, Paul N. Chugay1 and Melvin A. Shiffman2

(1)

Long Beach, CA, USA

(2)

Tustin, CA, USA

Abstract

The authors focus on the treatment of biceps hypoplasia. There is a discussion on the basic anatomy of the region, the preoperative marking of the patient, and operative procedure. There is a description of the postoperative care and potential postoperative complications. Observed complications are described as well as the management of those complications. Special attention will be made in discussing compartment syndrome as the gravest of all complications and the management of compartment syndrome in upper extremity augmentation.

Introduction

Over the years, there has been an increase in the number of males seeking out cosmetic surgery. Recent statistics by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons show an increase of 5 % in men seeking out cosmetic surgery procedures when comparing 2011–2012 [1]. Despite attempts at betterment through physical activity and weight training, some men are unable to achieve their desired outward appearance. For that reason, they present to a cosmetic surgeon for a host of procedures aimed at improving body contour. Liposuction has ranked in the top five procedures performed by men for the past several years [1, 2]. While being fat is definitely something that men wish to avoid, it seems that more males are concerned with having a muscular physique which is believed to be associated with attractiveness to the female sex and a sign of masculinity [3]. The advent of body implants for augmentation of various muscle groups has brought patients to surgeons’ offices seeking augmentation when other measures have failed to give them a more “sculpted” physique [4].

Fascination with the muscular male dates back to antiquity. Stars of the silver screen such as Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, and Jason Statham have popularized the muscular and well-built man. Male action figures and Playgirl centerfolds have further demonstrated the obsession with a muscular physique, causing many males to critique themselves and become dissatisfied with their outward appearance [5, 6]. Augmentation of the biceps is one of the muscle groups that lends itself to immediate results with significant improvement in the contour of the male form, with a potential to improve a male’s overall impression of himself. Herein, we will discuss the background of the procedure, the operative technique, and common complications seen in bicipital augmentation.

Body Dissatisfaction in Males

Researchers commonly use the concept of an “Adonis Complex” to explain the wide array of secret body image concerns experienced by males. These concerns include everything from body dissatisfaction to muscle dysmorphia (MD), a subtype of body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) found mostly in males, that causes males with either normal or muscular physiques to believe their body is too small or inadequately muscular [5, 7, 8]. Body dissatisfaction has received a lot of attention in male body image research, partly due to its prevalence in Western society. Pope et al. [8] estimated there to be over 50 million males in the United States who were dissatisfied with their muscularity at the beginning of the twenty-first century. This number has most likely risen with various media outlets creating even more unrealistic images of the ideal male body, including the modern and hyper-muscular GI Joe [5] and the lean and muscular Playgirl centerfold model [7]. Pope even went so far as to extrapolate the muscularity of action figures to human size and determined that today’s GI Joe figure would be just as unattainable to boys as the Barbie doll is for girls [3]. In its most extreme case, muscularity concerns can lead to muscle dysmorphia, which is commonly viewed as the equivalent of anorexia nervosa in females [9]. While females with anorexia perceive themselves to be too big, males with MD perceive themselves to be too small. Ironically, many males with MD are more muscular than their normal counterparts. Males with MD are ashamed and embarrassed of their perceived inadequate muscularity and think about it constantly. Many males with MD also report mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and substance abuse.

Muscle dissatisfaction is associated with numerous psychological problems including depression, low self-esteem, and overall low life satisfaction [9]. The desire for a muscular body has led patients down the road of behavioral problems, disordered eating, use of prohormones, and anabolic steroid use. Although not without its complications, biceps augmentation stands to be an alternative for males who seek to have a more muscular physique and avoids the use of drugs and extreme dieting that are well documented to have deleterious physical and psychological side effects [3, 5, 9].

History of the Procedure

Biceps augmentation was initially used by surgeons to help in the reconstruction of soft tissue defects of the upper extremity left by significant trauma or post-oncologic surgery [10]. While it does not add to the patient’s use of the arm, the use of a silastic implant does provide “gratifying cosmetic results” that are durable, leaving surgeons an option for maintaining symmetry of the body. Hodgkinson [11] further added to the literature on the use of solid silicone implants for restoration of symmetry and addition of volume to traumatized extremities. In his article from 2006, he discusses the use of silicone implants to add volume to the upper extremity after ruptures of triceps and biceps muscles and in cases of axillary nerve injury that showed degeneration of the deltoid muscle.

From its initial introduction for reconstructive purposes, the primary author produced research in the area of biceps augmentation for cosmetic purposes in early 2006 [12]. The actual use of biceps implants for cosmetic reasons was begun in 2004, by the primary author, when a 32-year-old recreational body builder presented with a complaint of an underdeveloped biceps region. By the time of publication in 2006, the author had completed a total of 12 augmentations in the submuscular plane, below the biceps brachii muscle. This was followed by a retrospective review of 94 cases in 2009, which further evaluated the procedure and its potential risks and complications [13]. All procedures were performed via an incision in the axilla and placement of the implant in the submuscular plane. In the primary author’s experience, greater risks for complications were possible with placement of the implant under the muscle. With placement solely beneath the fascia, the improved contour was similarly noted but without the increased risk of damage to vital neurovascular structures. For that reason, the primary author’s standard practice at this time is use of a subfascial approach for implant placement, rather than the submuscular plane. In 2010, Dini and Ferreria [14] evaluated the size of the short head of the biceps muscle and devised an implant based on these dimensions, measuring 20 cm in length, 3 cm in width, and 1.7 cm in height made out of silicone envelope filled with silicone gel. The implant is introduced via an incision in the axilla and placed in a subfascial plane. In 2012, Abadesso and Serra [15] published their work on 32 cases of biceps augmentation for improving the cosmetic appearance of the arms. Their report includes augmentation brachioplasty performed for increase in brachial volume in 16 patients (50 %), to correct sagging skin in 9 (28.1 %), and to improve the appearance of the arm after bariatric surgery in 5 (15.6 %). While the primary author prefers the use of an axillary incision for bicipital augmentation, Abadesso and Serra use a 4 cm long S-shaped incision in the middle of the arm. They then place calf implants into the submuscular plane to achieve the desired augmentation. In patients that require more volume, they combine solid silicone elastomer implants with cohesive gel silicone implants using a 3-0 nylon suture to stack the implants on top of one another.

Indications

Initially, biceps augmentation was introduced as a means to treating asymmetries in the arm region left due to congenital anomalies, trauma producing atrophy of muscles in the upper extremity, and in those patients who suffered volume deficits secondary to trauma or post-oncologic surgery. Biceps augmentation, for purely aesthetic reasons, is indicated for the patient who has hypoplasia in the area of the biceps muscle. It can be used in the patient who has a condition from birth resulting in hypoplasia or may be applied to a patient who is unsuccessful in achieving the desired volume in the region of the biceps, despite aggressive weight training (e.g., body builders).

Contraindications

While not every male presenting for biceps augmentation suffers from muscle dysmorphia, the surgeon must be aware of this and take it into consideration when considering a patient for muscle augmentation surgery. A patient who seems unrealistic in the goals of his surgery should be turned away.

Limitations

In any initial biceps augmentation, patients are instructed on the fact that they can achieve an augmentation of approximately 1 inch in added circumference of the arm. Larger augmentations may require a second operation with larger, custom implants. Also, patients are instructed that while biceps and triceps augmentations can be performed, it is safer to separate this into two separate surgeries to avoid the risk of compartment syndrome in the upper extremity.

Relevant Anatomy

The technique described herein is ideal in that it avoids major neurovascular structures in the upper extremity. However, for completeness sake some of the basic anatomy that is pertinent to the discussion of biceps augmentation will be reviewed.

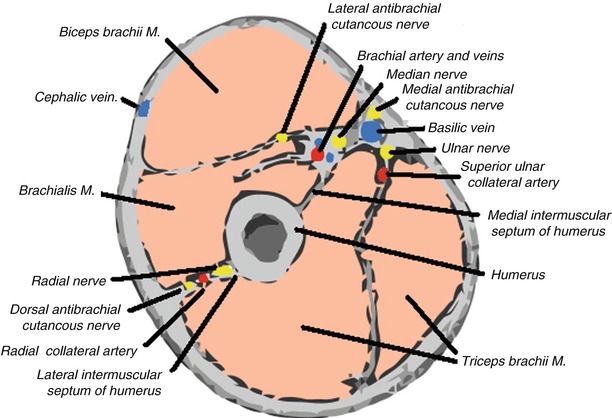

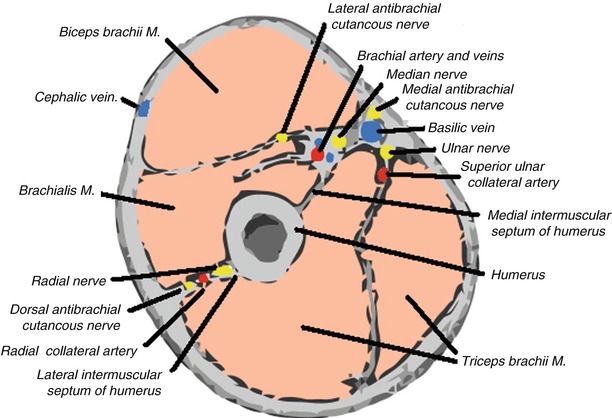

An axial section through the mid arm shows much of the relevant anatomy for biceps augmentation (Fig. 3.1). Two distinct muscular compartments (anterior and posterior) exist in the upper arm and are separated by the medial and lateral intermuscular septa and humerus [16, 17]. The medial and lateral intermuscular septa arise from the humerus and insert into the brachial fascia, which covers the superficial muscles of the anterior compartment. The anterior compartment is composed of the biceps brachii, brachialis, and coracobrachialis. The posterior compartment is composed of the triceps muscle. The biceps brachii is a long muscle consisting of two heads and functions to flex the elbow and supinate the forearm (Fig. 3.2). The short head arises by a thick flattened tendon from the apex of the coracoid process. The long head arises from the supraglenoid tuberosity at the upper margin of the glenoid cavity. Each tendon is then succeeded by an elongated muscular belly. The two bellies are closely adherent but then unite into a single flattened tendon about 7.5 cm proximal to the elbow joint. This tendon then inserts onto the radius. The fascia overlying the biceps is often referred to as the deep fascia of the arm and is a continuation of the fascia covering the deltoid and pectoralis major. As mentioned previously, it gives off the strong intermuscular septa to the medial and lateral aspects that form the distinction between anterior and posterior compartments of the arm [16].

Fig. 3.1

Axial cross section of arm showing humerus with medial and lateral intermuscular septa that separate anterior from posterior compartments of the arm. The anterior compartment is composed of the biceps brachii, brachialis, and coracobrachialis. The posterior compartment is composed of the triceps muscle. Major neurovascular structures are primarily localized to the medial aspect of the arm

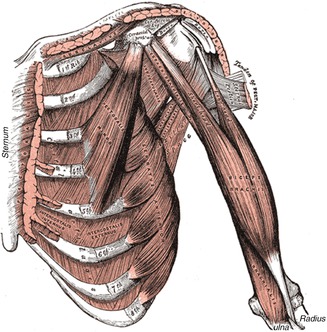

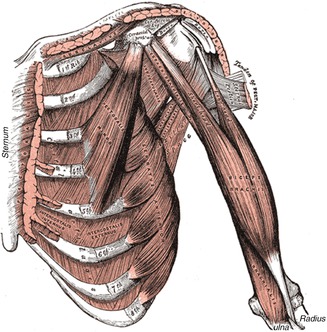

Fig. 3.2

Biceps brachii with long and short heads

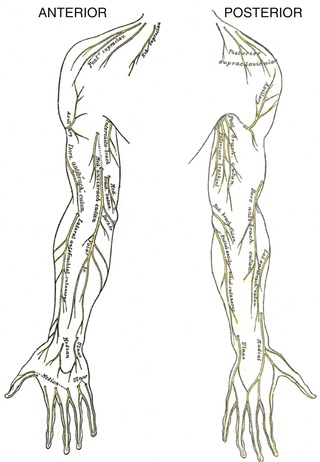

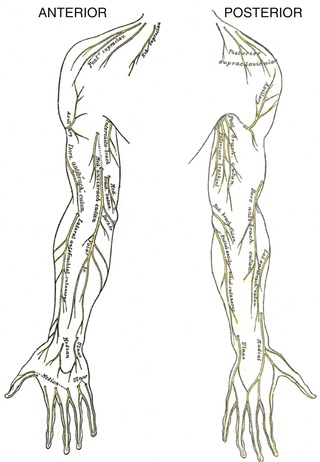

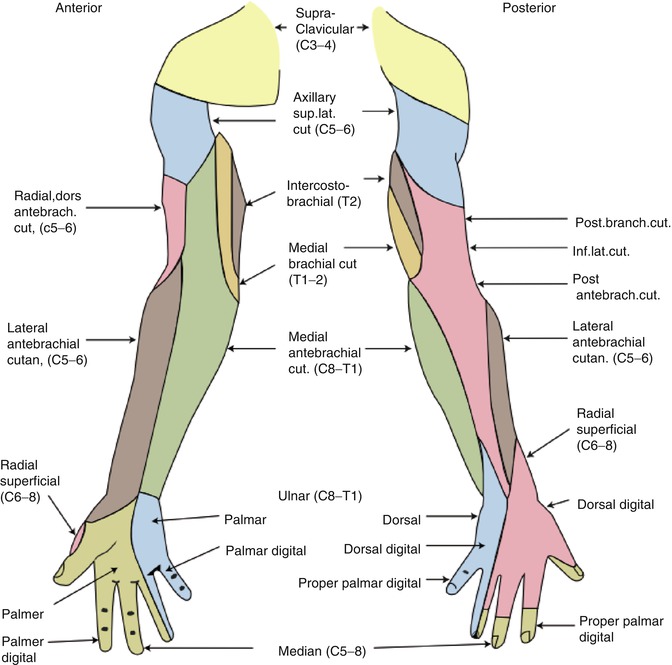

One of the structures most at risk for injury is the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve (Fig. 3.3). This nerve is a continuation of the musculocutaneous nerve and serves as one of the primary sources of sensory innervation to the skin of the forearm in the lateral aspect (Fig. 3.4). It runs along the undersurface of the biceps and can be injured with submuscular placement of the biceps implant. The nerve continues on the undersurface of the biceps brachii muscle until it emerges just lateral to the biceps tendon, 2–4 cm above the elbow crease. For this reason, it is possible to have a compression injury along the course of the nerve when the implant is placed in the submuscular plane and exerts direct pressure on the nerve [18, 19]. The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve is derived from the medial cord of the brachial plexus and serves as a major contributor of sensory nerves of the medial aspect of the forearm (Fig. 3.5). It is more medial in the dissection of the upper arm and is spared in the typical dissection for biceps augmentation, both subfascial and submuscular [18].

Fig. 3.3

Nerve distribution in the upper extremities (dorsal and ventral views)

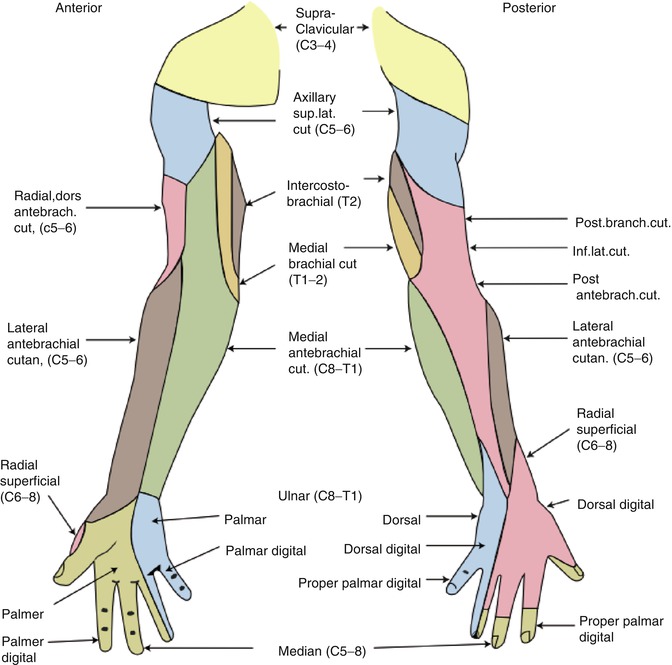

Fig. 3.4

Sensory dermatomes of the nerves of the upper extremity

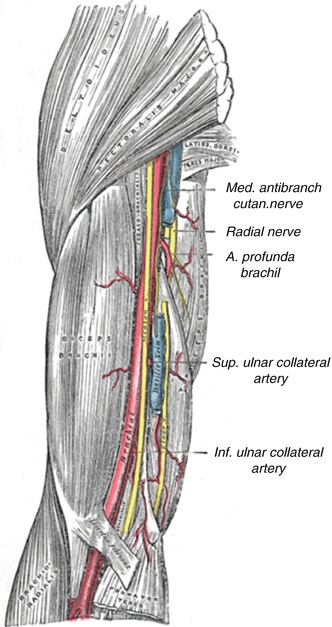

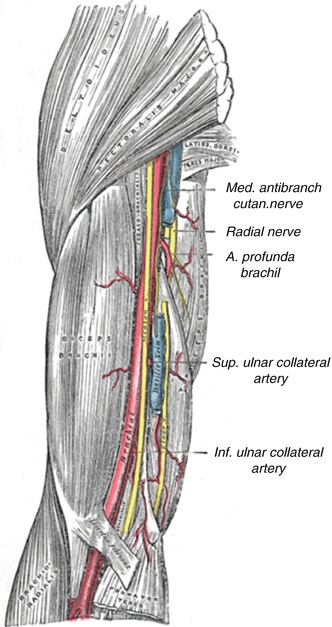

Fig. 3.5

Anatomic location of medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. Note close proximity of medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve to major neurovascular structures on the medial aspect of the arm, high near the initial entry point for surgery (axilla)

The cephalic vein is a major superficial vein of the upper extremity along with the basilic vein. The cephalic vein crosses superficial to the musculocutaneous nerve and ascends in the groove along the lateral border of the biceps brachii, leaving it open to injury with aggressive dissection of the subfascial pocket in the lateral aspect. The basilic vein also plays a major role in the superficial venous drainage of the upper extremity. It runs upward along the medial border of the biceps brachii, perforates the deep fascia slightly below the middle of the arm, and, ascending on the medial side of the brachial artery to the lower border of the teres major, continues onward as the axillary vein. This vessel is spared in a typical subfascial biceps augmentation but may be injured with aggressive medial dissection in the submuscular approach to biceps augmentation.

The brachial artery (a continuation of the axillary artery) commences at the lower margin of the tendon of the teres major, and, passing down the arm, ends about 1 cm below the bend of the elbow, where it divides into the radial and ulnar arteries. At first, the brachial artery lies medial to the humerus; however, it gradually moves in front of the bone as it runs down the arm, and at the bend of the elbow, it lies midway between its two epicondyles. The brachial artery is the major supplier of blood flow to the upper extremities. Because this artery is superficial throughout its entire extent, being covered in front by the integument and the superficial and deep fascia, great care should be taken to preserve its integrity. Risk of injury comes with submuscular approaches to biceps augmentation as very medial dissection can injure the neurovascular bundle.

Consultation/Implant Selection

The consultation begins with a thorough medical history on the patient. Special attention is taken to ask specifically about trauma to the extremity, history of vascular insufficiency which may put blood flow at risk, history of venous insufficiency or arm swelling, and any history of nerve damage or sensory deficits as may be seen in patients with diabetes mellitus. Also, patients with histories of nerve entrapment disorders should be asked about the current state of those nerves and any long-term sequelae. At the time of consultation, the patient is asked what specifically about their arm bothers them as it may be necessary to combine muscle augmentation surgery with adjunct procedures such as liposculpture or brachioplasty to achieve the patient’s goals. Preoperative goals are assessed at this point. A patient who has unrealistic expectations and is unable to comply with the strict postoperative instructions is deemed a poor candidate for augmentation. Patients who have congenital anomalies, significant size disparities between the two arms, or bilateral hypoplasia are informed that several surgeries may be required to attain symmetry and achieve the augmentation they desire. Patients are also asked about their current level of activity and muscle building history, taking care to inform the patient of the need to take at least 1 month of time to recover before resuming any vigorous arm building regimens.

After completion of the history, the patient’s arms are evaluated. First, symmetry of the two sides is assessed and any disparity is brought to the attention of the patient. Although the majority of patients present with a preexisting asymmetry of the arms, not many patients note the difference and this can be a source of medicolegal matters in the future. The physician then evaluates the quality of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle. A person who has very thin tissues or significant hypoplasia of the biceps may not be able to adequately accommodate a large implant. Also, a person with thin tissues may have to be counseled about the possible need for a submuscular placement of the prosthesis. This should be accompanied by a discussion of the increased risks associated with biceps augmentation in the submuscular plane.

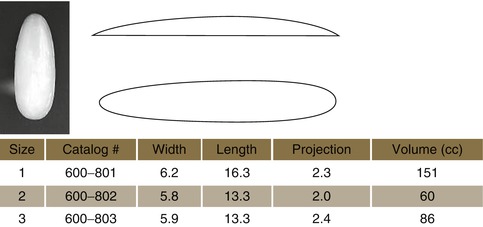

Next, the patient’s arms are measured in circumference at the midportion of the arm, with the patient in flexed and neutral positions. These measurements are primarily used in the postoperative period to demonstrate the results of augmentation. Another measurement is taken with the patient flexing their biceps muscle. The proximal point of the muscle belly is palpated and marked as is the distal portion of the muscle belly and then measured. Having this second measurement allows one to assess the maximum length of implant that can be accommodated in the biceps region. Next, the width of the muscle belly is measured from its medial to lateral extent while the patient’s muscle is flexed. Based on these latter measurements, the surgeon can choose the implant that would best suit the patient’s body habitus (Fig. 3.6).

Fig. 3.6

Biceps implant (style 8, size 1)

Available Implants (Table 3.1)

Table 3.1

Available biceps implants (Aesthetic and Reconstructive Technologies, Inc., Reno, NV)

Preoperative Planning and Marking

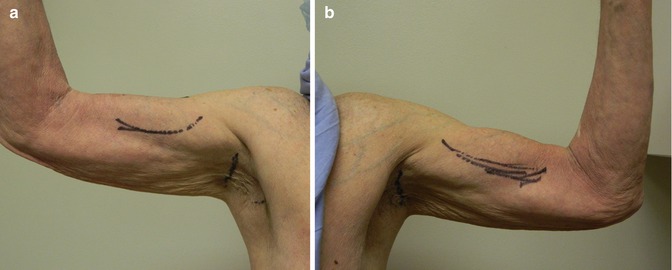

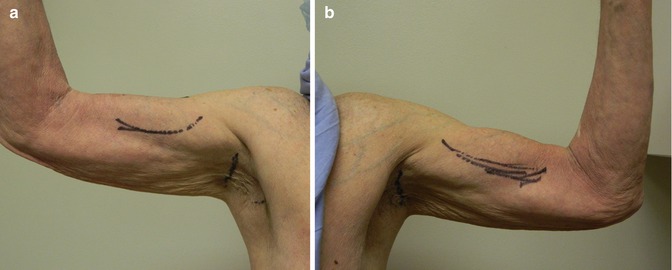

The biceps contour is marked out with a surgical marking pen, taking special care to also mark the apex of the biceps. A marking is then made in the axillary region for the initial incision in the axilla (Fig. 3.7).

Fig. 3.7

Preoperative markings for biceps augmentation taking care to mark borders of biceps muscle and axillary incision. (a) Patient’s right arm (b) Patient’s left arm

Operative Technique

Subfascial Placement (Standard)

The incision is made in the axillary region with a number 15 blade, and the skin is dissected out by sharp and blunt dissection (Fig. 3.8). With gentle digital pressure, the tissues are displaced until the bicipital fascia is exposed (Fig. 3.9). The bicipital fascia is then incised with a # 15 blade, and 3-0 nylon stay sutures are placed on each side into the fascia for retraction (Figs. 3.10 and 3.11). A pocket is dissected in the subfascial plane, exposing the biceps muscle fibers. The authors’ standard of practice is to place the implant in a subfascial plane to avoid many of the complications that can arise from damage to neurovascular structures in a submuscular plane. If proceeding with a subfascial approach to augmentation, the surgeon will use a combination of blunt finger dissection and spatula dissection to create a subfascial pocket that encompasses the biceps muscle as previously marked (Fig. 3.12). Care is taken not to over-dissect the pocket as a pocket that is over-dissected can lead to greater problems with implant migration and possible seroma formation. The pocket is then packed with a lap sponge and the same procedure is repeated on the contralateral side. At this point the packs are removed and hemostasis is achieved with electrocautery as needed. The pocket is irrigated with a solution containing saline, Betadine, 1 g of cefazolin, and 80 mg of gentamicin. This is aspirated from the pocket. Then, 10 mL of 0.5 % Marcaine is instilled into the pocket for postoperative analgesia. A custom Chugay bicipital implant (AART Corp) is placed into the subfascial pocket (Fig. 3.13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree