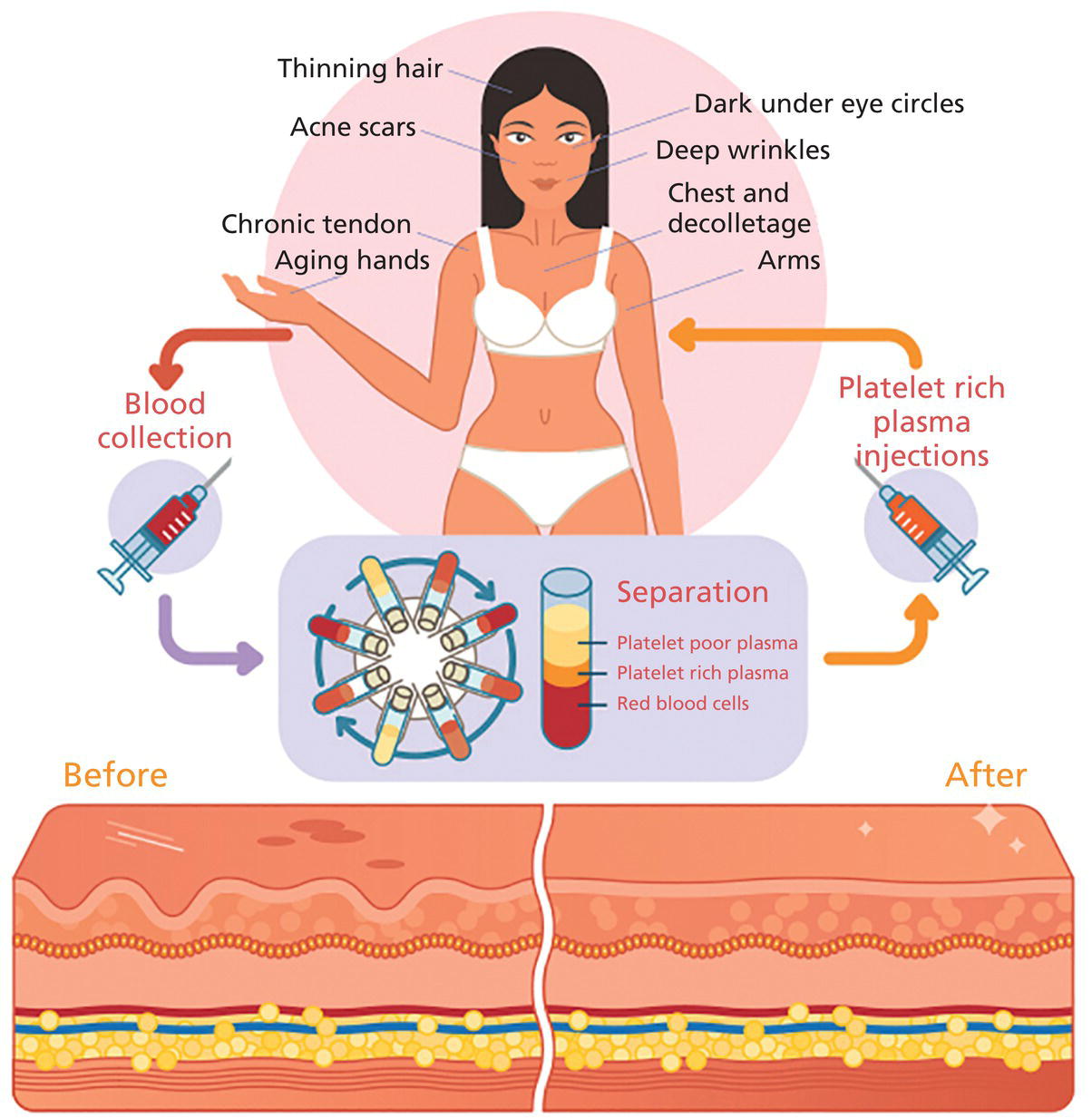

Lawrence A. Rheins, Shaun Wootten, and Lynn Begovac Department of Research and Development, Aesthetics Biomedical Inc, Phoenix, AZ, USA A discussion about the uses of platelet rich plasma (PRP) in cosmetic dermatology requires some initial review of basic platelet biology. Platelets, also known as thrombocytes, serve as the major cell responsible for blood coagulation regarding injury to the body [1, 2]. They are derived from a bone marrow precursor, megakaryocytes. Platelets have no cell nucleus; they are fragments of cytoplasm derived from the megakaryocytes [3]. An average human platelet blood count ranges between 150,000 and 350,000 platelets per/μL. The clinical definition for PRP is 1,000,000 (five to seven times baseline) platelets/μL. Platelets contain multiple unique organelles, the dense granules, lambda granules, and the alpha granules. The alpha granules contain, seven key growth factors, platelet‐derived growth factors (PDGFaa, PDGFbb, PDGFab), transforming growth factors (TGF‐b1, TGF‐b2), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and epithelial growth factor (EGF) [2, 4]. The dense granules contain ADP or ATP, calcium, and serotonin, molecules for mitochondrial metabolism. The lambda granule contents are involved in resorption during repair. Recent reports suggest that the platelets may contain over 1000 growth factors/biomolecules [5]. Within the platelet, when vascular injury occurs, platelets are recruited by the body to the injury site. The platelets attached to injured epithelium (thru adhesion). The cells will typically change shape and begin to release biochemical messengers (activation). Finally, the platelets connect to other platelets through receptor bridges (aggregation) [2]. This platelet plug (primary hemostasis) begins the full coagulation cascade leading to fibrin deposition. This cascade with other circulating proteins leads to tissue repair in the body [2]. The origins for the clinical use of PRP goes back to the 1970s, where hematologists were looking for treatments for patients with various platelet deficiency disorders (e.g. thrombocytopenia) [6]. Fifteen years later the field of Orthopedic Medicine took a leadership role with PRP treatments [7]. Osteoarthritis, tendon strains, rotator cuff tears, large joint degeneration (hip, shoulder, knee) are common maladies for a sport‐oriented yet active aging society. PRP infusion into damaged orthopedic joints has become a more routine, safer approach for healing tissue [8]. Clinical evidence demonstrates that PRP joint treatments have resulted into stronger, more mobile joint repair, and resulting in speedier recovery times. PRP can stimulate new cartilage growth in the joints, areas typically with poor vascularity [9]. Thoracic surgeons have been routinely using PRP following sternal surgery to accelerate healing, keep infection mitigated at this critical surgical site. Typically, during extensive cardiac procedures patients will need multiple transfusions. PRP used during these treatments can significantly reduce the amount of homologous blood the patient requires, reducing the overall surgical risk [10]. Back/spinal problems are one of the most common chronic conditions in the United States. Early joint problems over time can lead to painful disc degeneration and loss of mobility [11]. Back specialists are using PRP to slow down the degeneration process, healing the tissues, and reducing spinal fluid leakage [11]. It’s been reported that PRP can help regrow damaged bone tissue [12]. Dentistry, maxillofacial surgery, and wound clinics routinely use patient PRP as part of patient’s overall treatment plan [13–20]. With the growing use of PRP in cosmetic dermatology and other medical subspecialties, a paramount question remains, what are the FDA Guidelines, and oversight for using PRP. Currently, the PRP is not regulated and there remains no formal approved use for PRP. When using PRP therapy, it’s the preparation, use of specific centrifuges, and PRP collection kits that do fall under the FDA’s 510K Clearance Guidelines (Pre‐Manufacture Notification) for medical devices [21–23]. The correct centrifuge products and uses are critical to ensure reliable and reproducible PRP volume (Figure 55.1) [24] including platelet numbers. Manufacturers can receive clearance to use these products. Specific PRP preparation processes fall under the purview of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) [25]. This FDA division has responsibility for overseeing human tissues and cells, including the biological products these tissues produce. (FDA’s 21 CFR 1271 of the Code of Regulations Outlines the Processing and Usage of the Human Tissue Products [26]. (PRP is exempt from this code).) Figure 55.1 Preparation of PRP clip art. The correct preparation of PRP is critical to ensure reliable and reproducible volume of PRP and adequate platelet numbers. Centrifuges and PRP collection kits are regulated by FDA as 501K medical devices. Source: From [24]. Physicians and other licensed medical professionals will often conduct “off‐label” uses for PRP therapy. However, the FDA does request physicians to be well versed in the clinical science, PRP preparation, and exact use of PRP for the therapeutic indication. In addition, a full accounting of the patient’s health status prior to utilizing PRP therapy is a requirement, along with monitoring and reporting any serious adverse events. The PRP preparation is a Point of Care (in Physician/Health Care Professional) office environment. The FDA operates under a risk‐based and science‐based approach as it develops regulations for supporting innovative regenerative medicine products/devices. Presently, PRP can routinely be used for aesthetic procedures following the current FDA guidelines with approved centrifuges and collection kits. To appreciate the widespread interest and growing use of PRP more clearly in cosmetic dermatology, one needs to review the celebrity aspect for the genesis of PRP for aesthetic treatments. The origin of the Vampire treatment began in the early 2000s by the German Orthopedic Surgeon, Dr. Barbra Sturm [27]. Dr. Sturm focused early on the use of PRP for joint and severe osteoarthritic, and other inflammatory conditions. Dr. Strum believed low grade chronic inflammation contributes to the overall aging process. In 2013, she treated the late Kobe Bryant for his tendon injury, the “Kobe Procedure” [27]. The field of orthopedic medicine provided a new focus on the aging process. Those learnings by Dr. Sturm were then further transformed into an aesthetic application. PRP could be obtained by a blood draw, centrifugation, followed by microneedling and final application of the PRP [27]. Dr. Sturm’s PRP cream consists of well‐defined skin care ingredients, hyaluronic acid, vitamins, amino acids, and proteins. During this time celebrity endorsements for dermatology cosmetic procedures were just being recognized. However, it was not until the reality star Kim Kardashian (2013) had her PRP treatment televised that clearly piqued the public’s interest about the “Vampire” treatment. The plastic surgery and cosmetic dermatology communities were intrigued by the approach, with several physicians routinely offering to their aesthetic patients. Since those beginnings with facial PRP, Charles Runels MD has taken the Vampire treatment to a more comprehensive approach, inventing the Vampire Facelift Procedure ® . Additional clinical inventions by Dr Runels’ include enhanced facial and genital rejuvenation procedures. However, the paucity of reported controlled studies along with the lack of peer reviewed publications, has made it difficult for many aesthetic care professionals to clearly understand the reported clinical efficacy associated with these reported PRP treatments. PRP continues to gain traction for other cosmetic dermatologic indications. Two particular areas of clinical focus are hair restoration for androgenic alopecia and aging facial rejuvenation [28–37]. PRP for hair growth works by stimulating hair follicles through the PDGF release and stimulation of the follicular stem cells. The process prolongs the proliferative anagen phase for the hair follicles as well as promoting perifollicular vascularization helping to preserve survival of the dermal papilla fibroblasts [36]. Both male and female pattern hair loss as well as alopecia can be improved with PRP injections. Results have been promising, although several studies due to study design, specific criteria for patient selection have presented less then superior results. Frequency, dosing, and maintenance to ensure continued clinical benefit with follow‐on treatment are still being investigated. Studies using injectable PRP into facial skin has demonstrated increases in collagen density, elastic fibrils with associated reduction of fine lines/wrinkles, improvement of skin texture and tone [38–42]. Further, PRP used with other treatments such as laser, microneedling RF, and fillers have demonstrated enhanced cosmetic outcomes [43–50]. Other studies have demonstrated a decrease in erythema and edema in acne and traumatic scars. A drawback to current PRP administration is the pain associated with scalp and facial injections, often requiring significant anesthesia for patient comfort and to help ensure that the provider has the best treatment outcome. The early 1990s ushered in the science of tissue engineering. Early pioneer companies, e.g. Advanced Tissue Sciences Inc. and Organogenesis Inc. developed the process to manufacture full three‐dimensional skin constructs. These products were used to treat diabetic foot ulcers and burns, as well as alternatives to animal testing. The initial source for manufacturing these products were neonatal foreskin cells. What the scientists learned was that the cell culture medium that the foreskin cells were growing had a plethora of growth factors, amino acids, peptides.

CHAPTER 55

The Growing Role for Platelet Rich Plasma in Cosmetic Dermatology

Introduction

Clinical history of platelet rich plasma (PRP)

The role of the FDA and PRP

Advent of the “Vampire” aesthetic treatment

Cosmetic dermatology and PRP

Autologous growth factors, the ultimate personalized cosmetic product

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree