CHAPTER 31 Ankle Instability and Impingement Syndromes

LATERAL ANKLE LIGAMENT RECONSTRUCTION

The triad of recurrent ankle sprains, heel varus, and stress fracture of the fifth metatarsal should always be taken into consideration when treatment is planned in the sedentary or athletic patient (Figure 31-1). The case illustrated in Figure 31-1 represents a good example of failure of treatment if the underlying biomechanical and anatomic process is ignored. A calcaneus osteotomy, in addition to a stronger ankle ligament repair, which might have prevented the subsequent problems, would have provided improved correction. An ankle ligament reconstruction can be performed without correcting the heel varus, but the outcome will depend on the flexibility of the subtalar joint and presence of additional symptoms.

Operation Selection

Ankle ligament reconstruction in the high-performance athlete must be approached differently. The peroneal tendon should not be sacrificed as part of a reconstructive procedure, and even using a strip of the peroneus brevis tendon is not warranted in the high-performance athlete. In this context, high performance refers also to the gymnast, the ballet dancer, and other athletes for whom pivoting on the pointed foot is important. If a patient has gross ankle instability and an anatomic repair is not thought to be sufficient, then augmentation of this anatomic repair with a hamstring graft can be performed. Under these circumstances, my preference is to perform a percutaneous hamstring allograft procedure in these athletes and not to resort to an open procedure.

In the patient with intraarticular ankle disease, the timing of the surgery is always a concern. For example, if an osteochondral defect requiring treatment is present, how should this operation be performed, in addition to ankle ligament reconstruction? (Figure 31-2). In patients with such defects, ankle arthroscopy, in conjunction with the ligament reconstruction, is recommended.

Nonetheless, it is something to consider when combined diseases are addressed. The other issue pertaining to the intraarticular disease concerns the type of reconstructive procedure used. After ankle arthroscopy, interstitial tissue edema is always present, with fluid leakage into the soft tissues, and finding the correct anatomic plane—for example, for reconstruction using a Broström procedure—can be more difficult because of the tissue edema. I do not believe that performing an ankle arthroscopy is necessary in the absence of intraarticular disease or symptoms of ankle pain.

The Broström Procedure

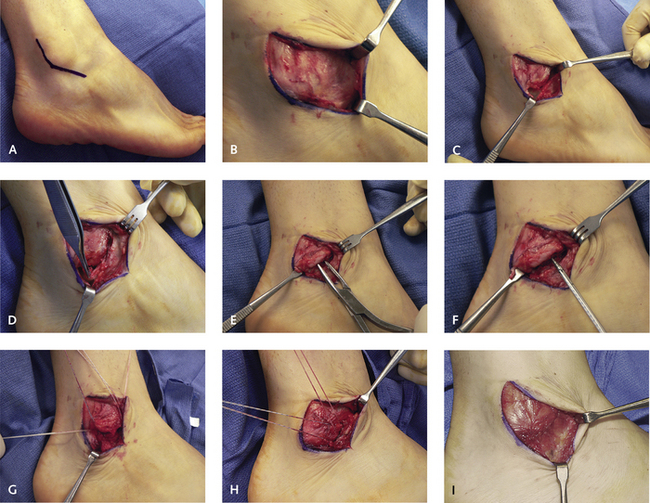

I do not use the traditional “hockey stick”, or J-type, incision for the Broström procedure, because it does not permit visualization of the peroneal tendons. I use a more longitudinal incision located over the anterior fibula, inspecting the peroneal tendon simultaneously and facilitating repair of the calcaneal fibular ligament (Figure 31-3). This incision affords ready access to the anterior ankle and can even be extended to perform an open cheilectomy.

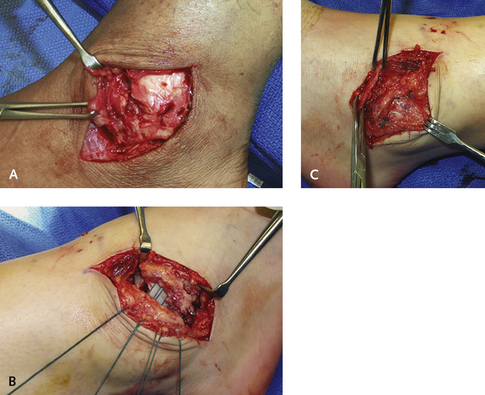

Care must be taken to avoid the superficial peroneal nerve anteriorly in the terminal portion of the incision. The soft tissue is reflected and the extensor retinaculum identified as a separate layer before the ankle joint is opened. This extensor retinaculum can be used to strengthen the anatomic repair (Figure 31-4). The inferior root of the extensor retinaculum inserts into the neck of the calcaneus just anterior to the subtalar joint, and can be used to stabilize both the ankle and subtalar joints in cases of combined instability.

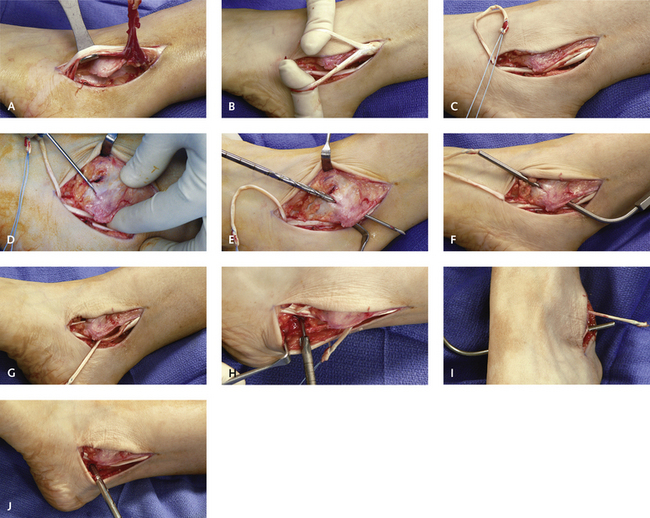

Modification of the Chrisman-Snook Procedure

The original description of the Chrisman-Snook procedure included a long strip of the peroneus brevis tendon, which was split in half and placed through a bone tunnel in the calcaneus. This aspect of the technique is not necessary because a short strip of the anterior third of the peroneus brevis tendon is sufficient. The incision is made paralleling the peroneal tendons and extending for no more than 6 cm proximal to the tip of the fibula. The length of tendon that is required should be measured before the tendon is cut proximally, but rarely exceeds approximately 8 cm. The advantage of this procedure is that it can be used in the presence of a severe tear of the peroneus brevis tendon, for which a split portion of the tendon can be incorporated and used for the ligament reconstruction. Splits in the peroneus brevis tendon are common in combination with recurrent ankle instability, and if these splits are present, this portion of the tendon is then cut proximally and used for the reconstruction (Figure 31-5).