Mycosis Fungoides

Mycosis fungoides is the most common type of cutaneous lymphoma, representing almost 50% of all lymphomas arising primarily in the skin [1–3]. It is defined as a tumor composed of small/medium-sized, epidermotropic T-helper lymphocytes (but T-cytotoxic variants are not uncommon and tumor cells may be medium/large in advanced stages).

Mycosis fungoides is the oldest entity in the field of cutaneous lymphomas, having been described more than two centuries ago, in 1806, by the French dermatologist Alibert. Traditionally it is divided into three clinical phases: patch, plaque, and tumor stage. The clinical course can be protracted over years or decades. In the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues the term “mycosis fungoides” is restricted to the classic type of the disease (so-called “Alibert–Bazin”), characterized by the typical slow evolution and protracted course [3]. It is estimated that over 90% of patients with early mycosis fungoides neither progress to tumor stage nor show extracutaneous manifestations of the disease [4, 5]. In the WHO classification it is stated that “Patients with limited disease generally have an excellent prognosis with a similar survival as the general population” [3]. Phenotypic and genetic studies showed that entities described in the past as “rapidly progressive” mycosis fungoides (e.g., mycosis fungoides a tumeur d’emblée, generalized pagetoid reticulosis – Ketron–Goodman) are better classified among the group of aggressive cutaneous cytotoxic natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphomas (see Chapter 6).

The incidence of the disease worldwide is probably around 6–7 cases/106, with many regional variations and with a regular increase in recent decades [6, 7]. A stabilization of the incidence has been noted in the United States in the period 1998–2009 [8]. There is a higher incidence in black patients [9] and the average age of onset seems to be younger for black than for white patients [10].

In spite of decades of research, the etiology of mycosis fungoides remains unknown. A genetic predisposition may play a role in some cases and a familial occurrence of the disease has been reported in a few instances [11]. A study conducted among Israeli Jewish patients showed a significantly greater allele frequency of HLA DQBI*03, suggesting that genetic factors may play a role in the etiology of the disease, at least in selected groups of patients [12]. On the other hand, mycosis fungoides has been rarely observed in unrelated married individuals, pointing to the existence of possible environmental factors [13]. Association with long-term exposure to various allergens and association with chronic skin disorders have also been suggested as possible etiologic factors, but no epidemiologic study confirmed these hypotheses beyond doubt. A relationship with Borrelia burgdorferi infection, human T lymphotropic virus I (HTLV-I), cytomegalovirus (CMV), human herpes virus (HHV)-6, HHV-8, Merkel cell polyoma virus (MCPyV), and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) has also been investigated, but so far a link to infectious agents could not be demonstrated [14]. Interestingly, mycosis fungoides has been observed rarely in patients who received solid organ transplantation, suggesting that immune suppression may contribute to the development of the disease [15, 16].

Genetic alterations have been identified mainly in late stages of the disease, and their importance for disease initiation is unclear. Activation of genes belonging to pathways associated with inflammation, immune activation, and regulation of apoptosis have been identified in the early phases, but also in chronic inflammatory dermatoses [17].

Mycosis fungoides has been described in patients with other cutaneous or extracutaneous hematologic disorders, especially lymphomatoid papulosis and Hodgkin lymphoma. In occasional patients, the same clone has been detected in mycosis fungoides and associated lymphomas, raising questions about a common origin of the diseases, while in others the clone was different [18–21]. In addition, patients with mycosis fungoides are at higher risk of developing a second (nonhematologic) malignancy [22].

A staging classification system for mycosis fungoides was proposed by a joint working group of the International Society of Cutaneous Lymphoma (ISCL) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force (Table 2.1) [23]. This system has been validated by a study on large numbers of cases [24]. In patients presenting only with patches of the disease (early mycosis fungoides) staging investigations are not necessary and only clinical examination is performed (assessment of the percentage of body involvement and of superficial lymph nodes). A bone marrow biopsy is not necessary in early mycosis fungoides and results of real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analyses do not support its routine use at this stage [25]. Patients with infiltrated plaques, tumors, or erythroderma should be screened for extracutaneous involvement (laboratory investigations, sonography of lymph nodes, CT and/or PET scan of chest, abdomen and pelvis, bone marrow biopsy, examination of the peripheral blood). Suspect lymph nodes (lymph nodes that are either >1.5 cm in diameter and/or irregular, clustered, or fixed) should be biopsied. Although the presence of a monoclonal population of T lymphocytes within the peripheral blood has been observed by the PCR technique in some patients with early mycosis fungoides, in many of these cases the clone was different from the one detected in the skin lesions [26]. Evaluation of the peripheral blood is crucial in erythrodermic patients with suspect Sézary syndrome, but of little relevance in those with patches of early mycosis fungoides.

Table 2.1 Staging of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome according to the ISCL–EORTC

Many studies have addressed the identification of clinical markers of the disease, but at present there is no investigation other than conventional physical examination and radiologic imaging that can allow reliable and repeatable monitoring of mycosis fungoides, particularly in the early stages. Several markers have been the subject of investigations, including cancer antigen 27.29 (CA27.29) [27], transthyretin [28], peripheral blood mononuclear cell cytokine expression [29], circulating CD8+ lymphocytes [30], testis-specific protein 10 (TSGA10) [31], and B-cell activating factor (BAFF) [32] among others, but their value, if any, is yet unclear. Flow cytometry immunophenotyping and analysis of T-cell receptor Vβ repertoires is effective in demonstrating and quantifying small numbers of circulating tumor cells in patients with mycosis fungoides [33].

The relationship between mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome has been the subject of innumerable studies. In the past, Sézary syndrome was considered as the leukemic variant of mycosis fungoides, and both entities were lumped in the nonspecific group of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). Indeed, this term is still being used in publications on the subject, particularly in studies carried out in the United States. Although the term CTCL has helped focus the attention on a group of lymphomas arising primary in the skin, its use should be discouraged, and cases should be classified according to precise categories. In fact, there are phenotypic and genetic data supporting the distinction of mycosis fungoides from Sézary syndrome [34, 35]. Mycosis fungoides is a disease of skin resident, effector memory T-cells, whereas Sézary syndrome is a malignancy of central memory T-cells [36].

One of the main subjects of discussion in mycosis fungoides is the relationship with the so-called “parapsoriases.” More than one hundred years after the introduction of the term by Brocq (who, by the way, proposed the term only as a provisional nomenclature!) there is still no consensus as to how to classify these lesions. Some consider parapsoriasis en plaque as a precursor of the disease, others as an early manifestation of it, and still others as a differential diagnosis of mycosis fungoides. A thorough discussion on the parapsoriases can be found in a specific section later in this chapter.

Clinical Features

Lesions of mycosis fungoides can be divided morphologically into patches, plaques, and tumors, and clinical morphology has been used in the past to classify the disease in three clinical stages according to the presence of such lesions. These three “stages” reflect disease activity and correlate well with prognosis. In fact, although patches and plaques are considered as a single morphologic criterion in the ISCL–EORTC staging system, a large study clearly showed that the presence of plaques is associated with a worse prognosis in terms of survival and progression risk as compared with that of patches only [24].

Although patches are considered as a clinical feature of early mycosis fungoides, it should be underlined that patients with advanced mycosis fungoides who are in complete remission after successful treatment may relapse with either patches, plaques, or tumors, and that patches are frequently seen in patients with advanced (tumor-stage) mycosis fungoides.

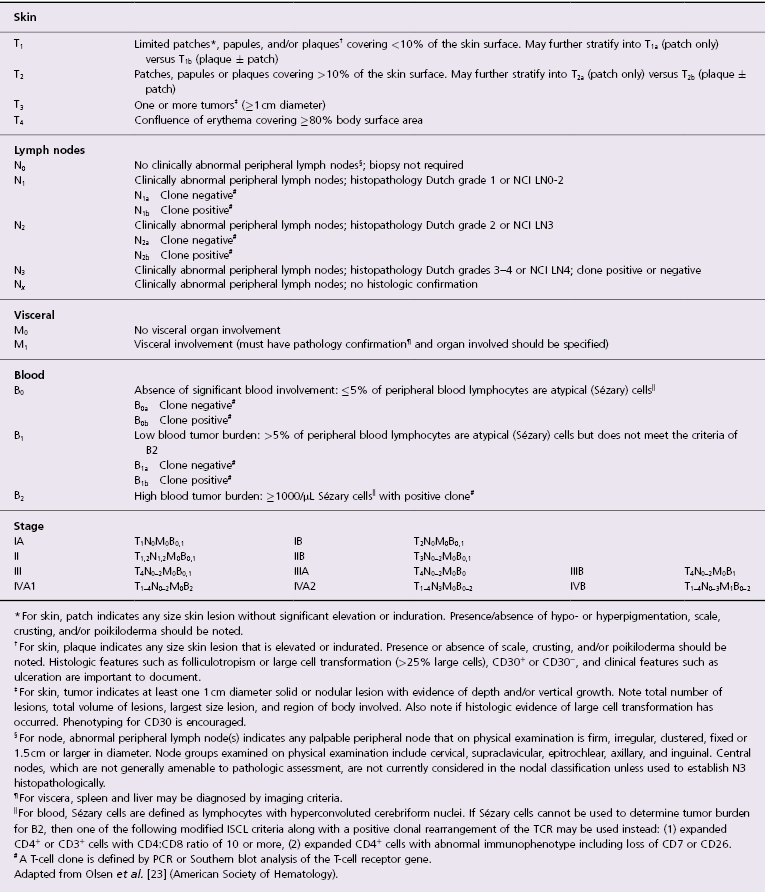

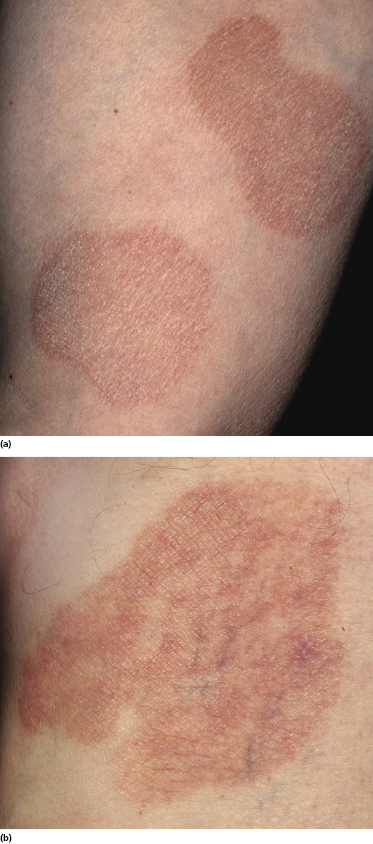

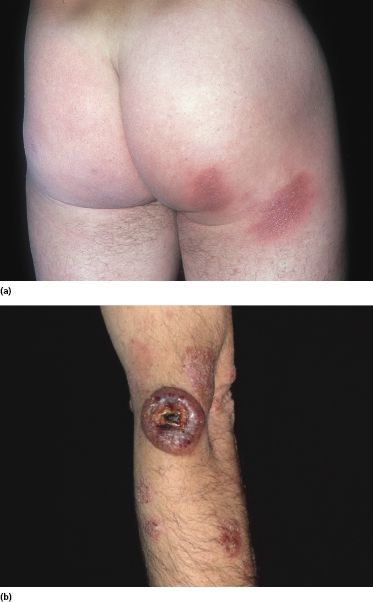

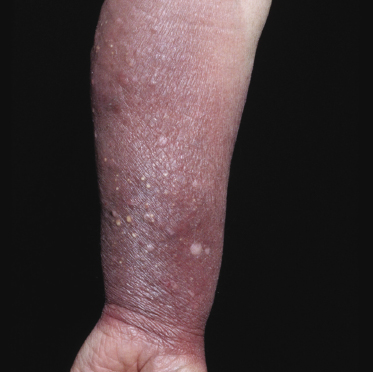

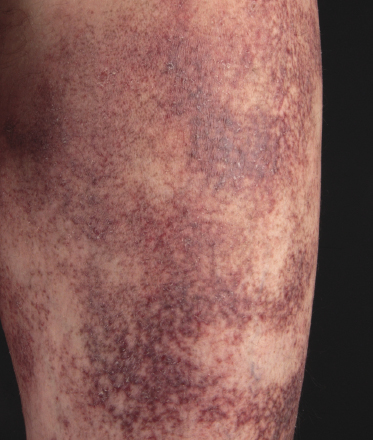

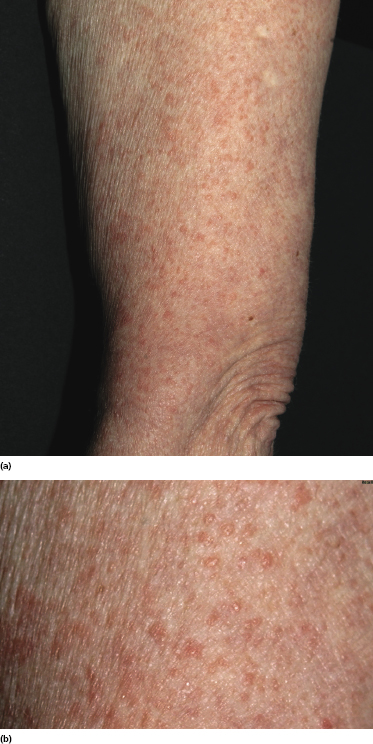

Patches of mycosis fungoides are characterized by variably large, erythematous, finely scaling lesions. They can be generalized or localized (Fig. 2.1); when localized, there is often a predilection for the buttocks and other sun-protected areas (Figs 2.2 and 2.3). Scaling is variable and may also depend on previous local treatment (Fig. 2.4). Loss of elastic fibers and atrophy of the epidermis may confer on the lesions a typical wrinkled appearance, and terms such as ‘parchment-like’ or ‘cigarette paper-like’ have been used to describe them. These morphological features are particularly frequent in poikilodermatic mycosis fungoides (see the corresponding section in this chapter). Sometimes the single patches have a yellowish hue, conferring a “xanthomatous”-like aspect to the lesions (in the past referred to as “xanthoerythroderma perstans”) (Fig. 2.5).

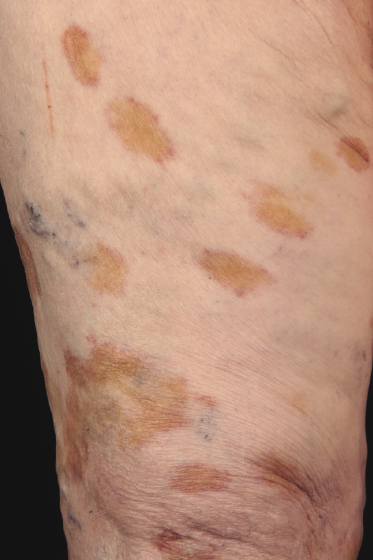

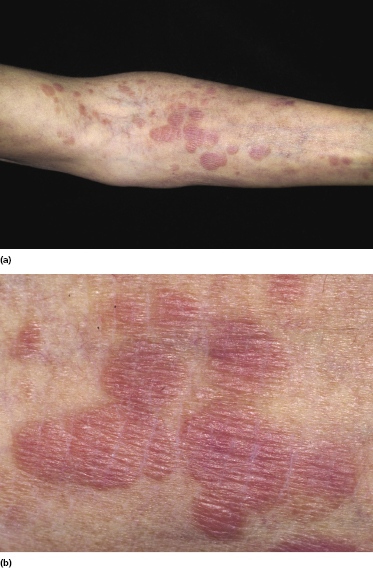

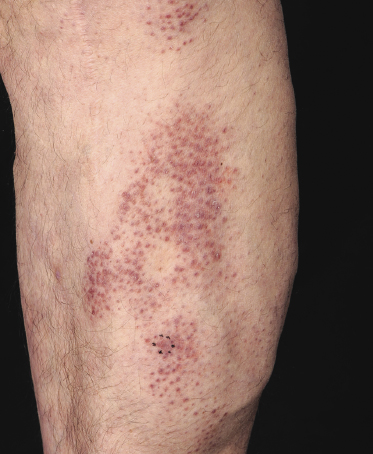

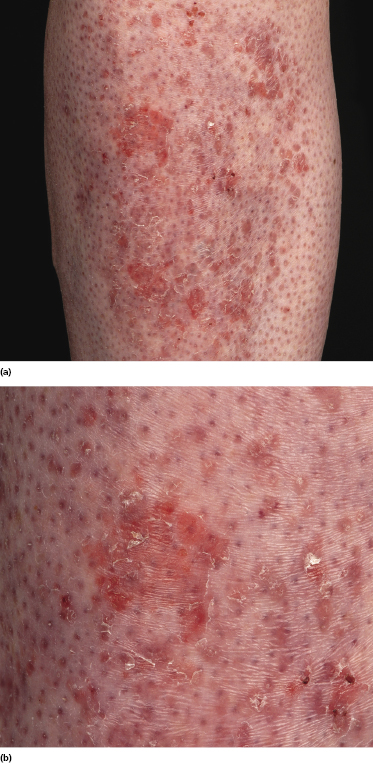

Plaques of mycosis fungoides are characterized by infiltrated, variably scaling, reddish-brown lesions (Figs 2.6 and 2.7). Typical patches are usually observed contiguous to plaques or at other sites of the body. The size and form of the plaques are variable. Ulceration may be present but it is usually confined to a portion of the lesion; in some cases superficial crusts convey some resemblance to impetiginized lesions (and secondary impetiginization may also occur). Plaques of mycosis fungoides should be distinguished from flat tumors of the disease (Fig. 2.8).

Patches and plaques of mycosis fungoides may have a different morphology on dark skin (“skin of color”). Besides the hypopigmented variant, which is seen more often in black patients, lesions usually appear less erythematous and have a greyish or silver hue instead (Fig. 2.9). Both hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation may be present, often at the same time.

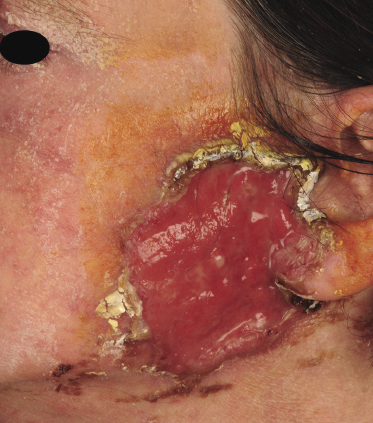

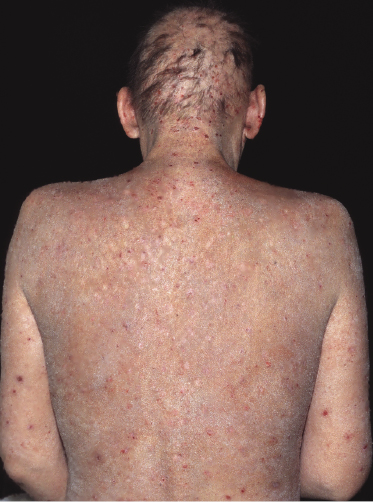

Tumors in mycosis fungoides may be observed in the absence of other lesions, or in combination with patches and plaques (Figs 2.10, 2.11, and 2.12). They may be solitary or, more often, localized or generalized. Ulceration is common. Large ulceration of flat tumors may mimic the picture of so-called ulcus rodens (Fig. 2.13) and fungating tumors may destruct underlying structures (Fig. 2.14). Flat tumors and associated plaques may present as large, marginated, sometimes “geographical” lesions (Fig. 2.15). On the scalp, confluent, flat tumors may confer on the lesion features similar to those of “cutis verticis gyrata” (Fig. 2.16). The growth rate of tumors in mycosis fungoides is variable: in some cases they grow rapidly in a matter of weeks, in others they are relatively stable for months. Partial regression is not uncommon.

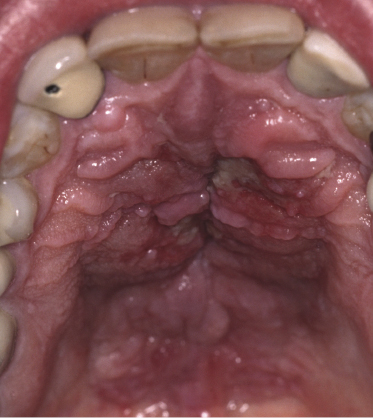

Besides the skin, tumors of mycosis fungoides may involve the mucosal regions (Fig 2.17). Involvement of the mucosal surfaces is very unusual in the early phases, but less so in advanced stages. As oral and genital mucosa are frequently involved in cytotoxic NK/T-cell lymphomas, care should be taken to classify these cases correctly. Precise clinical history taking, re-evaluation of previous biopsies, and complete phenotypic and genotypic investigations are mandatory to make the diagnosis of mucosal involvement in mycosis fungoides.

Itching is often a prominent symptom in all stages of the disease and may be very difficult to treat [37]. Onychodystrophy may be prominent in advanced mycosis fungoides [38]. Erythroderma can develop in the course of the disease, rendering distinction from Sézary syndrome difficult without a proper clinical history (see also the section on erythrodermic mycosis fungoides in this chapter and Chapter 3). The palms and soles may be affected in some patients, either with diffuse or with patchy, scaly erythema (Fig. 2.18). Involvement of these regions is more common in the syringotropic variant of the disease. Tumors in acral locations are not unusual and sometimes represent the first sign of disease’s progression (Fig. 2.19).

Clinical variants of mycosis fungoides are discussed in specific sections in this chapter.

Extracutaneous Involvement

Lymph nodes, lung, spleen and liver are the most frequent sites of extracutaneous involvement in mycosis fungoides, but specific lesions can arise in all organs [39]. The bone marrow is usually spared. Lymph node involvement may be difficult to differentiate histopathologically from so-called dermopathic lymphadenopathy, and it has been demonstrated that, irrespective of the histopathologic features, enlarged lymph nodes represent a bad prognostic sign [24].

Because of the presence of ulcerated tumors and immune deficiency (due to both the lymphoma and the many treatments typically administered to these patients during the course of the disease), septicemia and/or pneumonia are the major causes of death.

Association with Other Diseases

As mentioned before, mycosis fungoides can be observed in association with other hematological diseases such as lymphomatoid papulosis, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, and Hodgkin lymphoma. Onset of these disorders may precede, be concomitant with, or occur later than the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides. It may be extremely difficult (if not impossible) to differentiate tumor-stage mycosis fungoides from lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis and anaplastic large cell lymphoma (see also Chapter 4). Some of the cases reported as lymphomatoid papulosis or cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma arising after the onset of mycosis fungoides may in fact represent lesions of tumor-stage mycosis fungoides with expression of CD30. In this context, it should be noted that spontaneous regression (usually partial regression) of single tumors of mycosis fungoides is not uncommon. Besides these disease entities, mycosis fungoides has been observed also in association with other non-Hodgkin lymphomas of T- or B-cell lineage [40–42]. In rare cases, mycosis fungoides may be associated with a second, unrelated lymphoma at the same skin site (“composite lymphoma”) (see Teaching case 19.1 in Chapter 19) [43].

An increased incidence of cancers other than lymphomas has been observed in patients with mycosis fungoides [40]. In these patients, mycosis fungoides may represent either the primary or the subsequent malignancy.

Specific infiltrates of mycosis fungoides can be observed in benign and malignant skin tumors such as melanocytic nevi, malignant melanoma, and seborrheic keratoses, among others (Fig. 2.20). In these cases the association of the two diseases represents an example of so-called “collision tumors,” due to colonization of a second neoplasm by neoplastic cells of mycosis fungoides (composite lymphomas are also conceptually a variant of “collision tumors”).

Histopathology, Immunophenotype, and Molecular Genetics

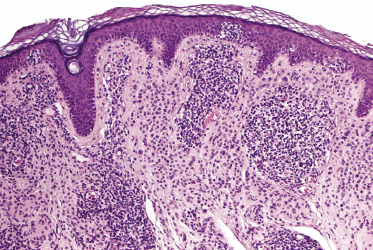

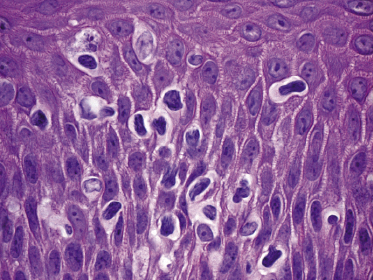

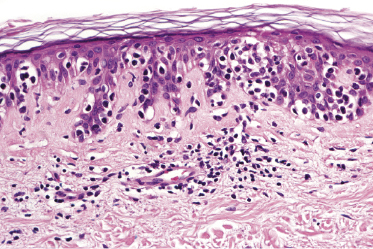

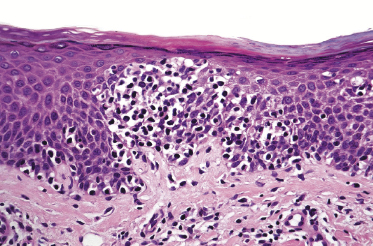

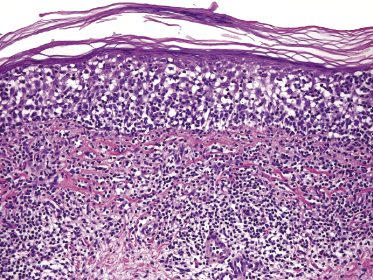

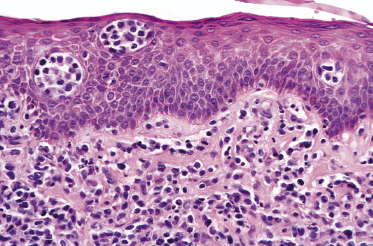

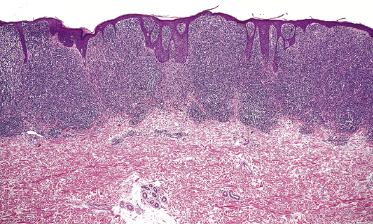

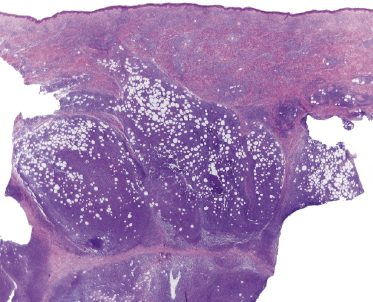

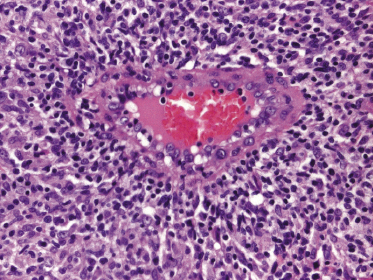

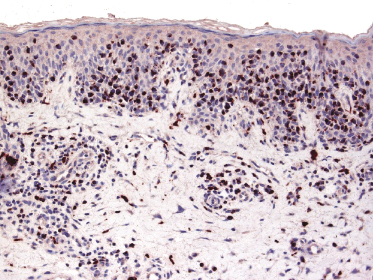

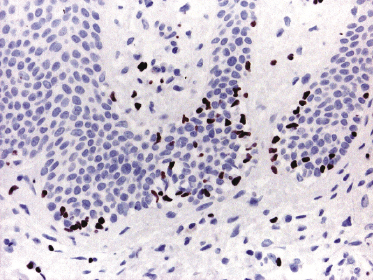

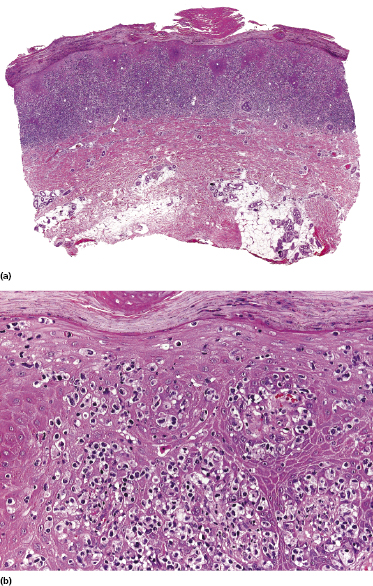

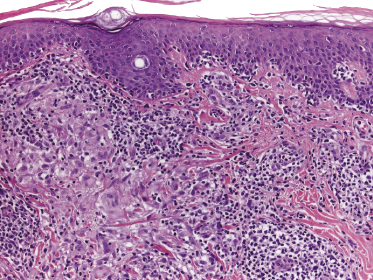

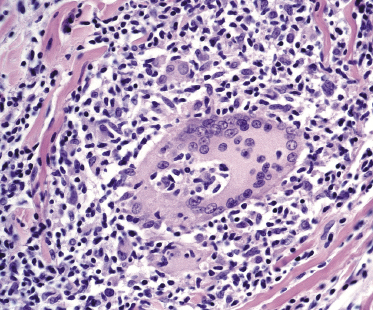

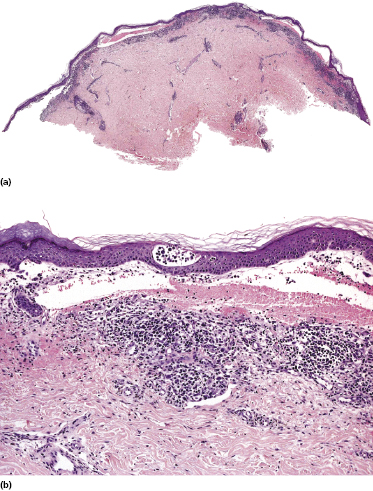

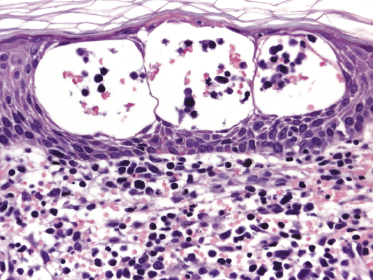

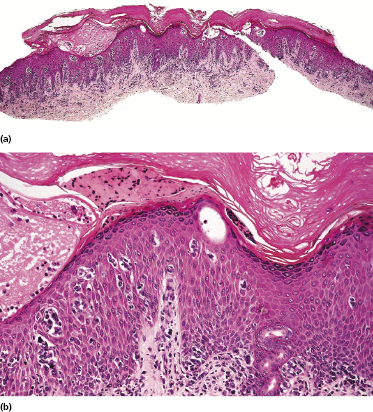

Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma characterized cytomorphologically by the proliferation of small- to medium-sized pleomorphic (“cerebriform”) lymphocytes (Fig. 2.21). Intraepidermal collections of lymphocytes (so-called “Pautrier’s microabscesses”) (Fig. 2.22), considered the hallmark of the disease, are present only in a minority of early patches of mycosis fungoides and can be absent from more advanced lesions as well. Parenthetically, the first description of the “microabscesses” was not by Pautrier but by Jean Ferdinand Darier several decades before [44]. Pautrier was puzzled by the attribution of this observation to himself and acknowledged that the intraepidermal collections of lymphocytes should have been termed “Darier’s nests” (a term that was used in the 1920s) instead [44].

It should be emphasized that, although precise histopathologic criteria for the diagnosis of early mycosis fungoides have been identified (Table 2.2), in many cases a definitive diagnosis can be made only after a careful correlation with the clinical features of the disease [45]. Further problems can arise when biopsies are taken after different types of local treatment that alter the histopathologic features of the lesions. As a general rule, it is advisable to take multiple biopsies from morphologically different lesions, if necessary to repeat biopsies after a 2-week period without local treatment, and to perform repeat biopsies on recurrent lesions. Repeat biopsies on recurrent lesions should be performed also to check whether the histopathologic features are stable or changing (i.e., occurrence of large cell transformation).

Table 2.2 Histopathologic criteria for the diagnosis of early mycosis fungoides

| Epidermis |

| Intraepidermal collections of lymphocytes (Darier’s nests / Pautrier’s microabscesses) |

| Lymphocytes aligned along the dermoepidermal junction |

| Intraepidermal lymphocytes larger than lymphocytes in the dermis |

| “Disproportionate” epidermotropism (epidermotropic lymphocytes with only scant spongiosis) |

| Intraepidermal lymphocytes with “haloed” nuclei |

| Dermis |

| Expanded papillary dermis with slight fibrosis and coarse bundles of collagen |

| Band-like or patchy-lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes |

Scoring systems and algorithms for the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides have been proposed, combining the clinical aspect with the immunophenotypic and molecular features of the infiltrate [46]. However, in my view and in that of others [47], the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides can be achieved in most cases by accurate clinicopathologic correlation, without the need of more or less complex algorithms. In this context, our group described several histopathologic patterns of early mycosis fungoides that were previously poorly characterized, showing the protean nature of the disease and the difficulties in histopathologic diagnosis [45].

Histopathology

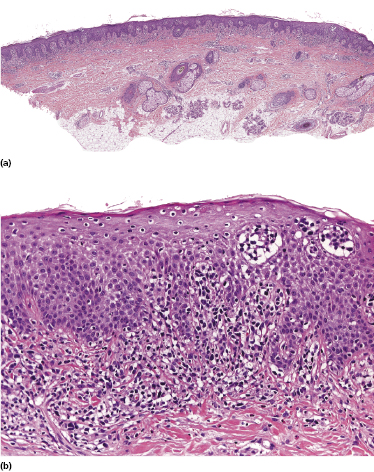

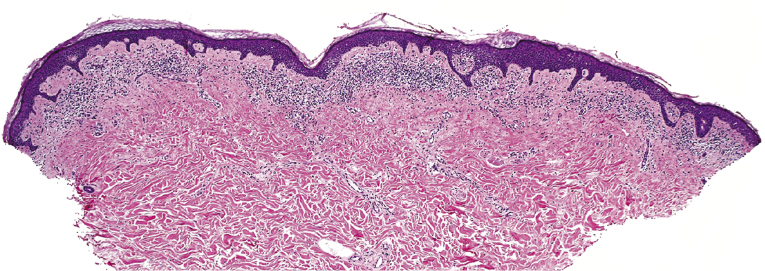

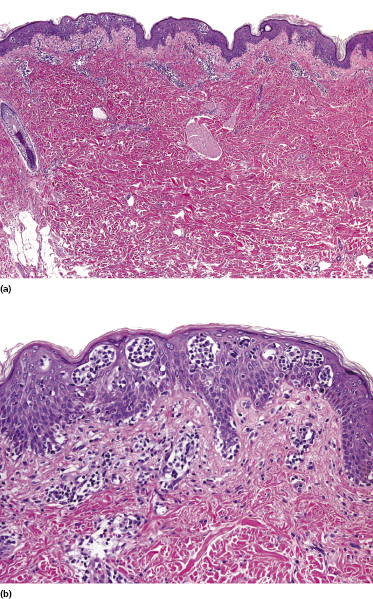

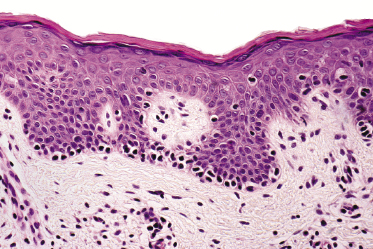

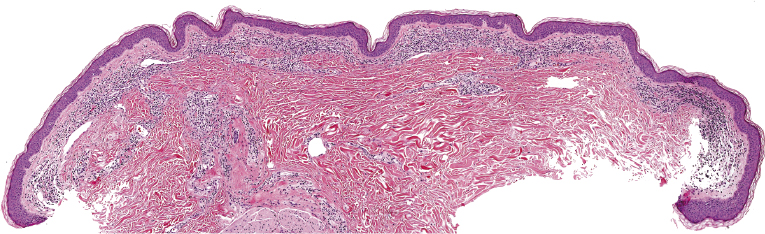

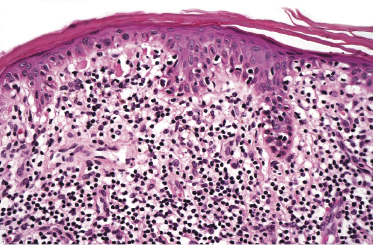

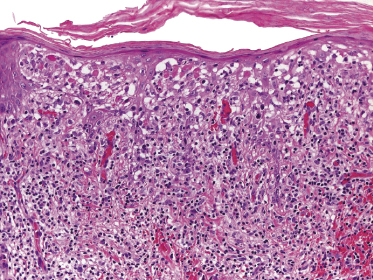

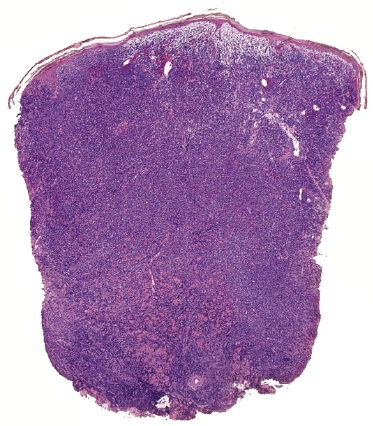

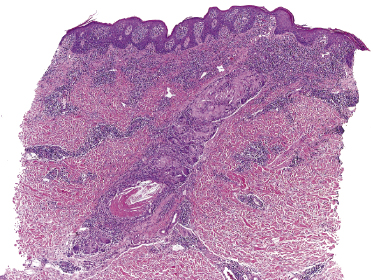

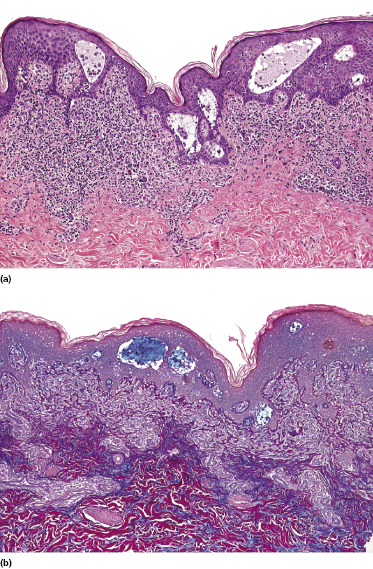

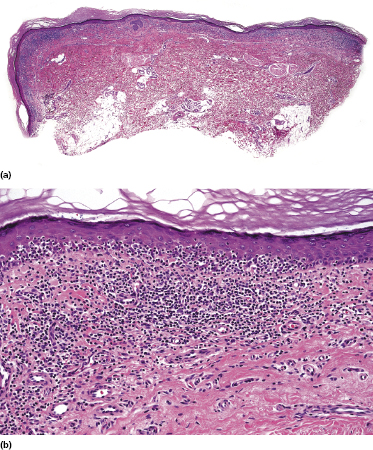

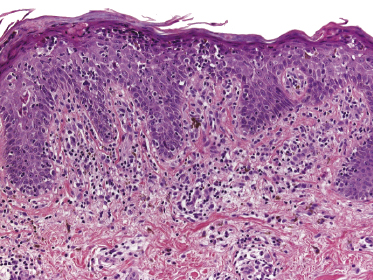

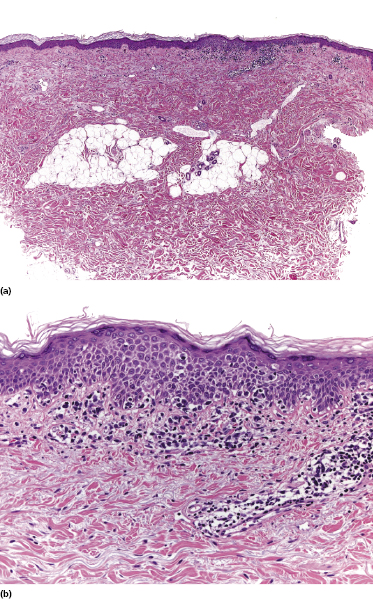

Early lesions of mycosis fungoides reveal in the vast majority of cases a patchy lichenoid or band-like infiltrate in an expanded papillary dermis (Fig. 2.23). The epidermis may be hyperplastic, normal or atrophic (Figs 2.22a and 2.24) (the epidermis is atrophic as a rule in poikilodermatous lesions). Small lymphocytes predominate and atypical cells can be observed only in a minority of cases. Epidermotropism of solitary lymphocytes is usually found (Fig. 2.21), but Darier’s nests (Pautrier’s microabscesses) are rare (Fig. 2.25). Useful diagnostic clues are the presence of epidermotropic lymphocytes with nuclei slightly larger than those of lymphocytes within the upper dermis (Figs 2.26), the presence of lymphocytes aligned along the basal layer of the epidermis (“basilar epidermotropism”) (Fig. 2.27), and the presence of many intraepidermal lymphocytes in areas with scant spongiosis (Fig. 2.28) [45, 48–52]. This last feature is referred to as “disproportionate” epidermotropism, because a few intraepidermal lymphocytes may be observed in areas of spongiosis in many inflammatory dermatoses. In this context, it should be emphasized that in a few cases (about 5% of the total) epidermotropism may be minimal or missing altogether (Fig. 2.29), most likely related to previous treatment (particularly if the diagnosis is not yet known, biopsies are often taken during therapy because of poor response of the lesions, and are submitted as “therapy-resistant dermatitis”) (see also Teaching case 2.3). Small foci of epidermotropism may be found in deeper sections in these cases. The papillary dermis shows a moderate to marked fibrosis with coarse bundles of collagen and a band-like or patchy-lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes. Dermal edema is usually not found. Eosinophils may be present (Fig. 2.22b), but they are not a common finding in patches and plaques of mycosis fungoides [53]. Langerhans cells are usually increased in the epidermis and dermis in early lesions of mycosis fungoides (see the section on immunophenotype in this chapter).

Unusual histopathologic patterns of mycosis fungoides in early phases include the presence of a perivascular (as opposed to band-like) superficial infiltrate (Fig. 2.25), prominent spongiosis (Fig. 2.30), sometimes with Darier’s nests (Pautrier’s microabscesses) mimicking spongiotic vesicles (Fig. 2.31), an interface dermatitis, sometimes with several necrotic keratinocytes similar to the picture of erythema multiforme (Figs 2.32 and 2.33), marked pigment incontinence with melanophages in the papillary dermis (see the section on hyperpigmented mycosis fungoides in this chapter), prominent epidermal hyperplasia like in lichen simplex chronicus (Fig. 2.34), prominent sclerosis of the papillary dermis mimicking lichen sclerosus (Fig. 2.35), and prominent extravasation of erythrocytes simulating the picture of lichenoid purpura (see the section on pigmented purpura-like mycosis fungoides in this chapter). A pattern characterized by a markedly flattened epidermis, a lichenoid infiltrate in the dermis, and increased, dilated vessels in the papillary dermis is the histopathologic counterpart of poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides (see the specific section in this chapter). In rare cases the histopathological features may resemble those observed in pityriasis lichenoides and varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) (see the specific section in this chapter). This last pattern is found more frequently in children.

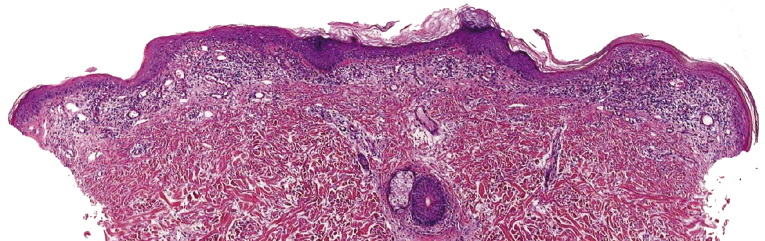

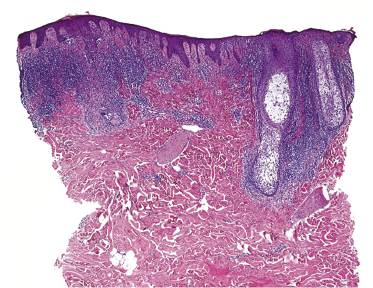

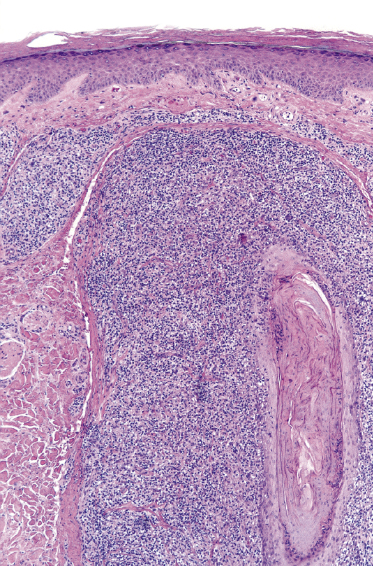

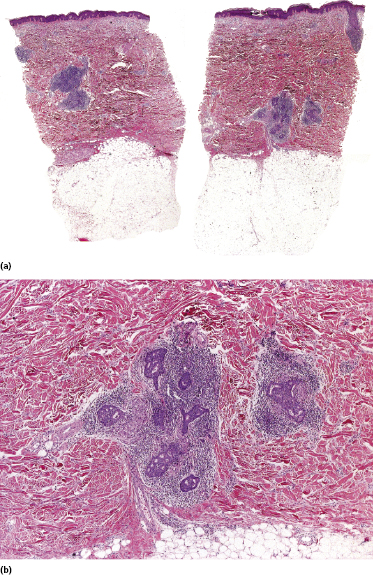

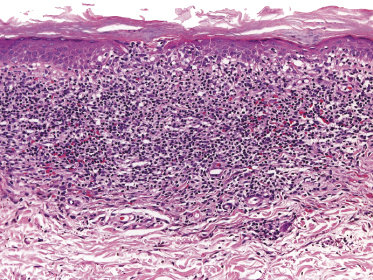

Plaques of mycosis fungoides are characterized by a dense, band-like infiltrate of lymphocytes within the upper dermis (Fig. 2.36). Intraepidermal lymphocytes arranged in Darier’s nests (Pautrier’s microabscesses) are a common finding at this stage (Fig. 2.37). Cytomorphologically, small/medium pleomorphic (cerebriform) cells predominate (Fig. 2.38).

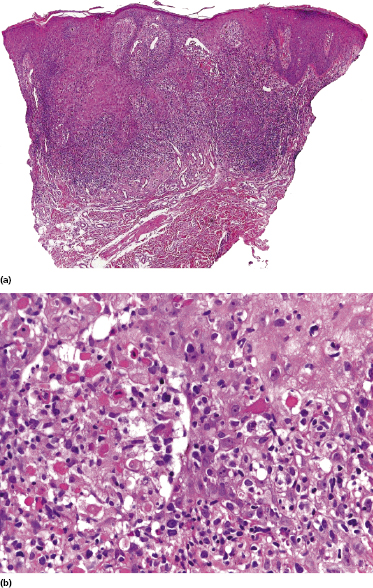

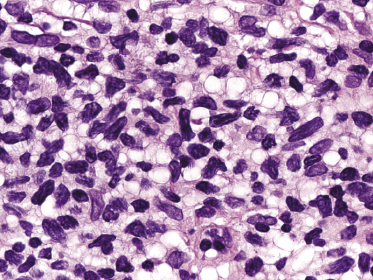

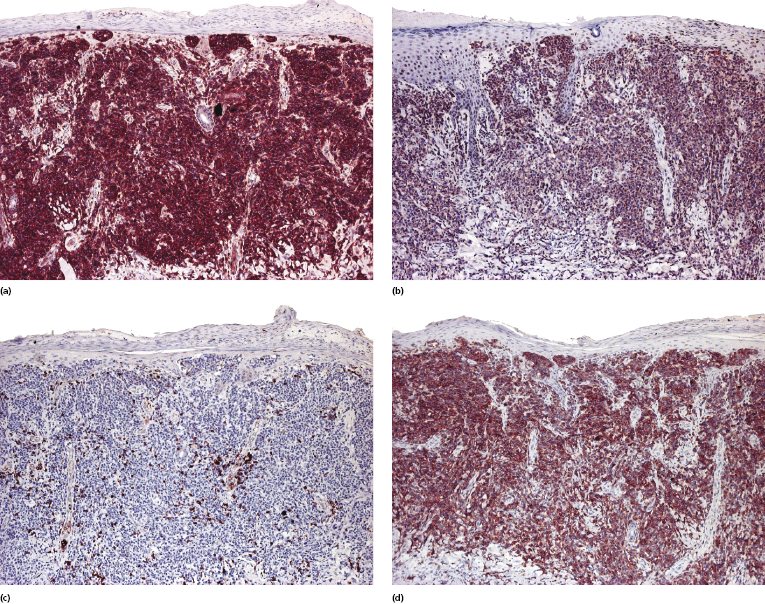

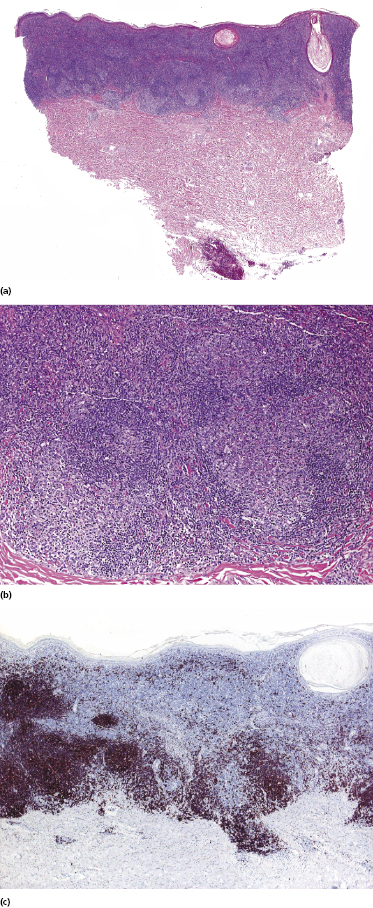

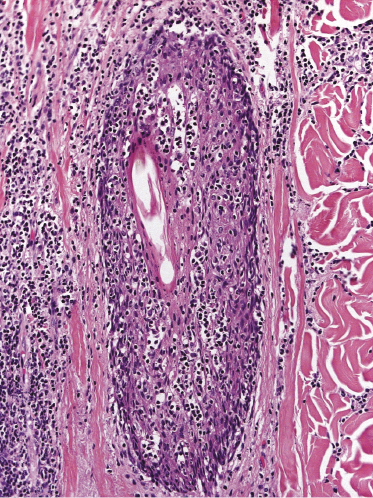

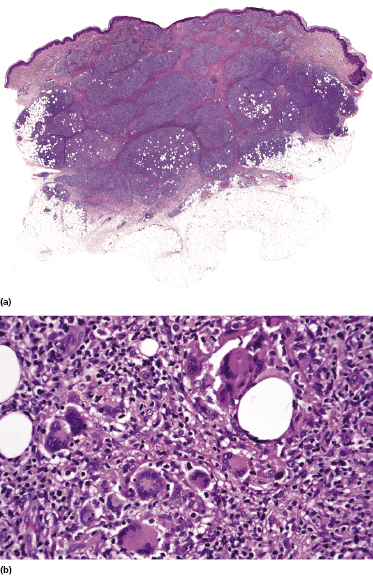

In tumors of mycosis fungoides a dense, nodular, or diffuse infiltrate is found within the entire dermis, usually involving the subcutaneous fat (Fig. 2.39). Epidermotropism may be lost. Flat tumors are characterized histopathologically by dense infiltrates confined to the superficial and mid parts of the dermis (Fig. 2.40). In some cases flat tumors of mycosis fungoides may present with a predominantly interstitial infiltrate (see the section on interstitial mycosis fungoides in this chapter). Prominent involvement of the subcutaneous fat, simulating a subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, may be observed in some cases (Fig. 2.41), as well as very rarely angiocentricity/angiodestruction (Fig. 2.42). It should be underlined that tumors of mycosis fungoides are morphologically indistinguishable from those of other types of primary or secondary cutaneous NK/T-cell lymphoma.

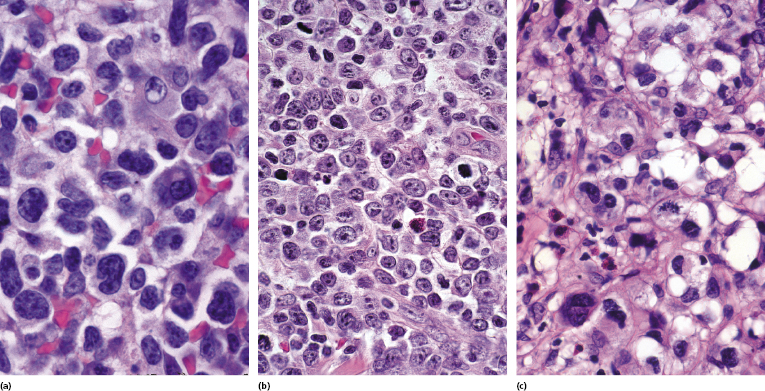

Large Cell Transformation

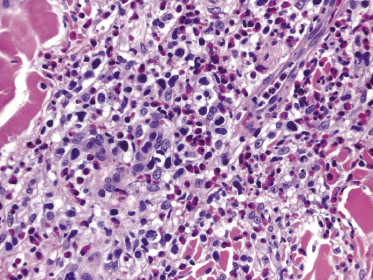

In advanced stages, patients with mycosis fungoides may develop lesions with many large cells (immunoblasts, large pleomorphic cells, or large anaplastic cells) (Fig. 2.43) [54, 55]. Large cell transformation in mycosis fungoides is defined as the presence of large cells exceeding 25% of the infiltrate or of large cells forming microscopic nodules, and has been detected in more than 50% of patients with tumor-stage mycosis fungoides [54]. Clusters of large cells may sometimes be observed in plaques of mycosis fungoides (usually in patients having tumors at other sites of the body), and rarely even in thin patches of the disease (these patients, too, usually also have plaques and tumors of mycosis fungoides at other sites of the body) (see also Teaching case 2.2 in this chapter) (Fig. 2.44).

Tumors with a large cell morphology may or may not express CD30. Negativity for CD30 has been related to a poor prognosis in transformed mycosis fungoides [56]. Spontaneous regression of some lesions and/or CD30 expression by neoplastic cells may suggest the diagnosis of anaplastic large cell lymphoma or lymphomatoid papulosis in these patients, but such a diagnosis should be made only upon compelling evidence in patients with known mycosis fungoides. In this context, most cases of mycosis fungoides with CD30+ large cell transformation are negative for IRF4 translocations, whereas primary cutaneous large cell anaplastic lymphomas are constantly positive [57–59]. In addition, the percentage of CD30+ cells rarely reaches the 75% mark necessary for a diagnosis of anaplastic large cell lymphoma [56, 59a]. Although lymphomatoid papulosis may be associated with mycosis fungoides, the highest degree of caution should be exercised in making this diagnosis when mycosis fungoides precedes the putative lymphomatoid papulosis. In fact, one patient with mycosis fungoides whom we published several years ago as “PUVA-induced lymphomatoid papulosis in mycosis fungoides” [60] turned out to have a CD30+ large cell transformation with bad prognosis, and similar patients have been described as well [61, 62]. Large cell transformation of mycosis fungoides bears a poor prognosis and usually heralds the terminal stage of the disease.

Immunophenotype

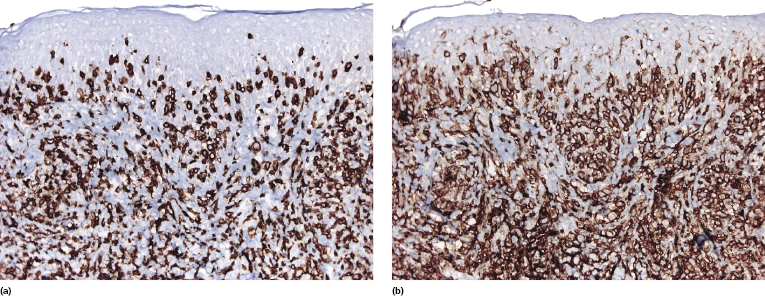

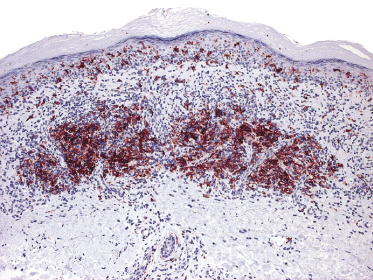

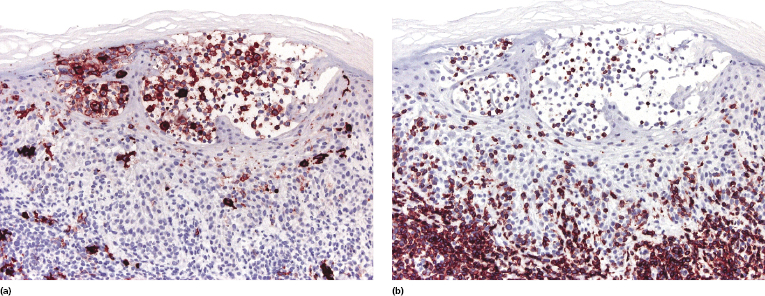

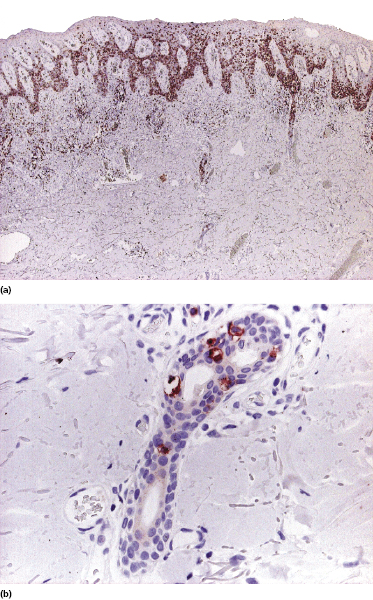

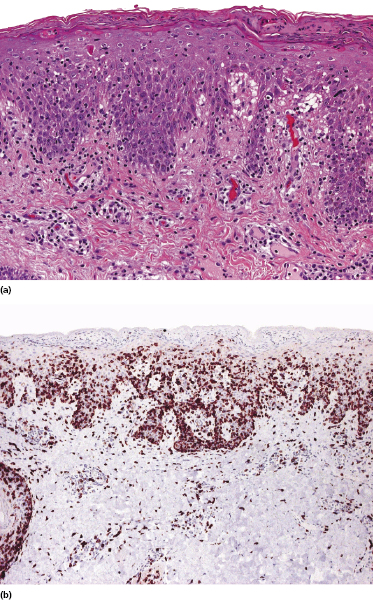

Mycosis fungoides is characterized by an infiltrate of α/β T-helper memory lymphocytes (β F1+, TCR-γ−, CD3+, CD4+, CD5+, CD8−, CD45Ro+, TIA-1−) (Fig. 2.45). Only a minority of cases exhibit a T-cytotoxic (β F1+, TCR-γ−, CD3+, CD4−, CD5+, CD8+, TIA-1+) (Fig. 2.46) or γ/δ (β F1−, TCR-γ+, CD3+, CD4−, CD5+, CD8+, TIA-1+) T-cell phenotype (Fig. 2.47), which show no clinical and/or prognostic differences [63, 64]. In these cases, correlation with the clinical features is crucial, in order to rule out skin involvement by aggressive cytotoxic lymphomas such as cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma or cutaneous γ/δ T-cell lymphoma (see also Chapter 6).

In late stages there may be a (partial) loss of pan-T-cell antigens (CD2, CD3, CD5) and or CD4/CD8 expression (Fig. 2.48). Loss of pan-T-cell markers is a helpful sign for the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides (and of T-cell lymphomas in general), but in my experience it is very rare in early lesions of the disease. Rarely, early mycosis fungoides displays an aberrant CD4+/CD8+ or CD4−/CD8− phenotype. Double negative cases may be positive for PD-1 [65]. Although this molecule is considered as a marker of follicular helper T-cells (TFH), in my opinion and that of others [66] it is not specific for these cells. In general, PD-1 is negative in mycosis fungoides [67], but rare positive cases showing the complete phenotype of TFH cells (PD-1+, Bcl-6+, CXCL13+, CD10+) have been described [68, 69].

Cytotoxic-associated markers such as T-cell intracellular antigen (TIA)-1, granzyme B, and perforin are negative in mycosis fungoides (with the obvious exception of cases with cytotoxic phenotype). In cases that displayed previously a conventional T-helper phenotype, sometimes biopsies of tumor lesions may reveal positivity for TIA-1 [70]. These cases should not be classified as cytotoxic lymphoma, but as tumor-stage mycosis fungoides with a cytotoxic phenotype. Cases with a cytotoxic phenotype may also express CD56 (Fig. 2.49), but CD56-positivity has been observed rarely also in specimens of otherwise conventional CD4+ mycosis fungoides [71].

As already mentioned, in plaque and tumor lesions (and rarely focally in patches, too) neoplastic T-cells may express the CD30 antigen (Fig. 2.50). It has been suggested that a higher expression of CD30 in nontransformed mycosis fungoides is associated with a worse prognosis [72]. On the other hand, CD30-negativity has been linked with a worse prognosis in transformed mycosis fungoides [56]. In my opinion, it is conceptually difficult to conceive of a marker that is associated with both good and bad prognosis depending only on the type of lesion where it is detected (transformed versus nontransformed, respectively), and I think that the prognostic value of CD30 expression (or lack of expression) should be critically considered.

Aberrant expression of the B-cell antigen CD20 by neoplastic T lymphocytes has been observed exceptionally [73] and seems to be more frequent in large cell transformation [73a]. In these cases, negativity for other B-cell markers such as CD79a or PAX-5 and positivity for T-cell markers helps in determining the exact lineage of the cells. Multiple myeloma-1/interferon regulatory factor-4 (MUM1/IRF4), a member of the interferon regulatory factor (IRF) family of transcription factors, is positive in cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders and in CD30+ large cell transformation of mycosis fungoides, but it is otherwise negative in mycosis fungoides.

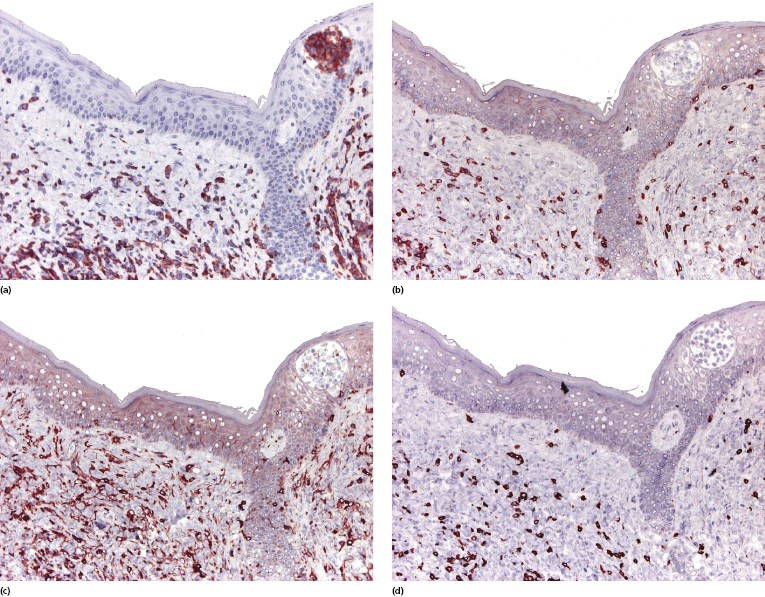

T-regulatory (Treg) cells comprise a T-cell population that can influence other cell types with suppression of the immune response, and that shows mostly a CD4+/CD25+/FOX-P3+ phenotype. They are present in the reactive infiltrate of lesions of early mycosis fungoides but tend to disappear in the tumor stage, and in earlier reports were thought to be related to prognosis. However, studying sequential lesions of patients with mycosis fungoides we could not find a significant difference in the percentage of Treg cells between patch/plaque and tumor stage biopsies, nor any association with prognosis [74]. Additionally, neoplastic lymphocytes with the phenotype of Treg cells can be observed in mycosis fungoides (Fig. 2.51) [74, 75]. It has been suggested that the number of intraepidermal FOX-P3+ cells is higher in inflammatory conditions than in mycosis fungoides [76], but I would exert the greatest caution in using this criterion for the differential diagnosis of early mycosis fungoides.

An increased number of CD1a+ Langerhans cells as well as of other, mostly immature dendritic, cells can be observed in mycosis fungoides, particularly in early lesions, sometimes simulating the picture of a Langerhans cell histiocytosis (Fig. 2.52) [77, 78]. I have come across cases that, besides the typical intraepidermal Darier’s nests (Pautrier’s microabscesses), also revealed intraepidermal collections of Langerhans cells mimicking the histopathologic features of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (Fig. 2.53). These clusters represent most likely a reactive hyperplasia of Langerhans cells. In this context, it should be remembered that the occurrence of clonally related dendritic or histiocytic tumors has been observed rarely in mature B-cell neoplasms (so-called “transdifferentiation” – see Chapter 1), but has never been described in mycosis fungoides. Although “Langerhans cell microabscesses” are considered as a differential diagnostic tool for lymphomatoid contact dermatitis (see Chapter 26), they can be rarely observed in mycosis fungoides as well.

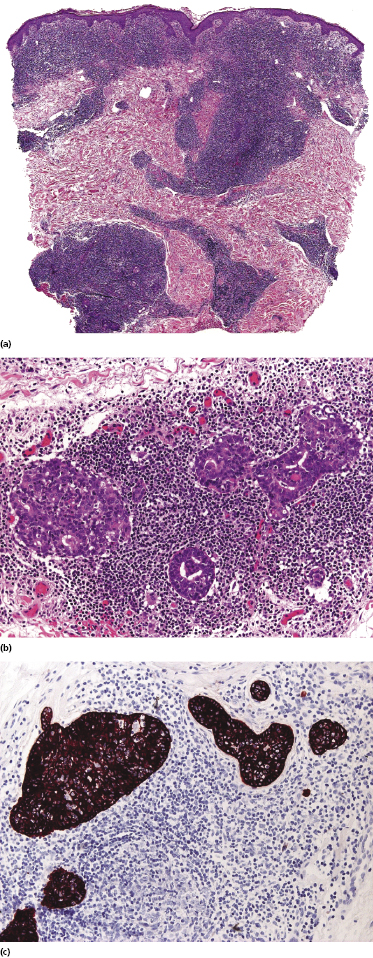

Lesions of mycosis fungoides, particularly in advanced stages, may show a prominent amount of reactive CD20+ B lymphocytes, even forming germinal centers (Fig. 2.54) [79–81]. The B lymphocytes may be prominent and mask the true T-cell nature of the neoplastic infiltrate. These cases should not be misinterpreted as B-cell lymphoma. On the other hand, it should be kept in mind that exceptional cases of composite lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and a primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma within the same lesion) have been observed [43]. B-cell lymphomas composite with mycosis fungoides are mostly cases of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) colonizing the lesions of mycosis fungoides (see Teaching case 19.1 in Chapter 19) [82, 83]. As already mentioned, CD20 may also be expressed aberrantly by neoplastic T lymphocytes, thus underlining the need for complete phenotypic analyses of every case.

Molecular Genetics

There is a considerable body of evidence showing that epigenetic modifications such as aberrant gene methylation and histone deacetylation are involved in the pathogenesis of mycosis fungoides. Dysregulation of the pathway involving the nuclear factor κ-light-chain enhancer of activated B-cells (NF-κB) has been demonstrated in several studies [84, 85]. Downregulation of NFKBIZ has been suggested as the molecular basis for enhanced NF-κB activity [85].

Several studies have addressed early genetic events in mycosis fungoides [86, 87], but results have been sometimes contradictory [88, 89]. In this context, it should be underlined that molecular analysis of early lesions of mycosis fungoides is hindered by the intrinsic difficulties in the identification of neoplastic cells, which are a small minority and may look morphologically and phenotypically identical to reactive lymphocytes. As genetic techniques, especially on routinely fixed specimens, require a certain threshold of tumor DNA, it may be difficult to analyze early lesions of mycosis fungoides where only a few neoplastic cells can be observed. A study on early lesions showed that many genes belonging to pathways associated with inflammation, regulation of apoptosis, and immune activation are upregulated in both early mycosis fungoides and inflammatory disorders [17]. Only a few genes had a discriminatory diagnostic value, and among these TOX (a transcription factor) and PDCD1 (a pro-apoptosis regulator) were considered to be more helpful for identification of early lesions of the disease [17].

Using cDNA microarray analysis, a signature of 27 genes, including oncogenes and other genes involved in the control of apoptosis, has been identified in cases of early- and late-stage mycosis fungoides, and a six-gene prediction model capable of distinguishing mycosis fungoides from inflammatory diseases has been proposed, including FJX1, Hs.127160, STAT4, SYNE-1B, TRAF1, and BIRC3 [90]. In a similar study, consensus clustering revealed the presence of two clusters that tended to include mostly patients with mycosis fungoides in the early stages (Ia and Ib), and of a third cluster limited mostly to patients with more advanced disease [91]. However, the number of cases was relatively small and overlapping data were observed. Using reverse transcription-PCR, 593 genes overexpressed in mycosis fungoides were identified, allowing stratification of the disease in three different prognostic groups [92].

Oncogenes such as p16 and p53 do not show alterations in early lesions, but are often mutated in late (tumor) phases of the disease [93–95]. These results are in keeping with the demonstration that Twist, a transcription factor blocking p53 and inhibiting c-myc-induced apoptosis, is overexpressed only in biopsies from advanced stages [96]. Dysregulated expression of JUNB and JUND has been found in some cases [97] and FAS mutations in others [98]. Recurrent deletions of tumor suppressor genes BCL7A, SMAC/DIABLO, and RHOF have been detected by comparative genome hybridization in cases of early mycosis fungoides [99].

Chromosomal aberrations observed in large cell transformation of mycosis fungoides include alterations of chromosomes 1, 2, 7, 9, 10, 17, and 19, the most common imbalances being gain of chromosome regions 1p36, 1q25-31, 7p22-11.2, 7q21, 9q34, 17q12, 17q24-qter, 19, and loss of 2q36-qter, 9p21, 10p11.2, 10q26, and 17p [34,100]. Loss of heterozygosity but not microsatellite instability is associated with tumor progression [101–103].

Several studies focused on micro RNA (miRNA) expression profiling; miR-92a and miR-155 are upregulated and miR-203 and miR-205 are downregulated in mycosis fungoides as compared to inflammatory disorders [104–106]. Different miRNA expression profiles have also been found in mycosis fungoides when compared with cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma [107], representing a potential tool in the differential diagnosis of CD30+ tumors arising in patients with mycosis fungoides.

A monoclonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor (TCR) genes is commonly found in plaques and tumors of mycosis fungoides. Using a sensitive technique (Biomed-2) the majority (∼80%) of patch lesions also show monoclonality of T lymphocytes. Demonstration of T-cell clonality at the first diagnostic biopsy does not affect the prognosis of patients with early mycosis fungoides [63]. Development of “patient-specific” DNA probes can identify the neoplastic clone also in lesions that are not specific histopathologically [108], and may be a useful method (though not routinely available) for detection of residual disease.

The presence of a monoclonal population of T lymphocytes has been detected in the peripheral blood in patients with early-stage mycosis fungoides. In many of these patients the clone was different from that detected within the skin, but in some cases the same clone was present both in the peripheral blood and in the cutaneous lesions of mycosis fungoides, even after successful treatment and complete clinical remission [26]. The exact diagnostic and prognostic value of molecular genetic analysis of the TCR genes rearrangement within the peripheral blood in patients with early mycosis fungoides is still unclear. Detection of monoclonality within lymph nodes that are not affected clinically and/or histopathologically has been associated with a worse prognosis [109]. The analysis of the rearrangement of TCR genes in the peripheral blood and/or uninvolved lymph nodes is not part of routine investigations in early mycosis fungoides, but the determination of clonality is paramount in lymph nodes showing histopathologically the picture of dermopathic lymphadenopathy.

Histopathologic Differential Diagnosis

The histopathologic diagnosis of early mycosis fungoides may be extremely difficult. In fact, in some instances differentiation from inflammatory skin conditions (e.g., atopic dermatitis, chronic contact dermatitis, etc.) may be impossible on histopathologic grounds alone. In these cases clinical correlation is crucial to make a definitive diagnosis. It should be underlined that in many cases “non-specific” histopathologic features do not allow one to rule out a diagnosis of mycosis fungoides if the clinical presentation is suggestive of the disease. In such cases I describe the histopathologic aspects as “consistent with” the clinical diagnosis, rather than simply issuing a report of “nonspecific chronic dermatitis.” If only biopsies with marked epidermotropism and/or the presence of Darier’s nests (Pautrier’s microabscesses) were to be reported as diagnostic, then the majority of early lesions of mycosis fungoides would be missed on histopathologic grounds. The ISCL proposed a scoring system for diagnosis of early patches of mycosis fungoides [46], but clinicopathologic correlation, integration of all available data, and especially repeated biopsies are crucial.

Immunohistologic features of mycosis fungoides are not distinctive and are similar to those observed in many inflammatory skin conditions. Staining for CD3 or CD4 may help highlighting epidermotropic T lymphocytes, but intraepidermal lymphocytes cannot be considered pathognomonic of mycosis fungoides. It has been suggested that in early stages of mycosis fungoides, in contrast to benign (inflammatory) cutaneous infiltrates of T lymphocytes, there is a loss of expression of the T-cell-associated antigen CD7, but in my opinion this finding is of limited relevance. In addition, T lymphocytes in some cases of benign inflammatory dermatosis can also show partial loss of CD7.

Molecular analysis of TCR genes rearrangement is a further method helpful in the differentiation of mycosis fungoides from benign skin conditions. In particular, detection of the same clone in lesions from different skin sites seems to be highly specific for mycosis fungoides as compared to inflammatory disorders [110]. It must be underlined, however, that several benign dermatoses have been shown to harbor a monoclonal population of T lymphocytes (e.g., lichen planus and lichen sclerosus, among others). In short, absence of clonality should not be considered as a criterion to rule out mycosis fungoides and presence of clonality should not be considered diagnostic for mycosis fungoides. This being the state of affairs, the question may arise as to whether analysis of clonality is an important tool in the diagnosis of early mycosis fungoides. In my opinion, every information, including presence or absence of clonality, is important, but a test that per se allows differentiation of early mycosis fungoides from inflammatory skin disorders does not exist yet, and diagnosis can be achieved only by synthesis of all clinical, histopathologic, phenotypic, and molecular data.

Besides the differential diagnosis with inflammatory (reactive) conditions, mycosis fungoides should be differentiated from other cutaneous lymphomas, particularly Sézary syndrome and cytotoxic NK/T-cell lymphomas (see Chapters 3 and 6).

Clinical and Histopathologic Variants

Mycosis fungoides has been defined as a “dermatologic masquerader” [111, 112], and several clinical and/or histopathologic variants have been described (Table 2.3). It must be underlined that some of these “variants” are peculiar clinical or histopathologic presentations observed only in a few patients, but others are more frequent and may represent a true pitfall in the diagnosis of the disease. Patients with these variants often also show aspects of “conventional” mycosis fungoides at other sites of the body or develop more typical lesions during follow-up. Clinical and/or histopathologic features of a variant of mycosis fungoides may be restricted to a body site or to a time frame.

Table 2.3 Clinicopathologic and phenotypic variants of mycosis fungoides

| Clinical variants with “conventional” histopathological features |

| Acanthosis nigricans-like mycosis fungoides |

| Erythrodermic mycosis fungoides |

| Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides |

| Ichthyosiform mycosis fungoides |

| “Invisible” mycosis fungoides |

| Mycosis fungoides palmaris et plantaris |

| Papular mycosis fungoides |

| Papuloerythroderma Ofuji |

| Parapsoriasis (small-plaque) |

| Perioral dermatitis-like mycosis fungoides |

| Unilesional (solitary) mycosis fungoides |

| Zosteriform mycosis fungoides |

| Clinical variants with peculiar histopathological features |

| Anetodermic mycosis fungoides (mycosis fungoides with secondary anetoderma) (secondary anetoderma may be observed also in generalized follicular mucinosis) |

| Bullous (vesiculobullous) mycosis fungoides |

| Dyshidrotic mycosis fungoides |

| Pilotropic (folliculotropic) mycosis fungoides (with or without follicular mucinosis); Mycosis fungoides with eruptive infundibular cysts and comedones |

| Granulomatous slack skin |

| Hyperpigmented mycosis fungoides |

| Pagetoid reticulosis (Woringer–Kolopp type) |

| Purpuric mycosis fungoides |

| PLEVA-like mycosis fungoides |

| Poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides (poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans) |

| Pustular mycosis fungoides |

| Syringotropic mycosis fungoides |

| Verrucous/hyperkeratotic mycosis fungoides |

| Histopathological variants |

| Granulomatous mycosis fungoides |

| Interstitial mycosis fungoides |

| Mycosis fungoides with large cell transformation |

| Phenotypic variants |

| Cytotoxic mycosis fungoides (CD8+ or g/d+) |

| Mycosis fungoides with T follicular helper (TFH) phenotype |

| Mycosis fungoides with T-regulatory (Treg) phenotype |

Three variants of mycosis fungoides were considered peculiar enough to be listed separately in the WHO–EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas [1] and are mentioned also in the 2008 WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues [3], namely, pilotropic (folliculotropic) mycosis fungoides, localized pagetoid reticulosis (Woringer–Kolopp), and granulomatous slack skin.

In addition to the variants listed in Table 2.3, a plethora of terms has been used in the past for mycosis fungoides (Table 2.4), and unfortunately some of them are still in use today. The use of these terms has brought much confusion to this field and should be discouraged.

| Erythrodermie pityriasique en plaques disseminées |

| Parakeratosis variegata |

| Parapsoriasis en plaques |

| Parapsoriasis lichenoides |

| Parapsoriasis variegata |

| Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans |

| Premycotic erythema |

| Prereticulotic poikiloderma |

| Retiform type of parapsoriasis |

| Xanthoerythroderma perstans |

* Some of these terms are still used today in some centers.

The “Parapsoriases” (Small- and Large-Plaque Parapsoriasis)

In 1902 Louis-Anne-Jean Brocq, a brilliant French dermatologist, introduced a concept and terminology that, in his eyes, were only provisional. He probably never dreamed that over 100 years after his publication experts of cutaneous lymphomas worldwide would still argue on what is parapsoriasis, and what its relationship is to mycosis fungoides. Besides semantic issues (the term parapsoriasis conveys a wrong sense of relationship to psoriasis – but mycosis fungoides, after all, is also a misnomer), the exact nosology of the parapsoriases (small- and large-plaque) is still a matter of discussion. In this context, the term “plaque” is also wrong, as we are referring to lesions that clinically are exclusively patches. Interestingly, already in 1938 Dr Harry Keil, an argute dermatologist practicing in New York City, wrote: “Parapsoriasis en plaques disséminées, parapsoriasis lichenoides of French authors, parakeratosis variegata, and the retiform type of parapsoriasis with their evolution into poikiloderma probably represent different phases of a single disease, which invariably progresses to mycosis fungoides. (…) The nomenclature of parapsoriasis, mycosis fungoides and poikiloderma vascolare atrophicans should be revised in the light of collected data.”

In my opinion, there is no doubt that large-plaque parapsoriasis belongs to the clinical spectrum of mycosis fungoides and cannot (and should not) be distinguished from other early manifestations of the disease (Fig. 2.55). Thus, in what follows I will only concentrate on small-plaque parapsoriasis, as this is a much more slippery subject. At the beginning, however, it should be underlined that distinction of “small-plaque” from “large-plaque” parapsoriasis is a matter of discussion, too, as (i) it only relies on the size of lesions (and size was never defined precisely) and (ii) often both small and large lesions are present in one and the same patient. Besides, it is well known that small patches of disease are common in patients with otherwise “conventional” mycosis fungoides. I refer to small-plaque parapsoriasis as a disease presenting exclusively with small patches (not larger than a few centimeters). Numbers defining exactly the size of the patches would only add a false sense of precision that in my opinion does not exist.

Patients presenting only with small, sometimes “digitated” patches, typically located on the trunk and upper extremities (Fig. 2.56), are variously diagnosed as “digitate” dermatosis, chronic superficial scaly dermatitis, small-plaque parapsoriasis, or mycosis fungoides. Molecular genetic techniques reveals that in some of these lesions a monoclonal population of T lymphocytes can be found. As already mentioned, the exact relationship between small-plaque parapsoriasis and mycosis fungoides is still a matter of debate: some think that they represent one and the same disease, whereas others maintain that they are completely unrelated [113, 114]. In Graz we have observed patients with small patches of “parapsoriasis en plaques” who on follow-up developed typical plaques and tumors of mycosis fungoides, leading us to conclude that small-plaque parapsoriasis represents an early manifestation of the disease. A similar observation has been reported by Väkevä and co-workers, who observed that 10% of their patients with small-plaque parapsoriasis developed mycosis fungoides during the course of the disease [115], and by Belousova and co-workers [116].

In the context of the discussion on small-plaque parapsoriasis, it should be noted that the boundary between “overt” cancer, “early” cancer, and “precursor” of cancer is getting more and more blurred by new molecular insights (see also Chapter 1). In this context, “small-plaque parapsoriasis” is as good (or as bad) a term as any other used in the field of “early” or “pre-malignant” lymphoproliferative disorders (e.g., monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis, etc.), and can be used in order to avoid a diagnosis of “mycosis fungoides” for patients who will likely experience no serious problems from the disease. Regardless of the academic discussion, it is important to underline that patients with small-plaque parapsoriasis should not be treated aggressively, as progression of the disease is rare and, when it happens, takes place only after very long periods of time.

Once again, it must be clearly stated that “large-plaque parapsoriasis” represents one of the most typical early manifestations of “conventional” mycosis fungoides.

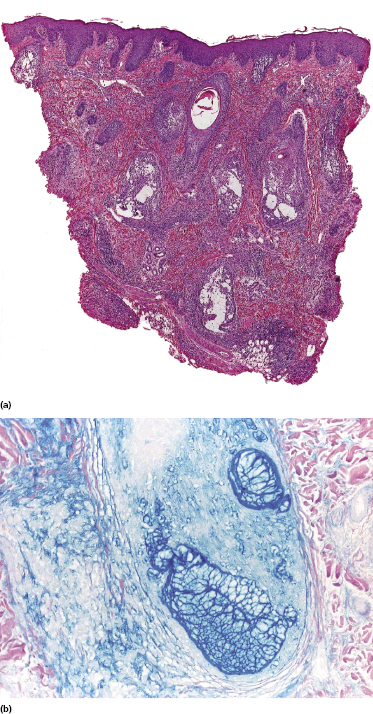

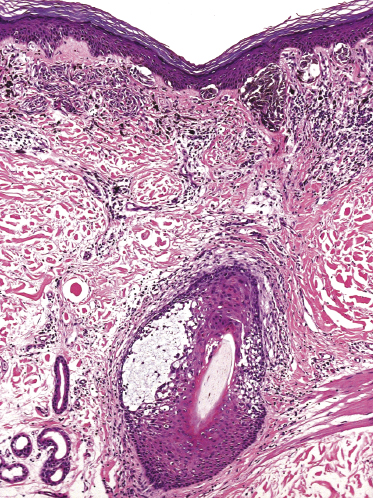

Pilotropic (Folliculotropic) Mycosis Fungoides (with or Without Follicular Mucinosis) and Relationship with So-Called “Benign” Follicular Mucinosis

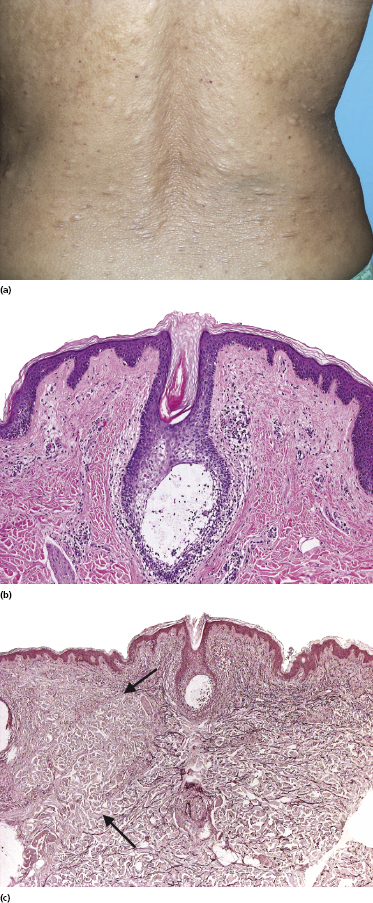

Some patients with mycosis fungoides present with follicular papules and plaques characterized histopathologically by abundant deposits of mucin within hair follicles that are surrounded and infiltrated by T lymphocytes (Figs 2.57 and 2.58) [117]. Clinically, sometimes only small areas of patchy alopecia are visible (Fig. 2.59). At body sites with only vellus hairs, lesions may be very subtle, and it may be difficult to appreciate the extent of the disease (Fig. 2.60). Tiny keratotic spines may protrude from affected follicles and confer on the lesion some resemblance to lichen spinulosus (Fig. 2.61). In several cases the prominent follicular distribution of the lesions without involvement of the interfollicular epidermis produces a characteristic appearance of “agminated” lesions (Fig. 2.62). Rarely, pilotropic mycosis fungoides presents with solitary lesions [118].

Histopathologically, the hair follicles are infiltrated by neoplastic lymphocytes (“pilotropism”) (Fig. 2.63). The number of intraepithelial lymphocytes is variable. Large deposition of mucin may disrupt the follicle and make it more difficult to appreciate the lymphocytes. In later lesions, a prominent granulomatous reaction may rarely replace the entire follicle (Fig. 2.64). The onset of pustules, mimicking an inflammatory condition, is much more frequent in pilotropic mycosis fungoides than in other variants of the disease (Fig. 2.65). The epidermis is usually spared, but in rare cases a conventional picture of epidermotropic mycosis fungoides may be observed between affected follicles (Fig. 2.66). Eosinophils are present as a rule in cases characterized by deposition of mucin and may occasionally be a prominent feature (Fig. 2.67). Itching is severe and represents a major problem in this variant of mycosis fungoides, and may be nonresponsive to standard treatments. Prurigo-like lesions caused by scratching may complicate the clinical picture and lead to the erroneous diagnosis of atopic or other eczematous dermatitis (Fig. 2.68).

Deposition of mucin is found only in a proportion of cases of pilotropic mycosis fungoides (Fig. 2.69). In some patients follicular mucinosis may be observed in one biopsy but not in other specimens, confirming that pilotropic mycosis fungoides represents a spectrum characterized by prominent involvement of the hair follicles with or without mucin deposition [119, 120]. When present, deposition of mucin is usually restricted to the hair follicle, but I have observed cases with intraepidermal deposition as well (Fig. 2.70). Particularly in advanced stages, the typical histopathologic features of pilotropic mycosis fungoides tend to disappear and conventional tumors may be observed.

As already mentioned, alopecia due to destruction of the follicles is common (so-called alopecia mucinosa), either generalized or localized. The pattern of alopecia in mycosis fungoides is often distinctive and is characterized by irregular areas of hair loss, patchy erythema, and follicular papules and/or comedones (Fig. 2.71). In some patients alopecia areata-like lesions or even alopecia universalis may be observed [121]. Sometimes alopecia can be present in patients who do not have other lesions of follicular mycosis fungoides, but it is most prominent in the pilotropic variant of the disease [121].

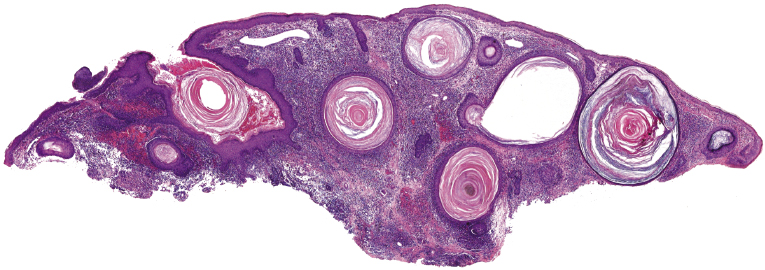

In patients with marked involvement of the hair follicles, with or without deposition of mucin, a localized or rarely widespread eruption of small infundibular cysts and/or comedones infiltrated by neoplastic T lymphocytes can be observed (“mycosis fungoides with eruptive cysts and comedones”) (Figs 2.72, 2.73, and 2.74) [122]. The clinical picture is similar to that observed in so-called “milia en plaques”, a condition that besides mycosis fungoides can be associated to several inflammatory disorders. Prominent involvement of the hair follicles with follicular hyperplasia may lead to the formation of elevated lesions, clinically resembling tumors of the disease, even in the absence of true neoplastic tumors (“pseudotumoral mycosis fungoides”) [123].

There is no consensus on the exact nosology of so-called “idiopathic generalized follicular mucinosis” [117], and some authors do not believe that it represents a manifestation of mycosis fungoides. The term “pilotropic T-cell dyscrasia” has been introduced for this condition [124]. However, cases of “idiopathic generalized follicular mucinosis” with progression to advanced mycosis fungoides and death have been well documented (Fig. 2.75) [117]. I have observed patients with clear-cut pilotropic mycosis fungoides who entered clinical remission after conventional treatments, and who subsequently relapsed with skin lesions showing clinical and histopathologic features of “idiopathic” follicular mucinosis. Interestingly, generalized follicular mucinosis may rarely present with hypopigmented lesions, indistinguishable from hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (Fig. 2.76). In my opinion, “idiopathic generalized follicular mucinosis” represents a variant of mycosis fungoides and association with the disease has been observed even in children [125, 126]. The discussion is not only academic, however, as some authors reported a worse prognosis in patients with pilotropic mycosis fungoides as compared to those with “conventional” variants of the disease [127–130]. However, patients with idiopathic generalized follicular mucinosis were not included in these studies, thus introducing a selection bias. Other reports revealed a prognosis of pilotropic mycosis fungoides similar to that of the conventional variant of the disease [131].

The nosology of “benign” localized follicular mucinosis is unclear. Patients are usually children or young adults, presenting with a single infiltrated patch on the face and alopecia in the affected region (Fig. 2.77). Although “benign” localized follicular mucinosis may be compared conceptually to a “solitary” variant of mycosis fungoides with good prognosis, I have never observed progression to advanced stages of the disease. On the other hand, the clinicopathologic features are indistinguishable from those of pilotropic mycosis fungoides and monoclonality of T lymphocytes can be demonstrated in about half of the cases [117]. It has been suggested that current diagnostic criteria for early mycosis fungoides should not be applied to children with alopecia mucinosa [132], but I would agree only for those presenting with solitary lesions of the disease, as pediatric patients with generalized involvement of the skin in my opinion have mycosis fungoides. For practical purposes, I do not use the term “mycosis fungoides” for cases characterized by solitary lesions in children and adolescents. Management should be conservative and spontaneous resolution may occur.

The last variant of follicular mucinosis, the so-called acneiform type, is very rare. It is characterized by follicular, erythematous papules on the head and neck area and on the upper trunk (Fig. 2.78). In this type, too, the relationship to mycosis fungoides is unclear, but a follow-up study showed an invariably benign course [132a]. I have seen only a few patients, and none of them developed clear-cut mycosis fungoides. However, “acneiform” follicular lesions have been described in patients with mycosis fungoides [127], and a monoclonal T-cell population may be observed in the infiltrate [133].

Finally, it should be mentioned that deposition of mucin within the hair follicle is not synonymous with alopecia mucinosa/follicular mucinosis, and it may be an incidental finding in biopsy specimens of different conditions (Fig. 2.79) [133a].

Syringotropic Mycosis Fungoides

Some patients present with unusual lesions consisting of dense lymphoid infiltrates located mainly around hyperplastic eccrine glands and coils, often with syringometaplasia (Fig. 2.80) [134, 135]. The hair follicles are usually involved as well and are surrounded by dense lymphoid infiltrates with pilotropism. A concomitant band-like infiltrate in the papillary dermis is observed in the majority of the specimens. Particularly in cases without band-like infiltrate, however, the histopathologic diagnosis may be very difficult (Fig. 2.81). Clinically, in many cases distinction from pilotropic mycosis fungoides is not possible, and lesions may show a similar follicular plugging with agminated arrangement (Figs 2.82 and 2.83). In fact, syringotropic and pilotropic mycosis fungoides are closely related and should probably be regarded as a unique type of “adnexotropic” mycosis fungoides. Lesions may be generalized or solitary. Palms and soles are involved more commonly than in other variants of the disease (Fig. 2.84). In some cases, conventional patches of mycosis fungoides are present at other body sites.

The term “syringolymphoid hyperplasia with alopecia” has been used in the past to refer to these cases, but the relationship to mycosis fungoides has been well recognized [134].

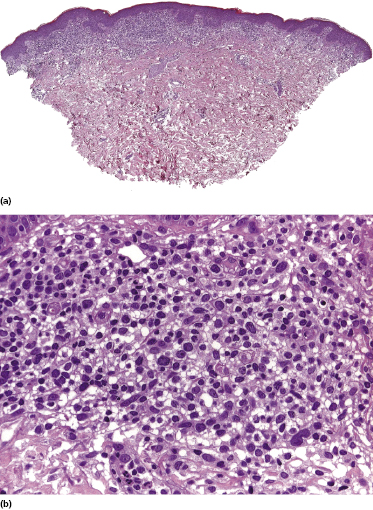

Localized Pagetoid Reticulosis (Woringer–Kolopp Type)

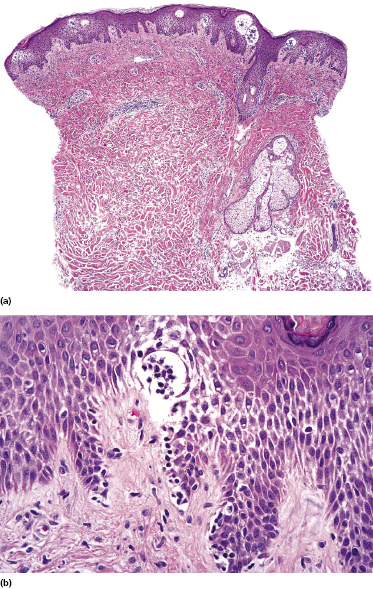

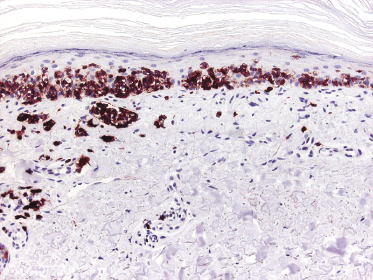

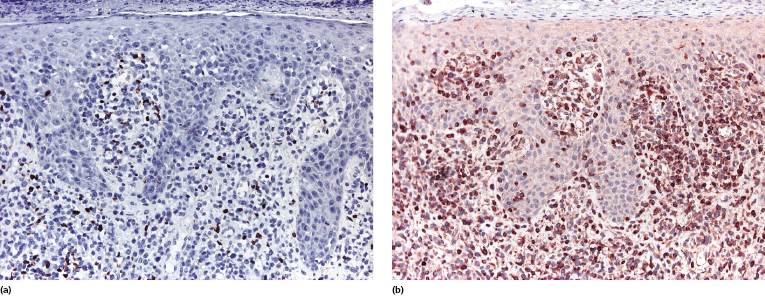

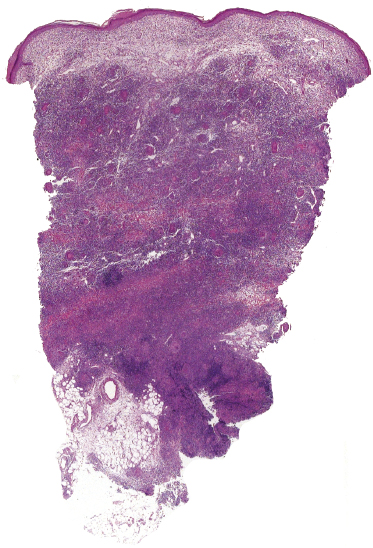

Localized pagetoid reticulosis is a variant of mycosis fungoides presenting with psoriasiform, scaly erythematous patches or plaques, usually located on the extremities (Fig. 2.85). The lesions are either solitary or localized to one acral site. The clinical presentation can be deceptive, simulating that of benign conditions such as warts or eczematous dermatitis (Fig. 2.86). The histologic picture shows a markedly hyperplastic epidermis with striking epidermotropism of medium-sized pleomorphic lymphocytes (Fig. 2.87). Neoplastic lymphocytes usually have a T-cytotoxic phenotype (Fig. 2.88a), but a helper phenotype or double negativity for both CD4 and CD8 have been reported [136]. The lymphocytes may show a tropism for adnexal structures and grow along the eccrine coils (Fig. 2.88b), thus cautioning against superficial treatment modalities.

The term “pagetoid reticulosis” should be restricted to solitary or localized lesions only (Woringer–Kolopp type). Most patients presenting with the “generalized” form of pagetoid reticulosis (Ketron–Goodman type) have one of the cutaneous aggressive cytotoxic NK/T-cell lymphomas (cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma, cutaneous γ/δ T-cell lymphoma, extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type) (see Chapter 6).

It should be emphasized that a histopathologic picture characterized by markedly hyperplastic epidermis with striking epidermotropism of innumerable T lymphocytes is not restricted to pagetoid reticulosis or aggressive cytotoxic NK/T-cell lymphomas: other lymphomas may rarely present with similar features and a definitive diagnosis should be made only upon compelling clinicopathologic evidence and after complete phenotypic and genotypic studies [137]. Lymphomatoid papulosis, type D may be indistinguishable from pagetoid reticulosis histopathologically, but shows the typical waxing and waning course clinically, and usually does not arise on acral sites (see Chapter 4). Presence of intraepidermal CD30+ neoplastic cells in “pagetoid reticulosis” should raise suspicion of such a variant of lymphomatoid papulosis; a precise classification of these cases can be achieved only upon clinicopathologic correlation.

The prognosis of patients with solitary pagetoid reticulosis is excellent and involvement of internal organs has never been observed. Development of conventional mycosis fungoides has been documented in a few patients. The treatment of choice is surgical excision or local radiotherapy. Other skin-directed therapies may be used for more extensive lesions, including topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, PUVA, and narrow-band UV-B irradiation [138], but superficial treatment modalities may be ineffective in cases showing deeper extension along the adnexal structures (see Fig. 2.88).

Unilesional (“Solitary”) Mycosis Fungoides

Besides localized pagetoid reticulosis, a solitary variant of mycosis fungoides with clinicopathologic features similar to “common” mycosis fungoides has been described [139–141]. The literature about this subject is confusing, as in the past disparate cases were lumped together in this category, including pagetoid reticulosis and “mycosis fungoides en tumeur d’emblée” among others. In addition, many of the cases reported in the literature probably represent in truth examples of lichenoid keratosis or other pseudolymphomas (including some of the cases published by our group – see the section on solitary idiopathic B/T-cell pseudolymphoma in Chapter 26) [139], but I have rarely observed patients with solitary lesions of genuine mycosis fungoides (Fig. 2.89). Histopathological features are identical to those of conventional mycosis fungoides. Rarely, large cell transformation may be observed in solitary lesions, representing a sign of disease’s progression (see Teaching case 2.2 in this chapter).

It is yet unclear whether solitary mycosis fungoides has a better prognosis [142], but in some instances development of generalized lesions of the disease has been observed over time [143]. As in other variants of the disease, the presence of large cell transformation should be regarded as a bad prognostic sign.

Granulomatous Mycosis Fungoides

Granulomatous mycosis fungoides is an unusual histologic variant of the disease described first by Ackerman and Flaxman in 1970, who reported a patient with tumor-stage mycosis fungoides with histiocytic giant cells scattered within the dermal infiltrate [144].

Granulomatous lesions may either precede, be concomitant with, or follow “classic” mycosis fungoides; they can be observed in patches, plaques, and tumors of the disease, and in some cases even within affected lymph nodes [145]. Clinically there may be irregular areas of induration (Fig. 2.90), but in most cases the clinical aspect does not betray the presence of granulomas histopathologically. In my experience a granulomatous reaction is observed mostly in tumors of mycosis fungoides, and sometimes may be secondary to treatment. Granulomas can also be observed in the context of pilotropic mycosis fungoides, due to destruction of hair follicles (see the section on pilotropic mycosis fungoides in this chapter). Especially if the first manifestation of the disease shows prominent granulomatous features, the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides may be missed, and the histopathologic picture may be misinterpreted as that of a “granulomatous dermatitis.” Epidermotropism is a helpful clue (Fig. 2.91), but it is often minimal or missing in granulomatous tumors (Fig. 2.92).

Histopathologically, granulomatous mycosis fungoides may also be difficult or even impossible to distinguish from other cutaneous T-cell lymphomas with granulomatous features (e.g., CD4+ small/medium T-cell lymphoma) [146], and clinicopathologic correlation is crucial for the diagnosis.

Granulomatous mycosis fungoides seems to have a worse prognosis than that of conventional variants of the disease, and patients have a higher risk of developing a second lymphoma [147]. On the other hand, the amount of the granulomatous reaction is often variable in different biopsies from a single patient, suggesting that the term “granulomatous mycosis fungoides” should be used as a description of histopathologic specimens, and not for classifying the disease in a given patient. It is also important to realize that differentiation of “conventional” granulomatous mycosis fungoides from granulomatous slack skin cannot be achieved on histopathologic grounds only and that correlation with the clinical picture is crucial for a precise classification [148].

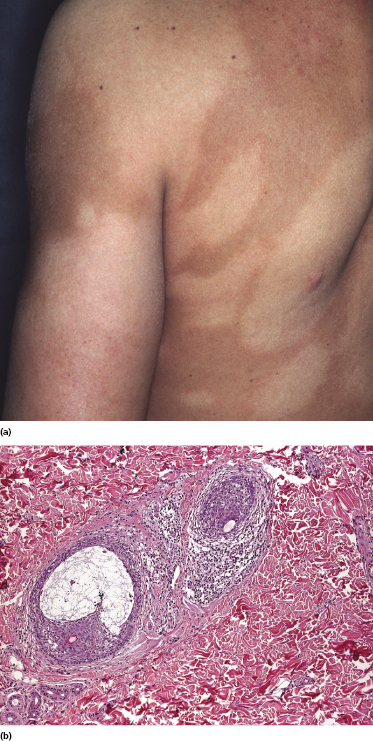

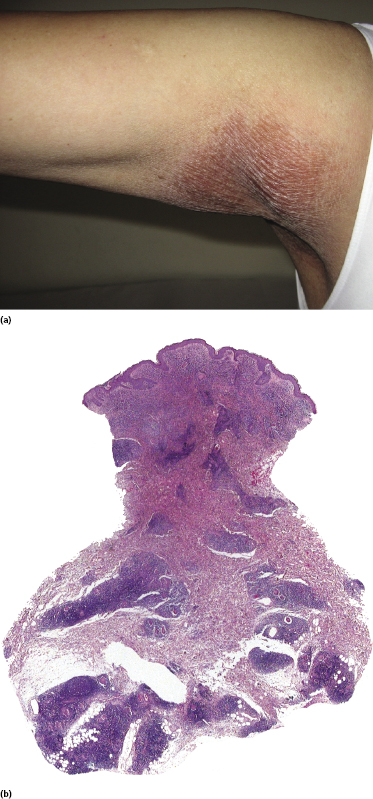

Granulomatous Slack Skin

A rare variant of granulomatous mycosis fungoides is represented by granulomatous slack skin, which is characterized clinically by the occurrence of bulky, pendulous skinfolds, usually located in flexural areas (Fig. 2.93) [149–151]. Granulomatous slack skin is considered as a specific manifestation of mycosis fungoides in most cases and is included as a variant of mycosis fungoides in the WHO classification [3]. Association with other lymphomas, including Hodgkin lymphoma, has been reported. In most of these cases, on the other hand, granulomatous slack skin probably represented a manifestation of mycosis fungoides associated with a second lymphoma, rather than a clinicopathologic variant of the other lymphoma.

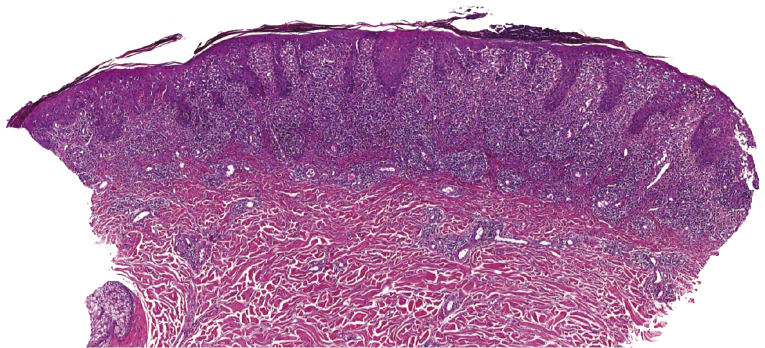

The granulomatous infiltrate in granulomatous slack skin is usually diffuse and involves the subcutaneous tissues, in contrast to the patchy, dermal granulomas observed in “conventional” granulomatous mycosis fungoides (Fig. 2.94), but differentiation between the two variants may not be possible on histopathological grounds alone. Giant cells with many nuclei are a common finding (Fig. 2.95). Elastophagocytosis is also typically present. The same rearrangement of T-cells has been observed in skin and nodal lesions in one patient [152], and a t(3;9)(q12;p24) has been detected in another case [153].

As already mentioned, a diagnosis of granulomatous slack skin can only be made when the typical clinical presentation is observed, as histopathological differentiation from “conventional” granulomatous mycosis fungoides is not possible [148]. On the other hand, in some patients lesions located at typical sites of granulomatous slack skin (axillae, groins), but that do not show bulky, pendulous skin folds, may be considered as early manifestations of the disease if the characteristic histopathologic features described above are present (Fig. 2.96). Whether these patients, if untreated, progress to overt granulomatous slack skin is unclear.

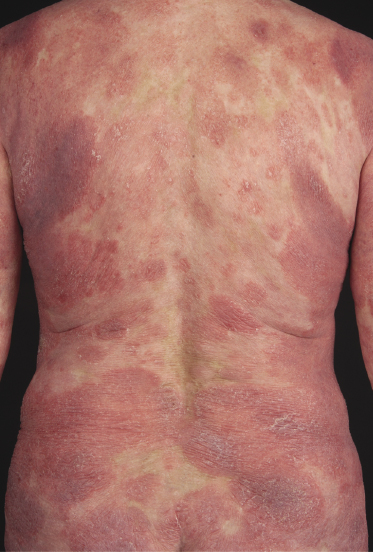

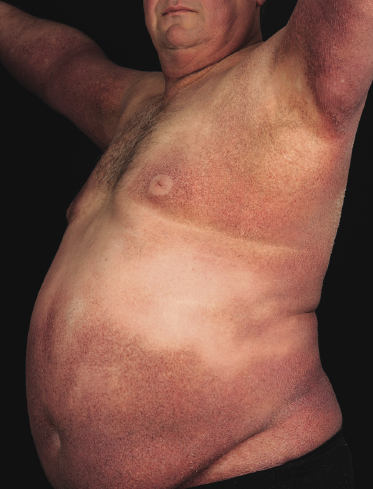

Erythrodermic Mycosis Fungoides

Patients with mycosis fungoides may develop erythroderma during the course of their disease (Fig. 2.97). Rarely, swelling of the lymph nodes and presence of circulating neoplastic cells (“Sézary cells”) are observed as well, thus showing overlap of clinical features with Sézary syndrome. The histopathologic and phenotypic features are identical to those of conventional mycosis fungoides. After successful treatment patients may relapse with conventional patches, plaques or tumors of mycosis fungoides or with new flares of erythroderma. These cases should not be classified as Sézary syndrome but as erythrodermic mycosis fungoides, and the diagnosis of Sézary syndrome should be reserved to those patients presenting with the typical features of this disease from the outset [1, 3]. In fact, a strong support to the distinction of mycosis fungoides from Sézary syndrome has been provided by phenotypic and genetic analyses that showed major differences between the two diseases [34–36]. Precise history taking is crucial for proper diagnosis, and often only evidence of previous mycosis fungoides allows classification of these cases as erythrodermic mycosis fungoides.

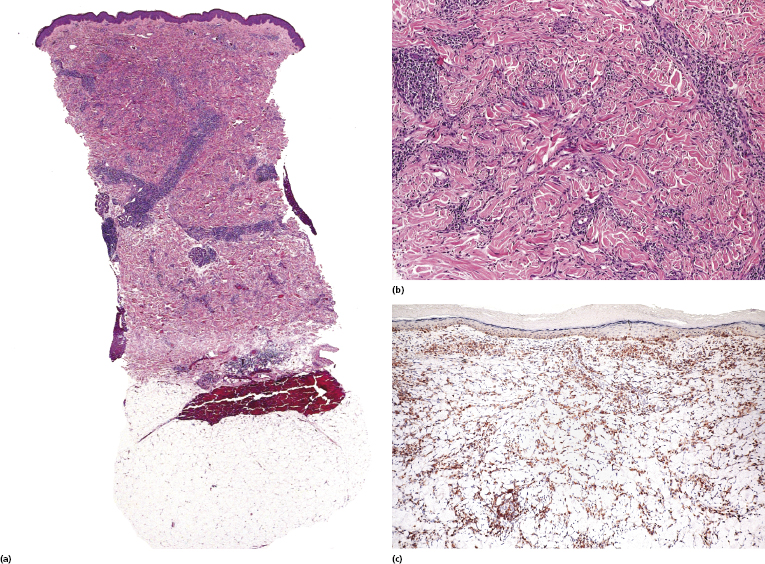

Interstitial Mycosis Fungoides

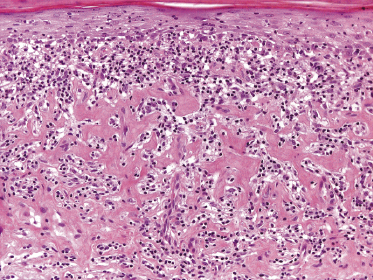

Interstitial mycosis fungoides is a variant of the disease that does not have a characteristic clinical presentation, but shows histopathologically a pattern that may be misinterpreted as that of an inflammatory dermatosis (particularly interstitial granuloma annulare and inflammatory stage of localized scleroderma) [154]. It is observed usually in flat tumors of mycosis fungoides.

Epidermotropism and a band-like pattern may be missing, and histology shows dermal infiltrates of lymphocytes dissecting the collagen bundles (Fig. 2.98a and b). Immunohistology confirms that most interstitial cells are T lymphocytes, which is a helpful clue for the differential diagnosis with interstitial inflammatory dermatoses (Fig. 2.98c). “Free floating” collagen fibers surrounded by neoplastic lymphocytes have been observed in interstitial mycosis fungoides but not in granuloma annulare or morphea [155]. In this context, it should be remembered that granuloma annulare may rarely present with pseudolymphomatous infiltrates, thus complicating the differential diagnosis between the two diseases [156], and that a rare case of genuine granuloma annulare in a patient with mycosis fungoides has been reported [157].

Poikilodermatous Mycosis Fungoides (Poikiloderma Vasculare Atrophicans)

Poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides is one of the most common clinicopathologic variants of the disease. It is characterized clinically by atrophic, red-brown macules and patches with prominent teleangectasia (Figs 2.99 and 2.100). Sites of predilection are the breast and buttocks, but lesions may be generalized. Sometimes a “retiform” pattern can be observed (formerly referred to as “parakeratosis variegata”). Histology reveals an atrophic epidermis with loss of rete ridges, an interface dermatitis with a superficial, band-like infiltrate of lymphocytes with epidermotropism, and a thickened papillary dermis (Fig. 2.101). Necrotic keratinocytes and pigment incontinence may be a prominent finding. Dilated capillaries are present within the superficial dermis. This variant has also been referred to as the “lichenoid” type of mycosis fungoides, and in some cases distinction from pigmented atrophic lichen planus may be impossible without correlation with the clinical picture.

A cytotoxic phenotype seems to be common in poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides [158]. Recent data point to a better prognosis of poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides as compared to other variants of the disease [24].

Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

Patients with mycosis fungoides may develop hypopigmented patches and plaques (Fig. 2.102). These lesions may be misinterpreted clinically as those of pityriasis versicolor, pityriasis alba, or vitiligo. Histology reveals typical features of mycosis fungoides. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides is observed more frequently in dark-skinned individuals and is one of the most frequent variants seen in children [159, 160]. Repigmentation usually takes place after successful treatment of the lesions.

Although hypopigmented lesions may be the sole manifestation of mycosis fungoides, in many cases, especially in Caucasians, careful examination of the patients will allow the presence of erythematous lesions to be detected as well (Fig. 2.103). Interestingly, patients with hypopigmented mycosis fungoides tend to develop more hypopigmented lesions during the course of the disease, suggesting that this is indeed an unusual variant of mycosis fungoides.

A predominant CD8+ phenotype has been described in patients with hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, possibly underlying some pathogenetic similarities to vitiligo [159]. However, a CD4+ phenotype can be observed as well [160], and most cases of mycosis fungoides that are positive for CD8 are not hypopigmented clinically. It should be underlined that differential diagnosis of hypopigmented mycosis fungoides from its simulators, including particularly atopic dermatitis and the inflammatory stages of vitiligo, may be extremely difficult, and that at least some of the cases published in the literature may not represent genuine examples of hypopigmented mycosis fungoides. In my experience this problem is particularly evident in children, and sometimes only follow-up data provide a precise diagnosis (see also Chapter 26).

It is interesting to note that hypopigmented lesions have been described in so-called parapsoriasis en plaques [161] and that an identical clinical presentation may be observed also in “idiopathic generalized follicular mucinosis” (see Fig. 2.76), again suggesting that these are variants of mycosis fungoides.

Hyperpigmented Mycosis Fungoides

Rarely, the clinical picture of mycosis fungoides may be characterized by markedly hyperpigmented lesions, corresponding histopathologically to the presence of pigment incontinence and abundant melanophages in the papillary dermis (Figs 2.104 and 2.105). The phenotype of these lesions is more often cytotoxic than helper [162], possibly explaining the damage at the dermo-epidermal junction and subsequent pigment incontinence. On the other hand, it should be underlined that most cases of mycosis fungoides with cytotoxic phenotype do not present with hyperpigmented lesions.

Generalized hyperpigmented lesions covering the entire body have been described as “melanoerythroderma”, and are seen more frequently in patients with Sézary syndrome.

Purpuric Mycosis Fungoides

In some patients, lesions of mycosis fungoides are characterized clinically by a purpuric hue (Fig. 2.106) and histopathologically by the presence of many extravasated erythrocytes and siderophages (Fig. 2.107).

The differential diagnosis of purpuric mycosis fungoides from lichenoid purpura and lichen aureus can be difficult on histopathologic grounds, and correlation with the clinical features is crucial (see also Chapter 26). The distinction has been rendered even more difficult by the introduction of the term “atypical pigmented purpura” and by the suggestion of a possible relationship between some purpuric dermatoses and mycosis fungoides [163, 164]. Rare patients with “pigmented purpura” progressing to mycosis fungoides [165, 166] probably had purpuric mycosis fungoides from the outset. In this context, it should be emphasized that lichen aureus and lichenoid purpura are wholly benign disorders that should be clearly differentiated from mycosis fungoides.

Papular Mycosis Fungoides

In some patients with mycosis fungoides, small papules represent the predominant morphologic expression of the disease, and small and/or large patches are absent (Fig. 2.108) [167, 168]. The papules are not centered on the hair follicles, and these last are not involved histopathologically. Histopathologic examination reveals conventional features of mycosis fungoides, but the infiltrate is restricted to a part only of the biopsy specimen (Fig. 2.109). The absence of typical manifestations of the disease renders the clinical diagnosis very difficult. Moreover, differentiation from type B lymphomatoid papulosis can only be achieved by short-term follow-up of the patients, as the histopathologic features may be indistinguishable (CD30, however, is usually negative in papular mycosis fungoides). In fact, papular lesions of mycosis fungoides do not show the spontaneous regression typical of type B lymphomatoid papulosis.

Although we initially suggested that papular mycosis fungoides had the same prognosis as other variants of early mycosis fungoides [167], since the original publication I have observed patients who progressed to erythroderma or tumor stage within relatively short periods of time; thus great caution should be exerted in the management of these cases.

Bullous (Vesiculobullous) and Dyshidrotic Mycosis Fungoides

Some patients with mycosis fungoides present with vesicular or bullous lesions, these last usually associated with large, superficial erosions (Fig. 2.110). Histologic examination reveals bullous lesions characterized either by cleavage at the dermoepidermal junction or by confluence of intraepidermal vesicles (Figs 2.111 and 2.112). Sometimes the bullae are not visible on histopathologic specimens and only superficial erosions are present (see Teaching case 2.1 in this chapter). A “dyshidrotic” variant of the disease located on the palms and soles may also present with vesicular lesions (Figs 2.112 to 2.114). Typical features of mycosis fungoides are commonly present near to the vesicular and bullous ones, or at other sites of the body.

The reason(s) for the formation of vesicular and bullous lesions is unclear. Some cases may be due to pre-existent dyshidrotic or vesicular dermatitis and subsequent colonization by neoplastic cells. In other patients a direct cytotoxic effect may be responsible for the detachment of the epidermis from the dermis or pronounced spongiosis may lead to vesiculation, and eventually larger blisters may develop due to confluence of vesicles. Neoplastic cells may also induce directly and/or indirectly degeneration of collagen bundles and the blistering [169]. In some patients, onset of bullous lesions has been related to the use of interferon-α. Rarely, coexistence of mycosis fungoides and an autoimmune bullous disorder may be the reason for this peculiar clinical presentation.

Eczema herpeticatum developing on the background of bullous mycosis fungoides has been described [170].

Anetodermic Mycosis Fungoides

Two patients with secondary anetoderma developing on pre-existing lesions of mycosis fungoides have been described [171]. Some of the lesions depicted in this study resembled small tumors clinically, but represented probably just secondary anetodermic changes in flat lesions of mycosis fungoides, thus being a potential pitfall in clinical evaluation of the patients. Although loss of elastic fibers is observed also in granulomatous slack skin, anetoderma secondary to mycosis fungoides has completely different clinical and histopathologic features, and there is no relationship between these two variants of the disease.