Class I occlusion

The mesiobuccal cusp of the first permanent maxillary molar occludes in the buccal groove of the permanent mandibular first molar

See Fig. 2.1

Class II malocclusion

The mesiobuccal cusp of the first permanent maxillary molar occludes mesial to the buccal groove of the permanent mandibular first molar

See Fig. 2.2

Class III malocclusion

The mesiobuccal cusp of the first permanent maxillary molar occludes distal to the buccal groove of the permanent mandibular first molar

See Fig. 2.3

Overjet

Overjet is a horizontal (anterior-posterior) distance, of the upper incisors ahead of the lower incisors. Normal overjet is between 1 and 3 mm

Negative overjet

Negative overjet or reverse overjet is where the upper incisors are behind the lower incisors

See Fig. 2.3

Overbite

Overbite is a vertical distance, the maxillary incisors overlap the mandibular incisors. Normal overbite is between 3 and 5 mm

Open bite or apertognathia

Overbite ≤0 mm. Is a type of malocclusion characterized by the occlusion of posterior teeth without anterior occlusion

See Fig. 2.5

Deep bite

Deep bite is an increase of the overbite (>5 mm)

See Fig. 2.7

Crossbite

Crossbite is an occlusal irregularity where a tooth (or teeth) has a more vestibular or lingual position than its corresponding antagonist tooth in the upper or lower arcade

See Fig. 2.5

The maxillary and mandibular dental midlines are assessed to determine whether they are congruent with each other and with the facial midline. Deviations are noted and quantified. The presence and degree of dental compensation is also recorded. Dental compensation is the tendency of teeth to tilt in a direction that minimizes the dental malocclusion. Compensation will camouflage the deformity and restore proper overjet and overlap. If orthodontic tooth movement cannot produce the necessary facial changes, then surgery should be indicated.

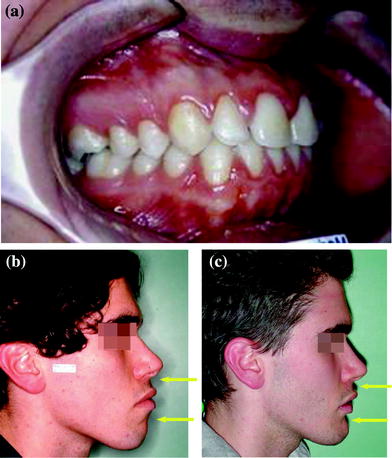

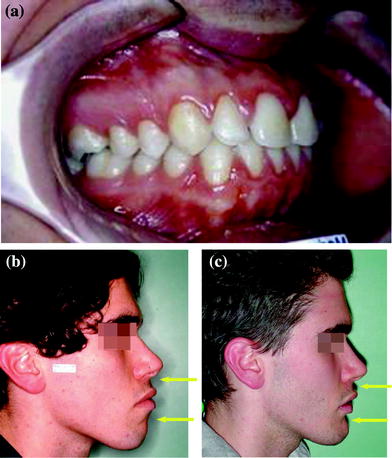

Fig. 2.1

Intraoral photograph of Class I occlusion (a). Despite normal interdental relationships, the aesthetical examination of the same patient (b) documents a jaws biprotrusion. The surgical correction consisted of superior and inferior dentoalveolar osteotomies. (c) Post-operative lateral view

Fig. 2.2

Class II malocclusion

Fig. 2.3

Class III malocclusion

2.2 What’s Beauty?

Clinical facial analysis [7] defines appearance, proportions, volumes, symmetry and visible deformities; it is a crucial phase of surgical planning that can visualize, evaluate and prioritize existing problems. But what determines beauty? The canons of beauty have changed over time. The harmony of shapes related to ‘gold number’ or ‘divine proportion’ to which artist were inspired in every period of history for their representations (Da Vinci, Vitruvio, Botticelli). Some features symbolize an idea or feeling and inspire emotions absolutely unique in the observer. ‘Regions of Interest’, or ‘facial points of interest’, theorized from Yarbus, are angles, maximal curvature points and unpredictable curve of the outline (curve that change in the different positions of vision): the lip commissure and the lateral and medial canthus are angular points of interest; the root of the nose and the labial-mental furrow are concavities and the tip of the nose, superior and inferior lip and chin are convexities. In the past, notions of beauty were envisaged as arbitrary cultural conventions with no uniformly accepted standard of what constitutes an attractive face. However, during the last decade, a greater understanding of the shared preferences for attractive faces has led researchers to regard certain aspects of facial attraction as inherent and definable, transcending social and cultural fashions. Some studies suggested that female face attractiveness is greater when the face is symmetrical, is close to the average, and has certain features (e.g. large eyes, prominent cheekbones, thick lips, thin eyebrows and small nose and chin) [8, 9]. Symmetry is a characteristic of attractive faces, but there are some exceptions to the rule. Under certain conditions, symmetry can be completely unattractive; the visual impact of symmetry on the perception of beauty increases significantly when approaching the midline [10]. The frontal facial view (Fig. 2.4) [11] provides information on the midlines, levels, outline and heights of the face. In particular, orbital rim, subpupil and alar base contours are noted. Vertical facial planning of facial or occlusal cants, midline deviations and general facial outline is determined by information gained from the clinical facial examination. The facial evaluation begins with assessment of these vertical facial thirds: trichion to glabella, glabella to subnasale, and subnasale to menton; each of these facial thirds should be about equal (Figs. 2.5, 2.6). The most important factor in assessing the vertical height of the maxilla is the degree of incisor showing while the patient’s lips are in repose. A man should show at least 2–3 mm, whereas as much as 4–5 mm is considered attractive in a woman. If the patient shows the correct degree of incisor in repose, but shows excessive gingival in full smile, the maxilla should not be impacted (Fig. 2.7). The intercanthal distance should be the same as the distance between the medial and lateral canthus of each eye. The inferior orbital rims, malar eminence, and piriform areas are evaluated for the degree of projection. If these regions appear deficient, maxillary advancement is indicated. The alar base width should also be assessed prior to surgery since Le Fort I osteotomy may alter the width. Asymmetries of the maxilla and mandible are documented on physical examination, and the degree of deviation from the facial midline is noted. The soft-tissue envelope of the upper face is evaluated for descent of the malar fat pads, the severity of the nasolabial creases and folds. These changes are associated with aging; however, skeletal movements of the maxilla will affect these areas. It is important for the surgeon to realize that skeletal expansion (anterior or inferior repositioning of the jaws) will improve the creases and folds, whereas skeletal contraction (posterior or superior movements of the jaws) will accentuate these aspects and appearance of premature aging. The surgeon can frequently take advantage of skeletal expansion to reduce some of these soft-tissue creases, giving the patient a youthful appearance and reducing the signs of aging (Fig. 2.8). In evaluating the chin, the clinician assesses the labiomental angle. An acute angle may indicate a short or prominent chin, and effacement of the crease typically excessive vertical length or insufficient anterior projection. The profile view is used to assess the projections of the face (Figs. 2.9, 2.10). Projections analysis is divided into high midface, maxillary and mandibular areas. An experienced clinician can usually determine whether the deformity is caused by the maxilla, the mandible, or both just by looking at the patient. This assessment is made clinically and verified radiographically with cephalometry. Holdaway describes a ‘harmony line’ or H line that extend from pogonion to the most prominent part of the upper lip. The line that runs from the soft-tissue nasion to the pogonion meets the H line to create the H angle. An average H angle is 10 degrees; a larger angle relates to increasing soft-tissue profile convexity. The proper position of the nose relates to the upper lip, which is supported by the maxillary incisors, and the chin. Because both of these structures may be altered by orthognathic surgery, it is important to predict how the dimensions of the nose will fit into the new facial proportions. The soft tissues of the neck are also assessed. The patient with submental laxity will not benefit aesthetically from posterior positioning of the mandible. Mandibular advancement, however, will improve the laxity and the cervicomental angle.

Fig. 2.4

Frontal facial analysis. The ideal face is vertically divided into equal thirds by horizontal lines adjacent to trichion, glabella, nasal base, and menton. The lower third is divided into two parts: the upper lip makes up the upper third, and the lower lip and chin compose the lower two-thirds