scar contracture of the membranous septum, separation at the scroll region, and disruption of the medial crural attachments to the caudal septum.

Dynamic underrotation is caused by exaggerated function of the depressor septi nasi muscle. Dynamic underrotation can be identified preoperatively by observing tip rotation while the patient smiles or talks. Severing the attachments of the muscle to the membranous septum and medial crura via a transfixion incision will correct dynamic underrotation.14

Persistent underrotation occurs if primary rhinoplasty fails to correct unrecognized tip ptosis. Causes of underrotation in this setting include overly long lateral crura, short or weak medial crura, and an excessively long caudal septum.13

Figure 3–4 Poor tip projection.

Bulbous or Wide Tip

A bulbous (or wide) tip often results from failure to recognize a thick skin–soft tissue envelope. Domal modification without adequate projection into the overlying soft tissues creates a potential space for the accumulation of postoperative wound fluid and subsequent fibrosis.

Patients with thick skin–soft tissue envelope generally require a more projected, larger nose that sufficiently supports the nasal soft tissues.14 Postoperative edema may obscure the full extent of an amorphous tip. In patients with thick soft tissues, massage, taping, and subcutaneous triamcinolone injections may reduce the propensity for developing a bulbous or amorphous tip.13

Figure 3–5 Overrotated nose.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree