Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm is the hematologic neoplasm that has changed most names during the years. In the last edition of this book the synonym “CD4+/CD56+ hematodermic neoplasm” was still mentioned, but at present there is general consensus on the term “blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm” used in the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues [1]. Neoplastic cells differentiate toward a common myeloid and lymphoid cell precursor, identified as the plasmacytoid type 2 dendritic cell [2–4], and a large study confirmed that the tumor originates from resting plasmacytoid dendritic cells of myeloid origin [4a]. Malignant transformation occurs at a very early stage of differentiation; thus the blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm belongs to the precursor hematologic neoplasms.

A relationship between blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm and myelogenous leukemia exists [5–8], and in the WHO classification blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm is listed in the section on acute myeloid leukemia and related precursor neoplasms [1]. Evolution into myeloid leukemia or association with previous myelodysplastic syndrome has been documented in some patients [9]. In spite of the putative relationship, however, studies by comparative genomic hybridization have revealed different profiles of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm and cutaneous lesions of myelogenous leukemia [10].

In most cases, blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm is confined to the skin at presentation or skin lesions represent the first manifestation of the disease [1, 11–14]. Leukemic spread after variable (usually short) periods of time is the rule, indicating that primary cutaneous cases most likely represent examples of so-called “aleukemic leukemia cutis” [15]. The identification of non-neoplastic plasmacytoid monocytes within the skin provides a theoretical background to the frequent finding of lesions confined to cutaneous sites [16].

Clinical Features

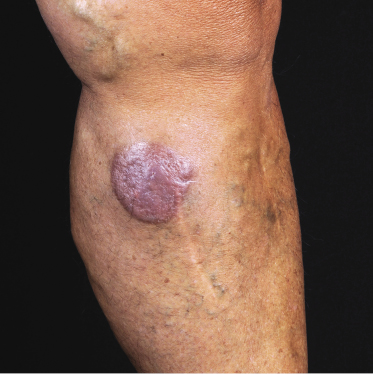

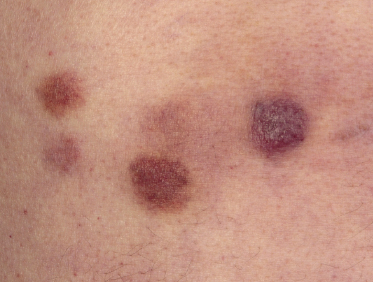

Patients are mostly adults and elderly, although cases in younger individuals, including small children, have been reported [12–15, 17–21]. There is a predominance of males. Clinically, they present with solitary, localized, or generalized plaques and tumors (Figs 21.1 and 21.2). A characteristic “bruise-like” violaceous aspect due to intratumoral hemorrhage is observed in several cases and early lesions may resemble localized areas of hemorrhage (Fig. 21.3). Ulceration is uncommon. Mucosal regions may be involved. In a distinct proportion of patients (approximately 30–40%), skin lesions are accompanied by general symptoms and extracutaneous manifestations in the blood, bone marrow, and/or other organs. Lymph nodes are involved in approximately half of the cases at presentation. Thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia are commonly found.

Cutaneous lesions are the first manifestation of the disease in over 90% of patients. In patients with primary cutaneous involvement, the time interval between the onset of skin lesions and leukemic spread is variable, usually between a few weeks and several months. Only rarely the disease remains confined to the skin for longer than one year.

Histopathology, Immunophenotype, and Molecular Genetics

Histopathology

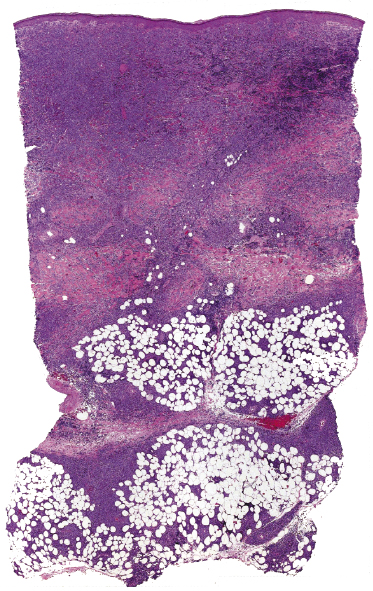

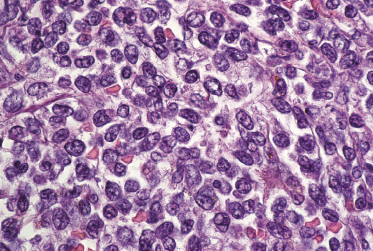

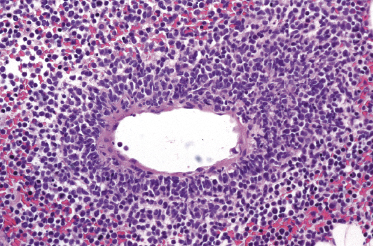

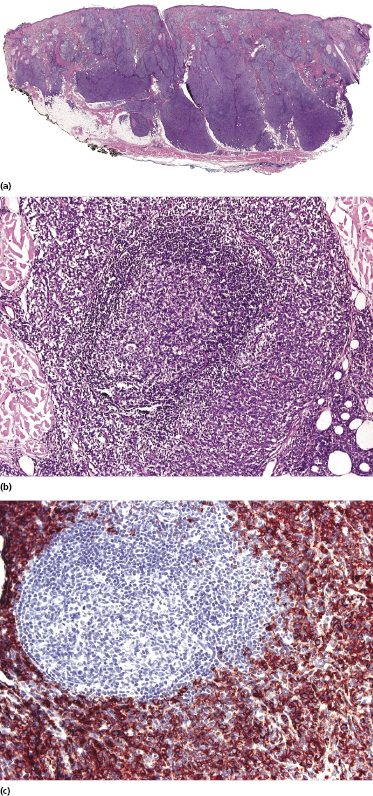

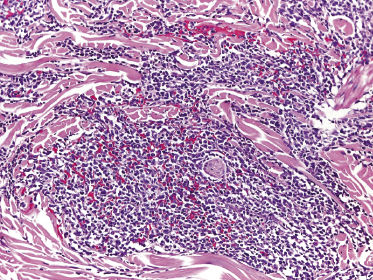

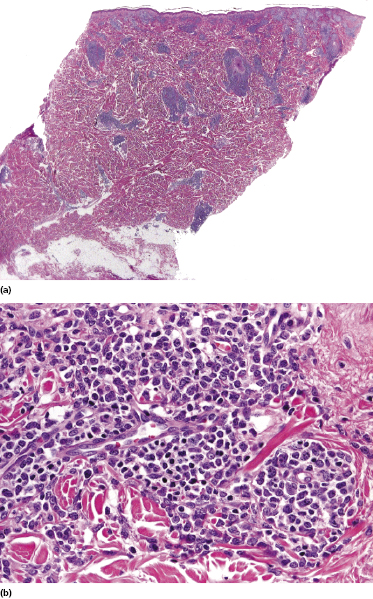

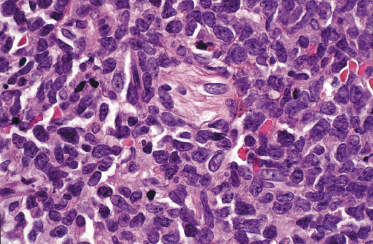

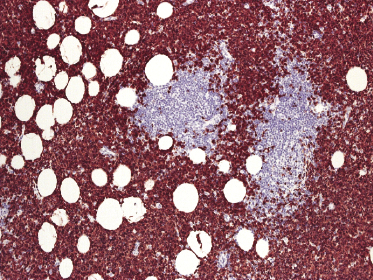

Histologically, blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm is characterized by a diffuse, monomorphous infiltrate of medium-sized neoplastic cells with a blastoid morphology (Figs 21.4 and 21.5). The epidermis is not involved as a rule, whereas involvement of the subcutaneous tissues is common. Angiocentricity and/or angiodestruction, necrosis, and granulomatous reactions can be found but are uncommon (Fig. 21.6). An inflammatory infiltrate with reactive germinal centers can be observed in a minority of cases (Fig. 21.7). Intratumoral hemorrhage is common and prominent in cases characterized by a bruise-like presentation clinically (Fig. 21.8).

In early lesions there are perivascular infiltrates of blastoid cells, sometimes admixed with reactive lymphocytes (Fig. 21.9). Sometimes I have observed peculiar morphologic features characterized by a certain degree of pleomorphism of the neoplastic cells, which showed elongated and twisted nuclei resembling large centrocytes of follicle center lymphoma (Fig. 21.10). Since Bcl-6 and multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM-1) may be positive in a proportion of cells in blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, and as reactive germinal centers may be present as well, these morphologic features may be the source of a diagnostic pitfall.

Immunophenotype

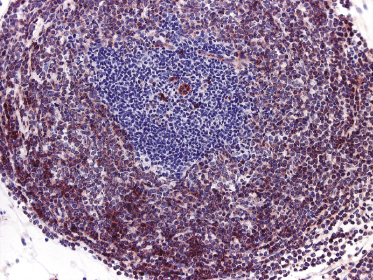

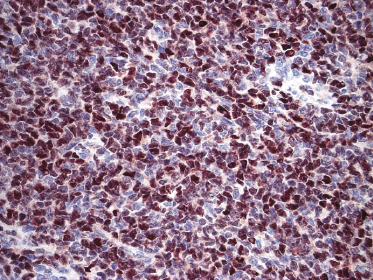

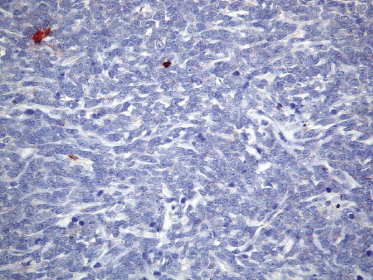

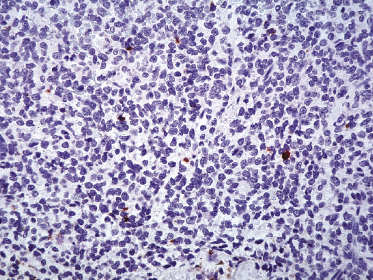

Neoplastic cells express CD4, CD56, and CD123 (Figs 21.11 and 21.12). TdT is positive in the majority of cases in a variable proportion of the cells (Fig. 21.13), whereas myeloid antigens, NK-cell markers, and cytotoxic proteins are negative (Figs 21.14 and 21.15) [22, 23]. Expression of CD123 underlines the relationship with plasmacytoid dendritic cells 2 [24], while the positivity for TdT confirms the origin from a precursor cell. Although the previous term adopted for this entity was “CD4+/CD56+ hematodermic neoplasm,” cases negative for CD4 have been recorded [25–27] and CD56 can be negative as well [25–29]. As CD123 may also be negative in some cases [25], the three markers most widely used for diagnosis of this rare entity should always be used together and in conjunction with a broad panel of antibodies directed toward lymphoid and myeloid antigens, keeping in mind that only integration of all stainings can allow a precise diagnosis. In this context, it should be remembered that myeloid leukemia is also positive for CD4 and may be positive for CD56 and CD123 as well. In the differential diagnosis between skin manifestations of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm from those of myeloid leukemia, these three antibodies should be used together with T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (TCL)-1 and blood dendritic cell antigen 2 (BDCA-2, CD303), which are positive in blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm but usually negative in myelogenous leukemia (Fig. 21.16). TCL-1 is a marker related to the proto-oncogene TCL1, which was demonstrated in the majority of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasms as well as in nodal plasmacytoid dendritic cells [24, 30, 31].

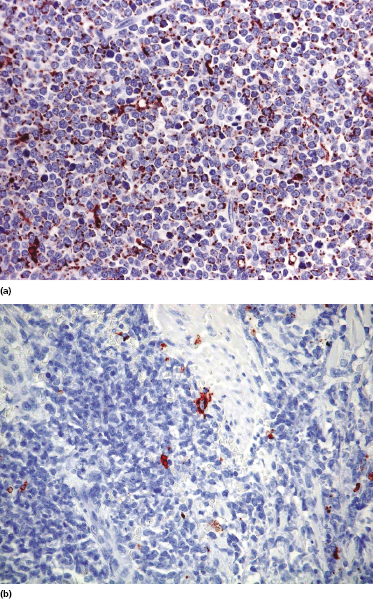

Cases positive for CD68 have been reported (Fig. 21.17a), but in my experience CD68 is usually negative (Fig. 21.17b) [4, 12, 22, 23]. Neoplastic cells in a proportion of cases may be positive for CD2, CD7, and CD45Ra. Other markers expressed in blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm are Bcl-2, CD43, CD101, BCL11A, CD2AP, ICSBP/IRF8, and HLA-DR [32–35]. In some cases I have also observed focal positivity for Bcl-6 and MUM-1, which can be misleading if not evaluated in the proper context.

The pattern of expression of nucleophosmin, an estrogen-regulated nucleolar protein that is expressed in a mutated form in the cytoplasm in one-third of the cases of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia, differs between blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasms (nuclear pattern) and myelogenous leukemia (cytoplasmic pattern) [36].

Molecular Genetics

Molecular genetic studies reveal that the T-cell receptor (TCR) and immunoglobulin (Ig) genes are in germline configuration, but exceptional cases with TCR gene rearrangement have been observed [37, 38]. Thus, although for practical purposes a monoclonal rearrangement of the TCR and/or Ig genes rules out the diagnosis of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, care should be taken in the interpretation of molecular results. One potential pitfall may be represented by the presence of small oligoclonal populations of reactive T and B lymphocytes within the infiltrate.

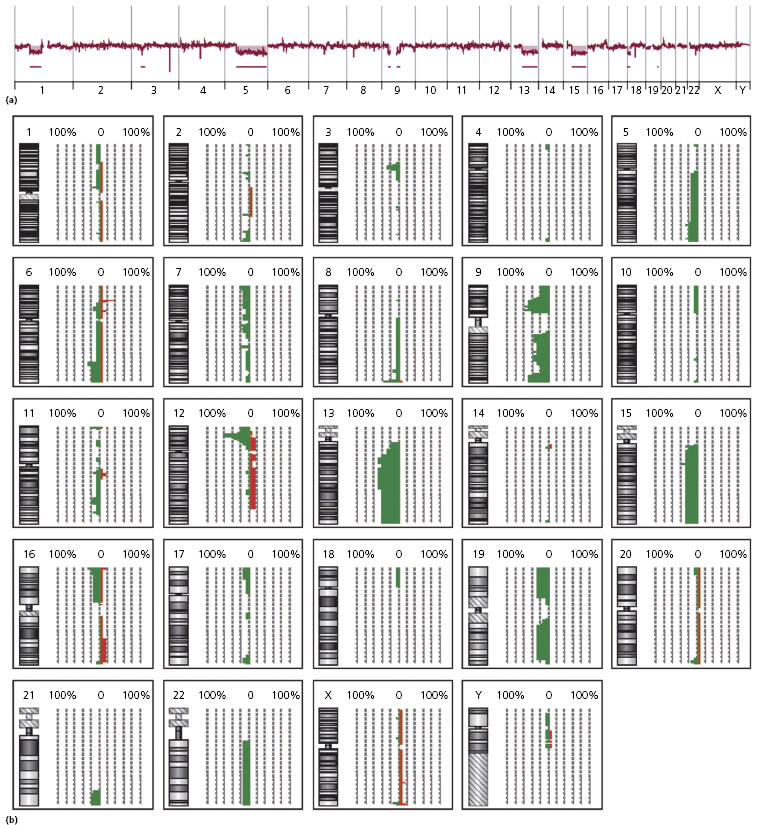

Complex karyotypes and chromosomal abnormalities involving chromosomes 5q, 6q, 12p, 13q, 15q, and 9 have been observed in blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm [2]. Gain of chromosomes 7q and 22 and loss of chromosomes 3p and 13q was demonstrated by comparative genome hybridization in one study [39], while recurrent deletion of regions on chromosome 4 (4q34), chromosome 9 (9p13–p11 and 9q12–q34), and chromosome 13 (13q12–q31) was found in another study [10], and losses of 9/9p and 13q and gain of 7 in a third [40]. The least common denominator of these studies seems to be the presence of abnormalities involving chromosomes 9 and 13 (Fig. 21.18), confirmed by subsequent studies showing aberrations located at the 9p21.3 (CDKN2A/CDKN2B), 13q13.1-q14.3 (RB1), 12p13.2-p13.1 (CDKN1B), 13q11-q12 (LATS2), and 7p12.2 (IKZF1) regions [41–43]. The dose-dependent haploinsufficient cell-cycle inhibitor p27KIP1, encoded by CDKN1B, is weakly expressed in the nuclei of tumor cells in most cases, and the cell-cycle inhibitor p16INK4a, which is encoded by CDKN2A, was not expressed in tumor cells, suggesting a complete loss of function. [42]. These results imply that alterations of the cell-cycle checkpoint controlling proteins p27KIP1, p16INK4a, and RB1 may exert a crucial effect in malignant transformation in blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasms. Aberrant activation of the NF-kb pathway was demonstrated in a large study, suggesting that it may represent a novel therapeutic target [4a].

Whole-exome-sequencing analysis of three cases of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasms confirmed the relationship to the myeloid leukemias [44].

Treatment

Treatment of patients with blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm should be carried out in a hematologic setting. Although systemic chemotherapy is usually followed by rapid, complete primary responses, remissions are short and recurrences are the rule [45]. Good response has been observed also with L-asparaginase in association with methotrexate and dexamethasone [46]. The only curative option, however, seems to be allogeneic stem cell transplantation [9, 47–49]. Patients presenting with primary cutaneous disorder should be treated in the same aggressive manner.

Prognosis

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm is a very aggressive disorder and the prognosis is very poor. The estimated 5-year survival is 0% [50]. Patients usually succumb within 1 year from first diagnosis. Although presentation with solitary or localized skin lesions may be associated with a less aggressive course, at present there is no evidence that long-term survival can be achieved with conventional treatments, even for these patients. As already mentioned, allogeneic bone marrow transplantation yields better results and should be offered as the first therapeutic option whenever possible [9, 47−49].

Young age (<40 years) and TdT expression in >50% of the neoplastic cells were independent prognostic variables associated with a better prognosis in one study [33], confirmed by the subsequent finding of better survival in pediatric cases [21]. Skin involvement seems to represent an unfavorable prognostic sign both in children and adult patients [21, 51]. As already mentioned, however, cutaneous manifestations are found in the vast majority of cases. Longer survival was associated with CD303 expression and high proliferative index (Ki-67) in a large study [52]. A poor outcome was observed in patients with biallelic loss of locus 9p21.3 [41].

Full access? Get Clinical Tree