2 The acute shortage of deceased donors in the UK – recommendations set in an international context

Introduction

Although there has been a shortage of deceased donors for as long as organ transplantation has been part of established clinical practice, that shortage has never been more extreme – or been perceived to be so – than it is now. This is the result of a number of factors, of which perhaps the most important is the very success of transplantation. It would be facile to suggest that the problems of rejection have been overcome – but certainly acute, early rejection has almost disappeared as a cause of graft loss. Chronic graft loss, which may or may not be primarily immunological, remains a major issue but current immunosuppressive regimens are continuing to improve the long-term outcome for transplant recipients (primarily through early outcomes) and transplantation has also become safer. As a result more patients are surviving their first, failed transplant and are in need of a re-transplant. More importantly, the relative success and safety of transplantation means that far more patients are being considered suitable for transplantation – it is not that long ago that, for kidney transplantation, ‘older’ patients were those over the age of 60, and many centres were reluctant to list such patients. Similarly, patients with diabetes were thought to represent too high a risk in some centres.

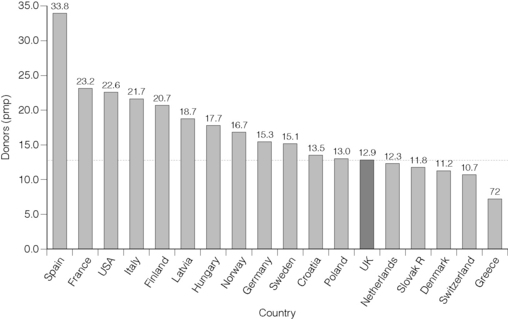

Fifteen years ago the deceased organ donor rate in the UK was broadly in line with that of most other western European countries. Sadly that is no longer the case and of those countries with well-developed organ donation and transplant services, we now sit uncomfortably close to the bottom of the league table (Fig. 2.1). Of our closer neighbours only Denmark and The Netherlands have a lower donor rate (expressed as donors per million population) and many have rates close to double that of the UK. The rate in Spain is now nearly three times higher.1

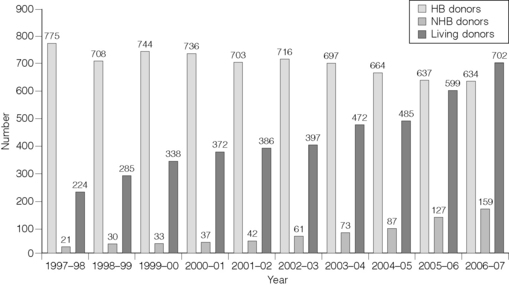

There have been considerable efforts in recent years to address this problem and in the case of donors after cardiac death (previously known as non-heart-beating donors) these efforts have met with considerable success. The number of such donors is still relatively small (approximately 20% of all deceased donors) but it has risen by 350% in the past 6 years. However, the number of donors after brain death (heart-beating donors) has fallen over the same time period by 14%, and such donors remain the bedrock of liver, heart and lung transplantation. In part to compensate for this lack of deceased donors, the number of living donor kidney transplants has increased markedly (Fig. 2.2) and now accounts for 33% of all kidney transplants. Nothing demonstrates the critical shortage of deceased donors more clearly than the willingness of donors, recipients and clinicians to put at risk the life of a fit healthy person in this way.

The need for transplantation

That there is a shortage of suitable organ donors is beyond dispute, but the true extent of the shortage in the UK is far less clearly established. The obvious starting point for any assessment of the need for transplantation would seem to be the number of patients waiting for a transplant – or, more specifically, the number of new patients added to the list each year. However, these figures give only a partial answer to the question because they reflect exactly what they say and – crucially – do not reflect the number of patients who may benefit from a transplant that are not added to the waiting list. There is some form of rationing of access to all forms of transplantation but the details differ from organ to organ.

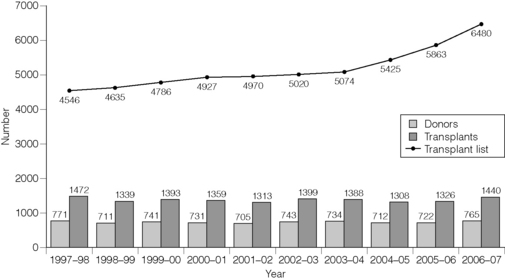

For many years in the UK the number of patients added to the kidney transplant list was relatively static at just over 2000 adults each year (and approximately 100 paediatric patients) but the number increased markedly between 2004 and 2006 and has now reached over 3300 per year. More patients aged over 40 are being registered and the increase is most marked in those over 60 years of age. The number of patients of Asian origin has doubled. As a result, the number of patients actively waiting for a kidney transplant is rising more rapidly than ever before (Fig. 2.3).

For the kidney transplant list there are published national assessment criteria modified from the European Best Practice Guidelines.2 The underlying principle is that patients should have an anticipated survival post-transplant of at least 2 years and this is combined with a series of clinical parameters. Some of these can be assessed accurately but inevitably many are a question of judgement and it is notable that – relatively recently – the proportion of dialysis patients aged under 65 years that were listed for a transplant varied across the UK from 23% to 67%.3

Clinical practice in liver and cardiothoracic transplant centres is more complex. For a patient with renal failure, listing for a transplant offers a possible escape, eventually, from dialysis and some patients are relatively content to dialyse for many years even though that hope is never realised. For patients with end-stage liver, heart or lung disease, however, there is no realistic alternative and many clinicians are reluctant to hold out the hope of a life-saving transplant to more patients than are realistically likely to be able to receive an organ. As a result, the number of patients listed for a liver transplant in the last financial year was 814, for a heart transplant was 194 and for lung transplantation was 204. Despite this practice, between 10% and 15% of these patients die before a transplant becomes available, or are removed from the list because their condition deteriorates beyond the point at which transplantation is appropriate.

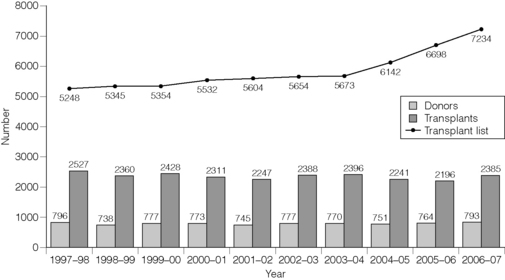

It is apparent from this that the waiting list at any given time is a very poor indication of the need for transplantation, representing as it does not only the balance between new patients listed and those removed from the list following a transplant or their death or deterioration, but also the inevitable rationing of access to a transplant list that is a consequence of the shortage of donors. However, the waiting list continues to rise, and the gap between ‘supply’ and ‘demand’ is rising (Fig. 2.4). For the record, the active UK transplant lists at 27 December 2007 were:

| Kidney | 6691 |

| Kidney/pancreas | 229 |

| Liver | 307 |

| Heart | 85 |

| Heart–lung | 20 |

| Lung | 258 |

| Other | 20 |

It should also be noted that the organ allocation system might have a direct impact on waiting list practice. For example, in the USA for many years a major part of the liver allocation algorithm was the time for which the patient had been listed. As a result clinicians would happily list patients with slowly progressive liver disease who were several years away from needing a liver transplant, in the hope that by the time the patient’s liver function had deteriorated the patient would have accumulated enough waiting time to be allocated an organ. At one time the USA (population 300 million) liver waiting list approached 15 000 patients – the highest year-end figure reached in the UK (population 60 million) is 360. The move to a Mayo End-stage Liver Disease (MELD)-based allocation system in the USA (i.e. primarily on the basis of clinical need) has seen the waiting list fall markedly.4

There is one further source of information that gives some indication of the need for transplants – the Council of Europe annual Transplant Newsletter.1 This provides international figures on organ donation and transplantation, although it is the donation figures that are most widely known. The transplant figures are revealing, although international comparisons can be fraught with difficulties. For each organ, Table 2.1 shows the transplant rate per million population (pmp) in 2006 in the UK and the range in five of the western European countries with the highest rates (Spain, France, Belgium, Norway and Sweden).

Table 2.1 Transplant rate per million population (pmp) in 2006 in the UK and the range in five western European countries*

| Organ | Transplant rate (pmp) | |

|---|---|---|

| UK | Europe | |

| Kidney | 23.2 | 25.7–46 |

| Liver | 10.7 | 13.2–23.5 |

| Heart | 2.6 | 4.4–7.4 |

| Lung | 2.0 | 3.3–8.4 |

* Spain, France, Belgium, Norway and Sweden.

Current obstacles to organ donation in the UK

Introduction

There are a number of ‘external’ factors that will undoubtedly have an impact on organ donation rates – although the extent of that impact is a matter of debate. The overwhelming majority of deceased donors after brain death are patients whose clinical care has been provided in critical care units, although there is a small but increasing number of such patients that are identified in Accident and Emergency departments. It is inescapable that the number of intensive care beds in a local region or country will influence clinical practice in the admission to ICU of patients with catastrophic brain injury and it is notable that Spain, with its donor rate that is three times greater than that of the UK, has many more critical care beds pro rata than the UK. Differences in the number of road traffic accident deaths and the incidence of intracerebral bleeding may also have an impact when making international comparisons, and when appropriate adjustments are made some of the international variation can perhaps be explained.5,6

There are also concerns about the definitions used in international comparisons.7 The donation rate can be expressed most meaningfully in terms of the number of potential donors that become actual donors – i.e. the ‘conversion rate’8 – and the number of potential donors is, at least in part, influenced by some of these ‘external’ factors.

However, what is essential in any donation system is to maximise the conversion rate, and there is clear evidence that the UK is not succeeding in this regard. The UK Transplant Potential Donor Audit (PDA) was established in April 20039 and, whilst it is acknowledged that the format of the PDA can be improved, it provides important information. The data for the past 2 years10 suggest that over 20% of patients in whom brainstem death was a possible diagnosis were not in fact tested, that only 81% of patients certified dead after brainstem tests were referred to the donor coordinator network, and that the consent rate when the potential donor’s family were approached was only 61%. The overall conversion rate was 48%. Even allowing for uncertainties about the PDA it is clear that at each stage of the process that can lead to organ donation there are patients who could potentially be donors after brain death who do not in fact become donors.

The Organ Donation Taskforce

There have been a number of previous reports into donation and transplantation in the UK, none of which has been implemented in full, and in addition to reviewing the available evidence the Taskforce commissioned further work on various aspects of donation. It took evidence from those most involved with the successful Spanish model, which has been introduced in northern Italy and several South American countries, and with the more recent Organ Donation Breakthrough Collaboratives in the USA. The final Taskforce Report was publicly launched in January 2008. As this Report is the most significant structured approach to improving donation in the UK for many years, much of the remainder of this chapter will be based largely on the approach taken by the Taskforce and on its recommendations, although the author takes sole responsibility for this description that in parts goes beyond the Report itself. The report is available at http://www.dh.gov.uk (http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_082122).

The key stages in organ donation

Donor identification

Both steps – brainstem testing or treatment withdrawal – must be made solely in the patient’s best interests and should be made regardless of whether organ donation is possible or not. This is a fundamentally important point. There would still appear to be too many situations where the use of brainstem tests to diagnose death are felt to be necessary only when organ donation is being considered and it is the clear view of the Taskforce – and of both the General Medical Council and the British Medical Association – that brainstem death testing should be carried out in all patients where brainstem death is a likely diagnosis even if organ donation is an unlikely outcome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree