Primary Cutaneous CD30+ Lymphoproliferative Disorders

Lymphomatoid papulosis and cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma are included in the group of the “CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders” in the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues [1]. These entities represent two ends of a spectrum without clear-cut boundaries, and “borderline” cases may be difficult to classify precisely as either lymphomatoid papulosis or cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. In the WHO classification it is stated that “From a clinical perspective lymphomatoid papulosis is not considered a malignant disorder, despite demonstration of monoclonality in many cases” [1]. In my opinion, lymphomatoid papulosis is indeed malignant, albeit low-grade, and progression to more aggressive lymphoma types is observed only in a small percentage of patients.

The CD30 antigen is a cytokine receptor belonging to the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily. The antigen was initially described within Reed–Sternberg and Hodgkin cells of Hodgkin lymphoma, and subsequently identified within neoplastic cells of a new group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas (anaplastic large cell lymphoma). Soon after the first description, it become clear that anaplastic large cell lymphoma could occur as a primary skin tumor, where it was characterized by a good prognosis [2]. The term “cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders” has been subsequently proposed to denote a group of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas characterized by expression of the CD30 antigen and favorable prognosis, including lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma [3, 4]. Cases described in the past as “regressing atypical histiocytosis” or “pseudo-Hodgkin disease” are part of the spectrum of primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders [5]. In addition, most, if not all, cases reported as “primary cutaneous Hodgkin lymphoma” represent in my view examples of either lymphomatoid papulosis or cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (see Chapter 24 and Teaching case 24.1).

It should be underlined that CD30 is a very important marker for diagnosis and classification of cutaneous lymphomas, but interpretation of the staining cannot be made without knowledge of full phenotypic features and complete clinical information. I have observed cases of aggressive cytotoxic lymphomas or even B-cell lymphomas (not to mention the many pseudolymphomas) that had been erroneously classified as cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma because of CD30 positivity. These mistakes can have disastrous consequences for patients. Several similar cases with incomplete phenotypic features and possibly erroneous diagnoses have been published in the literature. In this context, it must be clearly underlined that a diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis or cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma should be made only upon compelling evidence, particularly in cases that present with clinical features that are not typical of these disorders.

Several studies attempted to elucidate the reason(s) for the frequent partial or complete spontaneous resolution of the lesions and the good prognosis of cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders. It has been suggested that CD30 and CD30-ligand are involved in the control of apoptosis and that activation of the CD30 signaling pathway plays a role in tumor regression [6]. Resistance to CD30-mediated growth inhibition provides a possible mechanism for escape from tumor regression in cases with more aggressive behavior. A higher expression of apoptotic-related proteins has been observed in lymphomatoid papulosis as compared to cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, suggesting that the apoptosis index may play a role in the spontaneous resolution of the lesions and better prognosis of lymphomatoid papulosis [7].

As already mentioned, there is no clear-cut boundary between lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. The term “borderline lymphomatoid papulosis – anaplastic large cell lymphoma” has been used by some authors for cases where a definitive diagnosis is not possible. In this group are included cases with clinical aspects of lymphomatoid papulosis and histopathologic features of primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma and vice versa (see the section on borderline cases in this chapter).

Several studies investigated the relationship and differential features of lymphomatoid papulosis and cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Recent data revealed that IRF4 gene rearrangements are found in both conditions, although more commonly in cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma [8–10]. Increased expression of the Toll-like receptors (TLRs) 2, 4, 7, and 9 has been detected in the keratinocytes overlying infiltrates of lymphomatoid papulosis type C as well as of cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma [11]. Higher numbers of forkhead box protein P3 (FOX-P3)+ T-regulatory (Treg) lymphocytes were observed in lymphomatoid papulosis as compared to cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, suggesting that these components of the reactive infiltrate may play a role in the better prognosis of patients with lymphomatoid papulosis [12]. The inhibitor of differentiation 2 (Id2, located on 2p25) and the oncogenic transcription factor Fra2 (located on 2p23) are aberrantly expressed both in anaplastic large cell lymphoma and in lymphomatoid papulosis [13]. Deregulation of the ID2 and FRA2 genes may be involved in the reorganization of chromosome 2 prior to the t(2;5) translocation. This genetic feature may represent an important step also for cases of translocation-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma [13], possibly representing a common molecular background of both anaplastic large cell lymphomas and lymphomatoid papulosis. In this context, the level of Fra2 and Id2 is lower in lymphomatoid papulosis than in anaplastic large cell lymphoma, suggesting that gene dosage may be involved in progression and invasiveness of these diseases [13].

Lymphomatoid Papulosis

Lymphomatoid papulosis is defined as a chronic, recurrent, self-healing eruption of papules and small nodules with the histopathologic features of a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (“rhythmic paradoxical eruption”) [14].

The etiology of the disease is unknown. Some cases of lymphomatoid papulosis present an IRF4 translocation [8–10]. The interchromosomal (2;5) translocation is absent [15, 16]. No repeatable association with inflammatory skin disorders or viral infections have been demonstrated.

In 10–20% of patients lymphomatoid papulosis is preceded, concomitant with, or followed by another type of lymphoma (usually mycosis fungoides, Hodgkin lymphoma, or anaplastic large cell lymphoma, but other malignant hematologic disorders have also been observed) (see also Chapter 2) [17–20]. The percentage was higher (40%) in one study [21], possibly due to referral bias. A second lymphoma has been observed in a similar proportion of patients also in children with lymphomatoid papulosis [22]. In some of the patients with lymphomatoid papulosis and associated lymphomas, the same clone of neoplastic T lymphocytes has been identified in lesions of the two lymphoproliferative disorders, raising the question of a possible common origin of the diseases [23–25]. However, response to treatment is different, and lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis may continue to appear while the second lymphoma is in complete remission [26]. In two patients with lymphomatoid papulosis associated with a B-cell malignancy, exacerbation of lymphomatoid papulosis was observed during therapy with rituximab, suggesting that the B lymphocytes may play a role in the control of the disease [27].

In patients with mycosis fungoides, self-healing papules with CD30+ lymphoid infiltrates may develop during the course of the disease, possibly suggesting a diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis associated with mycosis fungoides. In these patients it is of crucial importance to rule out a large cell transformation of mycosis fungoides. In fact, one case that our group published in 1991 as “PUVA-induced lymphomatoid papulosis in a patient with mycosis fungoides” [28] died with large cell transformation of mycosis fungoides 48 months after the onset of the “lymphomatoid papulosis” (see also Chapter 2). As a matter of fact, differentiation of mycosis fungoides with CD30+ large cell transformation from lymphomatoid papulosis or cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma is extremely difficult and may be impossible in given cases. Useful information may be obtained by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for IRF4 translocations. Most cases of mycosis fungoides with CD30+ large cell transformation are negative for IRF4 translocations, whereas cutaneous large cell anaplastic lymphoma is constantly positive [8, 10]. The FISH analysis is of less value for discrimination of mycosis fungoides-associated lymphomatoid papulosis, however, as only a minority of cases of lymphomatoid papulosis are positive [10].

In addition to these hematologic malignancies, patients with lymphomatoid papulosis are also at higher risk of developing non-lymphoid second malignancies [29].

In the absence of specific symptoms of other associated diseases, complete staging investigations are not necessary in patients with lymphomatoid papulosis. As well as in some healthy individuals, T-cell clonality may be detected within the peripheral blood or the bone marrow of patients with lymphomatoid papulosis or cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, but the clones are not related to those of the cutaneous disorder and do not have clinical significance [30].

Clinical Features

Young adults are usually affected, but lymphomatoid papulosis has been reported in children and in the elderly as well [31–37]. The hallmark of the disease, and a pre-requisite for the diagnosis, is the spontaneous resolution of the lesions, which is observed within a few weeks or, rarely, months. The time interval between two episodes is variable: some patients may experience several eruptions within short periods of time, whereas others may have only a few lesions over several years.

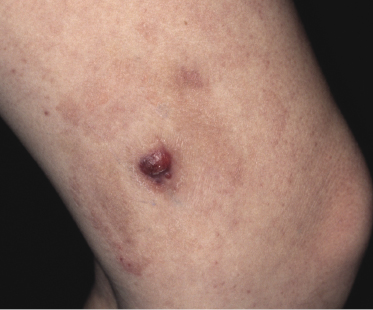

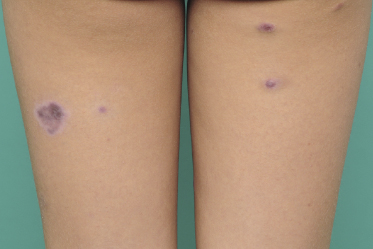

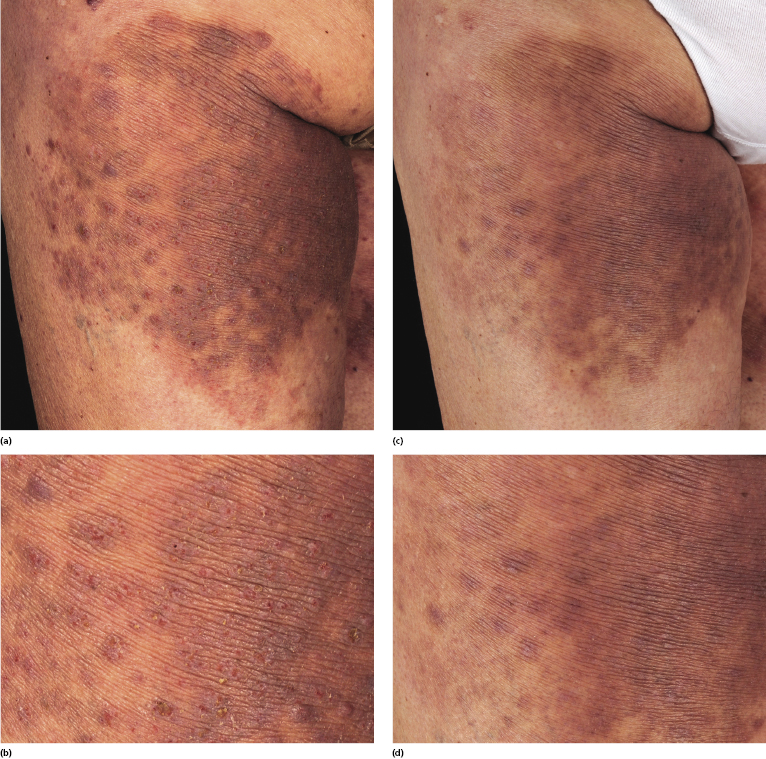

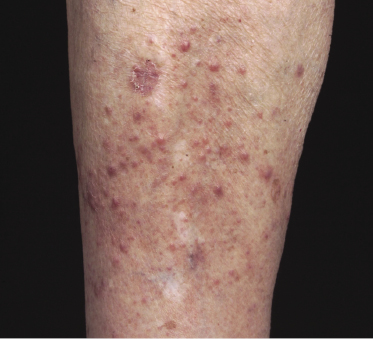

Clinically, lymphomatoid papulosis presents in most patients with a generalized eruption of reddish-brown papules or small nodules on the trunk and proximal extremities, but in some cases only a few lesions may be present (Figs 4.1 and 4.2). Oral or other mucosal involvement may be observed rarely, as well as involvement of the palms and soles (Figs 4.3 and 4.4). The size of the lesions is variable but they are usually smaller than 1 cm. In a few patients large, rapidly growing nodules, sometimes with ulceration, may be the first manifestation of lymphomatoid papulosis (Fig. 4.5) [3]. The onset of large tumors with complete spontaneous resolution has also been observed during the course of the disease (Fig. 4.6). In these cases the prognosis is not affected, suggesting that large tumors that regress spontaneously represent a morphologic variation of lymphomatoid papulosis rather than a transformation into a more aggressive lymphoma [3]. The clinical picture is usually polymorphic, due to the presence of lesions in different stages of evolution (Fig. 4.7). Ulceration is common, and sometimes is followed by prominent scarring (Fig. 4.8).

I have observed only in children a peculiar clinical presentation with perilesional depigmentation surrounding livid, flat resolving plaques, usually in the context of more conventional papules and small nodules of the disease (Fig. 4.9). Another uncommon presentation, seen both in children and adults, is related to angiodestruction and shows clinically deep red or livid hemorrhagic lesions that may be misinterpreted as a vasculitic process (Fig. 4.10). Sometimes small papules may be clustered with a herpetiform arrangement (Fig. 4.11) or tiny clustered papules may convey the impression of a large, flat plaque that deviates from the conventional clinical presentation (Fig. 4.12). In some patients, continuous recurrences of clustered lesions on a given body area are associated with post-lesional hyperpigmentation. Such lesions may be misinterpreted as large, infiltrated plaques and may suggest a clinical diagnosis of mycosis fungoides, but careful clinical examination and follow-up data allow them to be classified properly (Fig. 4.13). Another unusual clinical variant of lymphomatoid papulosis resembles clinical hydroa vacciniforme [38].

The onset of lymphomatoid papulosis has been observed after allogeneic stem cell transplantation, during pregnancy, and in patients with severe hypereosinophilic syndrome [39–41].

Regional Lymphomatoid Papulosis

In some patients, lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis are localized to just one area of the body (regional lymphomatoid papulosis) (Fig. 4.14) [42–44]. Such cases have been reported also as “persistent agmination” of lymphomatoid papulosis [43, 45]. A peculiar type of regional lymphomatoid papulosis was localized to the skin site of a Becker nevus [46].

Differentiation of regional lymphomatoid papulosis from cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma can be extremely difficult, because this last can present with nodules surrounded by satellite lesions of smaller dimensions, clinically similar to those observed in lymphomatoid papulosis. Analysis of IRF4 translocations by FISH may be helpful in such cases: cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma is commonly positive, as opposed to the rare positivity observed in lymphomatoid papulosis [10].

Histopathology, Immunophenotype, and Molecular Genetics

Histopathology

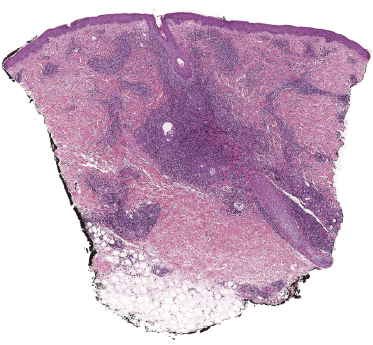

The histopathologic features of lymphomatoid papulosis are variable. Five main histologic subtypes (types A, B, C, D, and E) and several other variants have been described. It is important to recognize that these variants can all be observed in one patient at the same time or during the course of the disease, and that the histopathologic picture does not have any prognostic implication (see Teaching case 4.1). Sometimes, features of different histological subtypes may be found even in a single lesion.

Type A (“Conventional” Type)

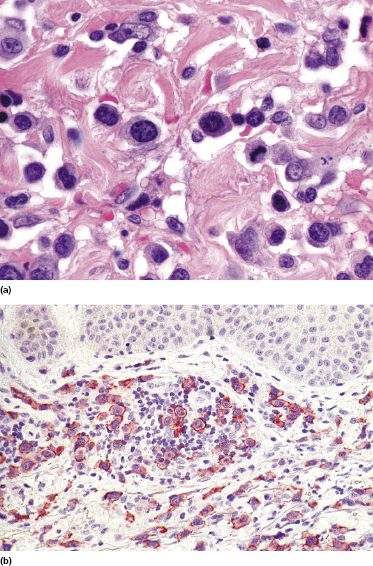

This is the most frequent histopathologic type of lymphomatoid papulosis, characterized by wedge-shaped lesions with the presence of scattered or clustered large, atypical, anaplastic cells admixed with small lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils (Figs 4.15 and 4.16). In past publications it was referred to as the “histiocytic” type because the large, atypical cells bear some morphologic resemblance to histiocytes (and were believed to be of histiocytic origin as well). Epidermotropism is variable. Necrosis may be present and is related to the age of the lesion. Scattered intraepidermal necrotic keratinocytes may be observed as well, but are an uncommon finding. Large, atypical lymphocytes resembling Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells are found in some of the cases.

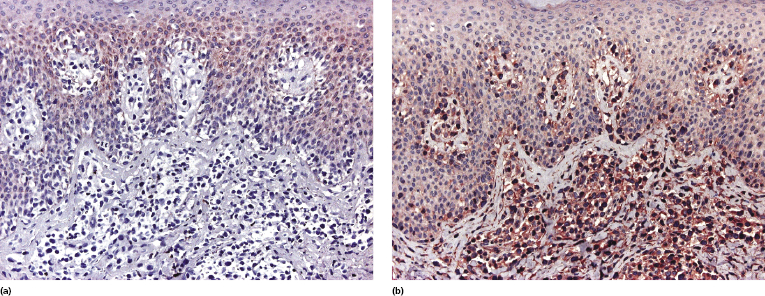

Type B (Mycosis Fungoides-Like)

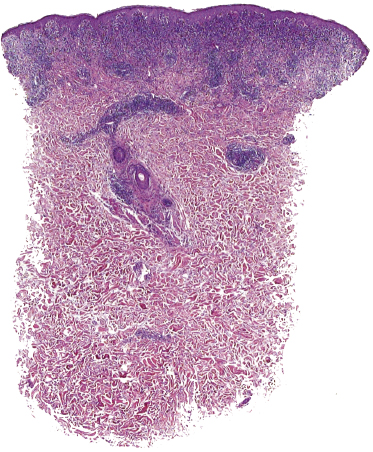

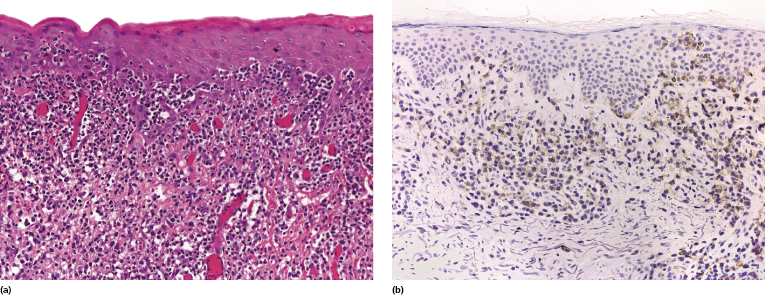

This is a rare type of lymphomatoid papulosis that reveals a wedge-shaped or, more rarely, band-like infiltrate of CD4+, small- to medium-sized pleomorphic cells with epidermotropism (Fig. 4.17). Small intraepidermal collections resembling Darier’s nests (Pautrier’s microabscesses) may be observed (Fig. 4.18a) and can be highlighted with a staining for CD30 (Fig. 4.18b). Some large cells are usually found within the dermal infiltrate. It is crucial to understand that differentiation of lymphomatoid papulosis type B from mycosis fungoides can be achieved only by clinicopathologic correlation and that a diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis type B should never be established without a complete clinical history. While epidermotropism is a characteristic feature of both type B and type D lymphomatoid papulosis (and, parenthetically, can be observed in variable degrees in all other types as well), neoplastic cells in type D are strongly positive for CD8 and the epidermotropism is more pronounced, simulating the picture of cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma.

Although large atypical cells are the hallmark of lymphomatoid papulosis and the existence of a “small cell” variant may seem a morphologic contradiction, lymphomatoid papulosis type B may be conceptually compared to the small/medium cell variant of anaplastic large cell lymphoma, which is a well-recognized morphologic subtype of that lymphoma.

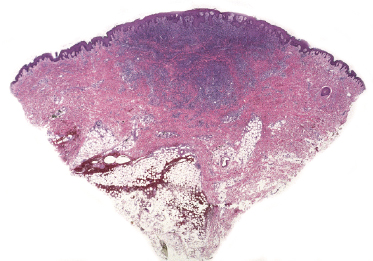

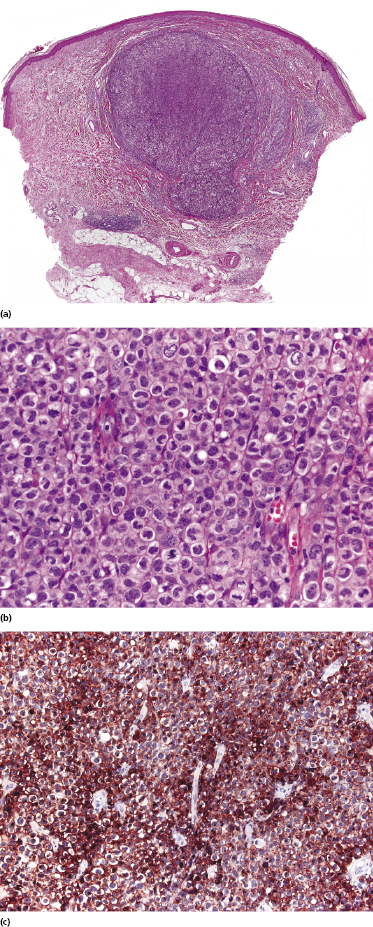

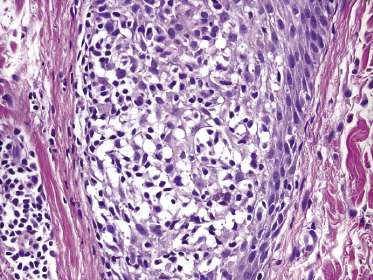

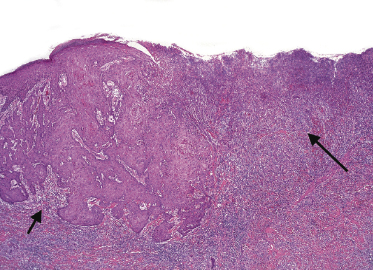

Type C (Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma-Like)

Lymphomatoid papulosis type C is characterized by a nodular infiltrate with sheets of cohesive, large atypical cells admixed with a few small lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils (Fig. 4.19). The histopathologic features are indistinguishable from those of cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, and a definitive diagnosis can be achieved only upon clinicopathologic correlation.

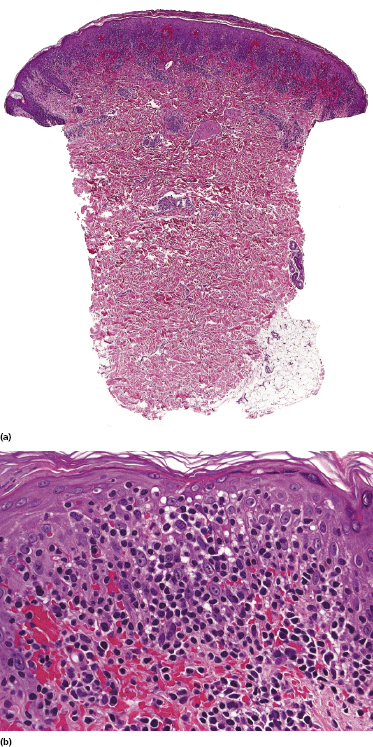

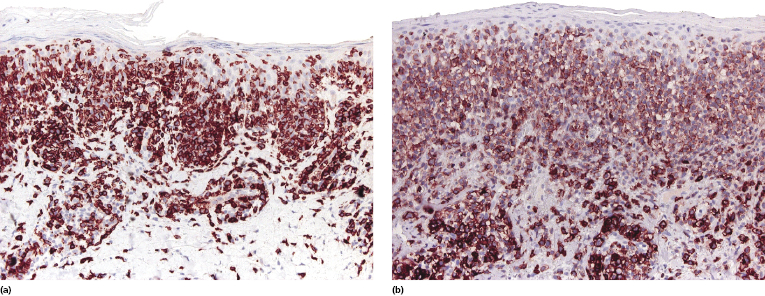

Type D (Cutaneous Aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ Cytotoxic T-cell Lymphoma-Like)

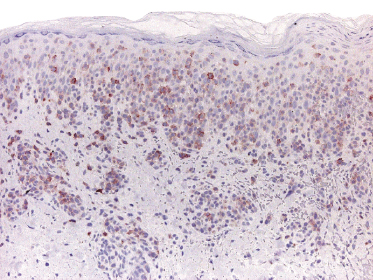

Our group described a variant of lymphomatoid papulosis characterized by marked epidermotropism of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes, simulating histopathologically the features of cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma [47]. Similar cases have been subsequently reported [48, 49]. The lymphoid infiltrate is either superficial and band-like, or wedge-shaped (Fig. 4.20a). Epidermotropism is prominent (Fig. 4.20b). In some cases, the combination of marked epidermotropism and hyperplastic epidermis convey an overall similarity to pagetoid reticulosis. Neoplastic lymphocytes strongly express CD8 (Fig. 4.21a). Demonstration of CD30 positivity is a prerequisite for the diagnosis (Fig. 4.21b). It must be underlined, though, that CD30 expression may be weak in some cases (Fig. 4.22). I have seen biopsies with negative staining in one laboratory and positivity on repeated staining in our laboratory. As in these cases evaluation of CD30 is paramount for diagnosis, care should be taken to get reliable results. In this context, external controls (i.e., staining of reference sections such as tonsil or other lymphoid tissues) do not provide any meaningful information, as the level of the antigen may be low in tumor cells but high in positive controls. In suspect cases we routinely perform two CD30 stainings with different protocols on separate, different automatic immunostainers.

The clinical features in all of these patients are typical of lymphomatoid papulosis. Follow-up data do not reveal any differences from other variants of lymphomatoid papulosis.

Type E (Angiocentric/Angiodestructive)

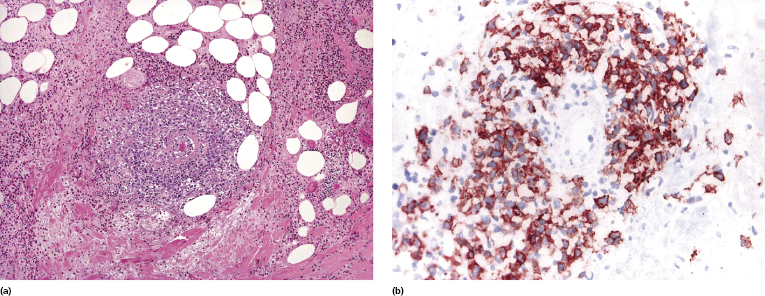

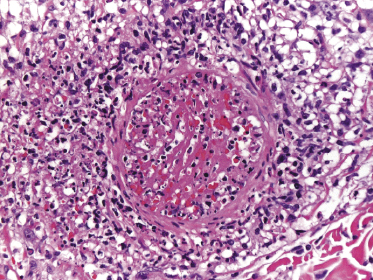

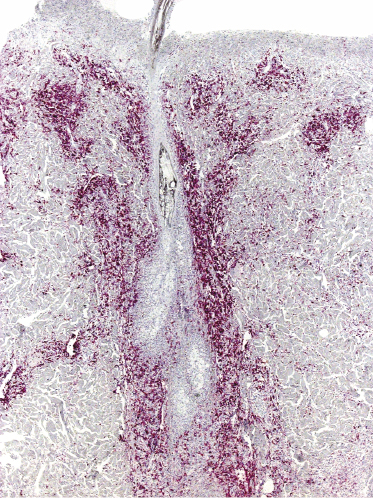

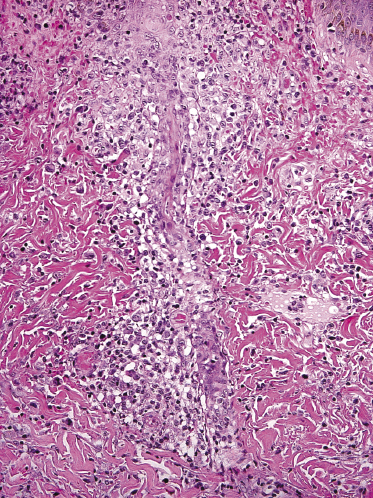

In some cases of lymphomatoid papulosis, prominent angiotropism with angiodestruction can be observed (Fig. 4.23a). The term “angioinvasive” lymphomatoid papulosis has been proposed for this variant [50]. CD30 and sometimes CD56 are expressed by the neoplastic cells (Fig. 4.23b). Some of the affected vessels may show intraluminal thrombi (Fig. 4.24).

The histopathologic presentation of lymphomatoid papulosis type E may mimic that of aggressive cytotoxic lymphomas, thus representing a pitfall in the diagnosis. In situ hybridization for EBV is constantly negative, allowing extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal-type, to be ruled out. Clinically, these cases are usually necrotic and often characterized by hemorrhagic lesions that may be misinterpreted as necrotizing vasculitis (see Fig. 4.10 and Teaching Case 4.1).

It should be underlined that focal angiotropism/angiodestruction may be rarely observed in other types of lymphomatoid papulosis as well. As for all variants of the disease, classification of a given lesion into a specific category may be subjective.

Follicular Lymphomatoid Papulosis (“Type F”)

A variant of lymphomatoid papulosis characterized by infiltrates located around a hair follicle has been termed “follicular lymphomatoid papulosis” (since types A to E have been described, this variant may be denominated “type F” for “follicular,” but the term is not widely accepted) [51–54]. Lesions are centered around the hair follicles, and these may be partially destructed by the infiltrate (Fig. 4.25). A diagnosis of follicular lymphomatoid papulosis should be made only when pilotropism is found besides a perifollicular infiltrate (Fig. 4.26). Staining for CD30 in these cases highlights the perifollicular distribution of the infiltrate and confirms the presence of positive cells within the hair follicle (Fig. 4.27).

It may be that at least some of the cases reported as follicular lymphomatoid papulosis represented conventional variants of the disease (type A) and that involvement of the hair follicle is not due to a particular pilotropism of tumor cells (this is especially true for cases arising in areas of the body with high numbers of hair follicles). On the other hand, true pilotropism is present in genuine cases, and in rare instances mucin deposition can be observed within the hair follicles as well, thus suggesting analogies with follicular (pilotropic) mycosis fungoides [54].

Other Histologic Variants

Other unusual histopathologic findings in lymphomatoid papulosis include the presence of myxoid changes, subepidermal blisters, and syringotropic/eccrinotropic or neurotropic infiltrates (Fig. 4.28) [30, 55, 56].

In some cases of lymphomatoid papulosis (and of anaplastic large cell lymphoma as well), a pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis can be observed [57, 58]. The association with multiple keratoacanthomas has been documented in a few cases [59]. I have rarely observed patients with multiple lesions that were in part conventional papules of lymphomatoid papulosis, in part conventional keratoacanthomas devoid of CD30+ cells, and in part typical “collision tumors” of lymphomatoid papulosis and keratoacanthoma (Fig. 4.29).

Immunophenotype

The hallmark of lymphomatoid papulosis is the expression of CD30 by neoplastic cells. The different patterns of CD30 expression in various types of lymphomatoid papulosis are depicted in Figs 4.16b, 4.18b, 4.19c, 4.21b, 4.22, 4.23b, and 4.27. CD30+ lymphocytes are arranged as solitary units between the collagen bundles or in small perivascular clusters. Sheets of CD30+ cells are observed only in the histopathologic type C. In some cases, most CD30+ cells are in the superficial part of the lesion, immediately below the epidermis. When epidermotropic neoplastic lymphocytes are present, they are invariably positive for CD30. The arrangement of CD30+ cells is useful in the differential diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis from benign inflammatory skin diseases where CD30+ cells are usually (but not always!) scattered and isolated. Another useful differential diagnostic criterion is the ratio between positive and negative cells, which is higher in lymphomatoid papulosis than in reactive inflammatory disorders (the ratio, however, may vary depending on the age of the lesion).

Although the infiltrate of type B lymphomatoid papulosis in the past has often been reported as being CD30−, all cases do in fact express the antigen, and a diagnosis should not be made by CD30-negativity [31]. Negativity in old reports was probably due to low levels of intracellular CD30 and at the same time lack of antigen demasking techniques, and it may have similar backgrounds as the weak positivity observed in some cases of the type D of the disease. In this context, care should be taken to avoid misinterpreting the papular variant of mycosis fungoides (which is always CD30−) as type B lymphomatoid papulosis (see also Chapter 2).

Neoplastic cells express the phenotypic markers of T-helper lymphocytes (CD3+, CD4+) in some cases and of T cytotoxic cells (CD3+, CD8+, TIA–1+) in others [31, 60, 61]. CD4+ cases may express cytotoxic proteins as well [61]. In lymphomatoid papulosis type D neoplastic cells are usually positive for CD45Ra, providing a useful clue for differentiation from cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma [62]. Expression of CD56 can be observed only rarely [31, 63–65]. Pan-T-cell antigens may be partially lost, but the pronounced aberrations observed often in cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma are not found in lymphomatoid papulosis.

Most lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis are characterized by a T-cell receptor (TCR) α/β phenotype, but expression of γ/δ can be observed in some cases (Fig. 4.30) [66].

The anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) is not expressed by neoplastic cells [16]. Positivity for JunB and c-Jun is found frequently in lymphomatoid papulosis [67, 68], whereas expression of fascin, survivin, and Bcl-2 is present in a minority of cases only [69, 70]. It has been suggested that CD56 or fascin expression by neoplastic cells may be helpful in the distinction between lymphomatoid papulosis and anaplastic large cell lymphoma [69], but in my experience the usefulness of these markers is very limited and they do not play any role in the differential diagnosis between the two diseases.

TRAF1 and MUM-1 are expressed in the vast majority of cases of lymphomatoid papulosis. In contrast to previous reports, stainings for MUM-1 and TRAF1 do not provide any helpful information in the differentiation of lymphomatoid papulosis from anaplastic large cell lymphoma [71, 72].

Molecular Genetics

Rearrangement of the T-cell receptor (TCR) is found in the majority of lesions [73], but some authors pointed to a less frequent presence of clonality in pediatric patients [74]. Studies on single cells after microdissection of the specimens showed that the atypical CD30+ large cells have a common clonal origin [75].

IRF4 gene rearrangements are found commonly in cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, but only in rare cases of lymphomatoid papulosis in the same studies [8, 10]. However, a recent publication showed that chromosomal rearrangement of the DUSP22–IRF4 locus on 6p25.3 is observed in a subset of cases of lymphomatoid papulosis with peculiar histopathologic features, characterized by epidermotropism and the presence of large dermal nodules of atypical cells [9].

Clinicopathologic Differential Diagnosis

Besides cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, the differential diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis includes other cutaneous papulonecrotic eruptions, and particularly pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) (see also Teaching case 4.2). The distinction between the two diseases can be particularly difficult, as they share overlapping clinicopathologic features. However, in the proper clinical background the presence of large atypical CD30+ cells is diagnostic of lymphomatoid papulosis. Cases reported as “pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis with atypical CD30+ cells” [76, 77] most likely represent examples of lymphomatoid papulosis. A report on CD30+ PLEVA associated with parvovirus B19 infection has been published [78]. However, many of the cases had phenotypic aberrations such as loss of pan-T-cell markers and/or double CD4/CD8 positivity, features that are very unusual in genuine PLEVA. On the other hand, a relationship between PLEVA and lymphomatoid papulosis, or the existence of transition forms, cannot be excluded a priori, and rare examples of lymphomatoid papulosis followed by pityriasis lichenoides have been reported [79].

Clusterin expression, originally thought to be specific for systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma as opposed to cutaneous cases, was found in half of tested examples of lymphomatoid papulosis in a study, as well as in tumor cells of cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma and in CD30+ large cell transformation of mycosis fungoides, but only in a small minority of cases of reactive infiltrates with CD30+ cells, thus representing a potential tool in differential diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis from CD30+ pseudolymphomas [80]. As with all other small studies, however, these results should not be overemphasized unless confirmed on larger numbers of cases.

Treatment

Since the disease is self-limiting, many patients with lymphomatoid papulosis will not require specific treatment [3]. Therapy should be directed mainly at controlling symptoms in widespread eruptions or slowing down the frequency of recurrences [3]. There are no data to support the efficacy of any given treatment scheme in diminishing the number and frequency of recurrences, and cutaneous relapses after discontinuation of any type of treatment are the rule. Even more important, there is no therapy that has demonstrated a preventive effect on the development of a second lymphoma.

Local steroids may be used in many cases, particularly when lesions are a few and/or localized. Psoralen + UV-A (PUVA) and low-dose methotrexate are the treatments that have been used more often in patients with generalized lesions [3, 81]. Methotrexate has also been administered topically. A further possibility is represented by bexarotene, either systemically or topically.

Many other options have been tested with partial success, including systemic steroids, UV-A1, interferon–α2a, interferon–γ, and retinoids (alone or in combination) [3, 81]. Some patients have been treated with imiquimod cream or 308 nm excimer laser. Only anecdotal cases have been managed with the anti-CD30 antibody (brentuximab).

Multiagent chemotherapy should be avoided, as it does not provide any protection from recurrences and/or progression to higher-grade lymphoma, and it may be associated with severe short-term and long-term side-effects. Radiotherapy has been advocated for the treatment of large tumors that may be slower to regress. However, all lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis eventually resolve, and local aggressive treatment such as radiotherapy should be administered only if the clinical setting is appropriate (e.g., large plantar lesions that may render walking impossible, or disfiguring lesions, etc.).

Finally, it should be mentioned that the analysis of data on different treatment modalities in lymphomatoid papulosis is hindered by the fact that lesions resolve spontaneously by definition. Usually a “shorter” time to resolution and/or a decrease of the frequency of the eruptions are considered significant in judging the value of a given treatment. However, resolution time is variable in the absence of any therapy and it may be very subjective to establish whether a given lesion has resolved earlier because of treatment, or not. In addition, the number of eruptions that a single patient experiences is also variable. A consensus statement of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)–Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force, the International Society of Cutaneous Lymphoma (ISCL), and the United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium (USCLC) defined complete remission as disappearance of 100% of the lesions and partial remission as a 50–99% clearance of skin disease from baseline without new larger (>2 cm in diameter) and persistent nodules (persistency being defined as no spontaneous regression after 12 weeks) in those with papular disease only [81].

Prognosis

Lymphomatoid papulosis is characterized by an excellent prognosis and the expected 5-year survival is 100% [1, 31, 32, 82]. Some patients may experience very few recurrences of the disease over the years, whereas others may have lesions appearing almost continuously. There are no features that can help predicting the course of the disease in a given patient. The presence of a monoclonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangement or of different histopathologic subtypes in the same patient have been suggested as prognostic indicators of possible progression to other lymphomas [83]. In my experience, however, these features do not allow to identify patients with different disease behavior.

It is still unclear whether long-standing, complete remissions may be achieved in lymphomatoid papulosis. In one study, 9/21 patients were in complete remission after a follow-up time variable between 1 and 18 years (median 6 years) [84]. However, the authors did not specify whether the patients experienced long-standing remissions or were just symptom-free at the time of the last follow-up control. In my experience, genuine lymphomatoid papulosis may show long periods of clinical remission, but recurrences are the rule rather than the exception.

As already discussed, the occurrence of large CD30+ tumors limited to the skin at onset of lymphomatoid papulosis or during the course of the disease does not affect the prognosis of these patients [3]. Large tumors may take longer to regress but do invariably so; on the other hand, patients with large lesions should be carefully monitored in order to rule out progression to a higher-grade lymphoma. Absence of any sign of regression after a period of 12 weeks should be regarded as suspicious, and the possibility of evolution into a second lymphoma should be seriously taken into account.

The knowledge that 10–20% of the patients develop an associated malignant lymphoma means that regular follow-up is required for these patients. Unfortunately, clinicopathologic, phenotypic, or molecular features do not provide clues for the early identification of patients who will progress to a more aggressive lymphoma. In addition, as already mentioned, there are no data to support a preventive effect of any given treatment on the progression or transformation of lymphomatoid papulosis into high-grade lymphoma.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree