Chapter 20 Alopecia

1. How is alopecia classified?

Alopecia (hair loss) can be divided into: 1) disorders of the hair shaft and 2) all other forms of hair loss. Abnormalities of the hair shaft can produce alopecia because the shafts are fragile and “break off.” The other forms of alopecia can be divided into cicatricial (scarring) and noncicatricial alopecia. In cicatricial alopecia, hair is lost permanently. Both cicatricial and noncicatricial alopecia can be divided into diffuse and patterned hair loss. In diffuse hair loss, hair thins evenly from all parts of the scalp, and discrete “bald spots” do not occur. In patterned alopecia, certain areas of the scalp are affected more than others.

3. Can cicatricial and noncicatricial alopecia be differentiated clinically?

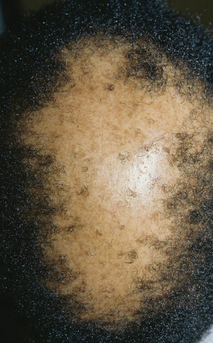

In the setting of alopecia, cicatricial means that there has been permanent destruction of hair follicles, and they have been replaced by fibrous tissue. Usually, an obvious scar, such as that seen after wounding, is not evident, but there is a loss of follicular openings that gives the scalp a smooth and shiny appearance (Fig. 20-1). The texture of the scalp may remain soft and supple, although sometimes induration or firmness is palpable.

4. What causes common balding?

People who become bald have hair follicles that are genetically programmed to miniaturize under the influence of postpubertal androgens. Probably, several genes (inherited from both mother and father) influence the severity of balding. Until very late in the balding process, the number of hairs does not decrease, but the hairs become progressively smaller until they are no longer visible to the naked eye. Except in very marked and long-standing balding, very fine, short hairs can be seen exiting from follicular orifices if a magnifying lens is used.

Randall VA: Androgens and hair growth, Dermatol Ther 21(5):314–328, 2008.

5. How effective are medical treatments for common balding?

About one third of balding patients who use topical minoxidil solution experience significant (cosmetically obvious) hair regrowth. Any regrowth that occurs is only maintained while the drug is used. If therapy is stopped, hair density reverts to its pretreatment state. Oral finasteride, a 5α-reductase inhibitor, is somewhat more effective, and can be used in combination with topical minoxidil.

6. Is common balding in women managed differently than in men?

Women whose balding is a manifestation of hyperandrogenism (excessive production of circulating androgens) may benefit from therapy directed at the cause of hyperandrogenism. Polycystic ovarian disease, late-on-set congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing’s syndrome, and adrenal and ovarian neoplasms are potential causes of hyperandrogenism. In the absence of elevated circulating androgens, nonspecific therapy directed at suppressing ovarian androgen production or blocking the peripheral effect of androgens is sometimes tried. Oral contraceptive agents (to suppress ovarian androgen production) and spironolactone are most often utilized for this purpose. Topical minoxidil solution is also useful, but oral finasteride is seldom used in women.

7. What are the surgical options for treatment of balding?

Men, and occasionally women, can achieve permanent cosmetic improvement by undergoing a hair transplantation procedure. Hair follicles from the occipital area (donor site) are moved to the balding area (recipient site). The procedure is tedious and expensive, but the cosmetic results can be quite good. Various other surgical procedures, including scalp reductions (which involve excising the bald areas) and scalp flaps, are sometimes used in selected patients.

8. Discuss the common causes of circular bald spots.

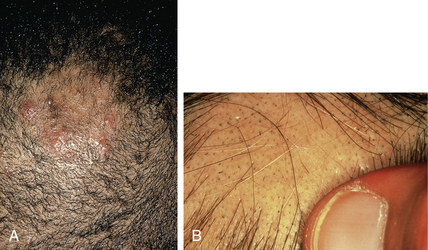

Although many forms of alopecia can result in a circular bald patch, the most common causes are tinea capitis and alopecia areata. Tinea capitis is a superficial fungal infection with a predilection for children, especially black children. The surface of the skin is scaly and sometimes inflamed, and small dark stubs of hair (“black dots”) may be scattered within the affected area. In this condition, the hair shaft is invaded and replaced by myriad circular fungal spores. In the United States, Trichophyton tonsurans is usually the culprit. A circular, scaly, or crusted bald spot on the scalp of a black child should be considered to be tinea capitis until proven otherwise (Fig. 20-2A).

Alopecia areata also commonly affects children, but adults more often develop the condition. In alopecia areata, the affected areas may be totally hairless, but the scalp surface looks otherwise normal, without scaling and minimal, if any, erythema. A few short hairs may be present in the bald spot; these “exclamation mark” hairs tend to taper and lose pigment as they approach the scalp and may appear to float on the surface of the scalp (Fig. 20-2B).