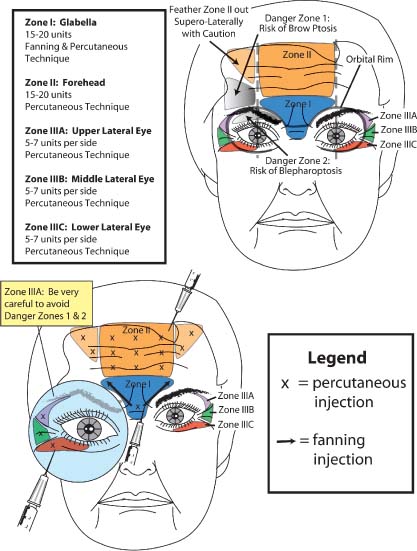

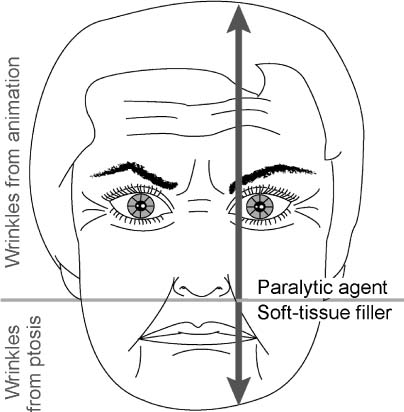

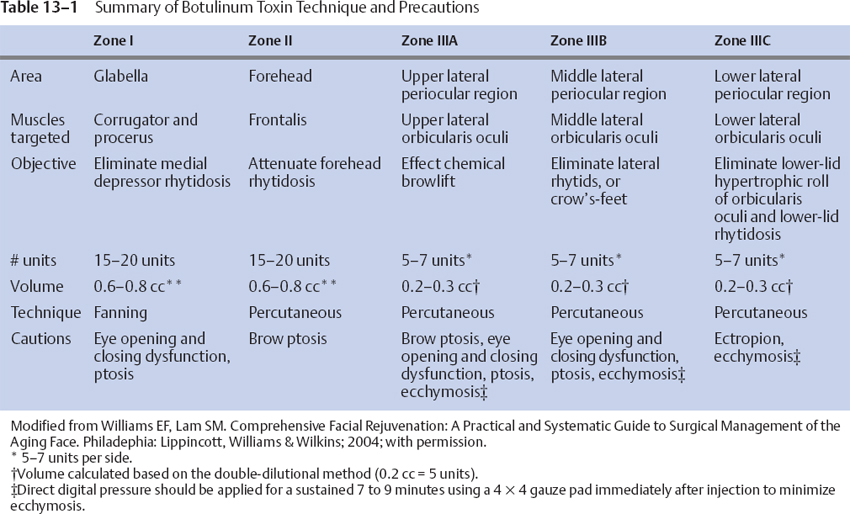

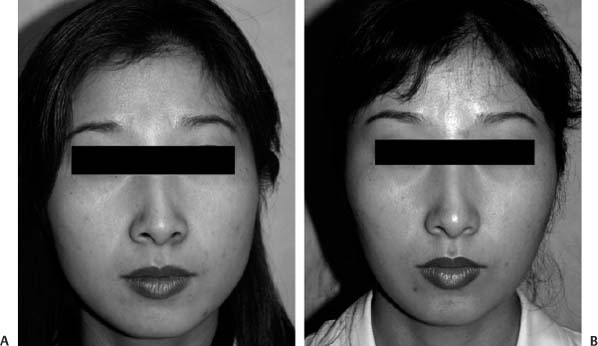

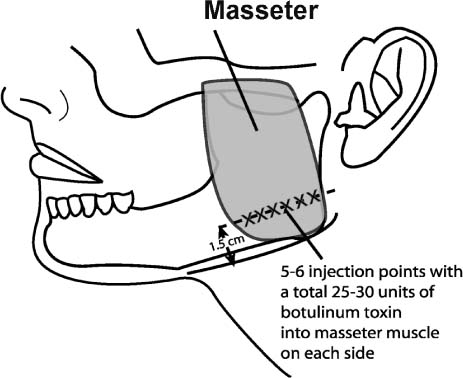

13 The first edition of this book covered the subject of miscellaneous cosmetic surgical procedures in a single, cursory chapter. The original chapter discussed both minor operative procedures and various resurfacing techniques that were suitable for the Asian face. Since publication of that edition, the field of facial plastic surgery has undergone a veritable explosion. Surgical advances have been made that enable the patient to undergo a more natural surgical rejuvenation or modification with less recovery time. As part of this movement toward minimally invasive surgery, a byzantine array of minor techniques, soft-tissue augmentation materials, and paralytic agents have arisen to meet the demand of the “quick fix” mindset. Furthermore, resurfacing techniques have now embraced both newer modalities (laser ablation, coblation, nonablation) and more traditional methods (dermabrasion and chemical peels). What constitutes an ancillary procedure is an ill-defined entity and reflects this author’s construct of this proposed subject. This chapter will endeavor to cover disparate, minor procedures that can be performed in the office setting without sedation, that is, botulinum toxin (Botox, Allergan, Irvine, CA), soft-tissue fillers, lip reduction, dimple fabrication, and micropigmentation, particularly for the Asian patient, excluding implants and resurfacing, which have their own dedicated chapters. As mentioned, many different techniques and materials have expanded the surgeon’s armamentarium to address a host of minor aesthetic flaws in the office setting. Among these soft-tissue fillers and chemical agents, only a few have met approval by the Food and Drug Administration for use in the United States, where both authors practice. Therefore, the experimental and foreign ancillary materials will not be addressed in this chapter. The characteristic anatomy of the Asian face and the particular aging process that the Asian face undergoes have been covered in detail elsewhere in this book. However, a few salient points that are applicable to the decision-making process necessary for the implementation of adjunctive procedures are reviewed here. The more pigmented Asian skin may be relatively recalcitrant to photoaging. Although rhytidosis is a less prevalent phenomenon, the more poorly defined skeletal structure, more substantial facial adipose accumulation, and thicker soft-tissue envelope predispose toward increased gravitational descent of the buccal region. Therefore, soft-tissue augmentation along the nasolabial and labiomandibular folds deserves special attention. In this chapter, proper use of various injectable soft-tissue fillers will be reviewed. Liquid injectables serve a particularly important role in the management of the Asian face, as implantation of solid materials that require discrete incisions may remain conspicuous for an unacceptably protracted time in the Asian skin that is predisposed toward erythema, hypertrophic scarring, and hyper- and hypopigmentation. Although fine panfacial rhytidosis may be less prevalent in Asian populations, periocular rhytids and brow ptosis, both amenable to botulinum toxin (BTX) in certain situations, are quite common and will also be discussed. A simplified algorithm for selection of BTX and injectable soft-tissue fillers as well as details in proper injection technique will be reviewed. Another ancillary procedure that merits discussion concerns surgical lip reduction. As most Caucasians complain of hypoplastic lips, especially as maturity accentuates this deficiency, certain Asian populations (e.g., southern, Malaysian, and Polynesian ethnicities) exhibit a characteristic lip protuberance, which they at times perceive as an unbecoming attribute. Partly, motivation for surgical intervention may be derived from the inclination to soften this overly ethnic feature. Overall, Asian demand for this procedure falls far short of the frequency with which darker-complected individuals of African descent seek this form of surgery. Generally, the more conservative and common request is for only lower-lip modification, although this procedure paired with an upper-lip reduction is not altogether rare. Isolated upper-lip reduction has also been sought as an independent procedure. Another procedure that is far more commonly requested in Asia is the fabrication of a dimple. Besides the aesthetic charm that this entity imparts, many Asians traditionally consider the dimple a sign of good fortune. In fact, dimples that fall in various regions around the mouth have unique appellations that correspond to the degree of good favor that a particular location on the face bestows. The surgical creation of one or more dimples is a relatively simple, straightforward endeavor that can be performed in the office setting and designed according to the patient’s precise aesthetic criteria. Finally, the prevalence of micropigmentation, or cosmetic tattooing, far exceeds that of Caucasian societies. Although this technique has been increasingly relegated to lay technicians, often justifiably so, the surgeon should comprehend the cultural dynamics and appreciate the technical aspects of the process to communicate more effectively with his or her Asian patients. Generally, a reasonable treatment strategy for adjunctive procedures such as BTX and soft-tissue injectable fillers divides the face vertically into two halves via an imaginary horizontal line drawn through the base of the nose (Fig. 13-1). BTX therapy is particularly well suited for early wrinkles present in animation above this line but may be less appropriate for wrinkles below this line. Perioral BTX therapy for an overactive depressor offers limited benefit with the attendant risk of oral incompetence. An exception to this rule that will be discussed in this chapter concerns the reduction of masseteric hypertrophy with BTX for lower facial contouring, an aesthetic objective that is more commonly sought in the Asian population. This unique application of BTX therapy has achieved particularly widespread implementation in Korea but was first reported in the British literature in 1994.1 This use of BTX violates the horizontal line principle, as it concerns a distinct aesthetic pathology, masseteric hypertrophy, as opposed to its more conventional use of wrinkle effacement. With the foregoing exception in mind, soft-tissue augmentation is the preferred method of addressing the lower half of the face rather than with BTX. A fundamental difference in wrinkle quality above versus below this line explains this author’s rationale for the strategy. Wrinkles that form above this line are generally etched-in lines from repeated motion and benefit from either BTX therapy early (incipient lines) or resurfacing later (mature lines). Deeper glabellar lines may also be appropriately excised if very advanced. Solid or liquid soft-tissue augmentation in the periocular region cannot readily and evenly efface the fine, etched-in lines in this region. Although the glabella tolerates this type of augmentation, many liquid fillers are contraindicated due to skin necrosis and retrograde thrombosis and blindness; and solid augmentation may not be the best modality to treat this area (consider either resurfacing or excision as better alternatives). Figure 13-1 Illustration shows the benefit of adjunctive procedures based on an imaginary line drawn through the nasal base. Wrinkles above this line are typically attributed to animation, whereas, below this line, wrinkles develop principally due to tissue descent. Accordingly, botulinum toxin (BTX) is well suited to address incipient or early wrinkles above this horizontal line; and an appropriate soft-tissue filler is preferable to augment the ptotic tissues below the line. Although BTX has been successfully used below this line, and a filler, above this line, the author believes that the risk outweighs the benefits (refer to text for further details). (Adapted from Williams EF, Lam SM. Comprehensive Facial Rejuvenation: A Practical and Systematic Guide to Surgical Management of the Aging Face. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2004; with permission.) Below this horizontal axis, the lines that develop (e.g., the nasolabial and labiomandibular folds) usually do so due to gravitational ptosis. These folds, rather than wrinkles, are more amenable to soft-tissue augmentation with either liquid or solid fillers than BTX therapy. The one exception to this rule is the perioral rhagades, or smoker’s lines. These fine crevices around the mouth are more akin to the fine lines that circumscribe the eye. Therefore, solid or liquid augmentation of these lines is not as effective but still possible for some limited improvement (a limitation that the patient should well comprehend beforehand). Unlike the periocular rhytids, however, the perioral rhagades are not as amenable to BTX (which may be an apparent caveat) but should be treated with laser ablation, coblation, or dermabrasion. Hypoplastic lips, in contrast, may be appropriately treated with soft-tissue augmentation materials like the other areas described below this horizontal axis, but augmentation is less often requested in the far Southeast Asian patient for the previously enumerated reasons. Besides the anatomic differences between the Asian and Caucasian faces, BTX and soft-tissue filler injection techniques differ little but should be well understood to ensure maximal aesthetic benefit and minimal risk of adverse outcome. This section on use of botulinum toxin is divided into two principal parts: management of facial wrinkles and management of masseteric hypertrophy. Although treatment of facial rhytidosis represents a common indication for BTX therapy, this chapter endeavors to present a systematic approach that has been clinically useful irrespective of race and ethnicity. The latter technique of masseteric reduction may also be applied to Caucasians and other races who should desire this type of intervention, but generally it is reserved for Asian patients who request this procedure. The first step that is required before BTX can be used is reconstitution of the lyophilized concentrate. Typically, 2 to 2.5 cc of saline is recommended for each bottle of 100 U of BTX. This dilution yields an approximate concentration of 5 units per 0.1 cc. The authors recommend a double-dilution method of 4 cc of saline for each bottle of BTX to yield a concentration of 5 units per 0.2 cc. This dilution permits a more even distribution of toxin across the intended muscle, particularly in the forehead region. Furthermore, maximal yield of toxin is more easily obtained with this greater dilution, as minor, inadvertent toxin spillage during administration and recovery of remaining toxin from the bottle are less problematic with this more dilute concentration. The reader is cautioned that further dilution of toxin has two potential drawbacks (and is not advised): unintended migration of toxin to adjacent muscles due to higher injected volume amounts and loss of toxin activity (with a fourfold or greater dilution). The side effect of using this decreased concentration (and therefore higher volume) is the potential increased postinjection edema and ecchymosis from the volume effect. Nevertheless, appropriate application of ice packs prior to injection and local pressure after injection minimize the likelihood of this sequela significantly. One further comment is warranted: the amount of BTX needed for masseteric reduction (25 to 30 units per side, which equals 1 to 1.2 cc of volume based on the double-dilution method) may lead to slightly more edema postinjection with the less concentrated BTX than would be encountered with the conventional concentration. Accordingly, if an entire bottle will be dedicated for use of masseteric reduction, then the single-dilution method may be justified. The reader is advised to use his or her own discretion when deciding the appropriate dilution. Reconstitution of the dehydrated solid may be a relatively straightforward affair, but a few remarks will be made as to optimal technique so as to minimize potential waste and to enhance ease of use. A 5 cc syringe outfitted with an 18-gauge needle should be used to withdraw 4 cc of saline, which in turn is injected into the BTX bottle. The reconstituted BTX solution should be gently swirled, as shaking the bottle can deactivate toxin activity. A 1 cc syringe with an 18-gauge needle can be used to draw up the solution for clinical use. After the solution has been drawn into the syringe, the bottle should be turned back upright, the hub of the syringe drawn back slightly until the fluid is completely withdrawn from the needle into the syringe, and the syringe is then detached from the needle (with the needle remaining in the top of the bottle to load the next syringe). A 1/2 inch, 30-gauge needle can then be placed onto the syringe for injection. Use of separate syringes drawn up with the appropriate amount of toxin for each particular area of injection (e.g., glabellar and forehead) facilitates an easy method to keep track of how much toxin should be injected into each muscle area. A few general principles of BTX therapy will also be elaborated before a detailed discussion of clinical application. First, the intended area of treatment should receive 3 to 5 minutes of direct ice-pack application immediately prior to injection to anesthetize the area, decrease postinjection edema, and enhance vasoconstriction and thereby limit postinjection ecchymosis. An alcohol preparatory pad should not be used, as the alcohol can serve to render the toxin inactive. If used, the alcohol should be entirely evaporated before toxin injection. After injection, local pressure should be applied steadily without interruption for 7 to 10 minutes with a gauze pad, especially in the periocular region, which is predisposed toward greater ecchymosis than the forehead and the glabella. After injection, the patient should remain upright for a minimum of 1 to 2 hours and should not massage or manipulate the area to avoid spreading the toxin to unintended areas. Minimizing exercise and alcohol intake for the first few hours has also been reported to avoid the likelihood of a complication. New evidence supports the finding that the toxin binds to the target muscle in less than 90 minutes, making these behavioral modifications theoretically unnecessary beyond this short time period. The patient should be advised that BTX requires a full 7 days to witness its complete therapeutic effect but may begin to be evident as early as 3 days postinjection. The patient is routinely called 7 days after injection to increase rapport and to ensure that the BTX has taken effect to the patient’s satisfaction. Preoperative photographs are also advised to document improvement if the patient testifies to the contrary. This section will present a systematic method of BTX injection for the upper half of the face. The upper facial area is divided into three principal zones: zone I, the glabella; zone II, the forehead; and zone III, the periocular region (Fig. 13-2; Table 13-1).2 Each of these zones will be discussed separately in terms of clinical indications, recommended toxin amount, injection method, and avoidance of danger zones. Zone I represents the cluster of depressor muscles located in the glabellar region. The corrugator muscle extends over the medial eyebrow and merges medially in the central glabellar region, with overactivity of this muscle leading to vertical rhytids in this area. The procerus muscle that runs more medially in a vertical direction contributes to the lower horizontal rhytids. Patients who suffer from this type of rhytidosis typically appear angry or tired and often strike this pose out of habit. BTX therapy can arrest this behavior by blocking this unwanted expression. Accordingly, even though BTX is unequivocally temporary in its effect, repeated treatments may serve to break the cycle of unintended (or intended) frowning, and the patient may ultimately forget about engaging in the habit of frowning. Therefore, the benefit of BTX in this area may at times be considered “permanent” for this facial zone, so long as what that means exactly is conveyed to the patient. A total of 15 to 20 units (0.6 to 0.8 cc) is required to efface the wrinkles of animation in this area. The patient should be asked to squint and frown to reproduce the target wrinkles prior to injection. Care must be taken to avoid toxin spread over the orbital rim, which might lead to blepharoptosis. Accordingly, all injections should be aimed superiorly (from inferomedial to superolateral) so that toxin migration will be away from the orbital rim (Fig. 13-2). Because the corrugators lie deep adjacent to the bone, a deeper injection is warranted for more definitive paralysis. Using the nondominant hand, the supraorbital notch is depressed during the injection, and the corrugator is pinched between the forefinger and thumb for several reasons. First, digital pressure along the orbital rim will serve as a physical barrier for toxin migration toward the levator muscle. Second, the supraorbital nerve can be depressed and the muscle belly pinched between the forefinger and thumb (as a form of distraction) to help alleviate the discomfort associated with the deeper injection. Third, pinching the muscle belly facilitates a deeper injection. The toxin is injected during needle withdrawal. Additional toxin can be placed percutaneously in the midline to improve the procerus muscle, depending on the extent of horizontal rhytidosis. Figure 13-2 Illustration shows the three zones for BTX injection. Zone I is defined as the glabellar region; zone II is the forehead; and zone III refers to the lateral-canthal region, which in turn is subdivided into vertical thirds (zones III A, B, C). The two danger zones to be avoided are the upper-eyelid region (which can lead to blepharoptosis) and the lateral-brow region (which can lead to brow ptosis). Zone II should be feathered carefully superolaterally to avoid the risk of brow ptosis. Preferred injection amounts and techniques are also shown. (Adapted from Williams EF, Lam SM. Comprehensive Facial Rejuvenation: A Practical and Systematic Guide to Surgical Management of the Aging Face. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2004; with permission.) Zone II refers to the frontalis muscle that spans across the central forehead. Injection should be uniform and remain principally medial to the midpupil to avoid the risk of lateral brow ptosis (danger zone 1). However, injection can fan superolaterally toward the lateral brow extent with caution, remaining at a minimum of one or two fingerbreadths above the orbital rim. Very little toxin should be placed lateral to the midpupillary line during the initial BTX session to avoid the risk of brow ptosis that may occur, particularly in older individuals with a weak frontalis muscle laterally or in women who cannot tolerate any degree of brow descent or in those who desire some brow elevation.* A careful history that delves into the patient’s prior BTX experience will gain useful insight into the precise distribution and amount of toxin that will provide safe and efficacious therapy. Because the muscle extends over a large expanse of territory, the fanning technique is an ineffective method of covering the entire central forehead. Accordingly, the percutaneous technique (Fig. 13-2) should be used in a symmetrical fashion. As the patient is asked to elevate his or her forehead, the areas of concentrated muscle activity should be addressed with the injection. Typically, 15 to 20 units (0.6 to 0.8 cc) are required to address the forehead wrinkles. A broader forehead may require proportionately more BTX, and a diminutive forehead, less. In the preoperative setting, the patient is informed that the inferolateral wrinkles will not be ameliorated so as to avoid the risk of brow ptosis. For the forehead, a marking pen may be a helpful tool to delineate all of the points to be injected to ensure symmetry and precision. A Sharpie permanent marker is preferred to gentian violet, as it can be easily erased after the treatment session with alcohol. Use of a marking pen also helps the physician establish dialogue with the patient about the intended areas for injection. Injection superior and inferior to a particular rhytid rather than directly over one has the theoretical advantage of more completely targeting the particular muscle responsible for the rhytid, but excellent results are still attainable by injecting over the wrinkle itself. Zone III is divided in turn into three subzones: zone IIIA, the upper lateral periocular region; zone IIIB, the middle lateral periocular region; and zone IIIC, the lower lateral periocular region. Each of these subzones can be treated with 5 to 7 units (0.2 to 0.3 cc) per side to effect maximal benefit. However, 5 to 7 units can also be distributed more widely if less rhytidosis is present. Zone IIIA extends just inferior to the hairy eyebrow and just along the orbital rim that corresponds to the superolateral aspect of the orbicularis oculi muscle. Injection of this area with BTX effects a chemical brow lift by partially blocking the depressor function of the orbicularis oculi muscle to permit unopposed brow elevation of the frontalis muscle (Fig. 13-3A,B). Care should be taken to avoid too medial or inferior an injection that could predispose toward onset of blepharoptosis or too superior an injection that could lead to brow ptosis; this narrow isthmus must be cautiously navigated. The patient also should be advised in advance that a chemical brow lift may not be effective in every patient, particularly the older individual who has a less vigorous frontalis muscle to lift the brow upwards. If the patient is fully cognizant of this potential limitation, then BTX therapy can proceed. Also, if the patient has an asymmetric brow, BTX can be injected more superiorly in the lateral tail of the eyebrow on the descended side in an attempt to raise this side to match the more superiorly positioned contralateral side. Figure 13-3 (A,B) This 23-year-old Vietnamese woman shows a congenially heavy brow that imparts a tired expression to her face. She also exhibits a corrugated appearance to her forehead region that is attributable to an overactive frontalis muscle. She had BTX therapy performed in zone II alone by another physician in the past and subsequently developed significant brow ptosis. Most likely, injection technique was correct, but her entire brow was drawn downward due to a very strong depressor muscle complex. She underwent injection of zones I, II, and IIIA and is shown 2 weeks after injection with notable improvement in her forehead muscle activity and maintenance of her brow position. She also appears more awake due to the chemical brow lift imparted by injection of zone IIIA. Of note, she required additional injection of toxin farther laterally in zone I because her corrugator muscle extended over a wider distance than typically encountered, resulting in some residual rhytidosis upon frowning. Zone IIIB represents the midlateral extent of the orbicularis oculi that is evident as crow’s-feet in this area during smiling. When these wrinkles extend down to the lower-lid and upper-cheek region, then zone IIIC is also affected. Proper amount of BTX must be administered (5 to 7 units per side per subzone) to achieve complete ablation of these wrinkles. A hypertrophic orbicularis oculi roll that is evident along the lower lid (also part of zone IIIC) can be addressed with injection over the preseptal and pretarsal orbicularis muscle. Care should be taken to avoid injection along the lower-lid/upper-cheek region when two conditions should exist. First, a relatively lax lower lid may result in scleral show or frank ectropion if injected with BTX. Second, malar bags that are present due to a weakened orbicularis oculi can be exacerbated when injected with BTX. Furthermore, injection too far laterally or inferiorly can paralyze the zygomaticus muscle and compromise the patient’s smile. The patient should understand these limitations and relative contraindications before injection can be safely performed. Figure 13-4 (A,B) This 44-year-old Korean woman underwent 50 units of BTX and is shown 3 months after injection with good improvement in the contour of her jawline. Discussion of BTX use for the lower half of the face will be restricted to treatment of benign masseteric hypertrophy, which contributes to the unaesthetic appearance of a wide, square jaw. The ideal shape for the Asian face, particularly for the female, is an oval configuration (Figs. 13-4A,B, 13-5A,B). A prominent jawline is associated with an overly masculine and aggressive appearance that is often considered an unbecoming feature. However, men also seek reduction of a prominent jawline when this attribute appears to render the face wider and flatter in aspect. In general, the Asian face tends to be flatter and wider than the Caucasian model, and some Asians seek to reduce this ethnic appearance by softening the jawline and thereby reducing the effective girth of the face. Figure 13-5 (A,B) This 28-year-old Korean woman underwent one injection session with 50 units of BTX to reduce the square appearance of her jaw and is shown 10 months after one treatment with maintenance of her result. (From Park MY, Ahn KY, Jung DS. Botulinum toxin type A treatment for contouring of the lower face. Dermatol Surg 2003;29:477–483; with permission.) To determine the proper candidate for this technique, a relevant history and targeted physical examination should be performed prior to electing to proceed. A patient should be asked how long this feature has been present and whether it is related to any dental or temporomandibular joint problem (pain, clicking, etc.). A history of bruxism may also be elicited. These dental/orthodontic/orthognathic considerations may suggest that the patient be better served with a formal dental evaluation and consultation rather than or prior to BTX therapy. Chewing gum or the curious habit of cuttlefish chewing in Asia may also be contributing factors and can be curtailed to effect a change without BTX therapy. On physical examination, the anteroposterior view assumes the most important perspective. The patient should be evaluated with and without clenching the teeth, during which time the examiner carefully palpates the degree of masseteric activity. If the examiner feels a significant contribution of the masseter, the patient can be asked to palpate the examiner’s masseter as a point of comparison. The prominence of the bony angle should also be inspected both visually and by palpation. Based on this examination, the physician should decide on the relative contribution of the muscle and bone to the overall appearance of the jawline. The physician can then guide the patient regarding the relative benefit or lack thereof that BTX therapy will yield. If the patient requires more invasive skeletal reduction, then an osteotomy may be the preferred treatment of choice (refer to Chapter 12). Before undertaking BTX injection, the patient should be informed of the potential benefit and drawbacks of this technique. Clearly, the benefit would be a reduction of the masseter muscle, which will contribute to a softer oval contour of the mandibular angle. Also, unlike traditional BTX therapy, reports have indicated that the effect of this type of therapy may endure considerably longer, upwards of a year, compared with the 3 to 6 month window observed with conventional BTX administration.3,4 Injection in this area may also lead to potential side effects that include masticatory difficulty, speech disturbance, muscle ache, a relatively prominent zygoma, facial asymmetry, and facial nerve paresis. Although these complications are unlikely, they must be detailed to the patient in the preoperative setting. Along with these more serious problems, the patient should be informed as per routine that ecchymosis, swelling, and lack of efficacy could be observed. Prior to injection, the patient should be iced down thoroughly with an ice pack to minimize ecchymosis and edema after injection and to anesthetize the area prior to injection. A total of 25 to 30 units of toxin should be injected into each side of the face along five or six injection points that span horizontally across the muscle at a level ~1.5 cm above the jawline (Fig. 13-6). A standard 1 cc syringe outfitted with a 1/2 inch, 30-gauge needle can be used to perform this procedure. The patient should be asked to clench the jaw firmly throughout the procedure so that the muscle can be more readily identified and therefore targeted. It is safer to inject deeper into the muscle than superficially, which could potentially affect the facial nerve branch. Pressure application should be maintained for 5 to 10 minutes after injection to minimize swelling after injection. Figure 13-6 Illustration shows proper injection technique of BTX for masseteric reduction. A total of 25 to 30 units of toxin should be injected into each side of the face along five or six injection points that span horizontally across the muscle at a level ~1.5 cm above the jawline. The patient should be followed 1 week after surgery to determine that no complications have arisen. The physician can palpate the muscle at that time and feel that its strength has been attenuated somewhat. However, the aesthetic benefit will typically not be evident for 6 weeks. Park et al’s study found that the masseter continued to undergo atrophy on computed tomography (CT) scan for 3 months and on ultrasound for the first 1 month, and they further observed the persistence of the aesthetic benefit to endure in some patients for 10 months.4

Ancillary Procedures for the Asian Face

♦ General and Anatomic Considerations

♦ Botulinum Exotoxin A (Botox)

Botulinum Toxin Therapy for Management of Rhytidosis

Botulinum Toxin Therapy for Management of Masseteric Hypertrophy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree