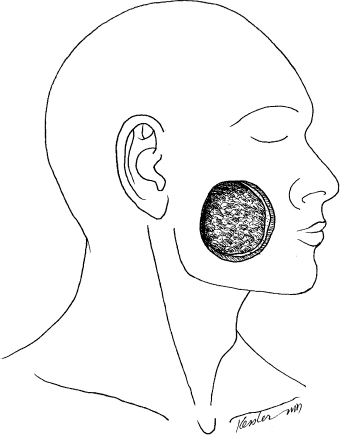

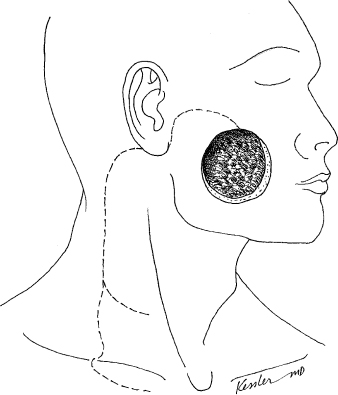

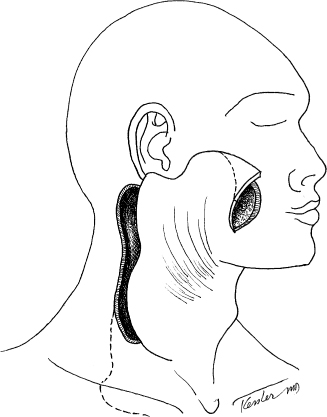

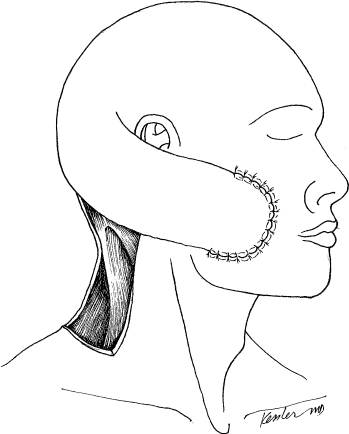

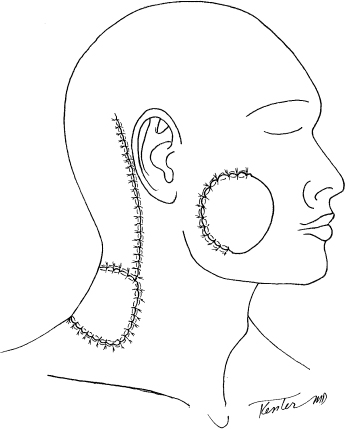

4 Defects of the cheek may range from a superficial cutaneous defect to a through-and-through composite defect. Because of the impact on both aesthetics and function, defects of the cheek represent one of the most challenging areas of reconstruction. The cheek plays an important role both in aesthetics and in the physiology of articulation of speech and swallowing. Defects of this important anatomic area often result in an impairment of these functions. And although the functional component of the cheek is important, the contribution to aesthetics and self-perception cannot be understated. The facial deformity associated with a cheek defect can result in significant social repercussions including selfimposed isolation, depression, and an overall diminished quality of life. For these reasons, reconstruction of the cheek and its related structures requires a thoughtful approach that starts with an appreciation of the anatomy of this region. The cheek extends from the inferior border of the mandible to the inferior orbital rim. Medially, it arises at the lateral aspect of the nasolabial line and extends to the preauricular area. Considered as a distinct anatomic subunit, the cheek is composed of skin, subcutaneous tissue, parotid gland, facial musculature, and a mucosal lining from the inside of the oral cavity. The texture of the skin differs depending on the location. The preauricular skin is pale and thin, whereas the skin over the malar area can be thick and more richly colored. The skin changes with age, generally taking on a thinner epidermis. Immediately deep to the skin of the cheek is the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS). This layer is continuous with the platysma muscle from the neck and extends superficial to the deeper visceral structures of the face. Beneath this layer lies the parotid gland in the preauricular area. The anterior two thirds of the cheek marks the area where the facial nerve branches as they exit the parotid gland along with the superficial layer of facial muscles. The buccal fat pad and inner cheek buccal mucosa lie anterior and deep to the masseter muscle. The anatomic structures involved in the defect will predicate the optimal approach to reconstruction. Sensory supply to the cheek is provided primarily by the second and third divisions of the trigeminal nerve. There is a marked degree of overlap, and should one of these sensory nerves be severed, growth from the adjacent dermatome is common. The superficial facial muscles are supplied by the seventh cranial nerve as it exits the parotid gland. Finally, the arterial supply comes mainly through the external carotid artery via the facial artery. Venous drainage is through the anterior facial vein into the internal jugular venous system. The vascular supply is richly anastomotic with connections from deeper structures and from the contra lateral supply. Ligation of major vessels, such as the facial artery bilaterally, does not have a detrimental effect on healing of this structure as there is also retrograde supply through the angular artery adjacent to the lateral nasal bone. Aesthetically, the facial skin and, in particular, the cheek contribute a great deal to self-perception and the way in which the world perceives us. Because of the cheek’s location on the face, a major defect in this area draws the eye and becomes a center of aesthetic focus. When this defect is coupled with a facial paralysis, the cosmetic impact can be devastating. The most important aesthetic considerations should be the color and texture of the facial skin and preserving facial symmetry. Matching the color and texture of the cheek skin is a rather significant challenge because there are few donor sites that provide a similar match. Commonly, distant donor sites are used for extensive defects; however, this can result in a suboptimal cosmetic result. Although donor sites such as the radial forearm and anterolateral thigh can provide coverage for extensive defects, submental and posterior scalp donor skin may provide a better match. Thoughtful attention to donor-site planning can help in achieving a good result. In addition to the aesthetic implications of a cheek defect, the cheek and its musculature also assist in articulation of speech and the oral phase of swallowing. The muscular tone of the buccinator within the cheek aids in the enunciation of words and oral deglutition. When this dynamic is compromised, oral competency may be hindered, resulting in drooling or food trapping. In contrast, if the buccal region is stiff, trismus may ensue. This too can impact swallowing and speech. The ability to open one’s mouth partially depends on the integrity of the internal lining of the buccal mucosa. We usually attribute trismus to the muscles of mastication. However, patients who undergo a through-and-through cheek resection involving the buccal mucosa require a reconstructive option that does not lead to scar contractures, which can result in trismus. Finally, achieving a cosmetically acceptable, functional, and durable reconstruction requires a careful assessment of the defect, the goals of the reconstruction, and an understanding of the challenges unique to cheek reconstruction. One unique challenge related to cheek reconstruction is the tendency for flaps to pull or drag on the crucial structures such as the lower eyelid or oral commissure. Because of the location of the cheek relative to the eye, mouth, and nose, the weight of a flap or the contractures associated with healing can lead to unintended problems such as lower lid ectropion or oral commissure distortion that can functionally impair a patient. For all the reasons stated, cheek reconstruction is considered a unique challenge to the head and neck surgeon. There is no accepted standard for classifying defects of the cheek, although it is helpful to classify them. Reconstruction of the cheek can be classified in many different ways according to size, location, depth, and the functional deficit. For the purposes of addressing major defects of the cheek, we have organized reconstructive options according to cutaneous defects, defects involving the skin and facial musculature, through-and-through defects, and through-and-through composite defects. Superficial lesions of the cheek may result from malignancy, trauma, or a variety of congenital or acquired deformities. Superficial spreading cutaneous malignancy such as that seen with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) can result in extensive cutaneous defects that leave the underlying facial nerve and mimetic musculature intact. Most tumors of the cheeks are detected in an early stage, and therefore reconstruction can be achieved with primary closure or a variety of rotation advancement flaps (Figs. 4.1, 4.2, and 4.3). Bilobed melolabial and V-Y advancement flaps have been utilized with excellent results. The reconstructive technique of choice is often predicated on the surgeon’s personal experience. As patients age, tissue redundancy increases, making local flaps more available for intermediate-sized defects. As defects become larger, however, the option of local advancement flaps diminishes, and healing by secondary intention, skin grafting, regional flaps, and free tissue transfer become the only options available. In general, healing by secondary intention and split-thickness skin grafts result in contractures and unfavorable scarring that is unpredictable. These techniques should be saved for critically ill patients who could not tolerate a prolonged operative procedure. Although the cervicofacial flap is one of the oldest techniques used for cheek reconstruction, it is also one of the best techniques for the management of superficial cutaneous defects for the cheek. There is no better match for color and texture of the cheek than the skin of the adjacent neck. An understanding of the vascular anatomy of the cervicofacial advancement flap is important when designing and determining the reliability of the flap. ♦ Cervicofacial rotation advancement flaps may be based anteriorly or posteriorly. ♦ The flap can be elevated in the subcutaneous or deep plane, deep to the SMAS and platysma muscle. ♦ Anterior based flaps are most useful for posterior and large anterior defects. The arterial supply is from the facial and submental arteries. ♦ The incision is designed to be placed along the superior boundary of the cheek, down the preauricular crease, and around the earlobe toward the occipital hairline. ♦ If more rotation is necessary, a back-cut can be placed medially in a cervical crease or extending the incision more inferior to the level of the clavicle prior to back-cutting. ♦ For very large defects, the incision may be extended in the subplatysmal plane down to the midchest as a cervicopectoral flap. This will capture additional arterial supply arising from internal mammary perforators. The cervicofacial advancement flap is ideal for a patient with a small to moderate-sized defect that involves the cutaneous tissue. Defects that involve the facial musculature can be managed with a cervicofacial advancement flap; however, the loss of muscle and subcutaneous tissue will result in a hollowing of the cheek. Postoperatively, it should be stressed that the patient should not use tobacco or even be subjected to second-hand smoke, because it may compromise the blood flow to the flap. When a large flap is used, it is important that the wound be well drained so that the suture line is not stressed. In part, this requires that the flap be raised with enough laxity to minimize tension at the distal suture line. Arena1 has been credited with describing the posterior scalping flap as a two-stage technique for managing defects of the cheek and midface. The posterior scalping flap accomplishes many of the objectives of the anterior scalping flap and forehead flap without the disfigurement of a forehead scar. The donor site, in the nape of the neck, is easily camouflaged, particularly in women with long hair. The donor skin derived from the nape of the neck is an excellent color and texture match for the cheek. The shortcoming of this technique is that it is a staged procedure requiring patience and understanding on behalf of the patient and his/her caregivers. The details related to raising the posterior scalping flap can be found elsewhere.1,2 ♦ The patient’s cheek defect is first measured (Fig. 4.11). ♦ The area of non–hair-bearing posterior neck skin that will be transferred to the face is marked. ♦ A vertical midline incision is made from the vertex to the posterior midneck. The length of the incision can be extended in a caudal direction to obtain greater distal flap length. A second, postauricular incision is then made, parallel to the midline incision, along the anterior border of the trapezius muscle. ♦ The two vertical incisions are then connected horizontally at the base of the neck and the flap is elevated, including skin, subcutaneous fat, and the fascia overlying the trapezius and splenius muscles (Fig. 4.12). ♦ Once the posterior scalping flap is raised, if facial reanimation or an intraoral repair is required, this can be performed (Fig. 4.13). ♦ The flap, pedicled superiorly, is then rotated anteriorly, over the ear, and sutured into the recipient site. The vertical midline incision can be extended further superiorly to achieve greater arc of rotation of the flap into the midface. ♦ A split-thickness skin graft is used to resurface the donor site. ♦ Three weeks postoperatively, the pedicle is transected, and that portion of the flap that is not used in the reconstruction is returned to the posterior neck (Fig. 4.14). ♦ The long-term result provides a good color match and functional result (Fig. 4.15). The-donor site skin graft is well hidden (Fig. 4.16). The indications for the approach include medium-sized to large cutaneous defects of the cheek. In select cases of secondary reconstruction, a tissue expander can be used for extensive midfacial defects. This increases the size of the skin available for transfer as well as aids in primary closure of the donor site. Because this flap requires a staged approach with a 3- to 4-week interim period, it is essential that the patient and his/her caregivers are aware of the wound care and patience that are required to endure the perioperative period. The blood supply to the posterior scalping flap is derived from the superficial temporal, supraorbital, and supratrochlear arteries. Therefore, compromise of these vessels is a contraindication to using this technique. Postoperatively, the donor site can be managed with a nonadhesive dressing placed superiorly, whereas the inferior area can be skin grafted. It is essential that the patient not use tobacco because this may compromise blood flow to the distal area of the flap. It is also important that the patient sleep in the decubitus position so as not to place pressure on the vertex of the scalp, which could lead to vascular compromise. After 3 to 4 weeks, the skin flap carrier can be transected and returned to the posterior neck.

Cheek and Neck Reconstruction

♦ RELEVANT ANATOMY

♦ CHEEK RECONSTRUCTION: AESTHETICS AND FUNCTIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

♦ CLASSIFICATION OF CHEEK DEFECTS

♦ THE EXTENSIVE CUTANEOUS DEFECT

Option for Management: Cervicofacial Advancement Flap (Figs. 4.4, 4.5, and 4.6)

Surgical Technique and Considerations (Figs. 4.7 and 4.8)

Patient Selection and Perioperative Management

Option for Management: Posterior Scalping Flap (Figs. 4.9 and 4.10)

Surgical Technique and Considerations

Patient Selection and Perioperative Management

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree