| 1 | Anatomy and Analysis |

Rhinoplasty is among the most challenging of facial plastic surgical procedures. Not only is the nose the central aesthetic feature of the face, but also, if it is misshapen, a functional problem may compound the cosmetic distortion. Potential difficulties the surgeon might encounter in primary rhinoplasty are made only more challenging when the patient has already had one attempt at surgery.

Revision rhinoplasty is not simply a second surgery in the same anatomic location. At best, the patient wants a little better result than the one he or she was left with after one surgery. At worst, the patient is devastated by a crippling functional problem coupled with a deformity lying in the middle of the face. The high expectations the revision rhinoplasty patient places on the surgeon make accurate preoperative diagnosis imperative. The surgeon must have the skill to analyze a deformity, decide how to repair it, and have several alternatives available if the diagnosis is inaccurate or the technique of repair is suboptimal. Anatomic variations, already a challenge to the primary rhinoplasty surgeon, become hurdles of uncertainty the revision surgeon must overcome through accurate diagnosis and sound repair.

Although the techniques for analyzing an unoperated and a previously operated nose are the same, the underlying structure and anatomy may be vastly different. Proper correlation between analysis and aberrant anatomy will lead to more successful outcomes in revision rhinoplasty.

History

History

Patients seeking revision rhinoplasty tend to be highly selective in their choice of surgeon. Their revision surgery represents a significant financial, emotional, and time-consuming investment, and patients are naturally more apprehensive about their subsequent procedure. The surgeon must restore the patient’s confidence while mitigating realistic outcomes.

Each patient consulting for revision rhinoplasty has vastly different expectations; the surgeon should advise the patient about how pragmatic these expectations are. An open consultation will help the patient to understand the difficulty and degree of improvement in correcting specific nasal deformities. For example, a patient with an overly narrowed nostril sill caused by overly aggressive Weir excisions should be advised of the challenge that revision surgery represents.

During the interview, it is important to seek out not only aesthetic change but also functional issues. Often, patients with longstanding nasal obstruction do not realize their degree of nasal airflow impairment. This is especially true in patients with uncorrected septal deviations from previous surgeons and narrow internal valves.

Patients ideally should obtain before and after photographs for each nasal operation and the previous surgeon’s operative notes. Unfortunately, a previous rhinoplasty surgeon’s operative history may harbor gross inaccuracies and should only be used as a rough guide. Photographs may demonstrate a temporal relationship between the complication and when it occurred. An illustration of this is the dynamics of middle vault narrowing, which occurs gradually over a period of years rather than months. The patient’s pictorial record may demonstrate subsequent narrowing and coinciding nasal obstruction.

Physical Examination

Physical Examination

Correlation of the physical exam with controlled quality photographic stills of the patient will provide a better understanding of the patient’s residual nasal deformity. Each of these necessary diagnostic arms provides information that complements the other.

The thickness and character of the skin-soft tissue envelope (S-STE) should be determined. Patients with previous surgery may have extensive thinning of the skin, damage caused by extrusion of alloplastic implants, or significant scarring with thickening. Palpation of the S-STE will reveal the extent of damage and mobility of the skin, which may temper expectations of both patient and surgeon. For instance, in a patient seeking dorsal augmentation and added length to his nose, a severely scarred and contracted envelope will limit the amount of surgical improvement possible.

The bony pyramid is examined and palpated for asymmetries, irregularities, and width. The nasal dorsum should follow a gentle curving line from the medial brow to the tip.1 Persistent dorsal humps should be palpated to help identify their constitution. When the middle vault is examined, it is important to note any asymmetries, the width, deviations, and saddling. Collapse of the upper lateral cartilages (ULC) also should be noted. It is imperative to examine the dorsal septum in the middle vault area. Deviations in the middle vault can be caused by upper lateral cartilage depressions, dorsal septal deviations, or both.

The tip’s rotation, projection, and its relation to the dorsum are then evaluated. Domal asymmetries, fullness, depressions, and the overall shape of the nasal tip should be noted. Palpation of the cartilaginous framework is essential to diagnose the deformity. Tip strength should be determined to successfully plan the reconstruction of the medial and lateral tip components and determine the residual strength of the nasal base. The nasal–labial angle is examined next. Its contributions from the nasal spine and posterior septal angle should be palpated to distinguish soft tissue from cartilaginous excess. Although frequently overlooked, the position of the nasal tip also can contribute to nasal obstruction. Ptotic tips should be manually elevated to determine whether any improvement to the obstruction occurs.

The functional examination begins by watching the patient breathe. Does the patient breathe primarily through the mouth or the nose? When breathing through the nose, is there dynamic collapse with normal inspiration? When breathing more forcefully, which side collapses first or most severely?

The intranasal examination concentrates on each nasal functional subsection independently. The external nasal valves, septum, internal nasal valves, inferior turbinates, middle meatuses, and nasopharynx are examined serially. Inspection of the nasal septum for any residual deviations and contributions, if any, to dorsal deviations is performed. Any crusting must be removed to reveal the condition of the mucoperichondrium and possibility of occult nasal perforation. The presence of perforations should be noted and explained to the patient. Although perforations may be complications of previous surgeries, the patient’s social history should be reviewed to determine drug consumption. The septum may be palpated with a cotton tip applicator to help determine whether cartilage is present. In addition, both auricles should be palpated to determine the amount and character of residual cartilage of the concha cymba and cavum. Turbinate hypertrophy should be noted, and the nasal mucosa and vestibule should be examined for scaring or webbing. Webbing is a common source of postoperative nasal obstruction, often caused by scarring or failure to properly close endonasal incisions.

Next, a careful analysis is performed of the external and internal nasal valves. No decongestant is applied initially. The nasal valves are carefully examined without the use of a nasal speculum at first so as not to distort the natural anatomy. A speculum is then used to better evaluate the internal nasal valves. Still without decongestant, the patient is asked to grade his or her airflow through each side of his nose on a scale from 0 to 10. A cerumen curette is inserted into one side of the nose to gently support and lateralize the external and internal nasal valves. The patient is asked to grade the resultant airflow again from 0 to 10 while gently occluding the contralateral nostril. The location of support that gives maximal improvement is carefully recorded. The procedure is then repeated on the other side. After decongestant is applied, the entire evaluation is repeated again to weigh the effects of mucosal edema on obstruction. These maneuvers, when combined with a thorough examination, can accurately predict the area of maximal obstruction and can help guide the surgeon as to the best surgical treatment.2

Finally, the nose is examined endoscopically to exclude contributing pathology from the middle meatus or nasopharynx.

Specific Deformities of the Nose after Rhinoplasty

Specific Deformities of the Nose after Rhinoplasty

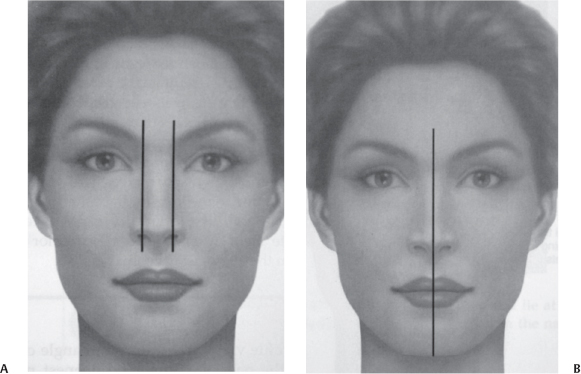

Upper Third

A successful rhinoplasty often will direct visual emphasis to a patient’s eyes in addition to enhancing the patient’s nose. Nasal bones too widely spaced may give the impression of telecanthus. Asymmetric shadows and bony irregularities of the nose may divert attention from the eyes. The bony width of the bony sidewall of the nose should be approximately 75% of the distance of a normal alar base on frontal view (Fig. 1–1). Deviations of the nose can be more readily appreciated by drawing a straight line from the midpoint between the brows to the upper lip and central incisors, provided there are no gross facial skeletal asymmetries (Fig. 1–1).

Two widths relate to the upper third of the nose: the nasal width and the facial width. The nasal width is the width created by each nasal bone as it traverses from the midline horizontally, before it curves toward the face. The facial width is the width created by the nasal bone and the nasal process of the maxilla as it traverses down to meet the horizontal face of the maxilla (Fig. 1–2).

Persistently wide nasal bones after previous rhinoplasty have several anatomic causes. The original surgeon may have performed either incomplete osteotomies (green stick fractures) or neglected to perform osteotomies all together. In patients with extremely wide nasal bones preoperatively, an intermediate osteotomy may have proven useful for further narrowing.3 Placement of the lateral osteotomy too far medially is likely to lead to palpable bony step offs.

Some patients have a persistently wide dorsum despite adequate lateral osteotomies. This may be caused by wide horizontal portions of the nasal bones, widening the nasal width without affecting the facial width of the nose. Excision of medial aspects of the nasal bones may be required to adequately reduce the nasal width in these patients (Fig. 1–3).

Overly narrowed nasal bones may result from osteotomies unnecessarily performed on an already narrow nose. A collapsed nasal bone can be the result of too aggressive a medialization of the nasal bone. Nasal bone instability also can be the result of overaggressive elevation or tearing of the overlying periosteum before osteotomies or violating the underlying mucoperichondrium using wide osteotomes.

Figure 1–1 (A) The ideal width of the upper one third of the nose is 75% of the distance of the alar base. (B) A midline drawn from the central glabella to central incisor may help better define any deviations of the nose (From Papel ID, Frodel J, Holt GR, Larrabee WF, et al. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Thieme; 2002. Reprinted by permission.)

A “rocker deformity” occurs when the osteotomy takes place too far cephalically, onto the nasal process of the frontal bone. When the nasal bone is medialized, the superior segment narrows, but the caudal segment moves out laterally, causing visible deformity and persistent widening. As a general rule, osteotomies should either take place below the level of the medial canthus to avoid this deformity or course medially before arriving at the nasal process of the frontal bone.

Bony height discrepancy also may lead to persistent asymmetry. Lee, Kang, Choi, et al described performing an intermediate osteotomy in select cases to compensate for severely asymmetric bony vaults.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree