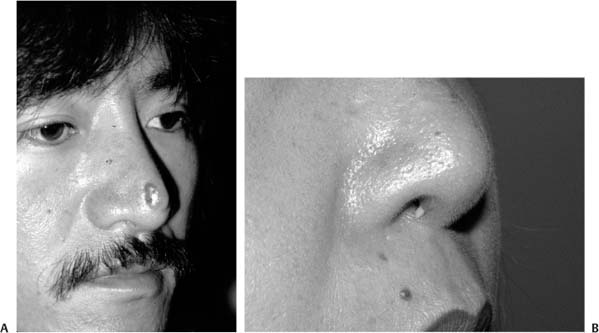

3 Although some Asian noses, most commonly in patients originating from the central and northern latitudes of Asia, benefit from the classic techniques employed in reduction rhinoplasty, the majority of such noses require an augmentation procedure to achieve maximum aesthetic benefit. The anatomy of these noses is characterized by a broad, flat dorsum with a shallow, depressed origin at the nasion (Fig. 3-1A). The lobule is generally wide and often exhibits columellar retraction that may be accompanied by alar flaring. Although there are substantial individual variations, lobular skin tends to be thick and well endowed with abundant subcutaneous fibrofatty tissue. Tip projection is frequently deficient, and the lower lateral cartilages are usually thin and attenuated. Augmentation rhinoplasty is extremely popular in East Asia and is requested with increasing frequency in North America and Europe, as well as in other areas with large Asian populations. Although it might be assumed that this is indicative of a desire for “westernization,” it should be noted that in Asian cultures, a high, narrow nasal bridge is an aesthetically desirable feature. Few procedures in facial plastic surgery elicit the controversy that surrounds augmentation rhinoplasty in the Asian nose. Regardless of whether a nose requires reduction or augmentation, the aesthetic goals of rhinoplasty are the same: creation of a strong, smooth dorsum exhibiting a prominent origin at the nasion but not competing with the tip as the leading point of the nasal profile (Fig. 3-1B). Ideally, the lobule should be delicate and well defined, with definite columellar “show” and an oblique anteroposterior orientation of the nares. The nasolabial angle varies depending on the height of the individual patient. The characteristics of the ideal nasal lobule are the same regardless of ethnicity (Table 3-1). In spite of the fact that there is agreement on the goals of Asian rhinoplasty, few procedures in facial plastic surgery elicit the controversy that surrounds augmentation rhinoplasty in the Asian nose, largely relating to the polarization of opinion regarding the choice of material best suited to achieve these objectives. This polarization generally follows geographical lines; Asian surgeons generally prefer alloplasts, particularly custom-crafted silicone implants, whereas Western surgeons tend to be more comfortable with augmentation procedures employing autogenous materials. Some academic Asian surgeons have begun to use autogenous materials for tip rhinoplasty (frequently in combination with silicone prosthesis for dorsal augmentation), often employing the external rhinoplasty approach. Although rank-and-file surgeons in the West tend to recognize the benefits of alloplasts, a strong academic bias against the use of alloplastic materials in any segment of the nose persists in Western countries. In the recent past, some influential surgeons have condemned silicone implants with the fervor of a Pentecostal preacher, admonishing that their use in the nose constitutes a cardinal sin of rhinoplasty, obviously ignoring the fact that long-term results using this material in the Asian nose have been excellent. As a result, few Western surgeons who advocate augmentation of the Asian nose with alloplasts have reported their results, and those who dare to submit such reports often assume a deferential, quasi-apologetic posture, fearful of being summarily crucified on the altar of fundamental dogma. Figure 3-1 (A) The typical Asian nose demonstrating a relatively flat dorsum and sufficient tip projection. (B) Following augmentation rhinoplasty, both dorsum and tip show increased projection. Note the improvement in columellar “show” and the “double break” at the junction of the tip defining point and columella. Thus, although augmentation with silicone implants remains the “bread and butter” of rhinoplasty in Asia, Western surgeons, historically at least, have forgone the tremendous advantages offered by this material. Recently enlightened surgeons suggest that, although alloplastic material may be satisfactory for augmentation of the dorsum, lobular modification is probably best performed using autogenous materials. Techniques of tip rhinoplasty that are highly successful in the Caucasian nose are usually unsatisfactory in Asians because the attenuated lower lateral cartilages lack sufficient strength to accentuate tip projection and support, and the overlying skin and subcutaneous tissue are too thick to reflect sculpturing of the delicate cartilage. Thus, if tip projection is to be enhanced, the surgeon generally must reinforce or buttress lobular cartilage with cartilage grafts. Although such techniques often prove satisfactory for lobular enhancement alone, when accompanied by a dorsal alloplast, discontinuity between the dorsum and lobule is all too common, frequently being unapparent until final resolution of postoperative edema or later in the postoperative period. In contrast, continuity between the dorsum and lobule is a major advantage of L-shaped silicone prostheses.

Asian Rhinoplasty

♦ General and Historical Considerations

|

My 27-year surgical experience in augmentation of the Asian nose has convinced me that the consistently superior aesthetics that can be achieved easily using silicone implants are rarely consistently matched by augmentation with other materials (Fig. 1A,B). This experience, as well as my observation of results produced by other techniques, leads me to the conclusion that for augmentation of the Asian nose, the use of an L-shaped silicone implant is a procedure of choice. A primary goal of this chapter is to provide convincing evidence that this procedure is deserving of serious consideration and respect and is not inherently dangerous, when properly planned and executed, as Western dogma has purported.

Asian craftsmanship, renowned throughout the world, is characterized by pragmatic concern for function along with a keen eye for beauty and symmetry coupled with meticulous attention to detail. Augmentation rhinoplasty using silicone implants has been developed and refined by conscientious, experienced, and well-trained Asian surgeons. Irrational criticism of this material as inherently dangerous or unreliable is disrespectful to the accomplishments and experience of our Asian colleagues. Consider that (1) augmentation with silicone implants dwarfs the use of other materials in Asia and (2) the majority of complications following any cosmetic nasal operation, including augmentation with alloplastic prostheses, are related to technical or judgmental error.

The challenge in augmentation rhinoplasty employing silicone implants is the same as for all surgery: formulation of a surgical approach that minimizes potential problems. Such an approach to augmentation rhinoplasty rests upon a foundation consisting of three key pillars: (1) the surgical technique per se, (2) design and fabrication of the implant, and (3) postoperative follow-up enlisting the patient as a partner.

In planning a recent presentation for an Asian audience, it occurred to me that a fourth pillar of the foundation for success relates to the surgeon’s conception of the operative goals. In the West, rhinoplasty is taught as a progressive series of steps, by far the most important of which is modification of the nasal lobule. Young surgeons are taught to first fix the position or projection of the tip and then alter the dorsum to complement tip position. Inadequate or excessive surgical manipulation of the lobule constitutes a virtual “kiss of death” for the entire rhinoplasty procedure. Surgery of the dorsum, in contrast, is relegated to the back burner, being virtually an afterthought, consisting of a mundane series of maneuvers that are relatively easy and forgiving of all but the most glaring of errors.

When, however, a Western surgeon conceives of augmentation of the Asian nose, his or her primary consideration is modification of the dorsum, lobular aesthetics playing a secondary role. Early versions of dorsal prostheses produced in the West provide graphic evidence of this observation. Attempts to refine and sculpture the lobule with conventional Western tip rhinoplasty techniques rarely bear fruit as a consequence of the anatomy of the Asian lower lateral cartilages, a fact that contributes to the relative neglect of this area.

I attribute whatever success I have achieved in performing and teaching augmentation rhinoplasty in the Asian nose largely to my persistence in retaining the Western concept of modification and enhancement of the lobule as a primary goal of this procedure, just as I do when performing reduction rhinoplasty.

A collateral benefit of this mindset is the additional margin of safety provided by virtue of the fact that the physical limitations of lobular augmentation are easily visualized intraoperatively if this area is the surgeon’s primary focus. If the primary goal is dorsal augmentation, there is a temptation to “fit” the lobule to a more aggressively modified dorsum, a prescription for disaster, as lobular augmentation is the weak link of this procedure.

♦ A Personal Odyssey

A brief historical narrative describing the process by which my current approach to this operation developed may prove to be instructive.

During my residency training from 1973 to 1976, I operated on only an occasional Asian nose, for which augmentation involved autogenous cartilage (nasal septum and conchal cartilage). At times, complications of alloplastic augmentation were presented in our clinics, and we listened and believed admonitions against the use of alloplasts in the nose.

Between 1976 and 1979, I served at the Tripler Army Medical Center in Honolulu, Hawaii, and performed Asian augmentation rhinoplasties initially using autogenous cartilage; during the latter stages of this assignment, I began to use Mersilene mesh (polyethylene terephthalate) for augmentation of the nasal dorsum. Lobular sculpturing during this time was attempted using the basic techniques of tip surgery, but the results tended to be unimpressive. During this period, I developed a relatively large practice in Asian blepharoplasty, but this did not translate into an increased number of patients requesting nasal augmentation.

In 1979 I entered private practice and again utilized autogenous cartilage and Mersilene along with standard tip rhinoplasty techniques. Although my practice in Asian blepharoplasty blossomed, there was not, to my surprise, a concomitant increase in the number of patients requesting augmentation rhinoplasty. Prominent surgeons serving as panelists at national meetings during this time continued to equate the use of alloplastic material for augmentation of the nose with malpractice.

By 1981 it finally occurred to me that the reason my practice of augmentation rhinoplasty was stagnating was that my Asian patients were underwhelmed by the results that I achieved with the techniques that I used. Even though I was reasonably satisfied with the results, my patients, although rarely complaining overtly, did not share my enthusiasm. During my residency training and first 2 years of private practice, I had encountered numerous patients who had undergone previous augmentation with alloplastic material; most were very pleased with the results. I realized that if I were to be successful, that I must change my thinking and learn the safe and proper use of silicone prostheses for augmentation rhinoplasty. My results did improve, and my practice of Asian augmentation rhinoplasty increased dramatically.

Figure 3-2 (A) Extrusion of a silicone prosthesis through the lobule. (B) Exposure of an implant via the columella.

Looking back over this experience, I realize that the results achieved using autogenous cartilage and mesh were suboptimal because of the failure of standard techniques of lobular surgery to improve tip aesthetics. As I gained more experience with silicone prostheses, I realized that the ability of an L-shaped silicone prosthesis to sculpture the lobule as well as augment the dorsum in continuity with the lobule was the reason for improved aesthetic results, and that focusing on augmentation of the dorsum in the Asian nose rather than on improved lobular aesthetics led to inferior results. Use of an L-shaped prosthesis allowed for the shifting of my primary focus in augmentation rhinoplasty to enhancement of the lobule, just as it had for Caucasian rhinoplasty, relegating dorsal augmentation as a procedure that must complement, not overwhelm, lobular enhancement.

♦ Why Are Silicone Implants Held in Disrepute?

Before building the case for silicone implants as a procedure of choice in augmentation of the Asian nose, it is helpful to explore the reasons why silicone implants are held in such disrepute in the West. It is difficult to dispel the negative impressions engendered by photographs showing extrusion, most commonly in the lobular region, of alloplastic implants. In contemporary augmentation rhinoplasty, this situation is extremely rare. Most cases of implant exposure occur in the columella and are preceded by warning signs that allow early prophylactic intervention (Fig. 3-2A,B).

The poor results of augmentation using a dorsal prosthesis fabricated by Western companies (Fig. 3-3) have undoubtedly contributed to the poor impression of silicone implants. In addition, early Asian prostheses tended to be poorly designed, generally being excessive in size and constructed of firm elastomer. Another factor contributing to the notoriety of silicone implants has been the occasionally horrifying results of liquid silicone and paraffin injections, which, in the past, were common in Asia. It must be stressed that the reasons for historical disrepute are no longer valid because of advances in materials, surgical technique, and understanding of the dynamics of augmentation rhinoplasty.

Figure 3-3 Dorsal silicone prosthesis manufactured in the West, circa 1978.

♦ Choosing Prosthesis Material

All surgeons will agree that multiple factors are important in the choice of a material for augmentation rhinoplasty. Among these factors are the reliability, reproducibility, and precision of results, as well as the morbidity and complication rate, one measure of which is the incidence of revision surgery. Cost effectiveness is another consideration, as is patient satisfaction following augmentation. An L-shaped silicone prosthesis properly fabricated and placed with meticulous attention to technical detail rates an A+ in all of these categories.

♦ Formulating an Approach to Augmentation Rhinoplasty

Formulation of an approach to augmentation rhinoplasty employing silicone prostheses rests on four key pillars: (1) implant design, (2) surgical technique, (3) postoperative follow-up enlisting the patient as a postoperative partner, and (4) focusing on creation of superior lobular aesthetics rather than dorsal augmentation as the primary goal of the procedure. My goal is to present a detailed blueprint for planning and executing operations using an L-shaped silicone prosthesis.

|

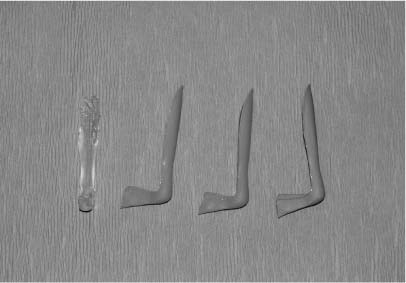

Figure 3-4 L-shaped silicone prostheses.

Implant Design

| See DVD Disk Two, Nasal Implant Selection |  |

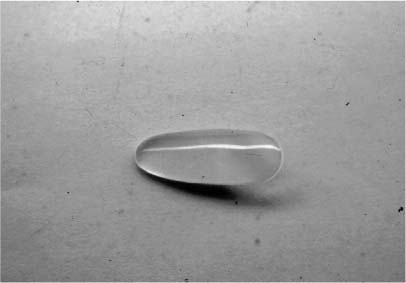

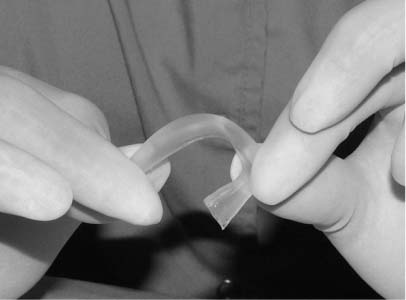

The silicone implant that I designed (Table 3-2) and currently use consists of three segments, each having distinct characteristics and functions: a dorsal component, a lobular component, and a columellar strut (Fig. 3-4). All three components are made of soft silicone elastomer, of particular importance in that softness and flexibility (Fig. 3-5) translate into diminished pressure at the tissue-prosthesis interface, resulting in less stress on the overlying skin. Historically, the first generation of silicone nasal implants designed in Asia were fabricated from hard elastomer and tended to be of excessive size, factors that contributed to complications, most notably implant exposure.

The soft, flexible dorsal component has a groove on its posterior surface that allows apposition to the dorsum. All edges are tapered to facilitate inconspicuous blending, thus minimizing prosthesis palpability or visibility.

Figure 3-5 The flexibility of the soft L-shaped prosthesis is demonstrated.

The most misunderstood component of the L-shaped nasal implant is the columellar strut (Table 3-3). Perhaps because surgeons who use struts of autogenous material teach that postoperative lobular position is a function of the thrusting action of these struts, it is assumed that the alloplastic strut functions in a similar manner. Utilization of the strut as a tent pole to increase tip projection, however, is a prescription for disaster.

In actuality, the columellar strut has two functions. First, it stabilizes the proximal (lobular) segment of the implant in the midline, thus providing resistance against displacement and malposition. Second, the strut allows sculpturing of the columella by displacing the characteristically retracted columella of the Asian nose inferiorly, thus increasing its show. An understanding of these two functions of the columellar strut allows the surgeon to resist any temptation to extend the strut the full length of the columella, thereby producing an undesirable “tent-pole” effect, because to perform its functions, the columella strut need extend only 50 to 75% of the columellar length.

In earlier years, I believed that a columellar strut fabricated from firm elastomer was best, as it could be relatively short and thin because of the resistance of the firm elastomer to deformation. This belief, however, proved to be erroneous because contraction of the fibrous capsule that naturally forms around the prosthesis often exerts a rotational force that occasionally results in displacement of the strut laterally. Pressure from such displacement may result in perforation in the vestibular aspect of the columella, that is, the site of the incision, by far the most common site of implant exposure. The rotational forces are less likely to be effectively transmitted to a columellar strut fabricated from soft elastomer because of the flexibility at the lobular-columellar junction of the implant. This flexibility, however, will result in superior displacement of the strut (by columellar tension) unless the strut has sufficient breadth to allow it to be wedged between the caudal septum and columellar skin/medial crura. Intraoperatively, the flared strut is carefully trimmed so that it fits gently between the medial crura and caudal septum at the most anterior point that allows aesthetically sufficient inferior displacement of the columella (producing columellar show). The inferior inclination (angulation) of the columellar strut with respect to the dorsal component assists in achieving this goal. Other commercially available nasal implants are constructed so that the columellar strut projects at a 90-de-gree angle from the dorsal component, a situation that renders the strut virtually useless in producing columellar show and reinforces the improper notion that the strut is of value for increasing tip projection.

|

It cannot be overemphasized that after final trimming, the columellar strut never extends posteriorly for a distance of greater than 75% of the length of the columella. Allowing the strut to contact the nasal spine and/or maxilla results in a “tent-pole” effect—an invitation to disaster in the form of implant extrusion secondary to pressure necrosis of the lobular skin. It cannot be stressed enough that the function of the strut is not to project the lobule; lobular projection is achieved by the cantilever effect of the rounded, slightly elevated lobular and contiguous dorsal segment in a fashion analogous to the cantilever action of bone grafts utilized for total nasal reconstruction.

Because of complaints that clear silicone implants may be visible through the nasal skin under bright indoor lighting, an implant of a neutral color (e.g., beige or flesh toned) should be considered, especially if the patient is fair complexioned.

Surgical Technique

| See DVD Disk Two, Alloplastic Augmentation Rhinoplasty |  |

Preoperative Considerations

Of major importance in preoperative evaluation is detection of factors that may be relative or absolute contraindications to the use of alloplastic material. Such factors include thin nasal skin, the presence of a substantial dorsal convexity, and, importantly, an acute nasolabial angle (i.e., a “plunging” tip), a condition the correction of which is difficult to accomplish with an L-shaped implant. Another important “red flag” is diminished tissue elasticity, perhaps the most frequent cause of which is previous nasal surgery. All surgeons, particularly those who are inexperienced in the use of alloplasts, must realize that use of a silicone implant in such situations involves “pushing the envelope”—a judgmental factor that predisposes to unsatisfactory results and complications.

Interestingly, nasal obstruction resulting from septal deviation is extremely uncommon in the Asian patient requesting augmentation rhinoplasty. Obstruction as a consequence of turbinate dysfunction or hypertrophy, however, approximates the incidence of this condition in Caucasian patients.

It is of utmost importance that candidates for augmentation rhinoplasty completely and carefully communicate the specifics of the nasal transformation that is desired. Many Asian patients assume that the surgeon knows best and will automatically construct a nose to their exact specifications. If communication between patient and surgeon is unclear or imprecise, disappointment may ensue regarding matters such as dorsal height and contour, lobular configuration, and tip projection. It should be stressed to the patient that the surgeon cannot promise to construct a nose to exact specifications.

In previous times, most surgeons assumed that Asian patients requesting augmentation rhinoplasty desired as much enlargement as possible to achieve a Western look. In contemporary practice, however, most Asian patients do not desire westernization, but more subtle augmentation. A common request in 21st-century Asian rhinoplasty is “Please don’t make my nose too high; I want it to match my Asian face!” This is a fortunate attitude in that the desire for conservative augmentation is a major ally in the quest for safety when using alloplastic materials. As emphasized previously, a focus on lobular aesthetics as the primary goal of the procedure reinforces intraoperative conservatism.

Surgical Approach

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree