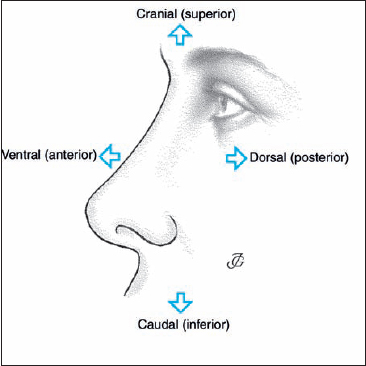

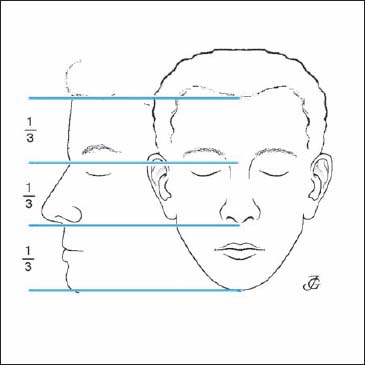

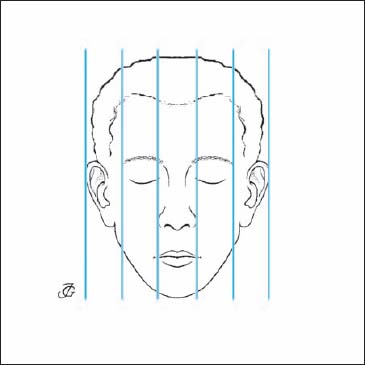

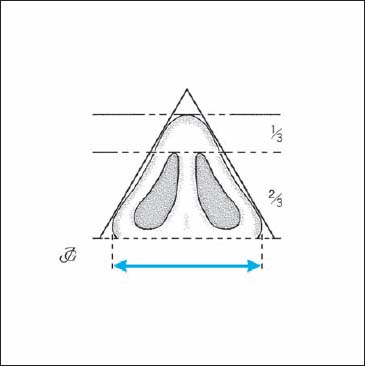

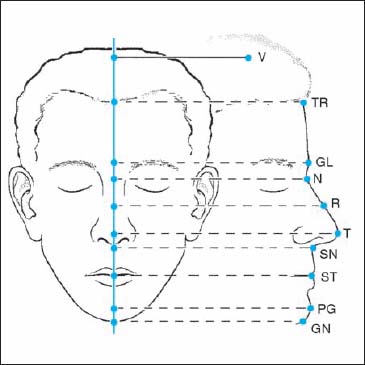

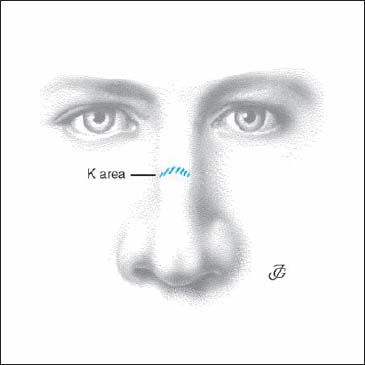

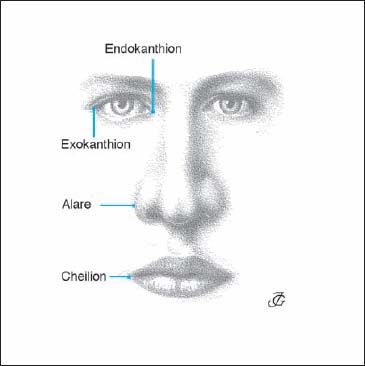

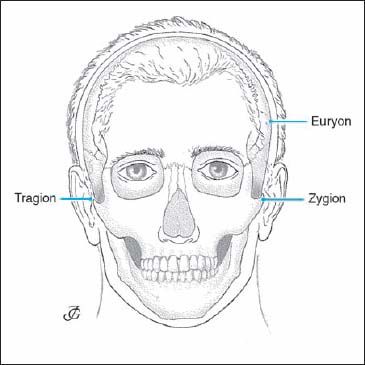

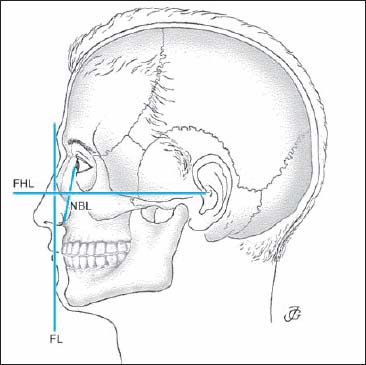

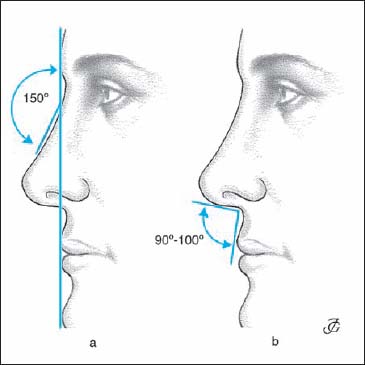

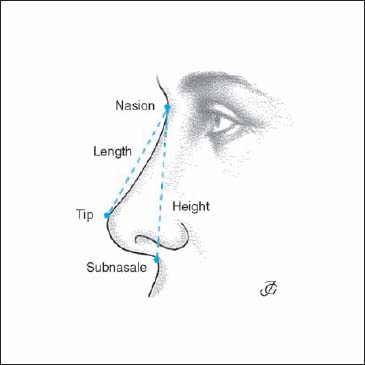

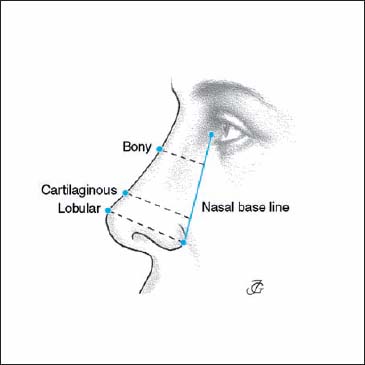

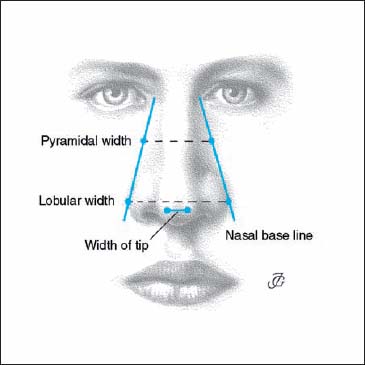

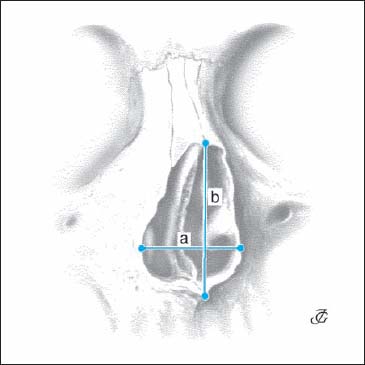

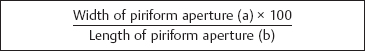

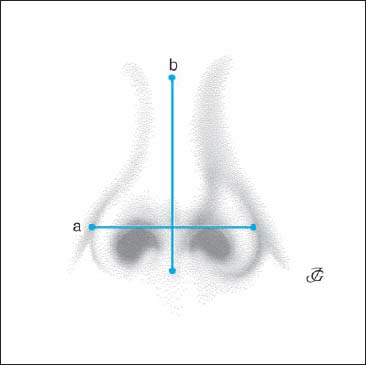

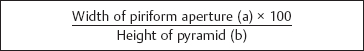

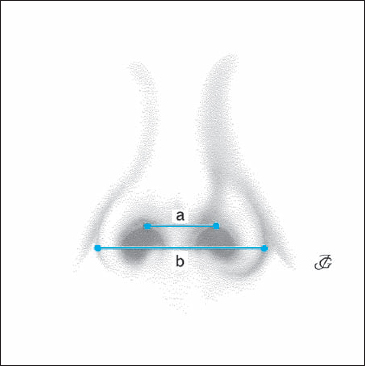

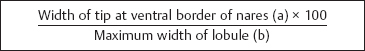

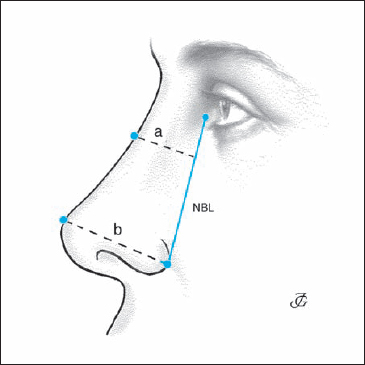

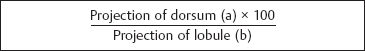

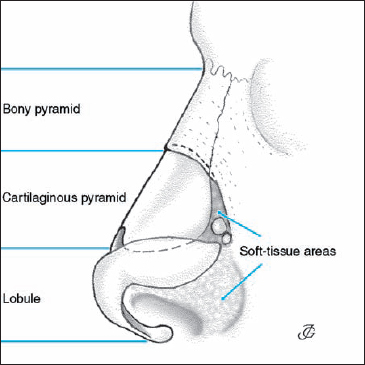

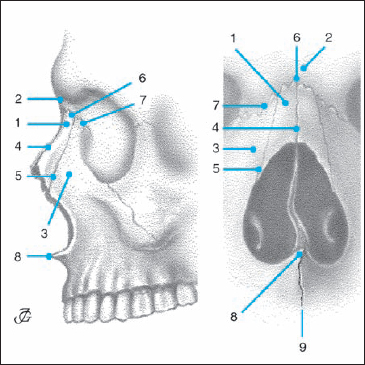

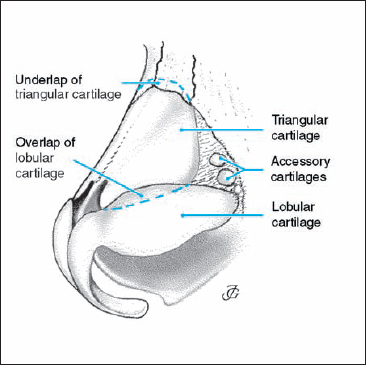

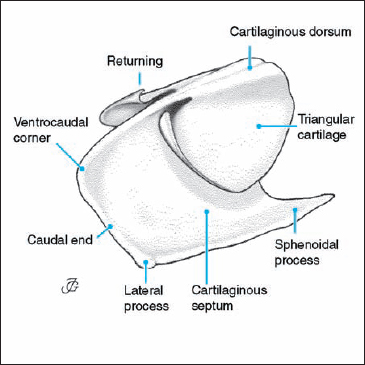

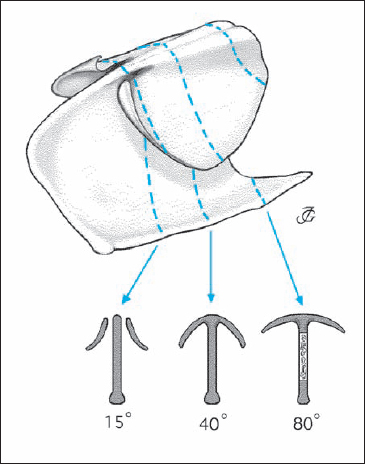

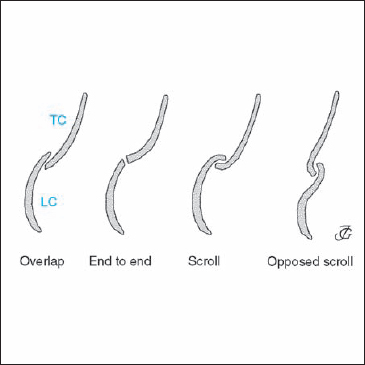

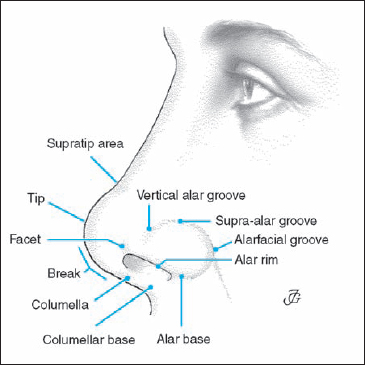

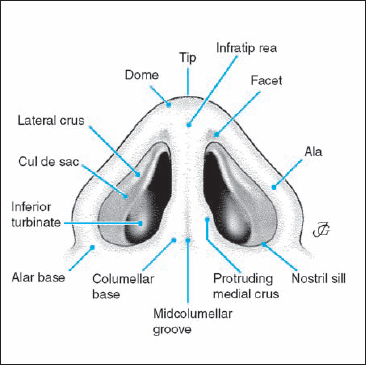

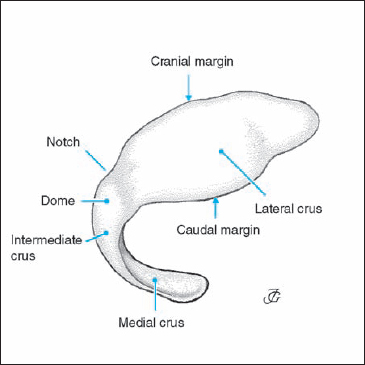

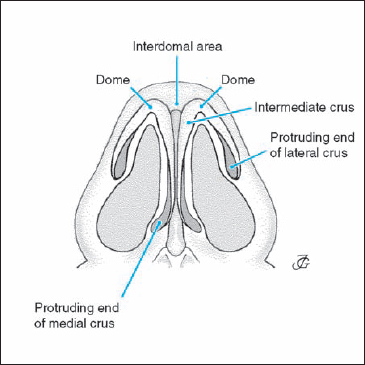

1 Basics Both in diagnosis and surgery, the following terms should be used for orientation (Fig. 1.1): These definitions are to be preferred above others as they are universal and do not change with body position. In the American literature, the term “cephalic” is often used for “cranial.” The human face shows considerable variations in size, form, and proportions. The primary factors involved are race, gender, and age; the secondary factors are growth and trauma. It is therefore difficult to distinguish between normal and abnormal. It is even more difficult—and in principle impossible—to define “the beautiful face.” The concept of beauty has not been consistent through the centuries. The various human civilizations have adhered to different ideals. Even within the same culture, these ideals have changed over time. Our ideas about facial proportions originate in the work of the artists Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528). According to their concept of harmony the human face may be divided into three equal horizontal and five equal vertical parts (Figs. 1.2, 1.3). It may be helpful to draw the horizontal, vertical, and base lines on the photographs of the patient when analyzing the facial proportions and the relationship of the external nose with other parts of the face. Other than as an aid to partitioning, however, the Leonardo–Dürer concept should not be used. First, the concept is not applicable to all races; second, age and gender play a dominant role; and finally, the concept of beauty is highly subjective. In our opinion, the primary responsibility of a rhinosurgeon is to recreate a nose with normal function and normal form. Enhancement of beauty is of secondary importance. Fig. 1.1 Topographic terminology to be used in nasal surgery. Fig. 1.2 Horizontal division of the face into three equal sections Fig. 1.3 Vertical division of the face into five equal sections Fig. 1.4 The height of the upper lip is about half of the distance Gnathion-Stomion. Fig. 1.5 Triangular shape of the lobule. In the Caucasian nose the distance from the lobular base to the upper corner of the nostril is about twice as long as the length of the tip. The face is made up of three equal sections: hairlinenasion = nasion–subnasale = subnasale–pogonion (Figs. 1.2, 1.6). The height of the external nose is equal to that of the forehead and to that of the lower face. This division can be greatly influenced by hair growth, hairstyle, and spectacles. The lower part of the face can be divided into two parts: the upper lip (one-third) and lower lip with chin (two-thirds) (Fig. 1.4). The face can be divided into five equal sections: the nasal section, the two eye sections, and the two lateral sections (Fig. 1.3). When looked at from caudal the nasal lobule forms a triangle. The height and base of this triangle differ according to race, gender, and age (see tip index, p. 6). In the Caucasian race the distance from the lobular base to the upper corner of the nostril (length of the columella) is about twice as long as the length of the tip (Fig. 1.5). When analyzing the face, several anthropometric points may be used. Certain ones are on the skull (bony landmarks) while others are on the skin (clinical points). The following points are important in nasal analysis. Fig. 1.6 The most important midline points of the face and the nose. V = vertex Fig. 1.7 K area or Keystone area. Fig. 1.8 The most important paranasal points. highest point of the head when it is oriented in the Frankfort horizontal plane. midpoint of the frontal hairline. midline elevation above the nasal root at the level of the eyebrows. midpoint of the frontonasal suture. Deepest point at the transition between the forehead and the nose. most caudal point of the intranasal suture. most prominent point of the lobule. midpoint of the nasolabial angle overlying the anterior nasal spine. imaginary point at the crossing of the vertical facial midline and the horizontal labial fissure between the lips. most ventral midpoint of the chin. midpoint of the caudal margin of the chin. The “keystone” or K area is the region where the nasal bones, triangular cartilages, and cartilaginous septum unite. The term was coined by Cottle to emphasize that the nasal vault resembles a Gothic arch closed by a keystone. inner commissure of the eye fissure. outer commissure of the eye fissure. Fig. 1.9 The most important lateral points. most lateral point of the alar curvature. Used to measure the lobular width. the point located at each labial commissure. most prominent lateral point on each side of the skull. most lateral point of the zygomatic arch. notch on the upper margin of the tragus. The most important lines on the head are the Frankfort horizontal line (FHL) and the facial line (FL). They are used both anthropometrically and clinically. A third line that is helpful in surgery is the nasal base line (Fig. 1.10). The FHL is the line on the skull from the inferior orbital margin to the upper margin of the external bony ear canal (tragion). In clinical practice, the line between the inferior orbital margin and the upper border of the tragus is used. The FHL should be horizontal when side-view photographs are taken. The FL is the line from the glabella to the pogonion. It serves as the baseline for calculating the nasofrontal and the nasolabial angle. The FL helps to analyze and define the dimensions of the nasal pyramid in relation to the midface, forehead, and chin. Fig. 1.10 Frankfort horizontal line (FHL), facial line (FL), and nasal base line (NBL). The nasal base line (NBL) is a slightly oblique line on the skin at the nasal base from the medial canthus to the alar facial groove. The prominence (= projection = salience) of the bony and cartilaginous pyramid and the lobule is measured from this line. In performing lateral osteotomies and wedge resections the NBL is used as a line of reference. The following text describes the most important angles in nasal analysis. The nasofrontal angle is the angle between the FL and the line over the dorsum of the bony pyramid (Fig. 1.11a). Its magnitude depends on race and age. In Caucasian adults, it measures about 150°. Both in Asians and Blacks it is larger. The magnitude of the nasofrontal angle has no relation to nasal function. From an aesthetic point of view, a large variation is generally acceptable, reflecting ethnic differences. The nasolabial angle is the angle between the base of the columella (subnasale) and the upper lip (Fig. 1.11b). In Caucasian males, this angle measures 80–90°, in females 90–110°. In Asians and Blacks it is usually larger. The nasolabial angle is to a certain extent related to nasal function. The smaller this angle, the more vertical the inspiratory airstream enters the nose and the higher in the nasal cavity the air will reach. Also, aesthetically the nasolabial angle is considered more important than the nasofrontal angle. Fig. 1.11a Nasofrontal angle. b Nasolabial angle. Fig. 1.12 Height and length of the nose. Fig. 1.13 Prominence of the bony pyramid, cartilaginous pyramid, and lobule. Fig. 1.14 Width of pyramid, lobule, and tip. Height of pyramid: distance between nasion and subnasale (columellar base) (Fig. 1.12). Length of pyramid: distance between nasion and tip (Fig. 1.12). Prominence (projection, salience): ventral projection of the pyramid measured from the NBL (Fig. 1.13). distance between NBL and most prominent part of bony dorsum. distance between most prominent part of cartilaginous dorsum and NBL. distance between tip and NBL at the alar facial groove. Width of pyramid: horizontal dimension of the base of the pyramid and of the tip (Fig. 1.14). distance at the base of the bony cartilaginous pyramid between left and right NBL. distance between the lateral walls of left and right alar cartilages. distance between the two domes. Fig. 1.15 Anatomical nasal index Normal values: Leptorrhine (Caucasian): < 46.9 Platyrrhine (Black): 47.0–50.9 Chamaerrhine (e.g. Asian): 51.0–57.9 (after Knuszmann 1988) Fig. 1.16 Clinical nasal index Normal values: Leptorrhine (Caucasian): 55.0–69.9 Platyrrhine (Black): 70.0–84.9 Chamaerrhine (e.g. Asian): 85.0–99.9 Hyperchamaerrhine (Black): > 100.0 Fig. 1.17 Lobular (tip) index This index is normally about 70. It is smaller in the platyrrhine, Black, and growth-disturbed nose. It is greater in patients with an excessive prominence of the nasal pyramid. The following anatomical and clinical indices may be useful in nasal surgery: The way they are measured is illustrated in Figures 1.15–1.18. Determining nasal indices may be helpful in analyzing nasal abnormalities and assessing the results of surgery (e.g., in shortening the nose, increasing the projection of the tip or the cartilaginous dorsum, and narrowing the lobule). This index is normally about 70. It is smaller in the platyrrhine, Black, and growth-disturbed nose. It is greater in patients with an excessive prominence of the nasal pyramid. This index is usually 55–65. Its clinical value is limited. Fig. 1.19 The four major parts of the external nose: bony pyramid, cartilaginous pyramid, lobule, and soft-tissue areas. The external nose consists of four major parts (Fig. 1.19): The bony pyramid, cartilaginous pyramid, and lobule comprise about one-third of the external nose. Together they form an integrated anatomical–physiological entity. This is the result of the rigid fixation of the cartilaginous vault to the lower margin of the bony pyramid (underlap of 1.0–1.5 mm Fig. 1.21) and the junctions between the lobule and the cartilaginous pyramid, in particular the connection (and overlap) between the lateral crus of the lobular cartilage and the lower margin of the triangular cartilage Fig. 1.21. At four different areas the pyramid consists of soft tissue, allowing a certain amount of mobility Fig. 1.19. The external nasal pyramid is covered (from the outside to the inside) by skin, subcutaneous connective fatty tissue, and muscle fibers. The thickness and extent of these various layers show considerable individual variation. The bony pyramid (or bony vault) is the bony part of the external nose that projects above both NBLs. Its upper midpoint is the depth of the nasofrontal angle or nasion. Its lowest point is the rhinion or K area. The bony pyramid consists of the nasal bones, the nasal spine of the frontal bone (spina nasalis ossis frontalis), and the two frontal processes of the maxilla (Fig. 1.20). The nasal bones are small, oblong, and quadrangular. They are thicker and narrower cranially and thinner and wider caudally. They are attached to each other in the midline by slightly serrated borders that form the internasal suture. Cranially they unite with the nasal part of the frontal bone to form the frontonasal suture. About halfway down the sloping side of the pyramid, their lateral margins meet the frontal process of the maxilla at the frontomaxillary suture. Their inside (dorsal) surface is smooth and forms part of the anteriorwall of the nasal cavity. It has an oblong groove, the ethmoidal sulcus, for the anterior branch of the ethmoidal nerve. The nasal bones often show small perforations (nasal foramina) through which blood vessels penetrate. The frontal processes of the maxillary bones make up the dorsal part of the bony vault. They are thicker than caudally. Lateral osteotomies are usually carried out in this part of the bony vault. 1 = nasal bone 2 = frontal bone (nasal part) 3 = frontal process of maxilla 4 = internasal suture 5 = nasomaxillary suture 6 = frontonasal suture 7 = frontomaxillary suture 8 = anterior nasal spine 9 = intermaxillary suture Fig. 1.21 Bony pyramid, cartilaginous pyramid, lobule, and soft-tissue areas. Fig. 1.22 Septolateral cartilage with reflection of the medial part of the caudal margin of the triangular cartilage. The cartilaginous pyramid or vault is made up by the septolateral cartilage and the two lateral membranous areas with one to three accessory cartilages (Fig. 1.21). The septolateral cartilage (Fig. 1.22) consists of The attachment of the cartilaginous vault to the bony pyramid is rigid. The upper margin of both triangular cartilages underlap the lower margin of the nasal bones by 1–2 mm over a distance of 5–10 mm (Fig. 1.21). See also page 36 and Figures 1.71a, b. The area where the nasal bones, the septal cartilage, and the two triangular cartilages unite is commonly called the keystone or K area (see Fig. 1.7). The cartilaginous vault is a T-shaped construction. Its angle gradually diminishes from about 15° at the lower margin of the triangular cartilage to almost 90° at the K area (Fig. 1.23). See also page 36, 37 and Figures 1.72a, b. In this way a funnel-type construction is created that plays an important role in breathing and conditioning of the inspired air (see p. 47 ff). Fig. 1.24 Most common relationships between the triangular cartilage (TC) and the lobular cartilage (LC). The septal cartilage (cartilaginous septum) rests with its base on a bony pedestal consisting (from ventral to dorsal) of the anterior nasal spine, the premaxilla, and the vomer. Caudally it has a free, somewhat mobile end that is connected to the columella by the membranous septum. Dorsally it is united with the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone. Ventrally it is continuous with the two triangular (or upper lateral) cartilages. Together they make the cartilaginous vault and dorsum. See also page 28, 29 and Figures 1.63a, b and 1.64 a, b. The triangular cartilages (upper lateral cartilages) are continuous with each other and the septal cartilage. Together they constitute the cartilaginous vault. Cranially their margins are underlying and firmly fixed to the caudal margin of the nasal bones. Medially the triangular cartilage is lined by mucosa. It covers the inside of the cartilaginous part of the internal nasal cavity. Dorsally it is connected with the lateral soft-tissue or “hinge” area (see Fig. 1.30). Ventrally it is continuous with the septum in its upper two-thirds, while in its lower third a small cleft with loose connective tissue is found between its medial margin and the septum (medial soft-tissue area). The length of this cleft is variable and related to the length of the nose. The caudal margin of the triangular cartilage is free and protrudes into the vestibule. Its lateral side is covered by skin (the “cul de sac”). The medial third of the caudal margin is usually rotated upward 160°−180°. This is called returning, scrolling, or curling (see Fig. 1.22). The caudal margin of the triangular cartilage moves inward and outward with respiration (valve function). These movements are possible because of its relatively loose fixation to the medial and lateral soft-tissue areas (the cleft and the hinge area, respectively). The reflection of the medial part of the lower margin, on the other hand, increases its rigidity and thus counteracts an easy collapse of the lateral nasal wall at inspiration. The relationship between the triangular cartilage and the lateral crus of the lobular cartilage shows large variations. The most common relationship is a certain overlap of the caudal margin of the triangular cartilage by the cranial margin of the lateral crus of the lobular cartilage. Other relationships that may be found are: “end to end,” “scroll,” and “opposed scroll” (Dion 1978) (Fig. 1.24). In the dense connective tissue that connects the lateral crus to the triangular cartilage, several sesamoid cartilages can be found. They provide both mobility and stability, allowing the intercartilaginous area to act more or less as a joint (see also p. 36, 37 and Fig. 1.72a–c). Fig. 1.25 Lateral view of the lobule with its major anatomical–clinical structures. Fig. 1.26 Base view of the lobule with its main structures.

Surgical Anatomy

Face

Face

Orientation

Proportions

The Western Standard

Horizontal Division

Vertical Division

Lobular Base Division

Points

Midline Points (Fig. 1.6)

Keystone or K Area (Clinical) (Fig. 1.7)

Paranasal Points (Fig. 1.8)

Lateral Points (Fig. 1.9)

Lines

Frankfort Horizontal Line

Facial Line

Nasal Base Line

Angles

Nasofrontal Angle

Nasolabial Angle

Dimensions

Nasal Indices

External Nose (External Pyramid)

External Nose (External Pyramid)

Bony pyramid

Cartilaginous Pyramid

| Nomenclature of triangular cartilage | |

| Nomina anatomica (NA): | cartilago nasi lateralis (lateral nasal cartilage) |

| North America: | upper lateral cartilage (ULC) |

| Germany: | Seitenknorpel |

| France: | cartilage laterale |

| This book: | triangular cartilage (TC) |

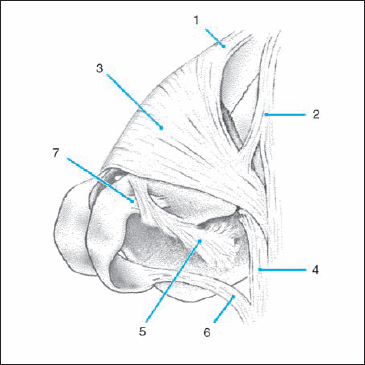

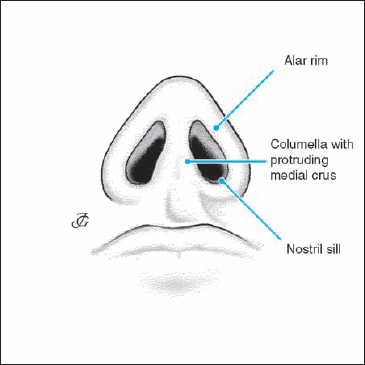

Lobule

The lobule is the mobile lower third of the external nasal pyramid. It is made up of two lobular cartilages, muscle fibers, subcutaneous connective and fatty tissue, and a relatively thick skin with sebaceous glands. The major structures of the lobule are illustrated in Figures 1.25 and 1.26.

Tip

The tip (apex nasi) consists of the two domes, the interdomal connective-tissue fibers, and the overlying skin.

- Supratip area: a slight depression just cranial to the tip (“the dip before the tip”).

- Tip-defining point: most prominent area of the dome of the lobular cartilage. The tip is made up of the two tip-defining points.

- Infratip area: part of the lobule anterior (ventral) to the nostrils and the columella

Alae

The alae are the mobile lateral walls of the lobule that are made up of the lateral crura of the lobular cartilage and the overlying muscles and skin.

- Alar rim: caudal margin of the ala. Together with the columella and the nostril sill, it forms the nostril (ostium externum or naris).

- Alar base (alar foot): area of attachment of the ala to the face.

- Facet: flat area at the ventrocaudal part of the ala corresponding to the caudal lobular notch.

- Vertical alar groove: vertical groove or depression of the ala just medial to the dome.

- Supra-alar groove or crease: horizontal groove just above the cranial margin of the lateral crus.

- Alar facial groove: fold at the alar base between the ala and face.

Columella

The columella is the midline structure running from the upper part of the lobule to the upper lip, consisting of the medial crura of the lobular cartilage. The columella is more or less broadened due to the lateral (outward) curvature of the end of the medial crura.

- Columellar break: slight bent of the lower margin of the columella at the level of the upper (dorsal) margin of the nostril.

- Midcolumellar groove: vertical groove in the skin between the medial crura.

Nostril (Naris, Ostium Externum)

The orifices of the lobule are usually called the nostrils or nares. They are bounded by the columella, lower alar rim, and the nostril sill.

- Nostril sill: inferior rim of the nostril.

Fig. 1.27 Left lobular cartilage with its anatomical parts.

Fig. 1.28 Lobular cartilages in relation to the tip, alae, and columella.

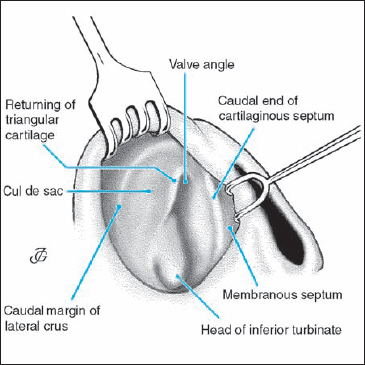

Vestibul

The vestibule is the skin-covered cavity between the nostril and the valve area. Its upper part lateral to the protruding caudal margin of the triangular cartilage is a blind-ending pouch commonly called the “cul de sac.” The caudal part of the vestibule is provided with hairs (vibrissae) that offer some protection to the entrance of the respiratory tract against insects, etc.

| Nomenclature of lobular cartilage | |

| Nomina anatomica (NA): | cartilago alaris major greater alar cartilage |

| North American: | lower lateral cartilage alar cartilage |

| German: | Flügelknorpel |

| This book: | lobular cartilage |

Lobular Cartilages

The lobular cartilages are horseshoe-shaped cartilages that support the structured anatomy of the whole lobule. They determine the position and form of the tip, the alae, and the columella as well as the configuration of the nares and vestibules.

It is common in surgical practice (but not in the discipline of anatomy) to divide the lobular cartilage into three or four parts (Fig. 1.27):

- medial crus

- intermediate crus

- dome

- lateral crus.

Medial Crus

The medial crus is the slightly bent medial part of the lobular cartilage. It supports the columella, nares, and tip. Its length and width vary greatly. Its end (ventral part) protrudes slightly into the vestibule, broadening the columellar base (Fig. 1.28). The space between the medial crura is filled with loose connective tissue. There are no crossing fibers between the two crura. See page 38, 39 and Figures 1.74a,b.

Intermediate Crus

The intermediate crus may be defined as the transitional segment between the medial crus and the dome. It cannot always be clearly identified as a separate part of the lobular cartilage. Many authors therefore do not recognize it as a separate structure.

Dome

The dome is the strongly bent part between the medial and lateral crus. Its curvature varies greatly from 80° (ballooning type) to 10° (narrow type). Its cranial border is often notched. The two domes together make the nasal tip. It has been suggested that the two domes are connected by a bundle of midline crossing fibers, an interdomal ligament or Pitanguy’s ligament. In a histological study, we were unable to confirm the presence of horizontal, midline-crossing fibers (see p. 38 and Figs. 1.73 a–c).

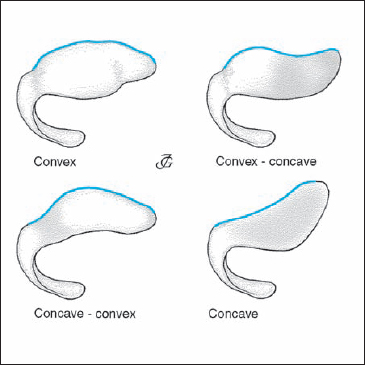

Lateral Crus

The lateral crus is the lateral extension of the lobular cartilage supporting the ala. Its shape may be convex, convex–concave, concave–convex, concave, and flat (Fig. 1.29). The convex type is the most frequent. Its length (mediolateral dimension) varies from 16 to 30 mm, its maximal height (craniocaudal dimension) from 6 to 16 mm. The distance of its caudal margin to the alar rim increases in ventrodorsal direction.

Fig. 1.29 Most common shapes of the lateral crus of the lobular cartilage.

Fig. 1.30 The soft-tissue areas.

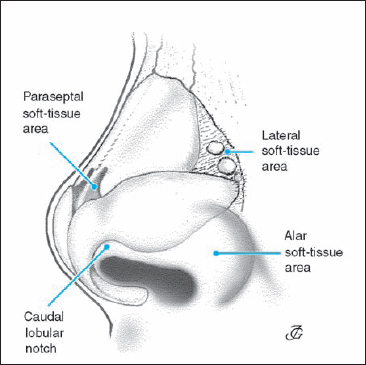

Soft-Tissue Areas

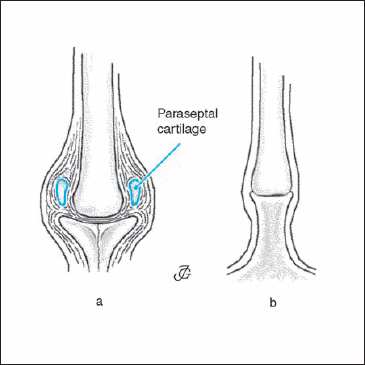

The external nasal pyramid has four soft-tissue areas. Unfortunately, there is considerable confusion about their terminology in the literature. We suggest using the following nomenclature (Fig. 1.30):

- paraseptal cleft or paraseptal soft-tissue area

- lateral soft-tissue area or hinge area

- caudal lobular notch

- alar soft-tissue area.

The paraseptal cleft (paraseptal soft-tissue area) is a narrow triangular opening between the cartilaginous septum and the lower third of the medial margin of the triangular cartilage, filled with loose connective tissue. It allows the outward and inward movement of the lower part of the triangular cartilage during respiration.

The lateral soft-tissue area (hinge area) is a more or less triangular soft-tissue area between the lateral margin of the triangular cartilage and the lateral wall of the piriform aperture. It consists of relatively dense connective-tissue fibers with two to three accessory cartilages. It allows outward and inward movements of the triangular cartilages (and valve) and alae. It is therefore also called the hinge area.

The caudal lobular notch is found medially at the lower margin of the lateral crus. It does not seem to have any special functional significance. It deserves special attention and needs to be carefully preserved during lobular surgery.

The alar soft-tissue area is the most dorsal and caudal part of the ala inferior to the lateral crus of the lobular cartilage.

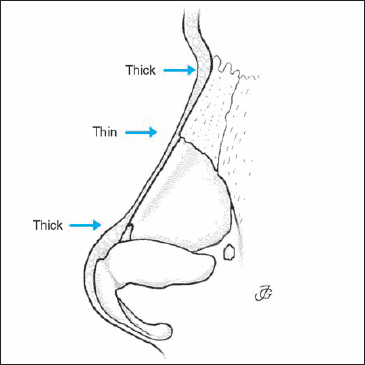

Skin and Connective, Muscular, and Fatty Tissues Overlying the External Nose

The external nasal pyramid is covered from outside to inside by:

- an epidermis of varying thickness and a dermis with sebaceous glands and hair follicles,

- a connective-tissue layer of varying thickness containing the vascular and nerve supply,

- a variable amount of fatty tissue,

- a musculofascial layer, a fibromuscular layer, a deep fatty layer, and a periosteal or perichondrial layer that is attached to the bone or cartilage.

Nowadays, many authors like to speak of a superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS), consisting of a superficial fatty layer, a fibromuscular layer, a deep fatty layer, a longitudinal fibrous layer, and an intercrural ligament (Letourneau and Daniel 1988). We do not follow this distinction between the various layers as they show considerable differences at the various parts of the external nasal pyramid. See also page 36, 37 and Figures 1.72 a–c.

The bony pyramid is covered in its upper part by relatively thick skin with a considerable amount of subcutaneous connective tissue and muscle fibers (procerus). In its lower part, the nasal bones are covered by a rather thin skin, a thin layer of loose connective tissue, and some transverse muscle fibers (transverse part of nasalis) (Fig. 1.31).

Fig. 1.31 Thickness of the skin and subcutaneous tissues overlying the external pyramid.

The loose subcutaneous layer allows movement of the skin over the bone while offering protection against trauma and pain from pressure. This is illustrated by patients in whom this layer has not been preserved during surgery; they often complain of tenderness in this region.

The cartilaginous pyramid is covered by a somewhat thicker layer of soft tissue. The skin has a larger number of sebaceous glands and hair follicles. The muscle fiber layer is thicker as well. See also page 36, 37 and Figures 1.72a, b.

The lobule has a thick covering consisting of epidermis, dermis with hair follicles and numerous sebaceous glands, fat, connective tissue with the vascular supply, lymph vessels and nerves, muscle fibers and fascia (musculo-aponeurotic layer), and areolar tissue.

The thickness and quality of the skin depend on a great number of factors including gender, age, and climatological influences. The subcutaneous connective-tissue layer is relatively thick, especially between the cartilages. A variable amount of fatty tissue can be found in the midline just above the interdomal area and laterally. See also page 39 and Figures 1.76a, b.

Four different muscles can be distinguished. The fibers run from the lobular cartilage into the skin, adding to the rigidity of the lateral lobular wall or ala. As a result, the lobular skin is not freely movable over the lobular cartilage.

Fig. 1.32 The seven most important nasal muscles superimposed on a 3D computerized reconstruction (artist’s impression) of the bony and cartilaginous structures in a 45-year-old male (from Bruintjes et al., 1996).

1. Procerus muscle. 2. Levator labii alaeque nasi muscle. 3. Transverse part of nasalis muscle. 4. Alar part of nasalis muscle. 5. Dilatator naris muscle. 6. Depressor septi muscle 7. Apicis nasi muscle.

Musculature

The external nasal pyramid is almost completely covered by a thin layer of musculature. There is no consensus on the number of muscles that can be distinguished and no agreement on their names.

Terminologia Anatomica (1990) recognizes five nasal muscles. Most anatomical and rhinosurgical textbooks mention seven or nine, however.

All nasal muscles have a mimic function. Some of them also play a role in breathing and provide stability for the lateral nasal wall. In this section we follow the recent work of Bruintjes et al. (1996) who recognized seven different nasal muscles (Fig. 1.32).

The procerus muscle is an impaired layer of muscle fibers. They originate in the nasofrontal suture area, fan in a caudal direction (hence its alternative name pyramidalis), and insert in the skin over the bony pyramid. These muscle fibers produce transverse wrinkling of the skin at the root of the nose. Some fibers may reach as low as the ala and thus may assist in elevating the ala and dilating the nostril.

The levator labii superioris alaeque nasi muscle arises from the frontal process of the maxilla. It has a small medial part that inserts into the perichondrium of the lateral crus. It can thus act as a dilatator of the nostril and elevator of the lateral lobular wall.

The nasalis muscle (transverse part) originates in the maxilla above the canine tooth and the skin over the nasolabial fold. It runs to the midline of the nasal dorsum. It acts as a stabilizer of the lateral nasal wall. See also page 38 and Figures 1.73 b, c.

Fig. 1.33 Five areas of the internal nose according to Cottle (1961).

The nasalis muscle (alar part) also originates in the maxilla but at a point somewhat more medial than the transverse part. It inserts at the lateral and lower margin of the ala. These fibers may draw the ala laterally and dilate the valve area. This muscle is the most important stabilizer of the lateral nasal wall.

The dilatator naris arises from the lateral crus and superimposing alar skin and inserts into the skin of the nasolabial groove. Not all authors accept this view, however. The muscle acts together with the alar part of the nasalis muscle as alar abductors and openers of the nostril.

The depressor septi muscle originates in the maxilla above the incisive tooth, together with the fibers of the alar part of the nasal muscle, and inserts in the medial crus. It pulls the membranous septum down, widening the nostril.

The apicis nasi muscle is a very small muscle lying on the lower medial part of the lateral crus. Its function is a matter of debate.

Internal Nose

Internal Nose

Anatomically, embryologically, and physiologically we distinguish:

- two nasal cavities (two noses);

- three nasal passages on both sides: the lower, middle, and upper meatus; and

- three nasal openings on both sides: the nostril (external ostium, naris), the valve area (internal ostium), and the choana.

Anatomical–Physiological Subdivision of the Nasal Organ

Over the years several suggestions have been made to divide the differents parts of the nose on the basis of anatomical, physiological, and/or pathological differences.

External vs Internal Nose

The oldest subdivision is the distincton between the external and the internal nose: the external nose, specific to humans, is the prominent bony, cartilaginous, and soft-tissue pyramid in the middle of the face, while the internal nose with its mucosa, turbinates, and septum is the nasal organ proper.

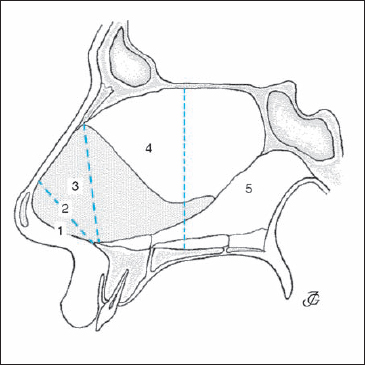

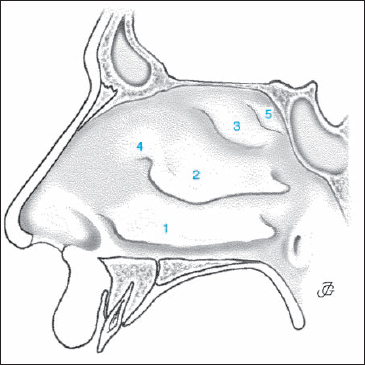

Five-Area Division of Cottle

For the purpose of diagnosis and documentation, as well as to correlate pathology with symptomatology, Cottle (1961) proposed to divide the internal nasal cavity into five areas (Fig. 1.33).

Area 1: nostril (external ostium, naris), formed by the alar rim, the lateral border of the columella, and the floor of the vestibule.

Area 2: the nasal valve area (internal ostium, isthmus).

Area 3: the area underneath the bony and cartilaginous vault (also called the “attic”).

Area 4: the anterior half of the nasal cavity, including the heads of the turbinates and the infundibulum or osteomeatal complex.

Area 5: the posterior half of the nasal cavity, including the tails of the turbinates.

This five-area division was taken over by several authors like ourselves. In several German textbooks (Ey 1984, Masing 1977, Rettinger 1988) however, the denomination “area 3” was given a to another region (the premaxillary area) than in the Cottle system. This has diminished the value of the five-area division.

Five-Structure Division of Bachmann-Mlynski

Bachman (1982) and recently Mlynski et al. (2001) have divided the nose on the basis of its inspiratory function into five different structural elements: the vestibulum, the isthmus, the anterior cavity, the area of the turbinates, and the posterior cavity, choanae, and epipharynx.

Three-Structure Division (this book)

In this book we suggest a subdivision into three anatomical-physiological parts (Huizing 2003) (see also p. 46, Fig. 1.85):

the anterior segment or upstream area consisting of the nostril, vestibule, and valve area;

the middle segment or functional area proper consisting of the mucosa-lined nasal cavity with the turbinates, septum, and sinus ostia; and

the posterior segment or downstream area with the tails of the turbinates, anterior wall of the sphenoid, and choanae.

Fig. 1.34 Structures bounding the nostril.

Nostril (Naris, External Ostium)

The nostril is formed by the alar rim, the lateral border of the columella with the protruding end of the medial crura, and the nostril sill (Fig. 1.34). In the normal adult Caucasian nose, the nostril has an ovaloid form with a slightly oblique axis. In newborns and young children, it is almost round. It gradually changes to the adult ovaloid aperture during school age and puberty.

In the Black and Asian nose, the nares are also more round. In some types of Black nose the external ostium may have an almost horizontal axis. These racial and age variations are also expressed in the magnitude of the lobular index.

Vestibule

The vestibule is the skin-covered inner part of the lobule (Fig. 1.35). The following structures are of clinical and surgical significance (see also p. 36 and Figs. 1.72a, b and 1.76 a):

medially:

- the columella with the medial crus of the lobular cartilage;

- the membranous septum;

- the skin covering the caudal end of the cartilaginous septum.

internal ostium or laterally:

- the inside of the ala with the lateral crus and its more or less protruding end;

- the cul de sac or infundibulum, a shallow pouch bounded laterally by the cranial part of the lateral crus and medially by the caudal part of the triangular cartilage.

Fig. 1.35 Vestibule and valve area with its various structures.

Fig. 1.36 Nasal valve area. 1. Valve angle. 2. Cartilaginous septum. 3. Ventrolateral process of the cartilaginous septum and premaxillary wing. 4. Caudal margin of the triangular cartilage (limen nasi). 5. Fibrofatty tissue area. 6. Head of the inferior turbinate. 7. Nasal floor.

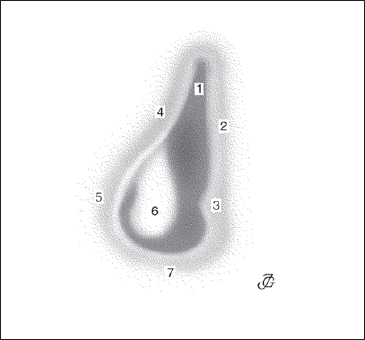

Valve Area (Internal Ostium)

The valve area is a more or less triangular or teardrop-shaped area which gives access to the internal nasal cavity (Fig. 1.36). Its original name was: “ostium internum” (Zuckerkandl 1882) or “isthmus nasi.” Later it was considered a “valvular device controlling the inflow of air” (Mink 1902, 1903). Nowadays, we call it the valve area (Kern 1978). As the narrowest region of the internal nose, it causes the most resistance to breathing. The valve area is bounded:

medially by:

- the cartilaginous septum;

- the premaxillary wing.

laterally by:

- the lower margin of the triangular cartilage or limen nasi;

- the fibrofatty tissue area;

- the head of the inferior turbinate.

caudally by:

- the skin-covered floor of the piriform aperture.

The medial wall of the valve area is rigid, where as the lateral wall is mobile. At inspiration, it moves inward due to the negative pressure caused by the inspiratory airflow. At expiration it moves outward. The inward movement is counteracted by the mass and stiffness of the triangular and lobular cartilages, soft-tissue areas, and the connecting fibers and musculature (see p. 36, 37 and Figs. 1.72 a–c).

Terminology of the valve area

Valve area: narrowest area (area 2) of the internal nose. It is bounded medially by the cartilaginous septum and the premaxillary wing; laterally by the lower margin of the triangular cartilage, the fibrofatty tissue area, and the head of the inferior turbinate; and caudally by the skin-covered floor of the piriform aperture.

Valve: the moving part of the lateral wall of the valve area, i.e., the caudal margin of the triangular cartilage.

Valve angle: the angle between the caudal margin of the triangular cartilage and the septum.

Ostium internum: old name for the valve area. This name was introduced by anatomists (Zuckerkandl 1883) in the 19th century in contrast to “ostium externum” (naris, nostril).

Fig. 1.38 Perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone and the vomer.

Isthmus: narrowest area of the nasal cavity (= valve area).

Limen nasi: lower margin of the triangular cartilage (= valve).

Septum

The nasal septum consists of: 1) the cartilaginous septum; 2) the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone; 3) the vomer; and 4) the septal framework.

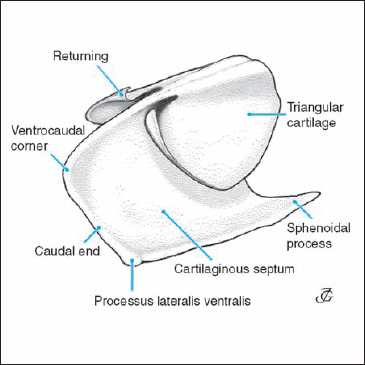

Cartilaginous Septum

The cartilaginous septum is part of the septolateral cartilage. The following structures are of special clinical and surgical interest (Fig. 1.37):

- the free caudal end,

- the processus lateralis ventralis: a broadening of its caudal margin in the area where the cartilage is connected to the premaxilla,

- the ventrocaudal corner (anterior–inferior corner), and

- the sphenoidal process (= posterior process): a posterior extension of the cartilaginous septum between the perpendicular plate and the vomer. See also page 28, 29 and Figures 1.63a, b and 1.64a, b.

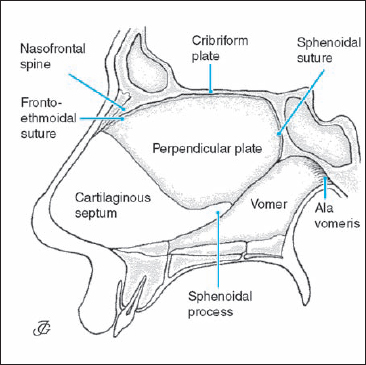

Perpendicular Plate of the Ethmoid Bone (Lamina Perpendicularis)

The perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone is a more or less quadrangular, thin, bony plate. Its upper border is ventrally attached to the posterior surface of the nasal spine of the frontal bone (fronto-ethmoidal suture). More posteriorly it is united to the inferior surface of the cribriform plate (Fig. 1.38). The posterior margin unites with the sphenoidal crest (sphenoidal suture). The caudal margin is attached to the anterior border of the vomer. The ventral margin unites with the cartilaginous septum. This part often has two cortical layers with spongiotic bone marrow in between. On rare occasions, a bulla may be present (see also page 30 and Figs. 1.65a, b).

Vomer

The vomer is an unpaired, oblong, quadrangular bone resembling a plowshare. Its cranial margin is broad and split into two lateral leaves (alae vomeris). These are attached to the sphenoid bone. Its posterior margin forms the medial wall of the choanae. Its inferior margin, which is sharp and serrated, is connected to the maxillary and palatine crests. The anterior (to some extent also cranial) margin is somewhat thickened. It has a groove in which the inferior margin of the perpendicular plate and the cartilaginous septum are fixed.

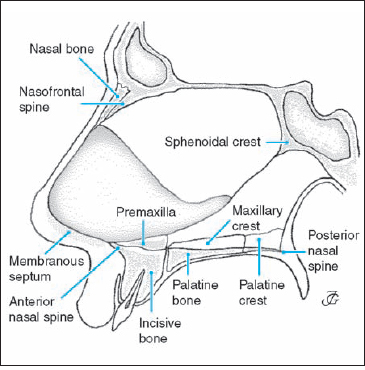

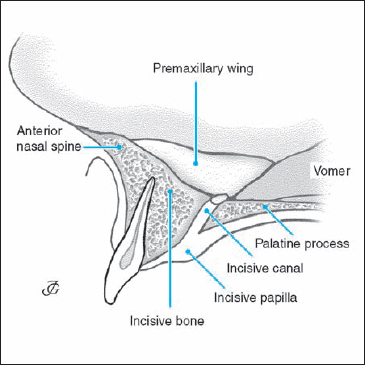

Septal Framework

The septal framework holding the septum consists of eight different anatomical structures (Fig. 1.39):

Caudally:

- anterior nasal spine (spina nasalis anterior)

- premaxilla with the premaxillary table and the premaxillary wings

- maxillary crest (crista nasalis maxillae)

- palatinal crest (lamina horizontalis ossis palatini)

- membranous septum (septum membranaceum).

Ventrally:

Bony ridge at the dorsal side of the nasal bones.

Cranially:

Bony ridge at the junction of the cribriform plates.

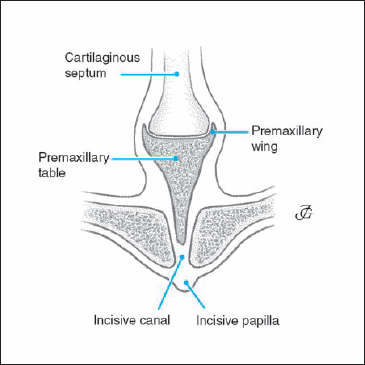

Fig. 1.40 Chondropremaxillary complex (a) and the chondromaxillary junction (b).

Fig. 1.41 Premaxilla and premaxillary wings

Dorsally:

Sphenoidal crest (crista sphenoidalis), a bony ridge at the junction of the two sphenoidal sinuses.

Junctions between the Septum and its Framework

Precise knowledge of the connections between the various parts of the septum is of the utmost importance in septal surgery. In particular, the junctions between the cartilaginous septum and the anterior nasal spine and the premaxilla are of great importance. Detailed information is presented in Figures 1.39–1.42 and on page 28 ff (Figs. 1.63 a–c; 1.64 a–d; 1.65a, b).

Fig. 1.42 Premaxilla and incisive canal.

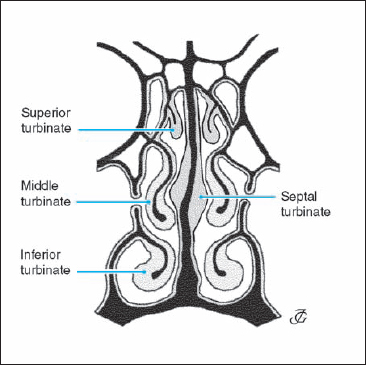

Fig. 1.43 Inferior, middle, superior, and septal turbinate.

Fig. 1.44 Lateral nasal wall with: 1. Inferior turbinate. 2. Middle turbinate. 3. Superior turbinate. 4. Agger nasi. 5. Supreme turbinate

Incisive Bone

Although the terminology of Figures 1.39–1.42 is common in clinical practice, it is different from that found in major anatomical textbooks. The existence of an incisive bone (os incisivum) is indisputable since it has centers of ossification that are distinct from those of the main maxillary mass. The fusion of the incisive bone with the maxillary bone takes place well before birth and does not leave a trace on its facial aspect. On the palatine side, however, a suture (the incisive suture), running from the incisive fossa in anterolateral direction, is visible at birth. This suture may persist for several decades.

The incisive bone might therefore be described as the part of the maxilla anterior to the incisive fossa. It maybe considered the same bone as the premaxilla, which is a separate bone in most vertebrates. In anatomical textbooks the structure referred to as premaxilla in Figures 1.39–1.42 is described as the most anterior part of the nasal crest of the maxilla and is also known as the incisor crest. It is the highest part of the nasal crest. It projects ventrally, together with its contralateral fellow, as the anterior nasal spine and flattens superiorly to form the premaxillary table and wings (Figs. 1.40 a, 1.41).

Turbinates and Turbinate-Like Structures

In each nasal cavity, six to eight turbinates and turbinate-like structures can be distinguished (Figs. 1.43, 1.44).

On the lateral nasal wall we find:

- the inferior turbinate (concha nasi inferior)

- the middle turbinate (concha nasi media)

- the superior turbinate (concha nasi superior)

- the agger nasi, and in some cases

- the supreme turbinate (concha nasi suprema).

On the medial nasal wall we find:

- the septal turbinate (also known as tuberculum septi, intumescentia septi, and Kiesselbach’s ridge), and in some cases several

- posterior septal ridges or folds.

(See also p. 34 and Fig. 1.70a).

Hippocrates called the turbinates “sleeves.” Casserius (1610) gave them their present name (He wrote: “the use of the turbinate bones is to break the force of the entering air and warm it and cleanse it”).

Turbinates

The turbinates should be considered separate structures with a similar, but not completely identical function. Their bony skeleton may be lamellar, spongiotic, or bullous.

- The lamellar type is the most common, especially in the inferior turbinate. Its architecture may differ in the way the bony lamella protrudes into the nasal cavity.

- The spongiotic type is frequently seen in the inferior and middle turbinate and also in the bony septum underlying the septal turbinate.

- The bullous type is present in the middle turbinate in about 25% of the population. It is a very rare finding in the inferior turbinate.

The cavernous parenchymal tissue is by far the most developed in the inferior turbinate. It is also relatively thick at the medial and posterior part of the middle turbinate. It is negligible in the superior turbinate. These variations illustrate the functional differences of the turbinates and their parts

The mucosal lining of the various turbinates also shows certain differences in the number of cilia-bearing cells and glands

Because of their extensive submucosal capillary bed and the abundance of serous and mucous glands, the mucosal surface greatly contributes to the humidification, warming, and cleansing of the inspired air. This is made possible by the thick mass of cavernous tissue in between the submucosa and the bony skeleton. The conchal parenchyma is made up of arterioles, venules, and an extensive capillary bed embedded in loose connective tissue. Congestion and decongestion of the cavernous plexus is regulated by a complex autonomic nerve system that is influenced by a number of endogenous and exogenous factors (see p. 26).

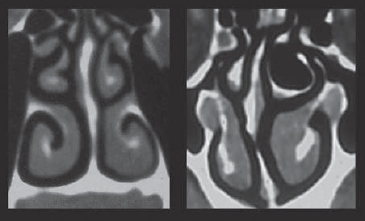

The inferior turbinate is the largest of the four lateral turbinates. It is derived from the maxillary bone. As in mammals, it may therefore be called the “maxilloturbinale.” For clinical and surgical purposes we distinguish a turbinate head, body, and tail. These three parts differ in terms of function and pathology

The bony skeleton consists of a solid or spongiotic lamella extending from the lateral bony nasal wall into the nasal cavity (see p. 34 and Fig. 1.70b). The angle between the turbinate bone and the bony lateral nasal wall may vary considerably, from about 20° to 90° (Fig. 1.45). These differences may contribute to inferior turbinate pathology. They should therefore be taken into account in planning turbinate surgery. The mucosa of the inferior turbinate is thicker than in the upper part of the nasal cavity. The cavernous parenchyma of the inferior turbinate is much more massive than that of other turbinates. In the congestive state it may increase its volume three to four times compared with its decongested state, thereby almost completely blocking the inferior nasal passage (see also p. 34, 35 and Fig. 1.70a, d, e).

Fig. 1.45 CT scans of the inferior turbinate demonstrating the large variation of the angle between the turbinate bone and the bony lateral nasal wall.

Fig. 1.46 Middle turbinate: plate or lamellar type (a), spongiotic type (b), and bullous type (c).

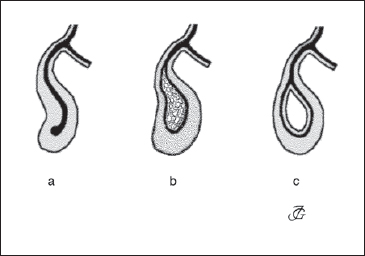

The middle turbinate is part of the ethmoid bone. This explains why its skeleton may be more or less pneumatized. It is comparable to the ethmoidoturbinale I in mammals. The bony skeleton (Fig. 1.46) may be of the lamellar, spongiotic (concha spongiosa), or bullous type (concha bullosa).

- The lamellar type is characterized by a curved bony plate extending from the lamina papyracea. This plate divides the ethmoid bone into an anterior and posterior part. Its free end may be more or less straight, curved inward, or curved outward.

- The spongiotic type is less common. The bony skeleton is made up of two cortical layers and spongiotic bone with bone marrow in between. As a result, the turbinate may be relatively thick which may play a role in pathology

- The bullous type is a common variation found in about 25% of normal individuals. The skeleton consists of an ovaloid ethmoidal cell with thin walls. Its inside is lined with mucosa, and it usually drains through an ostium into the infundibulum. A concha bullosa may have a considerable size and may be multichambered. As a result it may be in permanent contact with the septum and/or obstruct the infundibulum. Although a normal variation, a concha bullosa may thus play a role in nasal and sinus pathology.

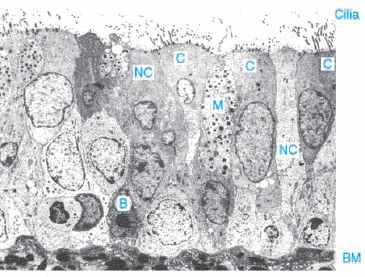

Fig. 1.48 Nasal mucosa (TEM) (from Schuil, Thesis Utrecht 1994)

C = ciliated columnar cell

NC = nonciliated columnar cell

M = mucus-producing goblet cell

B = basal cell

BM = basement membrane

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree