Procedure 51 Volar Plate Arthroplasty for Dorsal Fracture-Dislocations of the Proximal Interphalangeal Joint

Indications

Inability to achieve and maintain a perfect/concentric reduction of an acute/subacute fracture-dislocation of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint is seen.

Inability to achieve and maintain a perfect/concentric reduction of an acute/subacute fracture-dislocation of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint is seen.

Inability to maintain reduction is often due to fracture of a significant volar articular portion of the middle phalanx with comminution that prevents open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF).

Inability to maintain reduction is often due to fracture of a significant volar articular portion of the middle phalanx with comminution that prevents open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF).

Deitch and colleagues (1999) have shown that dislocations in the absence of fracture, or when less than 30% of the volar articular surface of the middle phalanx is fractured, usually allow a stable concentric reduction of the joint. When 30% to 50% of the volar articular surface of the middle phalanx is involved, a stable concentric reduction is less likely, and when more than 50% of the articular surface is fractured, a stable concentric reduction is unlikely to be achieved with closed means alone.

Deitch and colleagues (1999) have shown that dislocations in the absence of fracture, or when less than 30% of the volar articular surface of the middle phalanx is fractured, usually allow a stable concentric reduction of the joint. When 30% to 50% of the volar articular surface of the middle phalanx is involved, a stable concentric reduction is less likely, and when more than 50% of the articular surface is fractured, a stable concentric reduction is unlikely to be achieved with closed means alone.

Examination/Imaging

Clinical Examination

Acutely, the patient will present with pain to the PIP joint of the affected digit and a clinically obvious deformity and swelling in the digit.

Acutely, the patient will present with pain to the PIP joint of the affected digit and a clinically obvious deformity and swelling in the digit.

Alternatively, the patient may present after initial reduction of the dislocation, and the clinical findings may be relatively benign with some mild swelling and pain in the affected PIP joint. If this is the case, it is critical to scrutinize a true lateral radiograph to rule out persistent subluxation because the patient may no longer have clinically evident malalignment. Failure to correct persistent subluxation will result in a poor outcome.

Alternatively, the patient may present after initial reduction of the dislocation, and the clinical findings may be relatively benign with some mild swelling and pain in the affected PIP joint. If this is the case, it is critical to scrutinize a true lateral radiograph to rule out persistent subluxation because the patient may no longer have clinically evident malalignment. Failure to correct persistent subluxation will result in a poor outcome.

Imaging

Films of the digit, including a true lateral radiograph of the affected digit centered on the PIP joint, are required. Persistent subluxation can be recognized when the articular surface of the middle phalanx projects dorsal to a line drawn along the dorsal cortex of the proximal phalanx. Additionally, the joint space should be symmetrical both volarly and dorsally (Fig. 51-1).

Films of the digit, including a true lateral radiograph of the affected digit centered on the PIP joint, are required. Persistent subluxation can be recognized when the articular surface of the middle phalanx projects dorsal to a line drawn along the dorsal cortex of the proximal phalanx. Additionally, the joint space should be symmetrical both volarly and dorsally (Fig. 51-1).

Surgical Anatomy

The PIP is a hinge joint with a 100- to 110-degree arc of motion. Its stability is derived from both the bony architecture of the joint and the surrounding ligamentous structures.

The PIP is a hinge joint with a 100- to 110-degree arc of motion. Its stability is derived from both the bony architecture of the joint and the surrounding ligamentous structures.

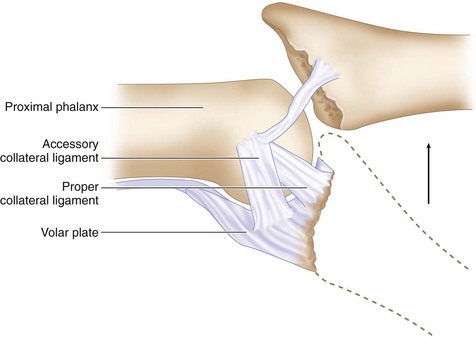

The collateral ligaments are the primary restraints to radial or ulnar joint deviation. They are 2 to 3 mm thick and originate on the lateral aspect of each condyle of the proximal phalanx, passing obliquely and volarly to insert on the volar third of the base of the middle phalanx and the volar plate.

The collateral ligaments are the primary restraints to radial or ulnar joint deviation. They are 2 to 3 mm thick and originate on the lateral aspect of each condyle of the proximal phalanx, passing obliquely and volarly to insert on the volar third of the base of the middle phalanx and the volar plate.

The volar plate forms the floor of the joint and resists hyperextension of the PIP joint. It originates from the periosteum of the proximal phalanx and the lateral thick, cordlike checkrein ligaments. It inserts across the volar base of the middle phalanx and is confluent with the collateral ligament insertions laterally.

The volar plate forms the floor of the joint and resists hyperextension of the PIP joint. It originates from the periosteum of the proximal phalanx and the lateral thick, cordlike checkrein ligaments. It inserts across the volar base of the middle phalanx and is confluent with the collateral ligament insertions laterally.

Because the collateral ligament–volar plate complex inserts on the volar third of the middle phalanx, fractures that involve more than 30% to 40% of the volar articular segment are inherently unstable after reduction. This happens because these ligamentous restraints are attached to the fracture fragment and not to the remaining middle phalanx, which then tends to sublux dorsally. Additionally, a fracture fragment of this size also compromises the inherent bony stability by detaching the volar buttress of the articular surface that cups the proximal phalangeal condyles (Fig. 51-2).

Because the collateral ligament–volar plate complex inserts on the volar third of the middle phalanx, fractures that involve more than 30% to 40% of the volar articular segment are inherently unstable after reduction. This happens because these ligamentous restraints are attached to the fracture fragment and not to the remaining middle phalanx, which then tends to sublux dorsally. Additionally, a fracture fragment of this size also compromises the inherent bony stability by detaching the volar buttress of the articular surface that cups the proximal phalangeal condyles (Fig. 51-2).

Exposures

A standard Bruner incision centered at the PIP flexion crease is used to expose the joint (Fig. 51-3).

A standard Bruner incision centered at the PIP flexion crease is used to expose the joint (Fig. 51-3).

Dissection is carried down bluntly, and the radial and ulnar neurovascular bundles are identified and mobilized (Fig. 51-4).

Dissection is carried down bluntly, and the radial and ulnar neurovascular bundles are identified and mobilized (Fig. 51-4).

The flexor sheath is incised between the A2 and A4 pulleys as a rectangular flap to enable later repair.

The flexor sheath is incised between the A2 and A4 pulleys as a rectangular flap to enable later repair.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree