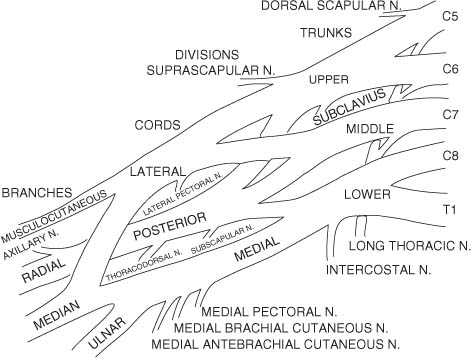

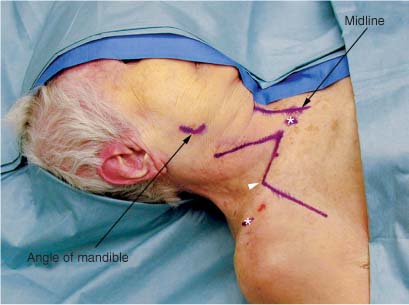

1 The brachial plexus is formed by the ventral primary rami of C5 to T1. It provides innervation to the muscles and skin of the upper extremity. Less often C4 contributes a branch to C5 (referred to as a prefixed plexus) and T2 contributes a branch to T1 (referred to as a postfixed plexus).1 The spinal nerves of the plexus emerge from the neural foramina of the spinal column and travel between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. They descend over the first rib, posterior to the clavicle. The dorsal rami, which are not part of the brachial plexus, supply the muscles and skin of the dorsal neck. In the lower part of the posterior cervical triangle, just distal to the lateral border of the anterior and middle scalene muscles, the C5 and C6 spinal nerves unite to form the upper trunk. Prior to this union, C5 gives off the dorsal scapular nerve to the rhomboids and a branch to the phrenic nerve. The C5 spinal nerve, along with the C6 and C7 spinal nerves, give off contributions to the long thoracic nerve to the serratus anterior muscle. The C7 spinal nerve continues on as the middle trunk. The C8 and T1 spinal nerves unite to form the lower trunk. The upper trunk gives off the suprascapular nerve to the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles as well as the nerve to the subclavius muscle. The brachial plexus trunks lie in the posterior triangle of the neck behind the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The trunks lie deep to (in an anterior to posterior direction) the skin, the platysma muscle, and the fascial carpet of the posterior triangle. Each trunk then divides into anterior and posterior divisions. The anterior divisions of the upper and middle trunks form the lateral cord. The anterior division of the lower trunk continues on as the medial cord. The posterior divisions of all three trunks converge to form the posterior cord. These divisions are found at the level of the clavicle, whereas the cords are found in the infraclavicular space. The cords appear just distal to the clavicle, below the tendinous insertion of the pectoralis minor muscle. They are named according to their spatial relationship to the axillary artery. The lateral cord gives off the lateral pectoral nerve and then terminates as the musculocutaneous nerve and the lateral contribution to the median nerve. The medial cord gives off the medial pectoral, medial brachial cutaneous, and medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves, and then terminates as the ulnar nerve and the medial contribution to the median nerve. The posterior cord gives off the thoracodorsal and subscapular nerves and then terminates as the axillary and radial nerves. Although many variations have been reported, true anomalies of this basic anatomy are rare.2 From the lateral cord the musculocutaneous nerve innervates the biceps and the brachialis muscles. From the posterior cord the radial nerve continues on to innervate the triceps, brachioradialis, and extensor carpi radialis longus muscles. The radial nerve finally gives off the posterior interosseous nerve that innervates the supinator, extensor carpi ulnaris, extensor digitorum, abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, and extensor indicis muscles. Also from the posterior cord the axillary nerve goes on to innervate the deltoid muscle. From the lateral and medial cord the median nerve innervates the pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, flexor digitorum superficialis, abductor pollicis brevis, flexor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis, and lumbricales I and II muscles. The median nerve finally gives off the anterior interosseous nerve to innervate the pronator quadratus, flexor digitorum profundus I and II, and the flexor pollicis longus muscles. From the medial cord the ulnar nerve innervates the flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor digitorum profundus III and IV, adductor pollicis, flexor pollicis brevis, palmar interossei, dorsal interossei, lumbricales III and IV, and the hypothenar muscles. The drawing in Figure 1-1 presents an overview of brachial plexus anatomy. FIGURE 1-1 Drawing of brachial plexus anatomy. Exposure of the brachial plexus anteriorly may be divided into the supraclavicular and infraclavicular approach. Posteriorly the brachial plexus may be exposed from a posterior subscapular approach.3 When working anteriorly the supra- and infraclavicular approaches can be combined for the full exposure of the plexus or tailored to expose the desired area of the plexus. The supraclavicular portion of the approach exposes the roots, trunks, and the proximal portion of the divisions. The infraclavicular portion of the approach exposes the distal portion of the divisions, the cords, and the terminal branches of the brachial plexus. For an anterior approach to the brachial plexus, the patient is placed in the supine position with a bolster or towel between the shoulder blades to obtain a small amount of neck extension. The head is placed in a slight amount of extension and turned 45 degrees toward the contralateral side. The arm is placed abducted on an arm board. If grafting is anticipated, both lower extremities below the knee are sterilely prepped and draped to allow for sural nerve harvesting. If other sources in the upper extremity such as medial brachial or antebrachial cutaneous nerves are to be used for grafting, then the entire arm should be prepped. Positioning should allow the surgeon to work from superior to the clavicle as well as inferior to it in an unobstructed manner. The arm board should be mobile enough to also allow the surgeon to abduct or adduct the arm at the shoulder as necessary. The incision follows the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid. Begin at the angle of the jaw and follow the border of the muscle inferiorly to the clavicle. It is easiest to palpate and draw out the posterior border of the muscle prior to turning the head to the contralateral direction. This should be done before prepping and draping the patient to facilitate easier visualization of all pertinent landmarks. Once at the clavicle the incision turns laterally and follows the superior border of the clavicle out to the lateral third of the bone. If the exposure is to be combined with the infraclavicular approach, the incision crosses the clavicle between its middle and lateral third portions and continues onto the anterior chest wall (Fig. 1-2). The skin should be infiltrated with a vasoconstrictive agent such as lidocaine 1% with epinephrine in a 1:100,000 concentration prior to incision. The skin is divided, exposing the platysma muscle (Fig. 1-3). The platysma muscle is then divided (Fig. 1-4). The skin, along with the platysma, is then raised and retracted (Fig. 1-5). The plane immediately subadjacent to the platysma is an avascular one and easily dissected bloodlessly. The operator should also be aware that the spinal accessory nerve lies close to the apex of the incision superiorly and care should be taken to protect this nerve. The external jugular vein, which crosses the field obliquely, is ligated and excised. The clavicular (“cleido”) portion of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is removed from the clavicle with the electrocautery. The sternocleidomastoid muscle is then retracted medially (Fig. 1-6). NOTE: Retraction in most nerve surgery is done with self-retaining retractors. Blunt-tipped retractors are preferred so as to avoid a sharp injury to the nerve from an improperly placed retractor. However, when a self-retaining retractor is not useful, a silk suture may be placed through the structure to be retracted and the suture then clamped to the drapes. Clearing the thin layer of fat just posterior to the sternocleidomastoid reveals the tendon of the omohyoid muscle, and if medial enough, the internal jugular vein (Fig. 1-7). The omohyoid is then either retracted4–6 or divided and then retracted (Fig. 1-8). If the muscle is divided, it is useful to tag the ends with silk suture. This suture may then be used both for retraction during the case and for reapproximation at the completion of the case. The supraclavicular fat pad, immediately posterior to the omohyoid, is then dissected free in a lateral direction (Fig. 1-9). This fat should be preserved for use at the completion of the case to refill the supraclavicular fossa. Preserving this fat allows for a less hollowed out, cosmetically superior appearance to the supraclavicular area.7 Furthermore, the fat serves as a protective layer over any nerve grafting that may have occurred. After the fat pad and the omohyoid are retracted, the anterior scalene muscle is then visible medially under a thin layer of fat that is also then removed. The phrenic nerve lies on the anterior scalene muscle surface (Fig. 1-10). This nerve should be identified and protected (Fig. 1-11). NOTE: In cases of severe brachial plexus trauma, the phrenic nerve may be completely encased in scar and indistinguishable from the fascia of the anterior scalene muscle. If it is not identifiable visually, the area can be given a low (0.5 mV) direct electrical stimulation, which causes a diaphragmatic contraction that can be appreciated by the surgeon’s direct palpation of the diaphragm beneath the rib cage or by the deflection on the anesthesiologist’s CO2 monitor (Figure 1-12). The phrenic is then traced superiorly until it joins the C5 spinal nerve (Fig. 1-13). The C6 spinal nerve is then deep and slightly inferior to the C5 spinal nerve (Fig. 1-14). The combination of the C5 spinal nerve and the C6 spinal nerve forms the upper trunk (Fig. 1-15). The C7 spinal nerve is located just inferior and deep to the C6 root (Fig. 1-16). The C7 spinal nerve forms the middle trunk. The lower spinal nerves and trunks course in a more horizontal direction in distinction to the upper spinal nerves and trunks, which have a more oblique course.8 The lower trunk is then identified (Fig. 1-17). The C8 and T1 spinal nerves are then identified (Fig. 1-18). To visualize the lower spinal nerves more easily, the anterior scalene muscle may be resected. If this is done, the phrenic nerve, which usually lies atop the muscle, as well as the internal jugular vein, which lies medial to it, must be protected. The lower spinal nerves may also be partially obscured by the subclavian artery as it arcs rostrally (Fig. 1-19). Care must be taken to avoid vascular injury to this large, important vessel. Often, especially in the distorted anatomy seen with brachial plexus trauma, final identification of the lower spinal nerves and trunk must be delayed until identifying the medial cord in the infraclavicular plexus approach and tracing it proximally. The trunks, when identified, are then traced out distally until reaching the divisions. As the upper trunk is traced distally, the suprascapular nerve to the infraspinatus and supraspinatus muscles are identified (Fig. 1-20). With the completion of this identification, attention then turns to the infraclavicular plexus and approach.

BRACHIAL PLEXUS

ANATOMY

POSITIONING AND SURGICAL EXPOSURE

Supraclavicular

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Brachial Plexus

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree