, Madan Ethunandan2 and Tian Ee Seah3

(1)

Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Poole, Dorset, UK

(2)

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University Hospital Southampton NHS Trust Southampton General Hospital, Southampton, UK

(3)

Orange Aesthetics and Oral Maxillofacial Surgery, Singapore, Singapore

Subunits and Anatomical Considerations

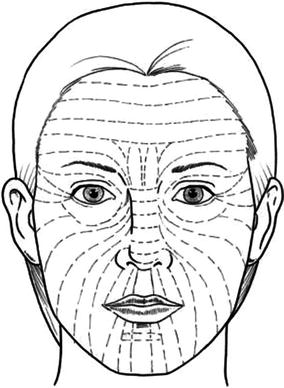

The cheek is the largest aesthetic unit in the face. It has an undulating contour and is defined by the nasofacial, melolabial and mentolabial folds medially, the infraorbital rim and zygomatic arch superiorly, the pinna and angle of the mandible posteriorly and the lower border of the mandible inferiorly. It can be divided into medial, buccal, infraorbital, zygomatic, lateral and mandibular subunits (Fig. 10.1).

Fig. 10.1

Cheek subunits

The medial subunit consists of skin adjacent to the nasofacial, melolabial and mentolabial folds. The buccal subunit encompasses the central cheek area lateral to the medial unit. The infraorbital unit represents the area below the lower eyelid. The lateral subunit is the area adjacent to the pinna and angle of the mandible. The zygomatic subunit is between the buccal, infraorbital unit and temple and overlies the zygomatic prominence. The mandibular subunit encompasses the area overlying the body of the mandible.

The facial artery and vein course the cheek unit obliquely from the lower border of the mandible, just anterior to the insertion of the masseter muscle up to the medial canthus region. They lie deep to the muscles of facial expression. The branches of the facial nerve emerge from the anterior border of the parotid gland and supply the muscles of facial expression and lie on their deep surface. The nerve is relatively unprotected in the cheek and mandibular subunits. The infraorbital nerve provides sensory supply to most of the cheek and emerges from the infraorbital foramen, deep to the orbicularis oculi and levator labii superioris.

The skin in the subunits of the cheek varies in their characteristics. Reconstructive options should take into account adjacent tissue laxity and the likelihood of distorting the surrounding landmarks (eyelids, nose, lips and pinna).

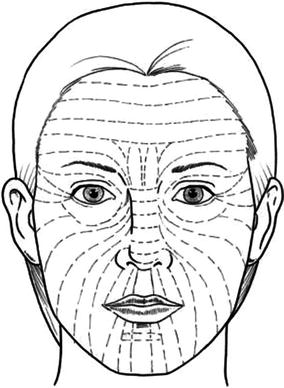

Scars are best placed along the aesthetic borders and consideration should be give to extending the defect, especially in the medial and lateral subunits. When this is inappropriate, scars are best designed to be parallel to the RSTL. The RSTLs in the cheeks are curvilinear or radially fan out from the lateral canthus area (crow’s feet) and offer excellent camouflage for the scars. The skin creases are more prominent in the elderly and can be made more obvious by requesting the patient to smile and shut their eyes tight (Fig. 10.2).

Fig. 10.2

Orientation of RSTL’s

Medial Cheek Defects

Primary Closure

Indications

Small and medium defects

Technique

The defect is modified into an ellipse to lie along the axis of the nasofacial, melolabial and mentolabial folds. The adjacent wound margins are undermined in the subcutaneous plane and closed in layers (Fig. 10.3a–c).

Tips

Asymmetric undermining with greater undermining in the lateral aspect often allows the scars to be placed in the most advantageous position.

Fig. 10.3

Primary closure

Island Advancement Flap

Indications

Small and medium defects adjacent to the alar-facial/nasofacial folds

Technique

The defect is modified to place the medial margins along the alar-facial/nasofacial fold and a parallel lateral margin. Curvilinear incisions are made from the superior and inferior margins of the defect, to delineate a triangular skin island, at least two to three times the length of the defect. The flap is oriented along the melolabial fold. The incision is deepened only through the skin along the entire outline of the flap. The central subcutaneous tissue beneath the flap is preserved to provide the vascularity. The flap subcutaneous tissue closest and furthest from the defect is released incrementally to obtain the necessary mobility. The flap is mobilised into the defect and wound is closed in layers (Fig. 10.4a–c).

Tips

The defect can be enlarged to place the base along the alar-facial and nasofacial folds for best scar camouflage. For larger defects, the curvilinear incision should be made parallel to the cheek RSTLs. The size of the skin pedicle will determine the extent of safe subcutaneous dissection. It is mandatory to retain an adequate subcutaneous island pedicle, the size of which needs to take into account additional tissue release that might be required to obtain the necessary mobility.

Fig. 10.4

Island advancement flap

Buccal Subunit Defects

Primary Closure

Indications

Small and medium defects

Technique

The defect is modified into an ellipse to lie along the axis of the cheek RSTLs (Fig. 10.2). The adjacent wound margins are undermined in the subcutaneous plane and closed in layers.

Tips

Fairly large defects can be closed primarily, especially in the elderly with skin laxity. Care should be taken to avoid damage to the facial nerve.

Rhombic Flap

Indications

Medium-sized defects

Technique

The defect is modified into a rhombus with 60° and 120° internal angles. A rhomboid flap is designed by extending the short diagonal to a distance equal to one of the sides and a further line is drawn from its extremity, parallel to the adjacent side of the defect. The flap is raised in the subcutaneous plane and mobilised into the defect. The wound is closed in layers (Fig. 10.5a–d).

Tips

Given the design of the rhombic flaps, it will not be possible to align all the scars along the RSTL. Four flaps can be designed for any given defect, and the ideal one is chosen based on tissue laxity, best orientation of scars and avoiding distortion of adjacent landmarks.

Fig. 10.5

Rhombic flap

Laterally Based Rotation/Transposition Flap

Indications

Medium/large defects medial, buccal, infraorbital subunits

Technique

The defect is modified into a triangle, with the medial border along the nasofacial/melolabial fold and the base superiorly. A curvilinear incision is made from the base of the defect laterally, along the infraorbital/crow’s feet skin creases, with an “exaggerated” superior extension. The lateral/inferior extension is dictated by the size of the required flap and follows the preauricular skin crease. The flap is raised in the subcutaneous plane and mobilised into the defect. Any dog-ears that develop are corrected along the melolabial fold. The wound is sutured in layers and a drain inserted as required (Fig. 10.6a–d).

Tips

The exaggerated superior extension is necessary to decrease the risk of ectropion. If a large flap is raised, additional “anchoring/suspension” sutures should be placed from the deep surface of the flap to the periosteum overlying the zygoma/zygomatic arch, to prevent flap descent and ectropion. The flap can be extended inferiorly into a neck skin crease (cervico-facial) or even past the clavicle (thoraco-cervico-facial) if required. The cervical extension can be placed behind the lobule of the ear and close to the hairline to camouflage the scars.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree