CONGENITAL ANOMALIES OF THE LACRIMAL SYSTEM

Dale R. Meyer, John L. Wobig, and Roger A. Dailey

Understanding the embryology of the lacrimal system enables us to know what anatomical obstructions may occur. Congenital obstruction of the lacrimal system is present in up to 8% of newborns. Treatments for congenital obstructions are usually not difficult. The treatment should be definitive so as to avoid multiple anesthetics. Treatment depends on the family deciding between medical management and probing. Early probing is done because the risk is minimal and success of a cure is greatest at this stage. Medical management is chosen by some because 90% of obstructions will resolve within 13 months of age.

EMBRYOLOGY

The embryonic anlage of the lacrimal apparatus appears in the naso-optic groove at about the end of the second fetal month. Its position can sometimes be seen as a “birth mark”: a round spot with slightly different pigmentation than the surrounding skin, ~ 5 to 10 mm beneath and medial to the punctum of the lower eyelid. It also appears as a “dimple” or patent end of a supernumerary duct, which will be described later.

SECRETORY SYSTEM

The part of the lacrimal apparatus that forms the secretory system migrates laterally, to the upper and outer conjunctival side of the upper eyelid. A few glands acquire parasympathetic efferent innervation and form the main lacrimal gland and the accessory palpebral gland.

Other glands spread into the conjunctiva to form the accessory lacrimal glands of Krause and Wolfring.

Congenital Secretory Anomalies

Rarely, an anomalous lacrimal secretory duct is found opening on the cutaneous surface of the upper eyelid. A secretory duct (or ducts) is sometimes diverted into a bulbar conjunctival nevus or dermoid.

EXCRETORY SYSTEM

The part that becomes the excretory system is buried by infolding under its anlage and forms a rod of epithelial cells that migrate into the lacrimal fossa area. The end of the rod begins to enlarge to form the tear sac that in turn gives off a “pseudopod” superiorly, which divides into two columns that grow into the eyelid margins. The rod of cells from the anlage then involutes and disappears. Soon after the rods develop, canalization begins, first in the tear sac, then in the canaliculi, and last in the nasolacrimal duct, which is completed at about the time of birth.

Schwarz found that in ~ 30% of newborn infants the duct is still closed. In premature infants, the incidence of closed ducts is much higher. Apparently, the last barrier to canalization is the fibrous layer of the nasal mucoperiosteum. We will consider this a normal event unless it fails to open within the first 2 or 3 postpartum weeks.

Comparative Anatomy

The aquatic mammals, and also the hippopotamus and elephant, have no lacrimal excretory passages. There is a single canaliculus in the sheep, pig, rabbit, deer, and probably some other vertebrates. Most vertebrates, like the primates, have a canaliculus in each eyelid.

Congenital Excretory Anomalies

Congenital excretory anomalies occur in many forms and often have hereditary patterns. Ask and von de Hoeve stated that many abnormalities are due to amniotic bands that prevent normal development of various parts of the ducts and tear sac. However, more recent studies have indicated that there is a genetic basis for all the anomalies.

In one group of three siblings we have treated, the oldest child had no ducts on the right, and on the left, a functioning excretory system minus a lower canaliculus. The middle sibling had no ducts on the left and a functioning system minus an upper canaliculus on the right. The last sibling had no ducts on either side. No predecessor in the family with lacrimal anomalies could be found. There were no other children in the family.

Multiple puncta are often seen. Some open into the canaliculus medial to the main punctum and some have a double canaliculus in the lacrimal margin of the eyelid. The secretory system is usually present.

The anomalies that occur most frequently and produce the most symptoms are in the nasolacrimal duct. Summerskill reported that 22% of all dacryostenoses are in infants and are found in the nasolacrimal duct. Most of these ducts open spontaneously during the first 2 weeks after birth.

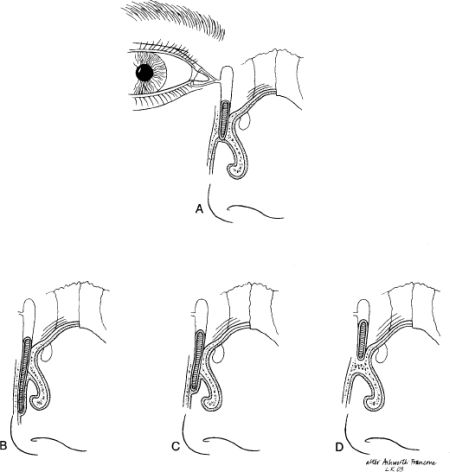

Eight types of variation are seen in the lower end of the nasolacrimal duct in congenital obstructions (Fig. 11-1A-D):

1. The duct that ends at or near the vault of the anterior end of the inferior nasal meatus and fails to perforate the nasal mucosa (by far the most common variation) (Fig. 11-1A)

2. The duct that extends clear to the floor of the nose lateral to the nasal mucosae (Fig. 11-1B)

3. The duct that extends several millimeters down lateral to the nasal mucosa without an opening (Fig. 11-1C)

4. An almost complete absence of a duct due to failure of the osseous nasolacrimal canal to form, frequently seen in cleft palate children (Fig. 11-1D)

5. A blockage of the lower end of the duct due to an impacted anterior end of the inferior turbinate

6. The duct that ends blindly in the anterior end of the inferior turbinate

7. The duct that ends blindly in the medial wall of the maxillary sinus

8. A bony nasolacrimal canal that may extend to the floor of the nose without an opening

Congenital anomalies of the motor mechanism occasionally occur even when the lacrimal passages are normal. There may be paralysis of the entire orbicularis oculi muscle or of only the medial ends of the palpebral parts. There may be failure of the muscle fibers to develop medial to the medial ends of the tarsi. In one patient, a sequestered part of the bony ethmoid labyrinth had cut through the posterior wall of the tear sac and produced an acute cellulitis. In another patient, a 3-month-old infant with severe dacryocystitis, the medial canthal area was opened at surgery. The tear sac had become the lining of the maxillary sinus. The common canaliculus was sticking out like a spout in the upper part of the sinus.

Congenital Lacrimal Amniotocele

We have observed several cases of a congenital condition that, to our knowledge, has never been named. We suggest that it be called congenital lacrimal amniotocele. The anatomical background for this entity is as follows.

In ~ 10% of the population, the canaliculi, instead of ending medially in the common canaliculus, end in the sinus of Maier (Schaeffer) into which they open separately. The sinus enters the tear sac at an acute angle. The posterior margin of this opening into the sac is called the valve of RosenMüller. In every case of acute or chronic swelling of the tear sac, and occasionally in the newborn infant, this valve prevents escape of fluid from the lacrimal sac back into the conjunctival sac. However, this condition never develops unless the nasolacrimal duct has failed to open.

When the obstetrician first notices at birth an enlargement at the medial canthus, the “amniotocele” is still sterile. Within a very short time, however, it becomes infected. The unsterile fluid in the conjunctival sac is pumped into the lacrimal sac when the eyelids close and cannot return to the conjunctival sac because the valve of RosenMüller locks it in.

TREATMENT OF CONGENITALLY CLOSED NASOLACRIMAL DUCTS

With the possible exception of premature infants, there seems to be no age limit for treatment of these abnormalities, provided that the physician produces minimal trauma during surgical manipulations. No matter the patient’s age, the canalicular epithelium should always be handled with the gentleness and respect accorded all intraocular structures during surgery. Except at the point of obstruction in the inferior meatus of the nose, the use of force during probing is contraindicated.

The earlier the obstruction is removed, the higher is the incidence of cure because the vigor and growth of the lacrimal epithelium are probably greatest at birth; as the tissues mature, vigor and growth gradually diminish. Also, the more chronic the infection and the greater the fibrotic and inflammatory changes, the more difficult it is to prevent recurrence.

EVALUATION

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree