, Paul N. Chugay1 and Melvin A. Shiffman2

(1)

Long Beach, CA, USA

(2)

Tustin, CA, USA

Abstract

The authors focus on the treatment of calf hypoplasia and calf reconstruction post polio or clubfoot deformity. The basic anatomy of the region is described and preoperative marking discussed. The operative procedure is described as well as postoperative care and potential postoperative complications. Observed complications are described with the management of those complications. There is a discussion of compartment syndrome in the lower extremity and its diagnosis and management.

Introduction

Men and women alike wish to have a more muscular and toned physique, and the calf region is not exempt from this. Despite vigorous exercise and body building, some people are unable to attain the definition that they desire in the calf. Many patients who present for consultation want to look good in shorts and skirts but due to a hypoplastic calf say that they are unable to do so. To that end, calf implants of various shapes and sizes have been created to increase volume in the calf. In addition to calf implants, there has been increasing interest in the use of fat to augment the calf in order to avoid foreign body placement [1].

Calf Aesthetics

While the perception of an aesthetic calf may vary from culture to culture and time period to time period, the anatomy is consistent and ultimately gives the basis for calf aesthetics. The shape of the calf is defined primarily by the volume of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. In addition, the crural bones and the subcutaneous fat work in tandem with the muscles to further define the calf. While the bones cannot be altered easily to adjust the aesthetics of the calf, there is liposuction available to treat the subcutaneous fat and implants to address the muscle volume.

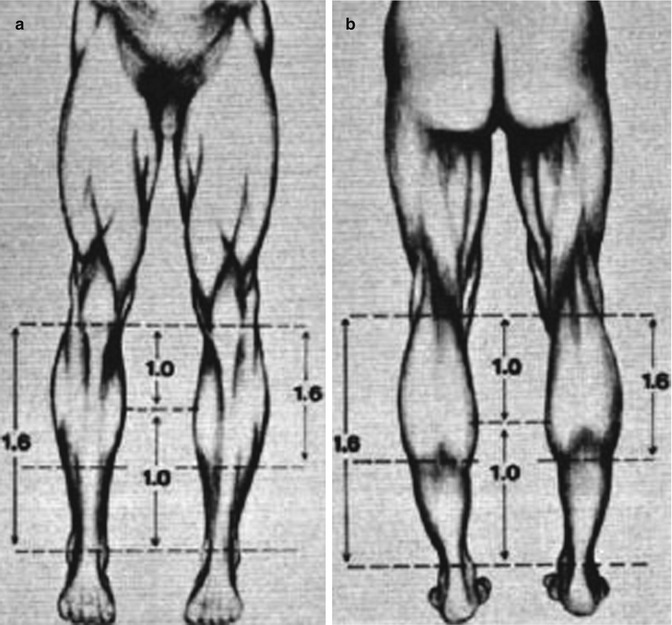

Over the years multiple physicians and mathematicians have tried to define beauty and what constitutes a beautiful human form. It was Howard [2] who first described the ideal length proportions of the calves, basing his paper’s findings on the drawings of Leonardo da Vinci. Howard defined the golden ratio of calf aesthetics to exist when the distance between the ankle and the lower border of the gastrocnemius muscle was equal to the distance between the knee and the most prominent point on the medial curvature of the gastrocnemius muscle; and the entire length of the gastrocnemius should be 1.6 times the former value. This golden ratio correlated to the golden section of 1:1.618 as defined by the Italian mathematician Bonacci or what German astronomer and physicist Johannes Kepler called the “divine proportion” (Fig. 8.1) [3].

History of the Procedure

Over the course of the last 40 years since the introduction of calf augmentation for reconstructive purposes, there have been various surgeons that have proposed novel implant shapes and sizes along with varying locations for the placement of the implants [3–13]. The implant most commonly used today is largely based on the silicone gel implants of Glitzenstein [2]. However, Carlsen [14] was the first to use calf implants back in 1972. His initial implant was made out of Silastic foam. Glitzenstein, in 1979 [2], used calf implants for patients with atrophy of the leg and muscular aplasia. Unlike Carlsen, his implants were designed from silicone gel. In 1984, Szalay [4] introduced torpedo-shaped implants that were placed beneath the fascia. In his technique, however, he did recommend the use of relaxing incisions in the fascia. Aiache in 1991 [13] introduced lenticular-shaped implants. In 2006, Gutstein [9] described a new silicone prosthesis that enhances the curved medial lower leg which he termed a “combined calf-tibial implant.”

The early pioneers of the procedure, Carlsen and Glitzenstein, introduced the implant into a subfascial plane. However, in 2003 Kalixto and Vergara [8] described a calf augmentation with placement of the implant in a submuscular pocket, between the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. The dissection that they proposed was done far away from the union of the gastrocnemius muscles where there were no vessels or nerves that could be damaged. It was noted however that these patients had a more tedious dissection and prolonged recovery than the patients who had undergone subfascial implant placement as described in previous reports. The use of muscle relaxants was paramount in these patients. The rationale for submuscular placement, according to the authors, was that they were able to gain better camouflaging of the implant. In 2004, Nunes described a method for calf augmentation that placed the implant in a supraperiosteal plane associated with fasciotomies. Ultimately, it is at the surgeon’s discretion where to place the implant; however, based on anatomic studies it seems that the subfascial plane is a safe plane that allows for reproducible results with minimal risk of postoperative complications and significantly less pain from the patient’s perspective [12]. It is for this reason that the authors favor a subfascial plane in the medial aspect of the calf.

Indications

Calf augmentation was originally designed to fill defects left following oncologic surgery, after trauma or infection, or due to genetic abnormalities. There are many causes for unilateral or bilateral calf deformities, and they include but are not limited to the following: (1) congenital hypoplasia due to agenesis of a calf muscle or adipose tissue reduction; (2) as a sequelae of clubfoot (talipes equinovarus), cerebral palsy, polio, and spina bifida; (3) due to poliomyelitis or osteomyelitis; and (4) following fractures of the femur and as a result of burn contractures [2, 6, 7, 14]. While calf implants do not improve function of the affected extremity, patients are pleased with the improved aesthetic appearance of the leg after implantation.

Since its initial introduction, calf augmentation surgery has become a widely popular aesthetic procedure to help patients gain more shapely legs. Whether it is a body builder that is looking to “bulk up” the leg despite a vigorous exercise regimen or the average patient who wants a more shapely calf region, there are implants of various shapes and sizes to help add volume to a hypoplastic calf.

Contraindications

Contraindications to the calf augmentation procedure are few. The first is unrealistic expectations on the part of the patient. The patient must be fully aware of the amount of augmentation that can be safely achieved. Patients that desire a more substantial augmentation may be candidates for serial operations but must be prepared for this fact up front. Secondly, patients with severe medical conditions that place the patient in a high ASA classification and at significant surgical risk are not good candidates for elective calf augmentation surgery. The surgeon must always be cognizant of the patient’s circulation to the lower extremity. Compromised circulation in the postoperative period can be disastrous and cause limb loss. A patient who already has preexisting arterial or venous insufficiency may be at an increased risk of limb loss and may be a poor candidate for surgery.

Limitations

Some authors have noted that calf prostheses have the disadvantages of being unable to adequately correct ankle deformities, having a risk of displacement, having a risk of capsular contracture, and potentially having problems with extrusion. While the authors do agree that calf augmentation does not correct ankle deformities, they feel that this can be addressed with judicious fat grafting to the ankle region via small stab incisions at the medial and lateral malleoli.

Relevant Anatomy

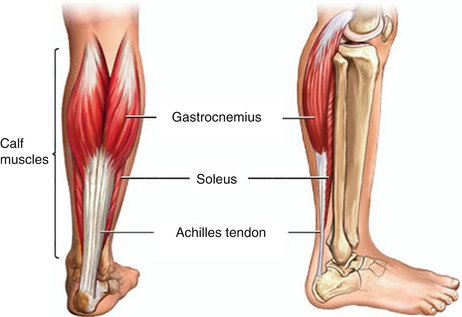

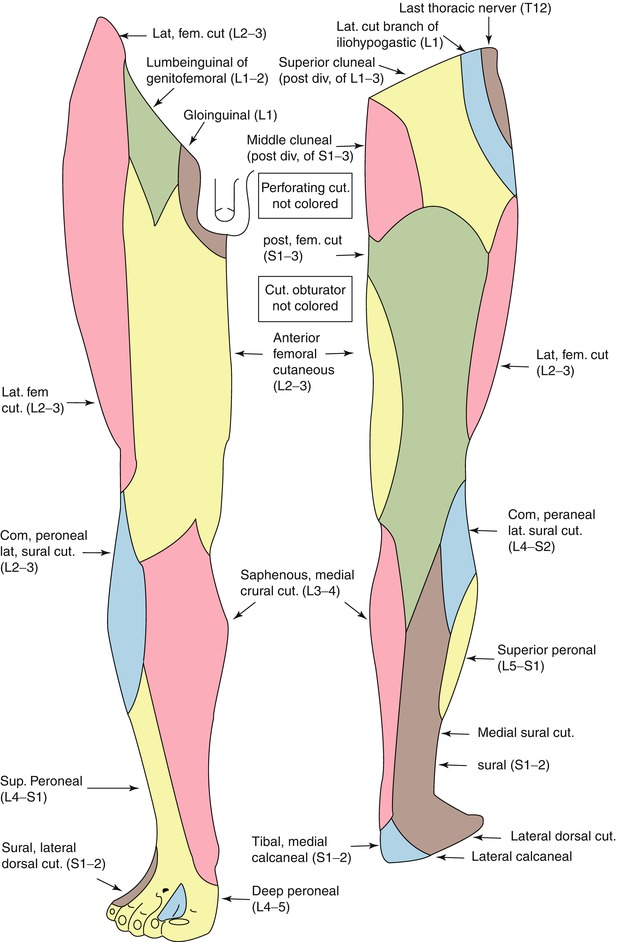

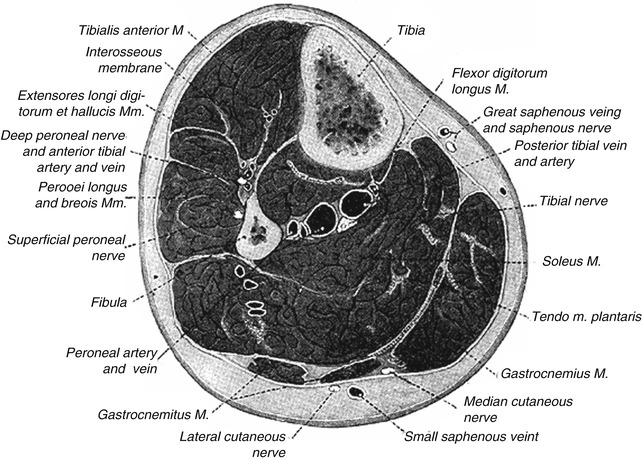

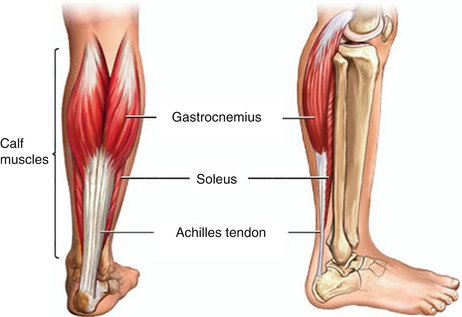

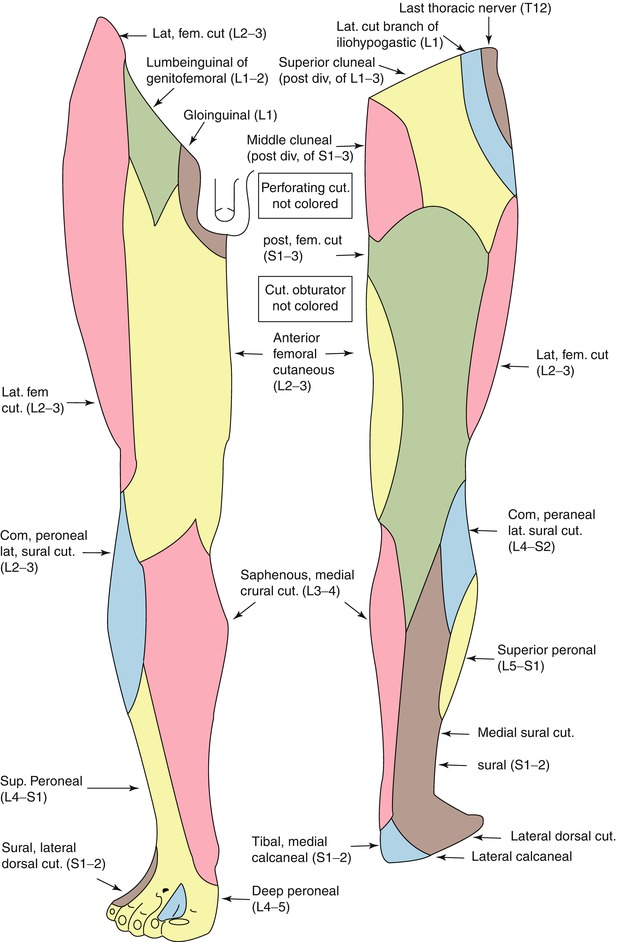

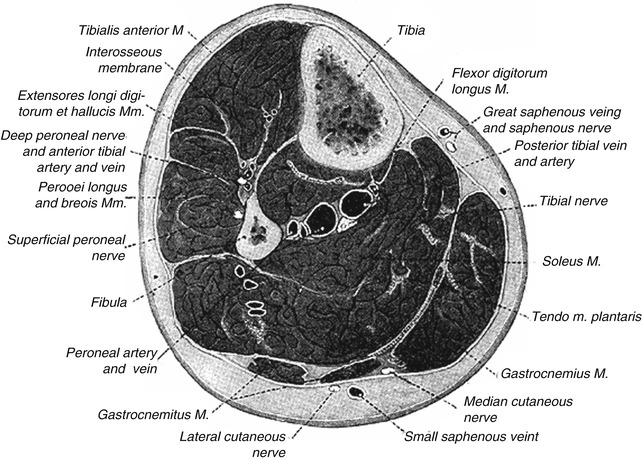

As a result of anatomic studies [12] and operative dissections, the anatomy of the calf region is well understood. The calf is made up of two muscle groups: the gastrocnemius and the soleus (Fig. 8.2). The gastrocnemius has two heads and lies superficial to the deeper soleus muscle. The two heads of the gastrocnemius are connected to the condyles of the femur by strong tendons. The medial and larger head originates from a depression at the upper and back part of the medial condyle and from the adjacent part of the femur. The lateral head arises from an impression on the side of the lateral condyle and from the posterior surface of the femur immediately above the lateral part of the condyle. The fibers of the two heads unite at an angle in the midline of the muscle in a tendinous raphe, which expands into a broad aponeurosis. The aponeurosis, gradually contracting, unites with the tendon of the soleus and forms the calcaneal tendon (Achilles tendon). In performing the dissection to attain a subfascial plane, the lateral and medial cutaneous nerves, branches of the peroneal nerve and tibial nerve, respectively, are potentially encountered. These nerves provide sensory innervation to the skin (Fig. 8.3). The medial sural cutaneous nerve originates from the tibial nerve of the sciatic and descends between the two heads of the gastrocnemius. It can be identified prior to diving between the heads of the gastrocnemius in the upper midline calf region. The lateral sural cutaneous nerve supplies the skin on the posterior and lateral surfaces of the leg and travels in a subcutaneous plane alongside the small (short) saphenous vein, joining with the medial sural cutaneous nerve to form the sural nerve. Major arterial, venous, and nerve structures are deep within the calf and remain undisturbed during a routine calf augmentation procedure (Fig. 8.4). The subfascial plane in the medial calf region is relatively avascular, allowing for creation of a relatively bloodless plane. Care must be taken to avoid injury to the short saphenous vein which lies deep to the investing fascia of the leg and superficial to the gastrocnemius in the midline posteriorly. This vein drains into the popliteal vein in the popliteal fossa.

Fig. 8.2

Major muscles of the calf region: gastrocnemius and soleus

Fig. 8.3

The lateral and medial cutaneous nerve dermatomes are seen here. These are branches of the peroneal nerve and tibial nerve, respectively, and are potentially encountered in dissection for calf augmentation. These nerves provide sensory innervation to the skin in the area

Fig. 8.4

Major neurovascular structures are seen in this cross section of the midportion of the calf. When performing a subfascial augmentation, these structures are relatively safe from injury

Consultation/Implant Selection

The consultation begins with a thorough medical history on the patient. Special attention is taken to ask specifically about trauma to the extremity, history of surgery to the foot or ankle, history of vascular insufficiency which may put blood flow at risk, history of venous insufficiency or leg swelling which may prolong postoperative edema in the lower extremity, and any history of nerve damage or sensory deficits as may be seen in patients with diabetes mellitus. At the time of consultation, the patient is asked what specifically about their calf bothers them. Preoperative goals are assessed at this point. A patient who has unrealistic expectations and is unable to comply with the strict postoperative instructions is deemed a poor candidate for augmentation. Patients who have congenital anomalies, a significant size disparity between the two calves, or bilateral hypoplasia are informed that several surgeries may be required to attain symmetry and achieve the augmentation they desire. In the typical consultation, patients are asked if their deficiency lies primarily in the medial aspect of the calf, the lateral aspect of the calf, or whether they would like a larger calf size overall. The reason for this distinction is to help the surgeon plan the right implant style for surgery.

After completion of the history, the patient’s calves are evaluated. The symmetry of the two sides is assessed and any disparity is brought to the attention of the patient. Although the majority of patients present with a preexisting asymmetry of the calves, not many patients note the difference and this can be a source of medicolegal matters in the future. If the patient suffers from clubfoot deformity or a previous bout of polio, leg asymmetry is noted. The physician then evaluates the quality of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle. A person who has very thin tissues or significant hypoplasia of the calf may not be able to adequately accommodate a large implant. The patient’s calves are measured in circumference at the midportion of the calf. A second measurement, from the popliteal fossa (proposed incision line) to the insertion of the Achilles tendon, is also taken. Having this second measurement allows one to assess the maximum length of implant that can be accommodated in the calf.

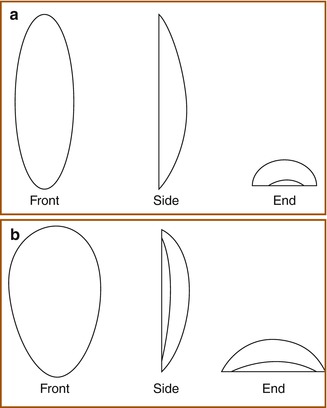

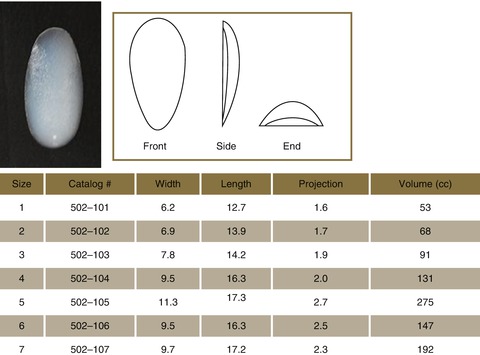

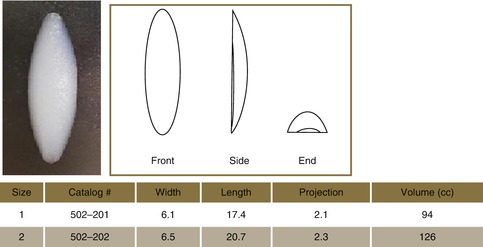

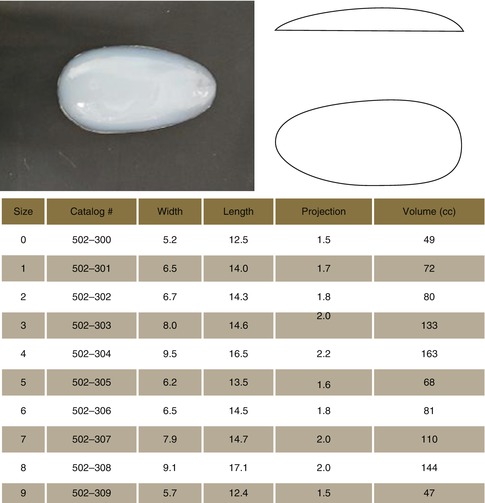

When determining the type of implant to use, the determination is based on the desires of the patient. However, the authors also take into account the length from the popliteal fossa to the insertion of the Achilles tendon to better define the length that will be accommodated. If the patient merely wishes to have more definition in the calf, then the style 2 implants will be used in most cases. With the style 2 calf implant, there is a greater enhancement of the medial calf muscle (Fig. 8.5). If, however, the patient wishes to have more overall volume to the calf region and is looking for more of a blocklike appearance to the calf, then the style 1 implant is favored (Fig. 8.5). With the style 1 implant, there is a greater enhancement of the entire calf region, which in our practice is best suited for patients who already have a great deal of muscle volume (e.g., body builders) and just want an overall increase in volume. Style 3 is used for lateral head augmentation and is rarely used. Each of the different style implants has a range of sizes to fit each patient need. Regardless of the implant chosen, the position of the implant is still in the subfascial plane and minimizes dissection around key neurovascular structures. With experience, the surgeon will be better able to determine the best implant for each patient.

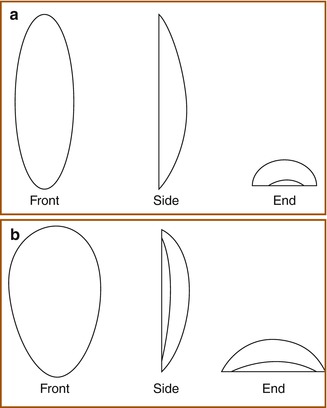

Fig. 8.5

(a) Calf implant style 2 (Courtesy of AART (Aesthetic and Reconstructive Technologies, Inc., Reno, NV)). (b) Calf implant style 1 (Courtesy of AART (Aesthetic and Reconstructive Technologies, Inc., Reno, NV))

Available Implants

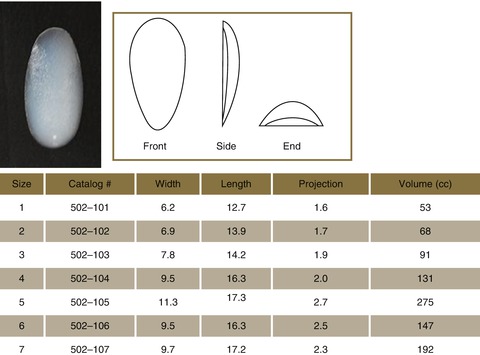

Style 1 is the authors’ preference for bulky calf augmentation (Table 8.1). Style 2 is the authors’ preference for medial calf augmentation (Table 8.2). Style 3 is the authors’ preference for lateral calf augmentation (Table 8.3).

Table 8.1

Style 1 (Aesthetic and Reconstructive Technologies, Inc., Reno, NV)

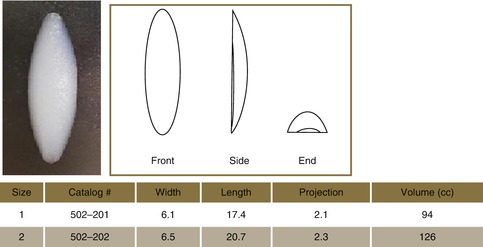

Table 8.2

Style 2 (Aesthetic and Reconstructive Technologies, Inc., Reno, NV)

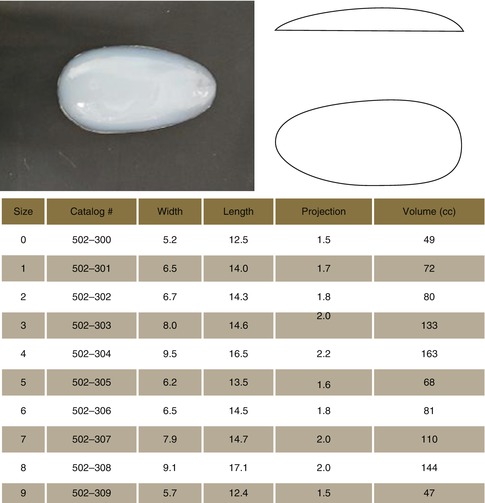

Table 8.3

Style 3 (Aesthetic and Reconstructive Technologies, Inc., Reno, NV)

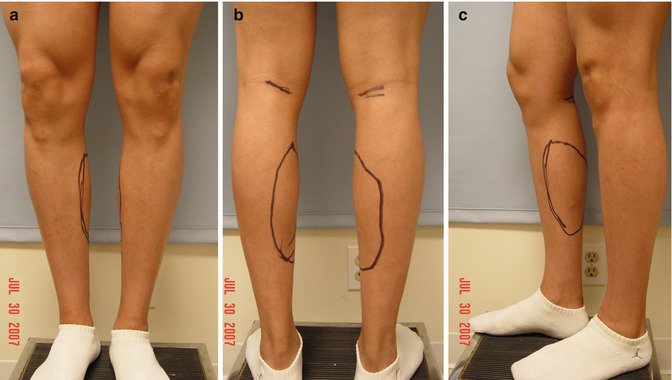

Preoperative Planning and Marking

On the day of the surgery, the patient is met in the preoperative holding area. It is here that the patient’s consent is verified and again risks, benefits, and alternatives are reviewed with the patient. With the patient in the erect position, the proposed site of incision is marked, measuring approximately 5 cm. The site of incision should be in line with the patient’s natural crease in the popliteal fossa. To help accentuate this crease and make marking easier, the patient may be asked to hold on to a stationary object and flex at the knee. Once the site of the incision is marked, the site of the proposed implant is marked taking into account the patient’s anatomy and existing deficit along with the desires of the patient (Fig. 8.6).

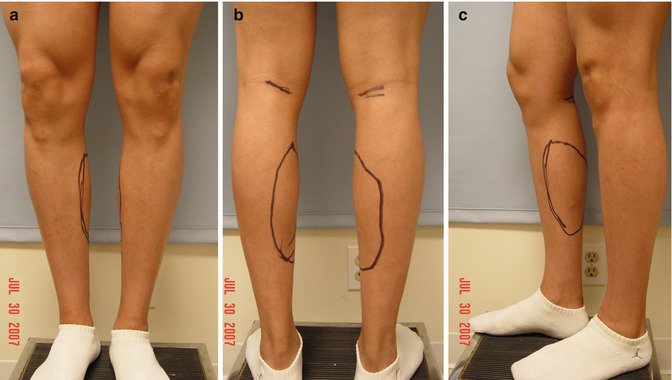

Fig. 8.6

(a–c) Preoperative markings for calf augmentation surgery. Note the site of the incision in the popliteal fossa and the outline of the site for calf augmentation. The markings for implant position are done in concert with the patient to maximize patient satisfaction postoperatively

Operative Technique

Medial Calf Augmentation

The surgery can be performed under general anesthesia or under simple local anesthesia; however, our preference is to use monitored anesthesia care with propofol and ketamine. Two grams of Ancef are administered prior to the incision for prophylaxis (if allergic to penicillin or cephalosporin, then intravenous (IV) clindamycin 300 mg is administered). The patient is repositioned in the prone position after administration of anesthesia. The calves are then prepped with Betadine, and each calf is injected with a total of 50 mL of 1 % lidocaine with epinephrine in the area of proposed implant placement. The patient is then reprepped and draped in sterile fashion. A 5 cm incision is made in the popliteal fossa in line with preoperative markings (Fig. 8.7). Dissection is performed through the subcutaneous tissues using a combination of blunt dissection with gauze and a hemostat. Further dissection and hemostasis can be achieved with electrocautery (Fig. 8.8). Dissection is carried to the level of the popliteal fascia (Fig. 8.9). On reaching the fascia, a #15 blade scalpel is used to make a transverse incision. This is extended with Metzenbaum scissors medially and laterally. At this point 2-0 Vicryl stay sutures are placed in each section of the fascia (Fig. 8.9). A subfascial plane, beginning beneath the popliteal fascia and extending into the deep investing fascia of the leg, is then dissected using blunt finger dissection and a spatula dissector, ensuring an adequate plane for the implant in the medial aspect of the calf (in line with preoperative markings/patient wishes) (Fig. 8.10). While performing this dissection, care is taken to avoid injury to the short saphenous vein which runs in the midline posteriorly and lies deep to the investing fascia of the leg along the surface of the gastrocnemius. Once a sufficient pocket is dissected, the pocket is irrigated with a solution containing normal saline, Betadine, Ancef, and gentamicin. Fifteen milliliters of 0.5 % Marcaine is injected into the pocket for postoperative analgesia. A lozenge-shaped implant is then placed into the pocket, making sure to attain symmetry (Fig. 8.11). Once the implant has been placed, symmetry is assessed. At this point closure is begun. The fascia is re-approximated with 2-0 Monocryl suture in interrupted fashion (Fig. 8.12). The deep dermis is re-approximated with 3-0 Monocryl suture in buried fashion. The skin is closed in subcuticular fashion with 4-0 Vicryl suture or with interrupted 4-0 silk sutures (based on surgeon preference). The same procedure is mirrored on the contralateral side. The legs are wrapped with Coban and the patient is then taken to the postanesthesia care unit (PACU).

Fig. 8.7

Incision at the popliteal fossa

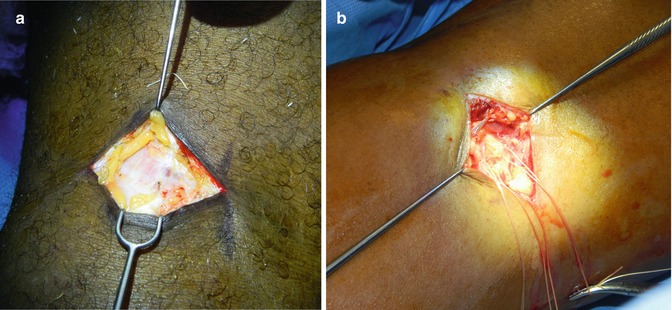

Fig. 8.8

Dissection through the subcutaneous tissues using electrocautery. Single-tooth hooks are used for retraction of the skin

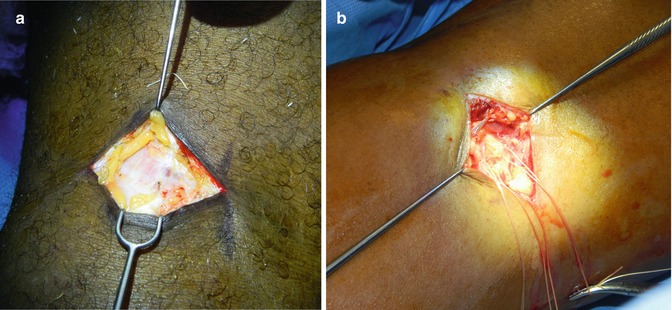

Fig. 8.9

(a) Deep investing fascia of the leg (glistening). (b) Incision has been made through the investing fascia with stay sutures being placed in the superior and inferior aspect of the cut fascia. The authors’ standard is to put one up and two down as the inferior portion of the fascia tends to retract, and secure fascial sutures are key to helping re-approximation at the end of the case

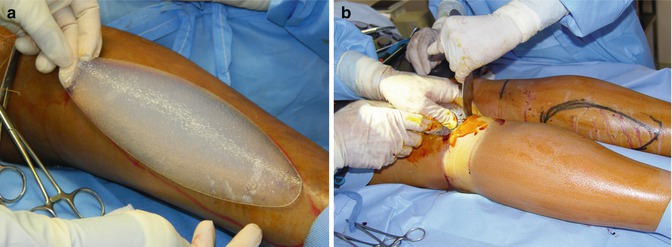

Fig. 8.10

Dissection of the subfascial pocket. (a) After initial dissection of the pocket using blunt finger dissection, a spatula dissector is used to further dissect the pocket. (b) The dissector tip is noted in the midportion of the calf tenting up the skin overlying the subfascial pocket. (c) At completion of dissection, there is an ample pocket that has been created with the gastrocnemius muscle seen below

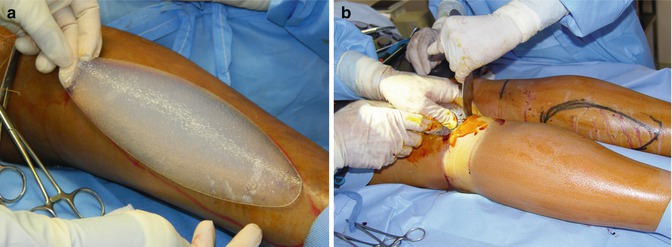

Fig. 8.11

(a) The implant (style 2, size 2) being demonstrated in its position in the right medial calf. (b) Insertion of the prosthesis into the subfascial pocket taking care to fold the implant along its long axis to facilitate positioning

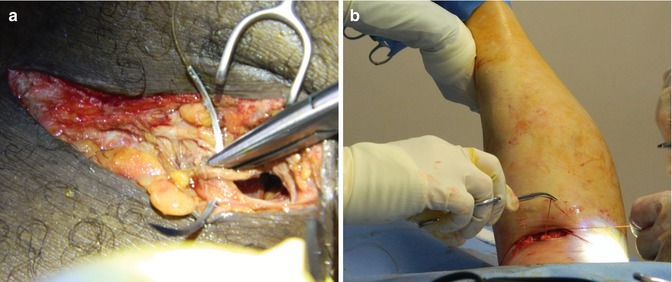

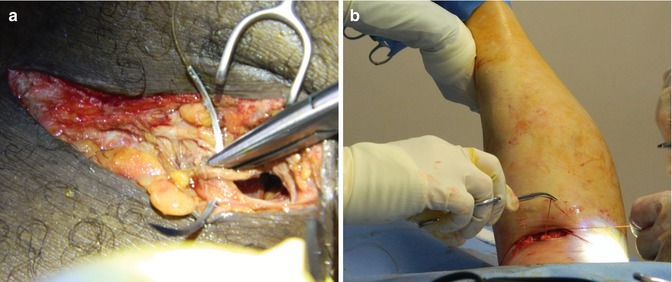

Fig. 8.12

(a) Closure of the deep investing fascia of the leg using 2-0 Vicryl suture. (b) To facilitate closure and take tension off of the ends of the fascia, the knee is flexed by the assistant

Lateral Calf Augmentation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree