Chapter 4 Anatomy for Augmentation: Cadaver and Surgical

Essentials of surgical anatomy are included in Chapters 11,12, and 13 that address inframammary, axillary, and periareolar incision approaches in detail. This chapter details principles of anatomy that apply to all incision approaches. Unembalmed (fresh) cadaver dissections are invaluable for surgeons to investigate details of surgical anatomy by performing surgical procedures and then dissecting the respective surgical fields with wide exposure to define specific tissue trauma that may occur with each approach. This approach to an in-depth understanding of what actually occurs as the result of specific surgical maneuvers is essential to help surgeons base their impressions on factual information instead of subjective opinions.

Anatomic Tissue Layers of the Breast and Chest

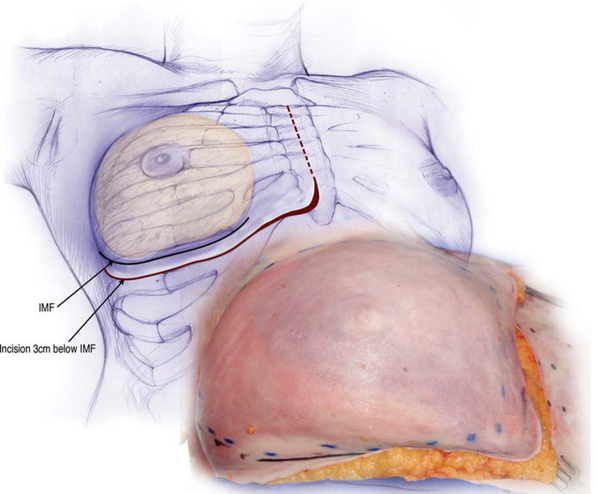

Figure 4-1 is the right breast in a fresh cadaver dissection. For wide exposure of the underlying tissue planes, an incision along the midline of the sternum connects with an incision that parallels the inframammary fold approximately 3 cm below the inframammary fold.

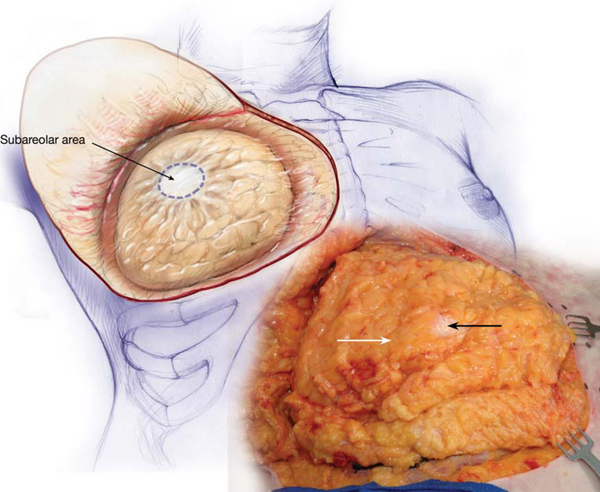

Dissection in the plane just deep to the deep subcutaneous fascia over the breast exposes the breast parenchymal mass (Figure 4-2) which consists of fatty infiltration of breast tissues with a whiter, fibroglandular tissue connection in the subareolar area. This tissue plane is largely irrelevant in primary breast augmentation unless the surgeon is combining a significant mastopexy procedure with the breast augmentation. When elevating skin flaps off underlying breast tissue, the plane of dissection is critical. Many surgeons, concerned about preserving vascularity to the skin flaps, dissect too deeply, leaving breast parenchyma attached to the skin flaps, when the ideal plane of dissection is immediately deep to the deep subcutaneous fascia. In the correct plane, skin flap elevation preserves optimal suprafascial (to the deep subcutaneous fascia) arterial supply and venous drainage, while minimizing a parenchymal burden deep to the flap that “steals” blood supply from the flaps. Conversely, dissecting excessively superficially when elevating skin flaps compromises critical arterial supply and even more critical venous drainage from skin flaps. The optimal plane of dissection for skin flap elevation, immediately deep to the deep subcutaneous fascia, is well known to surgeons who have performed a large number of mastectomies and to plastic surgeons who must work with the results of these dissections when performing breast reconstruction.

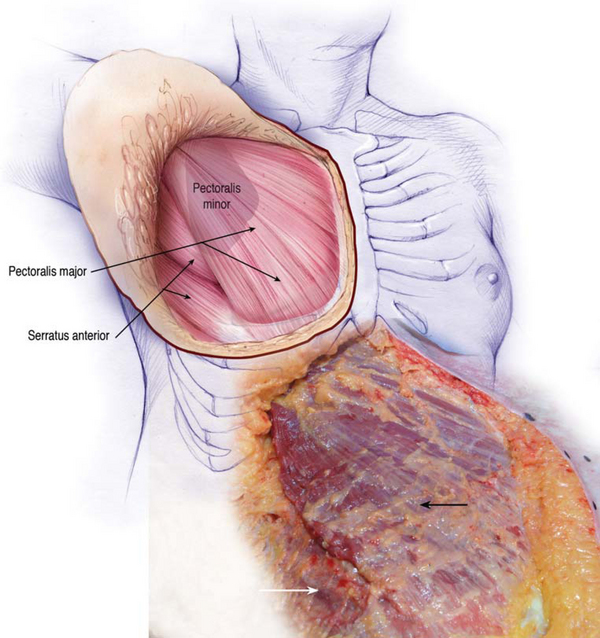

Reflecting the entire skin, subcutaneous tissue, and breast parenchyma superolaterally exposes the anterior surface of the pectoralis major muscle and the serratus muscle inferolaterally (Figure 4-3). During this dissection, a major objective was to leave pectoralis fascia attached to the anterior surface of the pectoralis major muscle in order to examine the thickness of this fascia in various areas beneath the breast. As a result, remnants of breast parenchyma and fat remain on the anterior surface of the pectoralis major muscle.

The serratus anterior muscle is located inferolateral to the pectoralis major muscle (Figure 4-3). While some surgeons claim to place implants completely beneath muscle using blunt, blind dissection techniques, elevating the serratus anterior muscle and preserving robust vascularity is challenging under direct vision with wide exposure, and is impossible using blunt, blind dissection techniques. Total muscle coverage, elevating serratus anterior and approximating it to the lateral border of the pectoralis, predictably blunts the inferior and lateral inframammary folds, and is unnecessary and undesirable in primary breast augmentation. The serratus muscle, overlying a breast implant, often suffers vascular compromise and fibrous infiltration over time. The serratus muscle provides unpredictable soft tissue coverage laterally, and often atrophies and blunts delicate lateral and inferolateral breast contours.

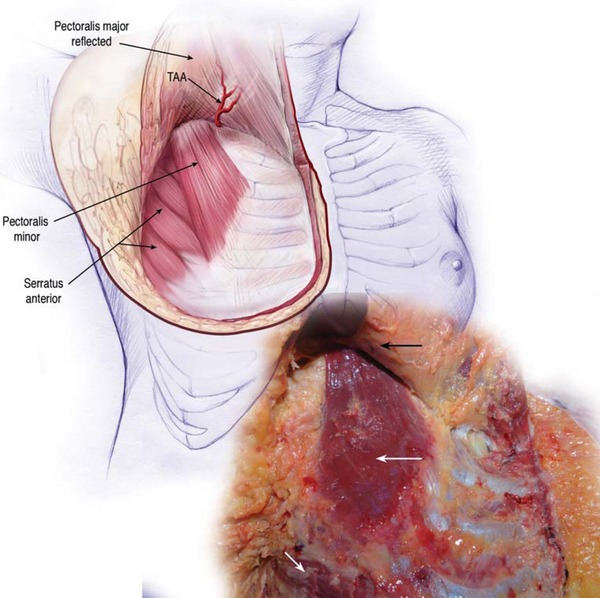

Reflecting the pectoralis major muscle superiorly (Figure 4-4) exposes the thoracoacromial pedicle on the deep surface of the pectoralis major muscle, and the pectoralis minor muscle and serratus anterior muscle attached to the chest wall deep to the pectoralis major muscle.

Critical Structures in the Subpectoral Tissue Plane

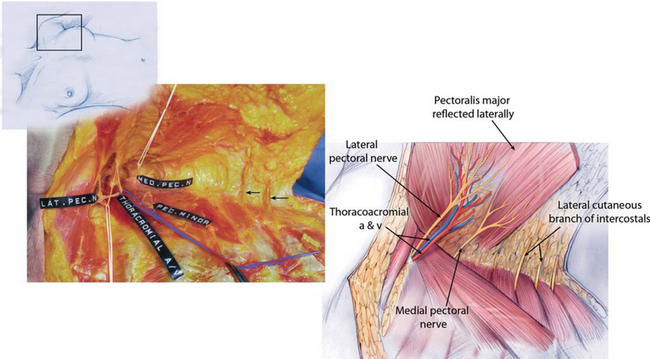

In another fresh cadaver specimen (Figure 4-5), viewing from medially over the sternum, the pectoralis major muscle is reflected laterally to expose structures deep to the pectoralis major. The lateral pectoral nerve courses with the thoracoacromial artery and vein through a fat pad deep to the pectoralis major and into the pectoralis major. The medial pectoral nerve in this specimen exits from deep to the pectoralis minor muscle at its superolateral border and courses anteriorly to innervate the lateral oblique portion of the pectoralis major muscle.

The location of the medial pectoral nerve can vary, with the nerve sometimes penetrating the pectoralis minor instead of exiting at the lateral border of the muscle. Clinically, the size of this nerve varies considerably. In most cases, surgeons can preserve this nerve when dissecting a subpectoral pocket, but occasionally the nerve exits through the pectoralis minor more inferiorly and can restrict optimal soft tissue redraping over an implant. Division of the medial pectoral nerve, while not optimal, does not produce clinically significant weakness of the pectoralis that causes symptoms in most patients. Laterally, anterior intercostal nerve branches (black arrows) exit the intercostal spaces and course anteriorly to innervate the breast.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree