CHAPTER 34 Arthrodesis of the Tarsometatarsal Joint

OVERVIEW

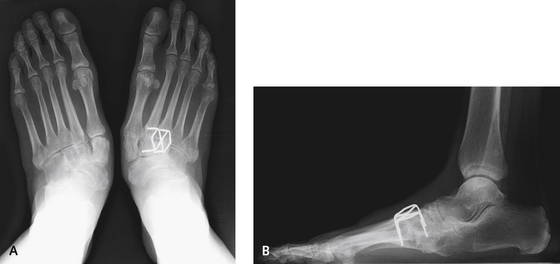

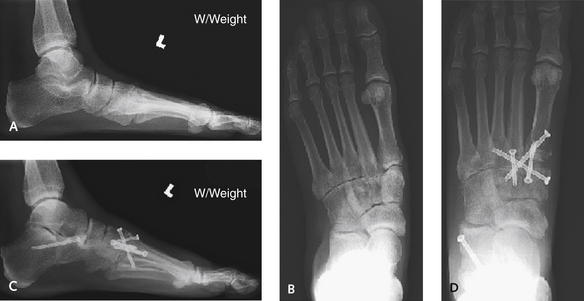

Arthrodesis of the tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint is performed for treatment of arthritis of variable extent with or without deformity, in the setting of idiopathic osteoarthritis or posttraumatic or inflammatory arthritis, and for correction of neuropathic deformity. The arthrodesis should be limited to symptomatic joints, which are not always easy to identify. A combination of the location of the patient,s symptoms, the appearance on plain radiographs and findings on clinical examination will determine the joints to be fused. The radiographic appearance of the lateral column is not always helpful with the decision-making process because the lateral column often is asymptomatic despite the radiographic presence of arthritic changes (Figure 34-1). All involved segments of the midfoot should be included in the arthrodesis, which often will extend to the naviculocuneiform and intercuneiform joints (Figure 34-2). Such extensive involvement is particularly common after trauma, when arthritis and deformity may include the intercuneiform and naviculocuneiform joints—hence use of the term tarsometatarsal joint complex to designate the relevant anatomy.

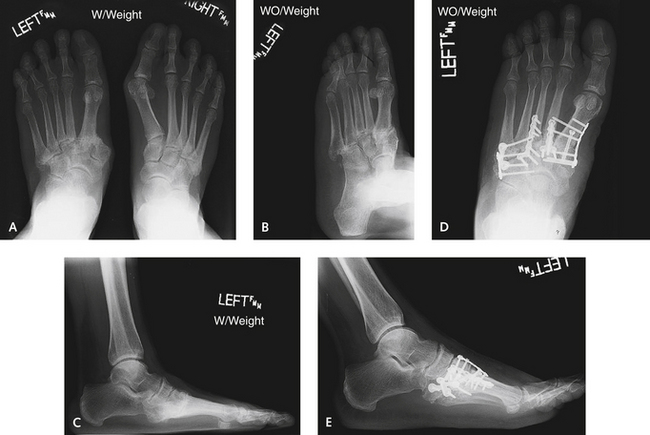

In some instances, as with a flatfoot deformity associated with hindfoot valgus, the hindfoot deformity is primary and the arthritis of the TMT joint is secondary; nevertheless, the hindfoot deformity must be adequately corrected in addition to the obvious painful focus, which as perceived by the patient may be only the TMT joint (Figure 34-3). In other situations, the midfoot deformity clearly is primary and the deformity of the hindfoot occurs secondarily, as in the case shown in Figure 34-4. In this example, severe dislocation involved the entire TMT joint complex including the lateral column. Although I rarely include the lateral column in the arthrodesis, here the entire midfoot required arthrodesis as a consequence of crushing of the cuboid and lateral foot pain. In order to correct this rather severe deformity, each joint was first debrided and the lateral contracture was released by lengthening the peroneus brevis tendon. Such severe deformities also may necessitate temporary lengthening of the lateral column with an external fixator, followed by reduction of the medial and middle columns (Figure 34-5). In the case illustrated in Figure 13-4, after complete “loosening” of each joint was achieved with debridement, the peroneus brevis was lengthened and the external fixator applied. The fixation was then initiated from medial to lateral, commencing with placement of temporary pins and followed by application of a combination of plates, including F3 plates (DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc., Warsaw, Indiana) for the second and third TMT joints and Maxlock plates (Orthohelix, Akron, Ohio) for the first, fourth, and fifth TMT joints.

DEFORMITY CORRECTION PRINCIPLES

Incision and Exposure

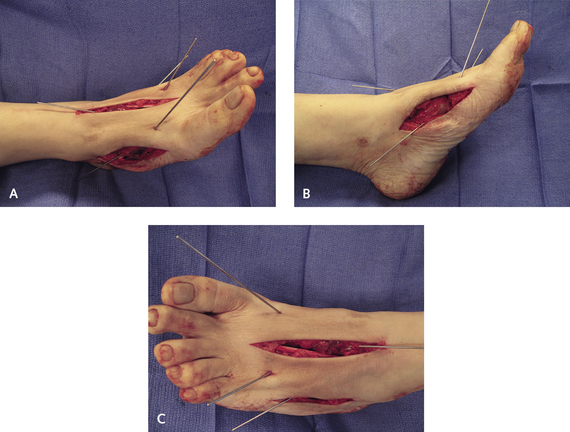

If the planned arthrodesis includes two adjacent joints, I try to use only one incision, if possible. For the middle column arthrodesis (of the second and third TMT joints), I use a single dorsal incision placed slightly more lateral than the second metatarsal, because the third metatarsal-cuneiform joint extends farther over toward the midline of the foot than is readily apparent. If the third metatarsal cuneiform joint is to be included in the arthrodesis, then the dorsal incision must be centered correctly over the midfoot, and not the second metatarsal. If the first and second TMT joints are to be fused, either one or two incisions can be used. With minimal deformity, I try to use one dorsal incision in the first TMT–second TMT interspace. If, however, both deformity and instability of the medial column are present, then I use a separate medial incision for access to permit plantar flexion of the medial column (Figure 34-6). I also use this incision when an extended navicular cuneiform metatarsal arthrodesis is performed that requires application of a plate from the medial aspect of the foot.

Once the dorsal incision has been deepened through subcutaneous tissue, the branches of the superficial peroneal nerve must be identified and then retracted. A neuroma on the dorsal surface of the foot is intolerably uncomfortable, and formation of these lesions can be avoided. The tendon of the extensor hallucis brevis is used as a guide to the location of the deep neurovascular bundle. Once the tendon is identified, the bundle is seen to lie directly underneath it, and both are retracted medially. The easiest way to retract is to undermine the bundle from the subperiosteal tissue over the second metatarsal and then elevate the flap, which includes the neurovascular bundle, using a large periosteal elevator.

The joint is prepared by removing the remaining articular cartilage with a flexible chisel. Perhaps the most important aspect of the joint preparation is aggressive perforation of the joint surface using a 1.5- or 2-mm drill bit, made at 1- to 2-mm intervals across the entire joint surface. I do not like to use a Kirschner wire (K-wire) for this purpose, because it seems to cause more bone burning. The only time I use a saw is for very severe deformity, as, for example, in a chronically abducted neuropathic midfoot, when I may want to correct a plantar medial rocker-bottom deformity. I prefer to keep the anatomy of the joints completely intact and remove as little bone as possible; therefore use of a saw is not ideal. The problem occurs with preparation of a hard sclerotic joint, which can be associated with posttraumatic or idiopathic osteoarthritis. The second metatarsal in particular can be quite avascular, and once this bone is debrided, the metatarsal shortens, resulting in a large gap in the joint. For this reason, aggressive perforation of the joint surface only is used to create a bone slurry, rather than debridement of the joint below the subchondral bone surface. The third metatarsal usually adheres well to the second metatarsal and will follow the second metatarsal into a corrected position. If the medial and middle columns are fused, then I try to debride the spaces between the first and second metatarsal bases and between the medial and middle cuneiforms and then place a bone graft in this location to further stabilize the arthrodesis. The metatarsals tend to dorsiflex with fixation, because debridement of the joint frequently is performed dorsally only. These are very deep joints, and the entire base of the metatarsal cuneiform joint must be completely debrided to prevent a dorsal malunion of the arthrodesis. Insertion of a smooth lamina spreader into the joint dorsally to visualize the plantar apical surface of the joint, before the arthrodesis is completed, is helpful. Frequently, small bits of bone remain on the plantar surface, which must be thoroughly cleared of such debris (Figure 34-7).