Chapter 41 Benign melanocytic tumors

2. What is a nevus?

Derived from the Latin term meaning “spot” or “blemish,” nevus was originally used to describe a congenital lesion or birthmark (mother’s mark). In modern usage, the term describes a cutaneous hamartoma, or benign proliferation of cells. However, when the term is used without a descriptive adjective, it usually refers to a melanocytic nevus. Examples of nevi used in the context of a birthmark are epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous.

3. Are there different types of melanocytic nevi?

Yes. Melanocytic nevi can be classified according to their histology based on 1) location of the nevus cells (e.g., junctional, compound, or intradermal nevi), 2) cytologic atypia (e.g., atypical [dysplastic] nevi, and 3) morphology and architectural arrangement of nevus cells (e.g., Spitz and spindle cell nevi). Melanocytic nevi can also be classified based on their appearance (e.g., halo nevi or blue nevi). In addition, there are congenital melanocytic and acquired nevi.

4. How do melanocytes get to the skin?

Melanocytes arise from the cranial and truncal neural crest cells in embryonic life. The development of melanocytes from neural crest cells, as well as their ability to migrate, is dependent upon interactions between specific receptors and extracellular ligands, including endothelin 3 and the endothelin B receptors, α–melanocyte stimulating hormone and the melanocortin-1 receptor stem cell factor and its receptor KIT, each of which induce expression of the microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF). MITF is the most critical regulator of pigment cell development and survival. Bone morphogenic protein (BMP) is a negative regulator of this process.

5. Explain the natural developmental history of melanocytic nevi.

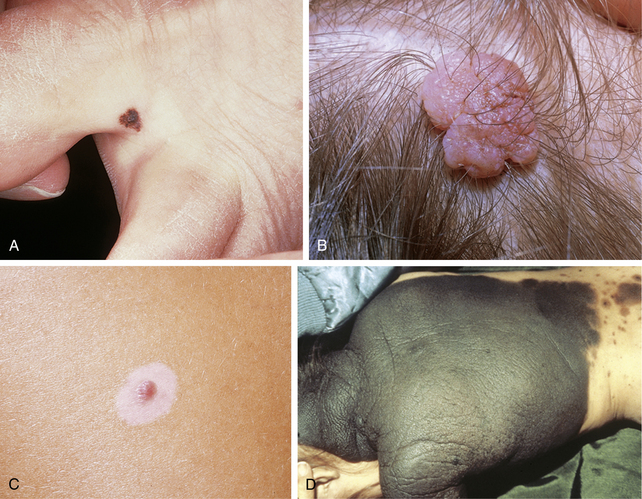

Melanocytic nevus cells are derived from melanocytes and differ from normal epidermal melanocytes in a number of ways. They are no longer dendritic; they do not distribute melanin to surrounding keratinocytes; and they are less metabolically active. Melanocytic nevi are benign clonal proliferations of cells expressing the melanocytic phenotype, and are thought to be derived from precursor cells that acquire genetic mutations. These mutations are thought to activate proliferative pathways and/or or suppress apoptosis, allowing for the accumulation of melanocytic cells in the skin. The type of nevus that is formed is thought to be dependent upon the specific mutation, as well as local environmental factors. B-Raf mutations are commonly seen in acquired melanocytic nevi. Acquired melanocytic nevi are thought to begin as a proliferation of nevus cells along the dermal–epidermal junction (forming a junctional nevus; Fig. 41-1A). With continued proliferation of nevus cells, they extend from the dermal–epidermal junction into the dermis (forming a compound nevus). The junctional component of the melanocytic nevus may resolve, leaving only an intradermal component (intradermal nevus; Fig. 41-1B). However, it should be stressed that there is debate regarding the direction of nevus growth.

Grichnik J: Melanoma, nevogenesis, and stem cell biology, J Invest Dermatol 128:2365–2380, 2008.

6. What is a halo nevus?

A halo nevus, also known as a Sutton’s nevus or leukoderma acquisitum centrifugum, is a melanocytic nevus with a surrounding well-circumscribed annulus of hypo- or depigmented skin (Fig. 41-1C). Halo nevi can be solitary or multiple and generally affect individuals under the age of 20 years. In general, those patients with halo nevi have an overall increased number of melanocytic nevi. Halo nevi are commonly associated with vitiligo, with ∼20% to 50% of vitiligo patients demonstrating halo nevi. Conversely, ∼15% to 25% of patients with halo nevi have vitiligo. Although both halo nevi and vitiligo may look similar clinically, recent studies strongly suggest that halo nevi and vitiligo have separate pathogenetic mechanisms. Although not completely understood, the pathogenesis of halo nevi is thought to be related to 1) an immune response against antigenically altered nevus cells or 2) a cell-mediated or humoral immune response against nonspecifically altered nevus cells. It is not completely understood whether this represents an abnormal immunologic response or whether the immune system is recognizing an atypical clone of nevomelanocytes.

7. What is a congenital nevus?

A melanocytic nevus that is present at birth. For the purpose of management, any melanocytic nevus that arises during the first year of life is considered “congenital.” Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) are usually characterized as small, large, or giant, although there is no universally accepted definition of these categories. Small CMN are usually defined as being up to 1.5 cm in diameter, large CMN as being between 1.5 and 20 cm in diameter, and giant CMN as being more than 20 cm in diameter. Another scheme for classifying small, large, and giant CMN considers the percentage of the body surface area the lesion covers, or the ease of surgical removal and repair of the resulting surgical defect. Still another classification scheme describes giant CMN as being as large as two of the patient’s palms for lesions on the trunk and extremities, or the size of one palm for lesions on the face or neck (Fig. 41-1D).

8. What is the risk of developing a malignant melanoma in a congenital nevus?

Although there is little agreement about the risk of developing melanoma within a CMN, some general guidelines can be stated. The risk appears to relate to the size of the CMN. A small or medium CMN does not appear to have any significantly greater risk for melanoma than an acquired melanocytic nevus. The best evidence suggests that there is about a 1% to 4% chance of developing melanoma in CMN > 60 cm. The need for removal of congenital nevi is one of the most controversial issues in pediatric dermatology. It should be stressed that surgical removal of the CMN does not decrease their risk for melanoma.

9. What is a blue nevus?

Blue nevi and related melanocytic proliferations (i.e., congenital dermal melanocytoses including Mongolian spot, nevus of Ito and nevus of Ota) are a heterogenous group of congenital and acquired melanocytic lesions that have in common several clinical, histologic, and immunochemical features. They have been termed dermal dendritic melanocytic proliferations, because they are usually composed, at least in part, of dendritic melanocytes within the dermis. The deep dermal location of the pigment-producing cells, and therefore the pigment, causes the lesion to have its blue, black, or gray appearance due to the Tyndall effect (Fig. 41-2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree