Cutaneous Lymphoblastic Lymphomas

Lymphoblastic lymphomas are precursor hematologic neoplasms with aggressive behavior and relatively frequent skin involvement [1]. In spite of extensive staging investigations, the skin may appear as the only involved site in some patients, particularly in the B-cell variant of the disease [2–13]. These cases resemble conceptually so-called “aleukemic” leukemia cutis or primary cutaneous blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, where apparent exclusive skin involvement is invariably followed by overt leukemic manifestations, usually in a matter of a few months.

The distinction between leukemic and lymphomatous forms depends on the involvement of the peripheral blood and bone marrow, and is sometimes arbitrary. Although lymphoblastic lymphomas are divided into B and T types, rarely neoplastic cells do not express B- or T-cell markers, thus having a so-called “null-cell” phenotype. Distinction of these cases from other precursor neoplasms (e.g., natural killer (NK), myeloid) is extremely difficult, as some degree of overlapping phenotypic features may be observed. In fact, in the 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues a category of myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms with abnormalities in PDGFRA, PDGFRB, and FGFR1 genes has been introduced. These genetic aberrations are associated with multilineage differentiation, and cases of concomitant lymphoblastic lymphoma and myelogenous leukemia sharing this genetic background have been reported (see also Teaching case 20.1).

Although in general histologic features alone do not allow one to differentiate lymphoblastic lymphomas of B phenotype from those of T-cell lineage, in skin lesions a starry sky pattern is more common in the B-cell type of the disease and neoplastic cells in the T-cell type display a more pleomorphic morphology.

A trisomy of chromosome 4 was found in three cases of primary cutaneous lymphoblastic lymphoma (two of B-cell and one of T-cell type) [3].

Cutaneous B-Lymphoblastic Lymphoma

B-lymphoblastic lymphoma is a malignant proliferation of precursor B lymphocytes [1]. Cutaneous involvement is not rare but exact data are not available. Although patients usually have secondary skin manifestations of acute lymphoblastic leukemia with bone marrow and peripheral blood involvement, primary skin involvement has been observed occasionally [2–12].

Clinical Features

Children and young adults are usually affected, but cases in neonates have been also observed [2–16]. Clinically patients present with large erythematous tumors, usually solitary, commonly located on the head and neck (Fig. 23.1). In patients with precursor B-lymphoblastic leukemia, cutaneous involvement may be the first sign of recurrence after successful first-line treatment. In these cases skin manifestations may be characterized by solitary or localized papules and tumors that may be difficult to recognize (Fig. 23.2).

Histopathology, Immunophenotype, and Molecular Genetics

Histopathology

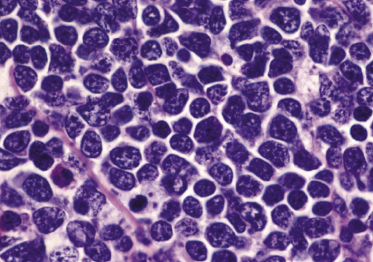

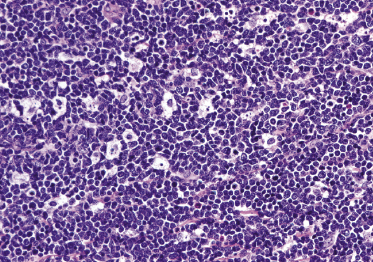

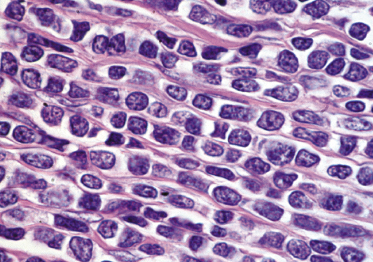

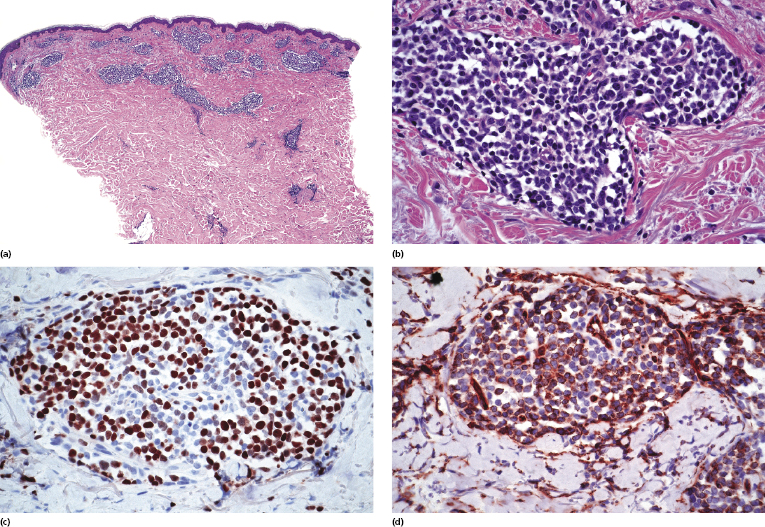

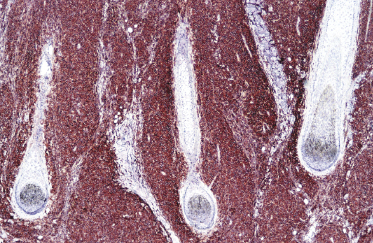

Dense, diffuse monomorphous infiltrates are found within the dermis and the subcutaneous fat. Cytomorphologically the lymphoblasts are medium-sized cells with round, oval or convoluted nuclei, fine chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm (Fig. 23.3). Mitoses and necrotic (“apoptotic”) cells are frequent, and “starry sky” or “mosaic stone”-like patterns may be seen (Figs 23.4 and 23.5). In secondary skin involvement from B-lymphoblastic leukemia, the pattern at low power may mimic that of an inflammatory skin condition, emphasizing the need for careful histologic and immunohistochemical examination to make a confident diagnosis (Fig. 23.6a and b).

Immunophenotype

Cutaneous B-lymphoblastic lymphoma expresses usually CD79a, TdT, CD10 (common acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma antigen – CALLA), paired box gene (PAX)-5, and cytoplasmic μ heavy chain without surface immunoglobulins (Figs 23.6c and 23.7). CD20 is positive in the majority of cases. A proportion of cases are also positive for CD99 and CD34 (Fig. 23.6d). Expression of the various markers is related to the stage of differentiation of the cells and B-cell markers may be negative in some cases.

Molecular Genetics

Molecular genetics shows a monoclonal rearrangement of the immunoglobulin (Ig) genes in virtually all cases. Although a polyclonal pattern of the T-cell receptor (TCR) genes is more commonly found, in a variable proportion of cases a concomitant monoclonal rearrangement of TCR and Ig genes can be observed, giving rise to potential pitfalls in the molecular diagnosis of the tumor.

Several genetic aberrations have been described in B-lymphoblastic lymphoma, resulting in the identification of specific variants listed in the WHO classification (Table 23.1) [17]. Two cases of primary cutaneous B-lymphoblastic lymphoma with different genetic changes have been reported in adult patients (one with rearrangement of the MLL gene and the other with hyperdiploidy), showing that various molecular subtypes of lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma may involve the skin [18].

Table 23.1 Classification of precursor lymphoid neoplasms according to the WHO [17]

|

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of cutaneous B-lymphoblastic lymphoma includes several entities that may show similar morphologic features. Mantle cell lymphoma contains cells with more cleaved or irregularly shaped nuclei and with a characteristic immunophenotype (CD5+, cyclin-D1+, CD10−, TdT−) (see Chapter 15). Myelogenous leukemia shows a proliferation of immature myeloid cells with figurate or “Indian-line” patterns that stain positive for myeloid markers (e.g., CD68 and myeloperoxidase among others) and do not reveal a monoclonal rearrangement of the Ig genes (see Chapter 20). Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm is characterized by a strong positivity for CD4 and CD56 in addition to a variable positivity for TdT, as well as by lack of rearrangement of the Ig genes (see Chapter 21). The differential diagnosis may also include cutaneous Merkel cell carcinoma and metastatic neuroendocrine carcinomas, which are characterized by the co-expression of cytokeratin filaments, neurofilament proteins, and various other neuroendocrine markers (e.g., chromogranin-A, synaptophysin), in addition to the lack of expression of lymphoid markers and the absence of Ig genes rearrangement.

Treatment and Prognosis

These patients should be managed in a hematologic setting. The treatment of choice is systemic chemotherapy, often followed by stem cell transplantation. Patients with localized skin disease appear to have a relatively good prognosis and seem to respond well to systemic chemotherapic regimens, but treatment strategies should be the same as for systemic variants of the disease.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree