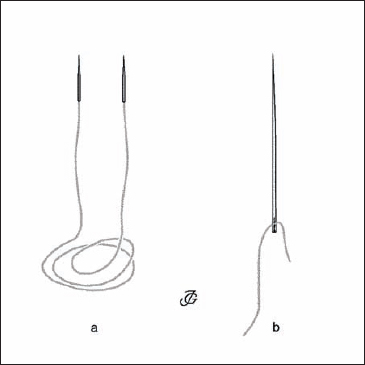

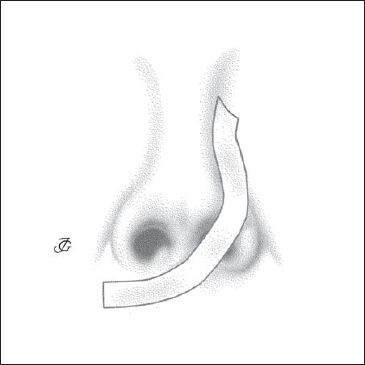

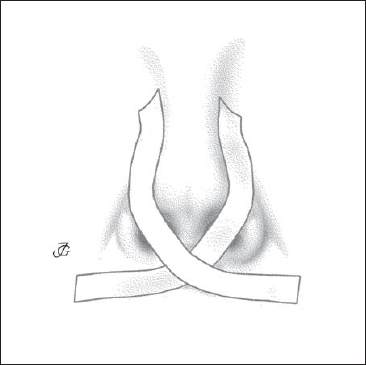

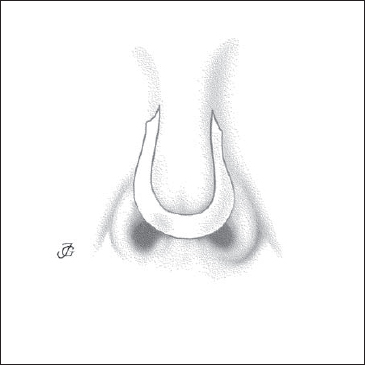

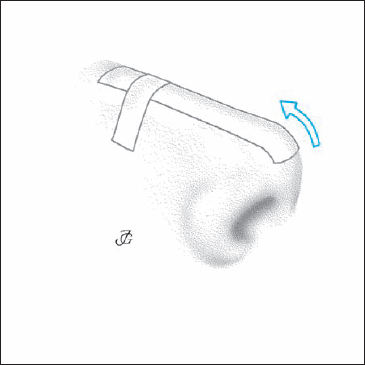

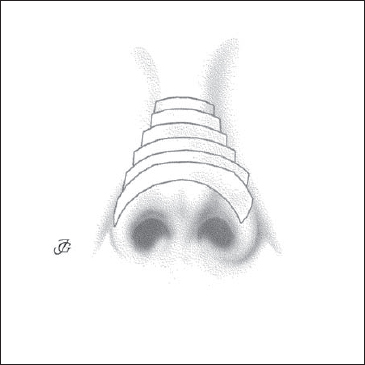

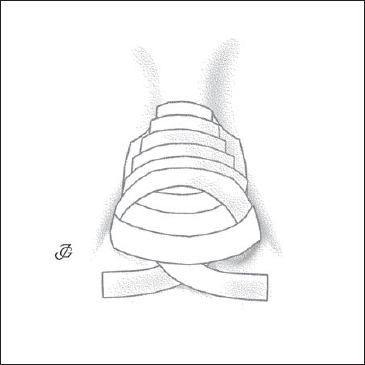

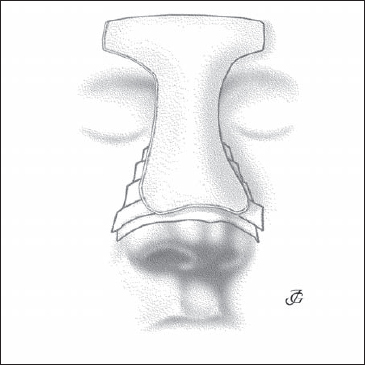

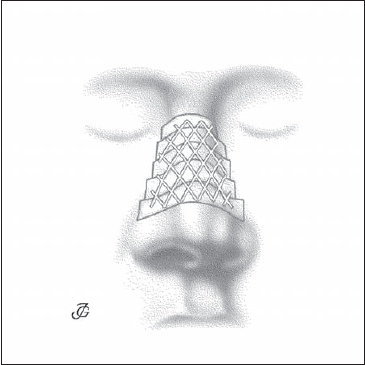

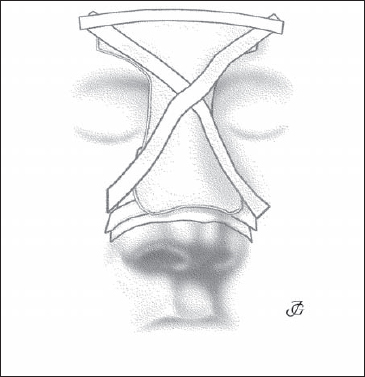

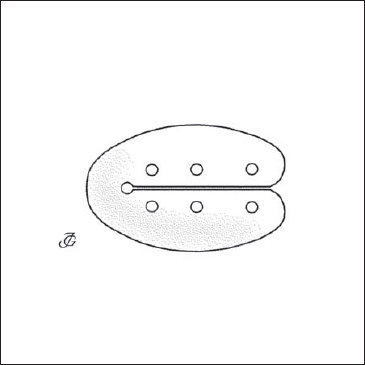

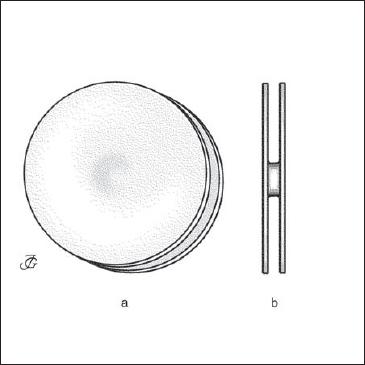

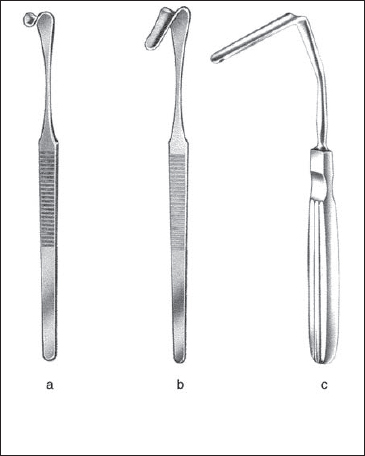

10 Appendix In functional reconstructive nasal surgery, incisions are almost always closed. The only exceptions are minor stab incisions. By closing the incisions, the tissues are adjusted and fixed in their new position; postoperative bleeding is prevented as well as scarring and stenosis. Endonasal mucosal and skin incisions are generally closed with resorbable materials such as Vicryl Rapide (4–0, or 5–0) or PDS (Polydioxanone). This applies to the common endonasal skin incisions used for approaches—such as the caudal septal incision (CSI), intercartilaginous (IC) incision, and vestibular incision—as well as all incisions of the septal and buccal mucosa. A great advantage of using resorbable sutures endonasally is that no sutures have to be removed from the inside of the nose during the first postoperative days. External skin incisions are closed with nonresorbable monofilament synthetic materials such as Ethilon or Prolene (5–0 or 6–0). These are also used to close special incisions in the nasal vestibule, such as infracartilaginous incisons. Fixation of plates or grafts of cartilage to rebuild the septum or other structures is usually done with slowly resorbable materials such as Vicryl or Dexon (2–0, 3–0, 4–0). Fig. 10.1a Vicryl 4–0 atraumatic with two short straight needles for transseptal, septocolumellar, and transcolumellar sutures. b Vicryl 3–0 with a straight long needle is used for septocolumellar sutures. Notes The numbers of the suture materials mentioned above are those used by the company Ethicon. In most countries, suture material made from animal tissue, such as catgut, is no longer used. It is forbidden because it is potentially hazardous for transmitting prion diseases. Incisions should be closed at all times. By closing the incisions, the tissues are adjusted and fixed in their new position, postoperative bleeding is prevented, and scarring and stenosis is avoided. Fig. 10.2b A repositioned pyramid is fixed in the midline by a bilateral sling. There is no consensus on the need for internal dressings. Many surgeons, like ourselves, prefer to apply them in almost all cases of septal, pyramid, and lobular surgery. Internal dressings serve three purposes: 1) to keep the septum in the midline and prevent septal hematoma; 2) to support the nasal bones, cartilaginous pyramid, and lobular cartilages in their new position; and 3) to limit risk of postoperative bleeding. We usually apply two loosely woven gauze strips either soaked in isotonic saline or with ointment. The first is applied endonasally to close the septal space and to support the nasal bones and cartilaginous pyramid. The second is applied in the vestibule after closure of the incisions (see Fig. 5.36). For a vestibular dressing, we consider Steristrip an ideal material. Others prefer to use preformed strips or “packs” of hydrophilic polyurethane, PVA (polyvinyl acetate) sponge or foam. Postoperative taping of the external nose is essential in all cases of pyramid and lobular surgery. Tapes are applied: 1) to adjust and keep the various soft tissues in their new position; 2) to diminish postoperative edema and the risk of hematomas and ecchymoses; and 3) to protect the surgical field. Depending on our surgical goals, we usually start by applying one or two specific tapes, such as: We will then apply pressure tapes on the whole bony and cartilaginous pyramid, dorsum, lobule, and nasal base to prevent edema and hematoma (Figs. 10.2e, f). Note Tapes are removed with cotton-wool applicators soaked in benzine. Fig. 10.2d A tip-lift tape fixes the tissues in their new position after upward rotation of the tip. Fig. 10.2e Pressure tapes on the dorsum fix a rib graft or other transplant material and prevent hematoma. Fig. 10.2f The external nose and the cranial half of the upper lip are completely taped for fixation and protection and to prevent edema. Internal dressing vs nasal packing We suggest using the term “internal nasal dressing” when gauzes are applied endonasally to adjust the repositioned nasal structures and keep them in their new position. The term “nasal packing” is only used when gauzes are more or less forcefully brought into the nasal cavity to stop nasal bleeding. External splints or stents are applied postoperatively for fixation, pressure, and protection. Several materials and types of stents are available. Because of its stiffness and perfect fit, a plaster-of-Paris stent may be applied in patients in whom the bony pyramid has been mobilized and repositioned. To provide maximal fixation and protection, the stent is usually fixed to the forehead (Fig. 10.3a). In cases where the surgery was limited the cartilaginous pyramid and/or lobule, thermoplastic material may be chosen. (Fig. 10.3b). Fig. 10.3b A stent of thermoplastic material (e.g. Hexcelite) offers less protection but can be remolded easily. Fig. 10.3c The stent is fixed with tapes to the forehead and cheeks. Plaster of Paris allows a very good fit but also has certain disadvantages. Making the stent is rather time consuming (it takes about 5 minutes to harden) and somewhat messy. A second drawback is that a stent of plaster cannot be remolded. Thus, if the postoperative swelling subsides after some days and the stent no longer fits, a new one has to be made. The use of thermoplastic material has the advantages of simplicity and cleanliness, while remolding is easy. The fit is not as good as with plaster of Paris, however. There are also soft aluminum splints on the market. Fig. 10.5 A prosthesis (“septal button”) is cut to measure for closing a septal perforation. Bilateral septal splintsmay be of great help in septal reconstruction (Fig. 10.4). Some surgeons use them more or less routinely after septal surgery. Others apply them only when the septum has to be more or less completely rebuilt. One advantage of using septal splints is not always having to apply inner dressings. Disadvantages include their price and the fact that they have to be removed. The most commonly used type is the Reuter type bivalve septal splint, made from silicone. Sheets of medical grade silicone or fluorplastic may be used to prevent synechiae and to keep a reconstructed nasal valve or vestibule open. In patients with a symptomatic septal perforation that cannot be closed surgically, the defect may be obturated with a silicone septal prosthesis or septal button (Fig. 10.5; see also Chapter 5, p. 192ff). Nowadays, various biological materials are commercially available, in particular cortical and cancellous bone, fascia, and pericardium. The materials marketed by Tutoplast Bioimplants (Tutogen Medical, Neunkirchen, Germany) are processed allografts of donated human tissue and bovine pericardium. Cancellous chips or blocks may be implanted submucosally to narrow a too wide nasal cavity (see Chapter 8, p. 289). Fascia or pericardium may used for augmentation and repair of defects. The quality and success of a surgical intervention depends mainly on the following factors: analysis of the pathological condition; surgical concept; skill of the surgeon, anesthesiologist, and surgical assistants; and quality of the instruments. Since the beginning of modern surgery in the 1880s, hundreds of instruments for nasal surgery have been designed. More than 50 authors have contributed to their development. Often, their names are still linked to the instruments they have introduced or popularized. However, most of the tools currently in use are no longer identical to their original designs. Generally, major and minor changes have been made by other surgeons and instrument makers. Nonetheless, in many cases the name of the originator is still linked to the instrument, largely for practical reasons. During surgery, for example, it is simpler to ask for a “Graig” than for a “heavy, biting septum forceps.” A side effect of this custom is that younger generations become familiar with the names of some of the pioneers in nasal surgery. The discussion and illustrations in this chapter only deal with the instruments used in the departments in Utrecht (the Netherlands) and Ulm (Germany). The authors are fully aware of the fact that many other valuable and effective instruments are available. “Tous les moyens sont bons quand ils sont efficaces”. (All means are fine as long as they are effective) Jean-Paul Sartre. Before surgery is started, the vestibules are cleansed and disinfected and the vibrissae are cut and removed. This procedure is carried out at the operating table either before or after induction of anesthesia. The cut-off vibrissae are removed using cotton-wool applicators with some Vaseline. Small strips of gauze are dipped into alcohol 80% to disinfect the vestibules and valve areas. Regarding the technique of local anesthesia and vasoconstriction, the reader is referred to Chapter 3 (p. 119ff). Fig. 10.7 Instruments for local anesthesia and vasoconstriction. a Six cotton-wool applicators. b Cotton wool. c Small cup with 200 mg crystalline cocaine. d Small cup with 15 drops of adrenaline 0.1%. Fig. 10.8a Short, broad speculum (Hartmann–Vienna type). b Narrow, medium-long speculum (Cottle). Fig. 10.8c Medium-long speculum (Killian). d Long speculum (Killian). Fig. 10.10 Disposable blades Fig. 10.12a-c Retractors: a alar retractor (alar protector); b short, angulated retractor (Aufricht); c long, angulated retractor (Aufricht). Fig. 10.12d–f Retractors: d uneven, four-pronged, blunt retractor (Cottle); e double retractor (Neivert); f double retractor (Aiach). Alar retractor (protector) to:

Materials

Sutures

Sutures

Resorbable Materials

Slowly Resorbable Materials

Nonresorbable Materials

Internal Dressings

Internal Dressings

Materials

Tapes

Tapes

Materials

External Splints (Stents)

External Splints (Stents)

Materials

Usually six layers are used. They are cut to the required size and shape with heavy scissors.

Septal Splints

Septal Splints

Materials

Intranasal Sheets

Intranasal Sheets

Materials

Septal Prosthesis (Septal Button)

Septal Prosthesis (Septal Button)

Materials

Commercially Available Biological Materials

Commercially Available Biological Materials

Instruments

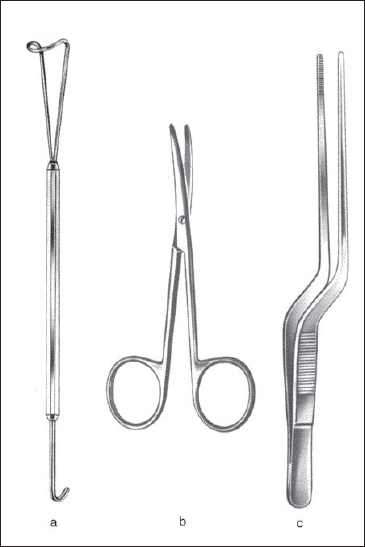

Instruments for Cleansing the Vestibules and Trimming the Vibrissae (“Trim Set”) (Figs. 10.6a–c)

Instruments for Cleansing the Vestibules and Trimming the Vibrissae (“Trim Set”) (Figs. 10.6a–c)

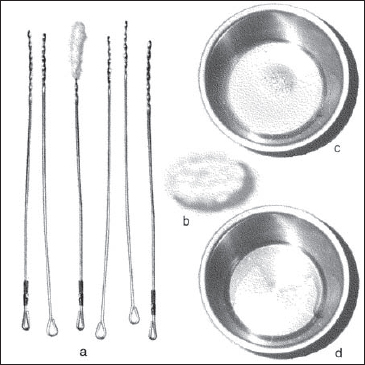

Instruments and Medications for Anesthesia and Vasoconstriction (Figs. 10.7a–d)

Instruments and Medications for Anesthesia and Vasoconstriction (Figs. 10.7a–d)

Local Anesthesia

General Anesthesia

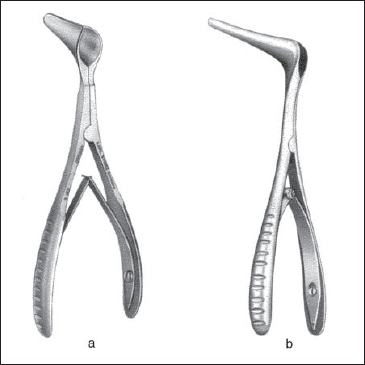

Specula (Figs. 10.8a–d)

Specula (Figs. 10.8a–d)

Classic short speculum used for inspection, infiltration anesthesia, and incision of the vestibule.

Medium-sized speculum with narrow blades used to expose the anterior nasal spine and premaxilla and to elevate inferior tunnels.

Speculum with medium-long blades used for surgery of the anterior part of the septum, turbinates, and nasal cavity.

Speculum with long blades used for surgery of the posterior part of the septum, turbinates, and nasal cavity.

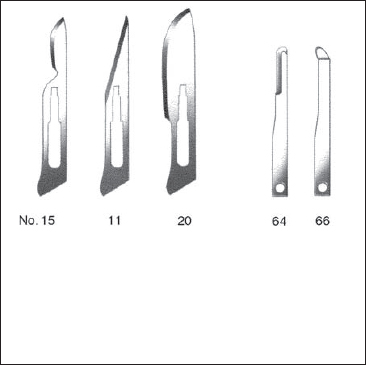

Knives

Knives

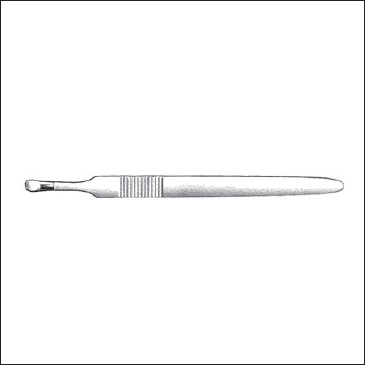

Handles (Figs. 10.9a–c)

Blades (Fig. 10.10)

Special Knives

Retractors (Figs. 10.12a–f)

Retractors (Figs. 10.12a–f)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree