, Paul N. Chugay1 and Melvin A. Shiffman2

(1)

Long Beach, CA, USA

(2)

Tustin, CA, USA

Abstract

The authors focus on the treatment of buttock hypoplasia and discuss the basic anatomy of the region. Preoperative markings are described as well as the operative procedure. Postoperative care and potential postoperative complications are discussed as well as observed complications and the management of those complications. Special attention is paid to the postoperative care of sciatic pain that may be associated with the procedure. There is a comparison of buttock augmentation with implants to fat with specific reference to published data to that effect.

Introduction

The popular media has put a premium on particular physical attributes that are attractive, and none of these have been more prominent in the last two decades than the buttocks. Stars such as Shakira, Jennifer Lopez, and Kim Kardashian have been revered for their round, plump bottoms (Figs. 6.1 and 6.2). Cultures such as those in South America, which openly display the human form, have increasingly sought ways to contour the gluteal region as it is considered a very important secondary sexual characteristic. To that end, many patients present to aesthetic practices for augmentation of the buttocks, in the hope of making them look shapelier. In 2006, according to the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, 2,556 gluteal augmentations were performed in the United States [1]. When considering the patients that are undergoing buttock augmentations, the vast majority of patients are in the 20–39-year age group [2, 3]. Whether fat grafting to the buttocks or implant placement is the right choice for the patient is at the discretion of the surgeon based on physical findings at the time of consultation. Herein, we will discuss the evaluation of the gluteal region, discuss the gluteal augmentation procedure, and recommend the patients that are best suited for implant surgery versus other options.

Fig. 6.1

Jennifer Lopez

Fig. 6.2

Kim Kardashian

Gluteal Aesthetics and Classification Systems

Although the standards to define a beautiful buttock region may vary slightly from culture to culture, there is little debate about the allure of the hourglass female figure. Singh [4] proposed that there is one female body shape (full buttocks and a narrow waist) that men universally find attractive; and this is defined by an ideal female waist to hip ratio (WHR) of 0.7. The waist to hip ratio is defined as the ratio of the circumference of the waist at its narrowest point to the circumference of the thighs at the level of maximal lateral projection (level of the trochanteric depression). (See Chap. 7 for more details.) A successful gluteal augmentation procedure is therefore defined as one in which the surgeon successfully brings the woman as close to the ideal WHR of 0.7 as possible [5].

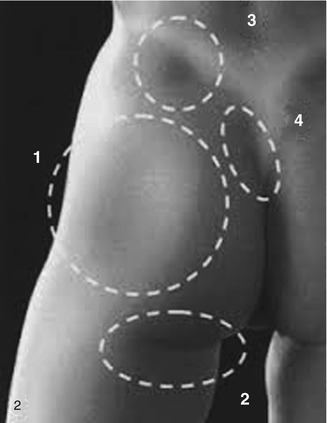

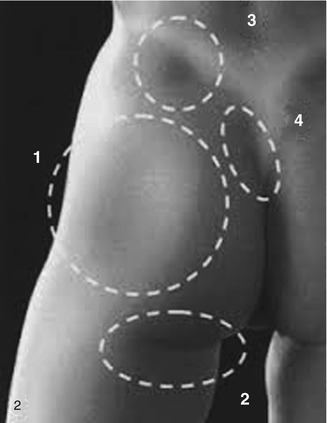

Since the advent of body contouring surgery, many different ways of evaluating the gluteal region have been proposed to help surgeons achieved optimal results in contouring of and around the buttocks. In 2004, Cuenca-Guerra et al. [6] first reported their analysis of more than 24,000 images of the gluteal area taken from various media sources. He defined four recognizable characteristics of an aesthetically pleasing gluteal region (Fig. 6.3):

Fig. 6.3

Cuenca-Guerra Buttock Landmarks. Take note of the following: 1 A mild lateral depression that corresponds to the greater trochanter of the femur. 2 Short infragluteal folds that do not extend beyond the medial two-thirds of the posterior thigh. 3 A well-defined dimple on each side of the medial sacral crest that correspond to the posterior-superior iliac spines (PSIS). 4 A V-shaped crease (or sacral triangle) that arises from the proximal end of the gluteal crease

1.

Two well-defined dimples on each side of the medial sacral crest that correspond to the posterior-superior iliac spines (PSIS)

2.

A V-shaped crease (or sacral triangle) that arises from the proximal end of the gluteal crease

3.

Short infragluteal folds that do not extend beyond the medial two-thirds of the posterior thigh

4.

Two mild lateral depressions that correspond to the greater trochanter of the femur

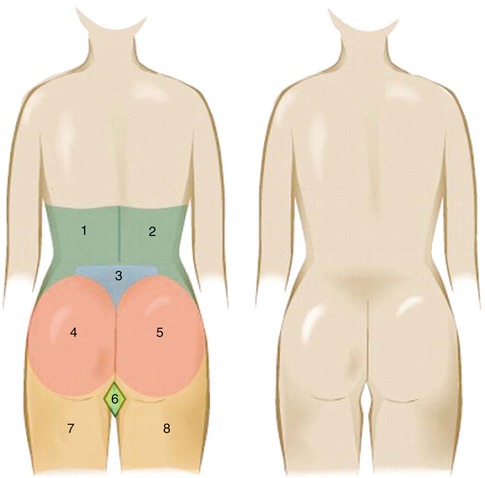

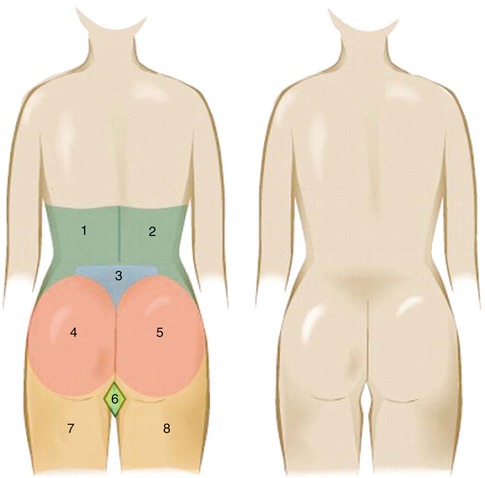

Centeno in 2006 [7] described one of the other primary methods for evaluation of the buttocks to help plan body contouring procedures. From the posterior-anterior view of the patient, he defined eight gluteal aesthetic units that help form an aesthetic bottom. By his estimation, the gluteal region consists of two symmetrical “flank” units, a “sacral triangle” unit, two symmetrical gluteal units, two symmetrical thigh units, and one “infragluteal diamond” unit (Fig. 6.4). Accentuation of these units with liposculpture, buttock implants, or hip implants would aid in producing a more aesthetically pleasing contour to the buttock region. When considering procedures that involve incisions, Centeno recommended careful incision placement to respect the junctions of these aesthetic units.

Fig. 6.4

The 8 gluteal aesthetic units of Centeno include 1, 2 two symmetrical flank units, 3 one sacral triangle unit, 4, 5 two symmetrical gluteal units, 7, 8 two symmetrical thigh units, and 6 one “infragluteal diamond” unit

Mendietta in 2006 [8] described a gluteal evaluation system where he analyzed the underlying bony framework of the buttocks, the skin, and the subcutaneous fat distribution, in addition to the musculature of the region. First, he recommended an evaluation of the pelvic frame. Next, the gluteus muscle is evaluated in its height and width. He divided the buttock into four quadrants: upper inner, lower inner, upper outer, and lower outer. Determination of volume addition should be based on analysis of these four quadrants of the buttock. Any additional procedures that need to be performed (e.g., buttock lift or liposculpture) can then be determined by the analysis of these defined criteria.

History of the Procedure

Many surgeons on many continents have added to the knowledge base and growing amount of literature on gluteal augmentation procedures. Gluteal augmentation surgery began in 1965 when Bartels first used a mammary prosthesis (Cronin prosthesis) in the gluteal region to produce a more round and supple bottom side [9]. Subsequently, Cocke in 1973 [10], Douglas in 1975 [11], and Buchuk in 1980 [12] described their early experiences with aesthetic gluteal augmentation. Robles in 1984 [13] reported on his placement of a submuscular gluteal implant with an incision in the medial sacral line. In 1991, Gonzalez Ulloa [14] described his 10-year experience with buttock augmentation. Recently, Vergara [15] presented his 15-year experience with the procedure.

Over the past three decades of advancements in gluteal augmentation, surgeons have proposed various methods of performing the augmentation to achieve the most aesthetic result with minimal complications. Gonzalez Ulloa [16] is regarded by most as one of the great pioneers and grandfathers of buttock augmentation, having begun his work late in the 1970s and presenting his work in Mexico City in 1977. A large portion of his early procedures were performed on patients who had suffered severe damage and/or deformation of the gluteal region due to silicone, collagen, or guaiacol injections. In his early reports of the procedure, he recommended placement of the implant above the gluteus maximus muscle with an incision in the subgluteal sulcus. This subcutaneous plane has largely been abandoned by many surgeons as it can produce an unnatural look and has a large risk of implant migration. Robles in 1984 [13] reported on placement of implants in the submuscular plane with an incision along the medial sacral line. In 1995, the primary author evaluated Robles’ work and felt that the potential for injury to the sciatic nerve was too great and began working to place gluteal implants in a more superficial submuscular space, which would later be termed the “intermuscular” space. His initial work on 22 gluteal augmentations performed in the intermuscular space was published in early 1997 as a “modification of buttock augmentation” [17]. The intermuscular space was defined as the potential space that was visualized between the gluteus maximus above and the medius and minimus below during surgical dissection. An implant could easily be placed into this position, thereby minimizing trauma to the gluteus maximus muscle and avoiding injury to deeper muscles and neurovascular structures. Vergara and Marcos [15] later described their use of the “intramuscular” plane for gluteal implant placement based on cadaver dissections which showed an intramuscular anatomic space available for augmentation, larger in size than the submuscular space previously noted by Robles [13]. This paper validated the placement of a silicone prosthesis between the fasciculi of the gluteus maximus muscle and avoided the deeper plane which would put the patient at greater risk of sciatic nerve injury. However, this description differed from that of the primary author in that Vergara attempted placement of the implant within the gluteus maximus muscle rather than placing the implant fully under the maximus muscle. Vergara, along with other authors that use the intramuscular plane, emphasizes the need for maintaining a superior muscle flap covering the implant that is at least 3 cm thick [17–19]. Later in 1997 Peren et al. [20] described their work with augmentations done in the subfascial plane. This was then revisited in 2004 by de la Pena [21]. The limitation of the subfascial plane is that large volume implants with significant projection increase cannot be used due to the tightness of the pocket. Additionally, because of its more superficial position, there is a greater chance of implant palpability. Most recently, Gonzalez [22] introduced the XYZ method for gluteal augmentation. Gonzalez uses the same intramuscular plane as described by Vergara but introduces a means of orienting the gluteal implants to maximize symmetry and aesthetic results. He defines a point X as representing the center of the gluteus maximus muscular mass at the site of access to the submuscular plane. He performs dissection cephalically up to a point Y which is just past the lower iliac spine. Then along a vector named line G, he dissects caudally down to a point Z which is at the level of the trochanter and still beneath the gluteus muscle. Gonzalez asserts that his technique is important in gluteal augmentation as natural and reliable pelvic landmarks are used for dissection as preoperative cutaneous markings often provided a distorted view of the anatomy when the patient is in the prone position for surgery, helping to produce more reliably aesthetic outcomes [22].

In considering incision placement for the procedure, early surgeons worked through bilateral infragluteal sulcus incisions [9–12, 14]. This was then followed by bilateral coccygeal incisions as used by Gonzalez Ulloa [9]. Later surgeons felt that less incisions could lead to less postoperative morbidity. For this reason, incision placement turned to use of a single 5–7 cm incision hidden in the intergluteal cleft [13–15, 17, 18]. Mendietta in 2005 [23] presented his approach to gluteal augmentation, suggesting two paramedian incisions in order to decrease the risk of wound dehiscence. By placing two incisions, there was less trauma to the incision and tension was minimized. Most recently, in 2007, Badin and Vieira [24] discussed their experience with a small intergluteal crease incision with pocket dissection using endoscopic technology aimed at minimizing the risks of sciatic nerve injury and maximizing aesthetic gain.

Implants Used (Table 6.1)

Table 6.1

Types of buttock implants used

|

Implant type

|

Advantages

|

Disadvantages

|

|---|---|---|

|

Semisolid elastomer

|

Does not rupture

|

Firmer buttocks

|

|

Cohesive gel

|

Soft and natural feel

|

Possibility of rupture

|

|

Less palpable

|

Not available in the United States

|

In 2006, De la Pena [25] described the history of gluteal augmentation and briefly discusses the differences in implants used for buttock augmentation between the United States and countries outside it. He notes that there are two primary types of buttock implants available commercially: semisolid elastomer implants and cohesive gel implants. In 2012, Bortoluzzi Daniel [19] sought to evaluate the durability of gluteal prostheses and noted that cohesive gel implants, as used in his native Brazil, had a high failure rate and risk of rupture when compared to the semisolid elastomer-type implants used by surgeons in the United States. Cohesive gel implants have a shortened useful lifespan due to the fact that creases can sometimes fold in the implant itself combined with the significant force of compression produced by sitting on the implants. Studies performed on breast augmentation patients suggest that cohesive gel implants may need replacement in 20–40 % of patients at 8–10 years. Based on the research of Bortoluzzi Daniel, this half lift is considerably shorter for gluteal implants because of the constant tension that they are subjected to. Although the search for the ideal implant continues, the semisolid elastomer implant and cohesive gel implant have underscored the major developments in buttock augmentation surgery.

The large majority of the US companies are making implants that are semisolid and rigid. Implantation of these types of implants does have the advantage of not rupturing; however, it can lead to a more firm buttock region. This is in contrast to the implants frequently used in Latin American countries that are often made of a cohesive gel within a thick and resilient silicone shell (Fig. 6.5). These implants are softer and have a more natural feel according to physicians that use them. The major downside of these implants, however, is the risk of rupture. In our own practice, it is our feeling that implants made by AART (Aesthetic and Reconstructive Technologies, Inc., Reno, NV) not only provide rigidity needed to provide a solid augmentation but are pliable enough to make them natural in their look and feel when implanted.

Fig. 6.5

Cohesive gel implants used for gluteal augmentation

Relevant Anatomy

In Centeno’s [7] work, there are four superficial landmarks that should be identified and potentially accentuated in buttock augmentation/contouring. These four areas are the sacral dimples (overlying the PSIS), the sacral triangle (formed by the two PSIS and the coccyx inferiorly), the lateral depression correlating to the greater trochanters of the femur, and the short infragluteal fold. When performing buttock augmentation, one should be careful not to obliterate these landmarks and may even consider the adjunctive use of liposculpture to further enhance these landmarks in addition to performing the buttock augmentation.

The buttock region has investing fascia that helps prevent gluteal ptosis and provide structural support to the gluteal area. The superficial fascia as described by Lockwood [6] fuses with the deep gluteal fascia at the level of the infragluteal fold to create a tight adherence which needs to be respected in augmentation and liposculpture procedures [26]. A violation of this tight adherence can lead to significant gluteal ptosis which is difficult to reconstruct if lost. In addition to helping to create the infragluteal fold, the superficial fascial system along with the deep investing fascia of the gluteus muscle is key to providing a sound closure at the end of the procedure and should be employed in a layered closure of the midline buttock incision.

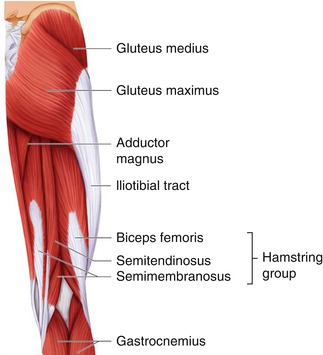

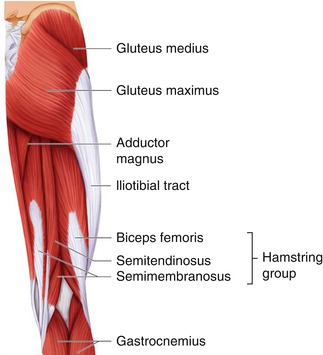

The muscles that comprise the buttock region are several, but the primary volume is formed by the three gluteus muscles (Fig. 6.6). The gluteus maximus muscle originates on the fascia of the gluteus medius muscle, the external ilium, the fascia of the erector spinae, the dorsum of the lower sacrum, the lateral coccyx, and the sacrotuberous ligament [27]. It inserts on the iliotibial tract and proximal femur. The muscle is a powerful extensor of the flexed femur and provides lateral stabilization of the hip. The gluteus medius originates on the external ilium and inserts on the lateral greater trochanters. It acts to abduct the hip and thigh and helps to stabilize the pelvis during standing and walking. During dissection, it can be differentiated from the gluteus maximus because of its vertically oriented fibers. The gluteus minimus originates on the external surface of the ilium and inserts on the anterior-lateral greater trochanter. This muscle abducts the femur and also serves as a pelvic stabilizer.

Fig. 6.6

Gluteal muscles (maximus, medius) depicted and their relationship to key muscular structures in the lateral hip/thigh and lower extremity. Gluteus minimus is not depicted

Blood supply in the gluteal region is rich and reliable. The musculocutaneous structures in the gluteal region are largely supplied by the perforating branches of the superior and inferior gluteal arteries, which are terminal branches of the internal iliac artery [28]. Accessory blood supply comes from the deep circumflex iliac, lumbar, lateral sacral, obturator, and internal pudendal arteries. The superior and inferior gluteal veins provide venous drainage of the region. When considering dissection of the gluteus muscle, one must be careful to avoid sharp dissection very close to the sacrum and sacrotuberous ligament as injury to the gluteal arteries can occur [22].

There is a rich complex of nerves that innervate the muscles of the buttock region and provide sensation to the overlying skin. They largely originate from the lumbosacral plexus. The gluteus maximus is innervated by the inferior gluteal nerve. This nerve comes from the pelvis to the gluteal area, crossing the great sciatic foramen posteriorly and in a way medial to the sciatic nerve. It divides into three collateral branches: the gluteus (motor nerve of the gluteus maximus), the perineal, and the femoral (sensory nerve). The branches of the inferior gluteal nerve are like a crow’s foot when dividing into its branches. These branches then course between the gluteus muscle and its anterior fascia, with the largest segments (fillets) of this nerve being close to the sacrum and sacrotuberous ligament. It is for this reason that undermining inside the gluteus muscle must never be performed to close to the sacrum, the sacrotuberous ligament, or the sciatic tuberosity [22].

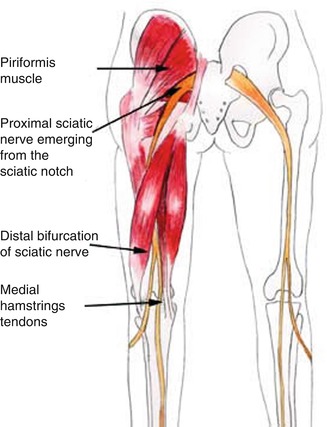

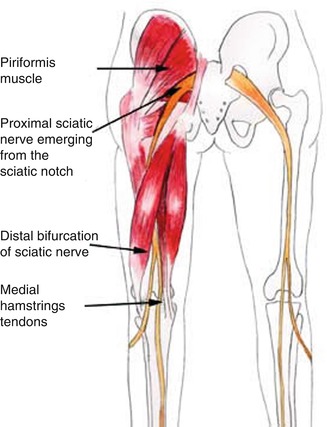

The gluteus medius and minimus are innervated by the superior gluteal nerve. Sensation to the gluteal region and lateral trunk comes from several sources: the dorsal rami of the sacral nerve roots 3 and 4, the cutaneous branches of the iliohypogastric nerve, and the superior cluneal nerves that originate from the L1, L2, and L3 roots. The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves, branches of the L1 nerve root, supply the skin overlying the lateral gluteal region and can be injured with aggressive lipocontouring of the lateral buttock region. Lastly, the sciatic nerve is the largest nerve of the body and originates from the nerve roots of L4 through S3 (Fig. 6.7). It exits the gluteal region through the greater sciatic foramen below the piriformis muscle and above the superior gemellus muscle to enter the posterior compartment of the thigh. Compression or injury of the sciatic nerve may cause loss of function of the posterior thigh compartment muscles and all muscles of the leg and foot and loss of sensation in the lateral leg and foot as well as the sole and dorsum of the foot [29].

Fig. 6.7

Course of the sciatic nerve with its exit at the inferior pole of the gluteus muscle. Because of its course, this nerve is at risk for injury during submuscular placement of a gluteal prosthesis either by traction injury or by direct compression by the implant

Indications

Gluteal augmentation with implants is indicated in patients who suffer from insufficiency of the gluteal region. These patients are typically young and have good muscle and skin tone but lack volume or definition to the gluteal region. Gluteal implants are also indicated in patients who suffer from ptosis of the gluteal region and wish to have a perkier appearance to the buttocks. Another set of patients that benefit from gluteal augmentation with implants are those who have a congenital gluteal deformity or acquired asymmetry (due to trauma, postoperatively, or post-oncologic resection).

Contraindications/Limitations

Relative contraindications to the procedure are few and typically deal with tissue irregularities in the area to be augmented. One such limitation is a depressed scar in the buttock area which may require adjunctive procedures to cause a release of the scar. Patients who have suffered from radiation to the area have a relative contraindication to surgery as their tissues may be indurated and healing may not be optimal postoperatively. Another patient who may have a relative or absolute contraindication to implant surgery is the patient who presents with deficiency of the lateral and inferior portions of the buttocks. When performing buttock augmentation with implants, the inferior pole remains largely unchanged as too caudal a dissection can put the sciatic nerve at risk of injury. For that reason patients who have a significant deficiency at the lower pole should be counseled to consider fat grafting and implant augmentation. Similarly, deficits in the lateral aspect of the butt are largely unchanged with implant augmentation. Although there will be a slight improvement in the lateral curvature of the buttocks, significant deficits may best be treated with fat grafting or possibly a hip implant. Patients who suffer from autoimmune diseases may be at increased risk postoperatively and should be counseled appropriately prior to pursuing any implant surgery. A patient who presents with unrealistic expectations or suffers from major psychological illness is not an appropriate candidate for buttock augmentation surgery.

Consultation/Implant Selection

A thorough history and physical are paramount to preventing complications at the time of buttock augmentation. Questions are posed regarding the patient’s reasonable attempts to build the muscle with conventional means. During the consultation, patient’s expectations are managed and assessment of the patient’s mental state is undertaken. It is made clear to the patient the expected augmentation that can be achieved, and limitations of the procedure are also explained.

After completion of the history portion of the consultation, an evaluation of the patient’s buttocks is made. Any asymmetries or defects are pointed out to the patient. The patient’s muscles are then evaluated. The skin and fat content are similarly assessed at this time as a patient with minimal adipose and thin skin is more at risk for implant palpability. Measurements of the patient’s buttocks in the transverse axis are then taken in the midportion of the gluteal region beginning 1 cm lateral to the intergluteal crease and ending at the lateral palpable edge of the buttock muscle. This measurement allows the physician to choose an implant that will adequately fill out the gluteal region and is analogous to determining the base width in breast augmentation. Measurement of the vertical height of the buttock is taken from its most cranial portion to its most caudal portion 2 cm short of the infragluteal crease.

Available Implants (Tables 6.1, 6.2, 6.3, and 6.4)

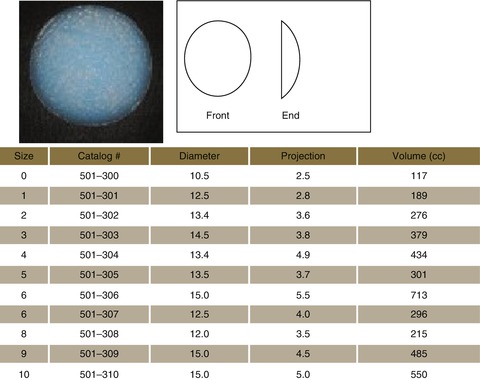

The authors’ preference is the style 3, round implant.

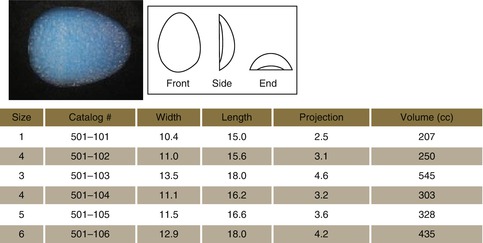

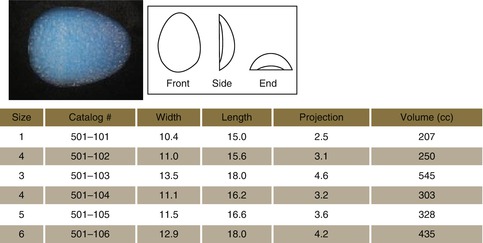

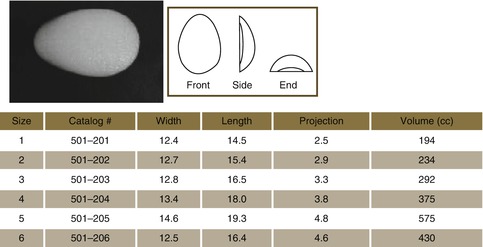

Table 6.2

Style 1 buttock implants (Aesthetic and Reconstructive Technologies, Inc., Reno, NV)

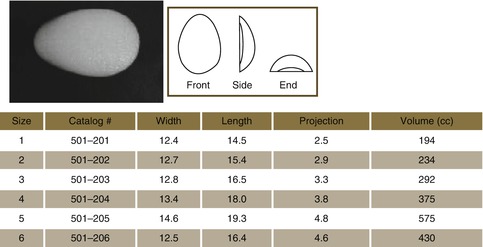

Table 6.3

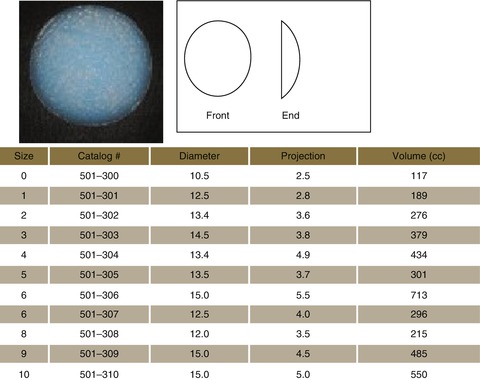

Style 2 buttock implants (Aesthetic and Reconstructive Technologies, Inc., Reno, NV)

Table 6.4

Style 3 buttock implants (Aesthetic and Reconstructive Technologies, Inc., Reno, NV)

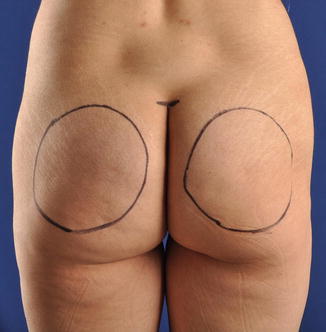

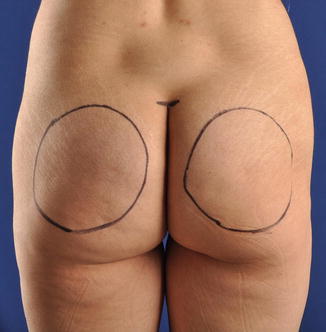

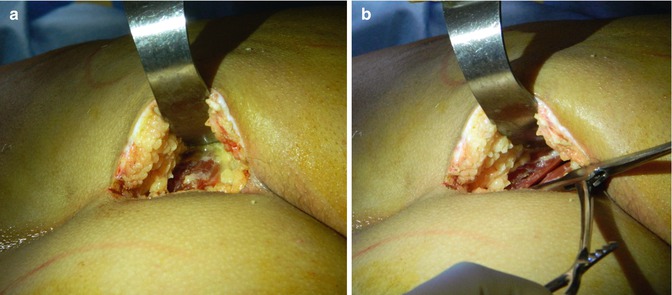

Preoperative Planning and Marking

On the day of the surgery, the patient is met in the preoperative holding area. It is here that the patient’s consent is verified and again risks, benefits, and alternatives are reviewed with the patient. With the patient in the erect position, the proposed site of incision is marked, measuring approximately 5–7 cm. The site of incision should be in the intergluteal cleft, starting at the apex of the cleft and proceeding caudally. This line of incision must be marked in the upright position preoperatively as the intergluteal sulcus loses its definition when the patient is in the prone position during surgery. The area around the anus should be respected, and incisions should not exceed a 5 cm boundary around the anus to avoid injury to the sphincter complex. Once the site of the incision is marked, the site of the proposed implant is marked taking into account the patient’s anatomy and existing deficit along with the desires of the patient (Fig. 6.8). The superior excursion of the buttock is marked with manual manipulation of the buttock in the cephalic direction if liposuction of the hips is to be done. The sacral triangle is marked for reference if liposuction of the sacrum/flanks is to be performed at the same time.

Fig. 6.8

Preoperative markings. Note the superior most horizontal marking indicating the beginning of the natural intergluteal fold. Just below this line is the starting point for the intergluteal fold incision. The site of the proposed implants is marked preoperatively, taking care to ensure that they are evenly placed away from midline (ruler used to ensure symmetric placement). The outline of the implant helps to control dissection intraoperatively

Operative Technique

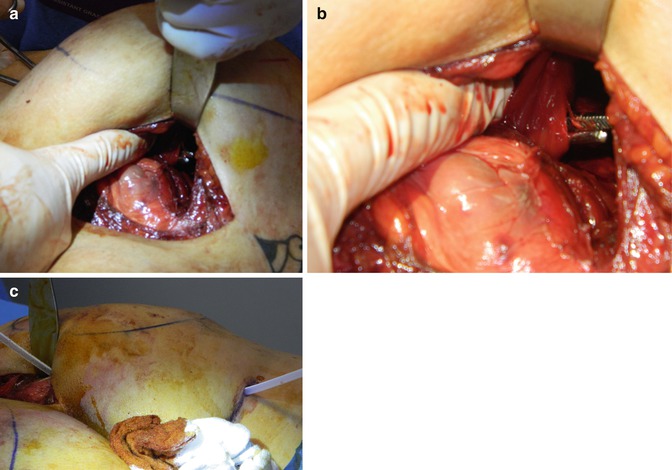

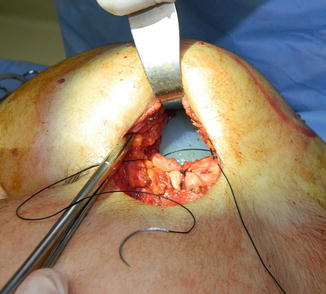

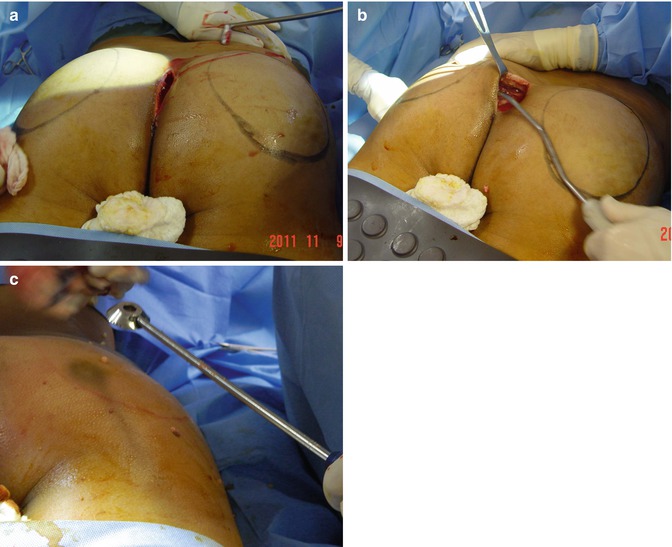

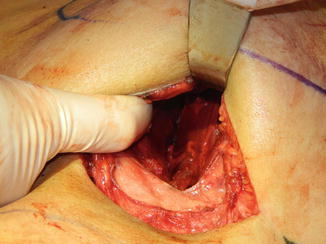

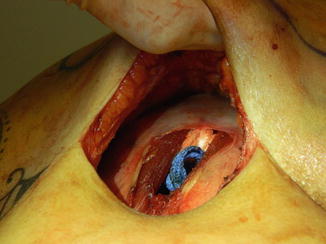

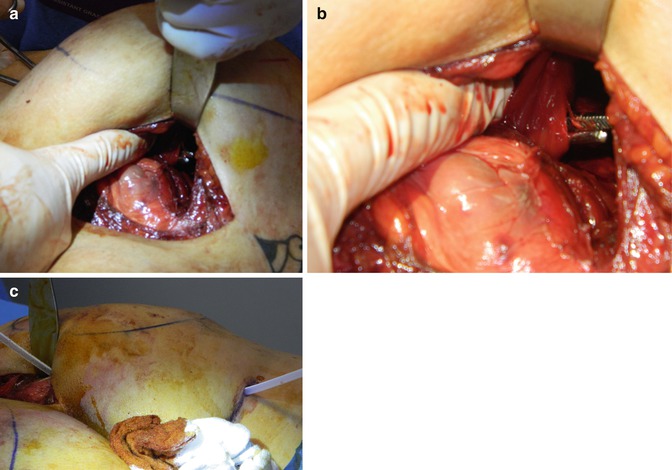

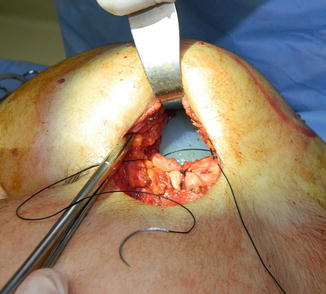

The patient is brought to the operative suite. Anesthesia is administered. The patient is then placed in the prone position. The buttocks and perianal region are prepped and draped in sterile fashion. The previously marked incision site in the intergluteal cleft is incised with a #15 blade scalpel, taking care not to violate the 5-cm safe zone proximal to the anus (Fig. 6.9). Dissection is carried through the subcutaneous tissues using electrocautery, using hooks in the skin to provide adequate visualization (Figs. 6.10 and 6.11). The incision is carried down to the level of the presacral fascia, making sure to maintain the presacral fascia intact as the closure will utilize this fascia as an anchor to recreate the intergluteal sulcus. Dissection is carried laterally to the gluteal fascia (Fig. 6.12). Dissection is carried laterally for approximately 3–4 cm to better expose the gluteal fascia. At a point found to be in the midsection of the gluteus maximus muscle, the gluteus is split in line with its fibers using a large Kelly clamp to achieve a plane below the gluteus maximus muscle (Fig. 6.12). The opening in the gluteus maximus muscle is then extended using electrocautery to create a 6–7 cm defect in the muscle. A spatula dissector and hockey stick dissector, along with finger dissection, are used to further develop this plane, in line with the proposed site of implant placement (Figs. 6.13 and 6.14). The pocket is created in such a way that the gluteus maximus adequately covers the position of the implant in the medial, lateral, and superficial levels. The gluteus medius and minimus then create the floor of the implant pocket (Fig. 6.15). When considering dissection of a buttock augmentation procedure, the medial extent of dissection should respect the sacral triangle. Care is also taken to minimize dissection in the lower third of the buttock which is the support zone of the buttock and supports the weight of the body when sitting. A key point for the novice surgeon at this stage is that one should err on the side of a tight pocket to minimize the risk of over-dissection and increased potential for implant migration that comes with too loose a pocket for the implant. The pocket is then packed with peroxide-soaked sponges, and attention is turned to the contralateral side for similar dissection (Fig. 6.16). Once all dissection has been completed, implant pockets are evaluated for hemostasis. Hemostasis is achieved as necessary with electrocautery. Next, the pocket is irrigated with an antibiotic solution containing Betadine, normal saline, 80 mg gentamicin, and 1 g of Ancef (if the patient is not penicillin allergic). The irrigant is then suctioned out. Ten milliliters of 0.5 % Marcaine is instilled into the pocket to allow for postoperative pain control. Drains are placed via stab incisions in the infragluteal fold using a #15 blade scalpel. Jackson-Pratt drains are then introduced into the pocket and laid into the base of the pocket and secured with 3-0 Nylon suture (Fig. 6.17). The appropriately selected gluteal implant is folded in half (like a taco) and introduced through the incision in the gluteus maximus (Fig. 6.18). The implant is placed in the contralateral side in the similar fashion. Symmetry is then assessed. Once this is deemed to be satisfactory, closure is begun. A 0-Prolene suture (or permanent suture of surgeon’s preference) is then used in interrupted fashion to close the gluteus muscle and fascia over the implant (Fig. 6.19). Once the implant has been fully covered, the intergluteal incision is closed in layers. First, 2-0 Vicryl suture is used to reapproximate the deep subcutaneous tissues and deep dermis to the presacral fascia to recreate the gluteal cleft. 3-0 Vicryl is used as necessary to fully approximate the dermis. 3-0 silk sutures in interrupted fashion are used to close the skin. The patient’s wound is dressed with Neosporin and absorbent pads. The patient is then placed in a compression garment. Anesthesia is discontinued and the patient is taken to the postanesthesia care unit (PACU).

Fig. 6.9

Incision in the intergluteal fold

Fig. 6.10

Hooks placed in the skin to aid in dissection of the subcutaneous plane, taking care to preserve the presacral fascia which will be used at closure

Fig. 6.11

Dissection through the subcutaneous tissue using electrocautery

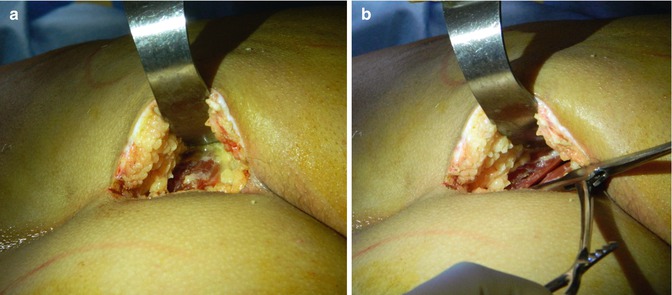

Fig. 6.12

(a) Subcutaneous tissue has been dissected away from underlying muscle, exposing the gluteus muscle. (b) Gluteus maximus muscle is split in its midportion in line with its fibers using a Kelly clamp

Fig. 6.13

Initial dissection of the intermuscular plane using blunt finger dissection

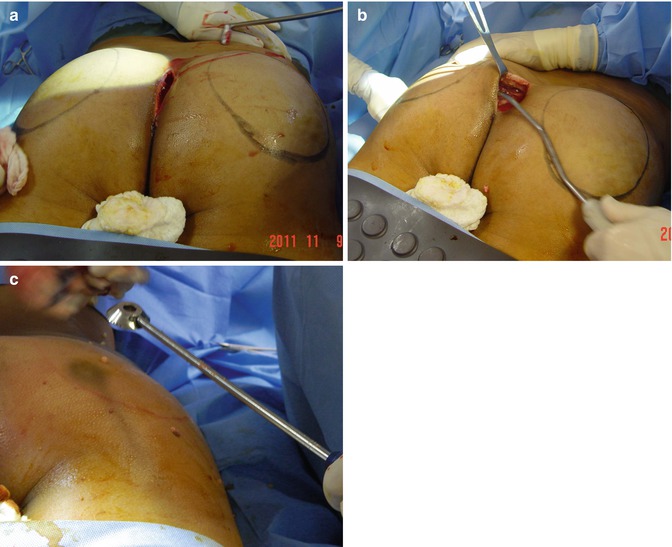

Fig. 6.14

(a) Dissection of the intermuscular plane using a hockey stick dissector. (b) Dissection of the pocket using a spatula dissector. (c) A serrated dissector may be used if there are resistant strands of gluteus muscle that need to be freed to accommodate the implant

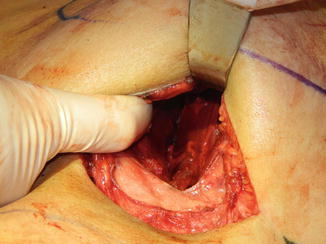

Fig. 6.15

Dissection of the intergluteal plane has been completed. The subcutaneous tissues and gluteus maximus are elevated demonstrating the underlying gluteus medius muscle with transversely directed fibers

Fig. 6.16

Lap sponges in position in the intermuscular plane

Fig. 6.17

(a) Drain placement via a stab incision in the infragluteal fold. (b) Close-up view of Kelly clamp being extended into the intermuscular pocket with the tip of the Kelly spread to accept the drain. (c) Drain in position with exit in the infragluteal fold

Fig. 6.18

Left side augmented with surgeon now returning to the right side for removal of packs and placement of right gluteal implant

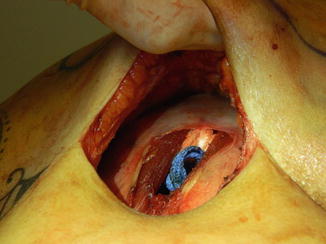

Fig. 6.19

Closure of gluteus maximus muscle over the underlying implant using permanent suture

Postoperative Care/Instructions

Postoperatively the patient may begin ambulating starting on the evening of the procedure. They may shower POD 2, making sure to keep the dressings clean. The buttock region is dried and antibiotic ointment is applied in a thin layer. Patients are then allowed to begin light activity at week 2 and full unrestricted activity at weeks 4–6. Patients are asked to wear an elastic compression garment for 4 weeks postoperatively to prevent dead space, thereby helping to reduce the risk of seroma formation. The legs are to be elevated as much as possible to allow for better lymphatic/venous drainage. Narcotic analgesics are prescribed along with muscle relaxants (diazepam 5 mg every 8 h as needed for spasm) to assist with postoperative pain. Patients are placed on broad-spectrum antibiotics for 7 days. The authors’ preference is to use ciprofloxacin 500 mg BID for its broad coverage, both gram positive and gram negative. For 2 weeks postoperatively, the patient is asked to sleep on their abdomen or side and avoid direct pressure to the buttocks. After 2 weeks, the patient is cleared to sleep on their buttocks and sit on their new bottom side with the intention of slowly stretching the newly forming scar capsule. In the early postoperative period, patients may sit on their bottom side but favoring a “bird on a perch” position with the majority of bodily weight being focused on the posterior thigh region rather than directly on the midportion of the buttocks.

Complications

In performing buttock augmentation, there is a host of complications that can arise (Table 6.5).

Table 6.5

Potential complications of buttock augmentation

|

Potential complications of buttock augmentation surgery

|

|---|

|

Infection

|

|

Seroma

|

|

Hematoma

|

|

Asymmetry

|

|

Implant visibility

|

|

Implant bottoming out/double-bubble deformity

|

|

Implant rupture

|

|

Hypertrophic scarring

|

|

Hyperpigmentation of the scar

|

|

Capsular contracture

|

|

Wound dehiscence

|

|

Nerve injury (permanent or temporary, motor or sensory)

|

|

Pulmonary embolism

|

|

Compartment syndrome

|

Infection

Infection, either superficial or deep, is a possibility in hip/lateral thigh augmentation surgery. There is a reported infection rate of between 1.4 and 5 % in gluteal augmentation surgery, including both superficial and deep infections [15, 30, 31]. The most likely culprits would be Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis, relatively common skin flora. However, gram-negative infections are also possible secondary to the close proximity to the anal canal. Prior to making incision, standard practice should be the administration of 2 g of Ancef IV (or 300 mg IV clindamycin in a penicillin- or cephalosporin-allergic patient). During the procedure, irrigation of the pocket with a standard antibiotic solution containing normal saline, Betadine, Ancef, and gentamicin should be performed. During surgery, a Betadine-soaked gauze is secured over the anus to prevent contamination. Postoperatively, a 7–10-day regimen of oral antibiotics covering normal skin flora along with gram-negative organisms should be administered. The authors’ standard practice is administration of ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days postoperatively. If a deep infection occurs, the standard of practice is removal of the implant, closure, and possible reimplantation in 3–6 months. There are reports in other forms of implant surgery (breast surgery) that conservative management and implant salvage are possible. This should be left to the discretion of the surgeon and performed with careful counseling of the patient. There are reports of late postoperative gluteal infections after augmentation gluteoplasty, but these are quite rare and typically relate to some trauma to the area [32–34]. These delayed infections are typically managed with drainage of the abscess, implant removal, and antibiotics.

Seroma

Seromas are statistically the most common complication occurring in implant surgeries. They typically present as new onset pain, swelling, or asymmetry. The treatment of choice remains percutaneous aspiration. This complication is best prevented with patient compliance with compression garments for 1 month and proper implant placement at the time of surgery, thereby minimizing dead space. In larger studies, such as those by Vergara and Gonzalez Ulloa, the seroma rate for intramuscular augmentations is reported to be between 4 and 10 % [14, 15, 20, 30]. Other large volume studies such as those by Senderoff [30], evaluating 200 consecutive augmentation cases, report seroma rates as high as 28 %. Seromas are best prevented with drain use in the implant pocket. The authors’ standard practice is to leave Jackson-Pratt drains in place until drainage is less than 30 mL/24 h period for 48 consecutive hours.

Occasionally, patients will present with recurrent seromas that are recalcitrant to drainage. If this is the case, a discussion must be had with the patient regarding possible implant removal. Some patients, however, wish to do everything they can to maintain their implant. In this case, the patient does run the risk of having tissue thinning of the buttock due to the constant pressure of the underlying fluid and implant. In one such case, a 26-year-old female underwent buttock augmentation with style 3, size 7 implants and suffered from persistent seromas for 1.5 months that were aspirated in sterile fashion using an 18-gauge needle. After 1.5–2 months, she was noted to have skin thinning in the lower pole of the buttock (dependent) and presented with an exposed implant on the left side (Fig. 6.20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree