Cutaneous Manifestations of B-cell Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) represents the most frequent type of chronic lymphocytic leukemia [1]. In patients affected by the disease cutaneous lesions are common, representing in most instances nonspecific manifestations related to the impaired immune competence or to the ingestion of drugs. In some cases, however, neoplastic B lymphocytes are found within the skin [2]. Such lesions are referred to as specific cutaneous manifestations of B-CLL or as “leukemia cutis.” It must be remembered that under the same term of “leukemia cutis” specific cutaneous manifestations of other types of leukemia, particularly myelogenous leukemia, have also been described. In contrast to cutaneous involvement by myeloid leukemia, which sometimes is observed before the diagnosis of leukemia is established in the bone marrow and/or blood (“aleukemic” leukemia cutis – see Chapter 20), specific cutaneous manifestations of B-CLL are usually concomitant to the first diagnosis or arise during the course of the disease, and only rarely predate the diagnosis [3].

Specific infiltrates of B-CLL have been frequently observed at the site of cutaneous inflammation due to different causes, showing that neoplastic cells retain at least in part the capability to answer chemotactic stimuli and to migrate to tissues where an immune response is being mounted [4–7].

A peculiar condition known as “exaggerated arthropod bite-like reaction” has been described in patients with various hematological disorders [8]. Hypersensitivity to mosquito bites is a well-known feature of hydroa-like lymphoma and of some forms of natural killer (NK)-cell lymphoma, but has been observed also in B-CLL and in other types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In many of these cases an insect bite is not recalled by the patients, yet clinicopathologic features are those of an arthropod assault. When these lesions arise in the context of a B-CLL, neoplastic cells are sometimes found within the biopsy specimen admixed with large numbers of eosinophils. The lesions are unrelated to laboratory findings, disease course, therapy, or prognosis, and usually resolve within a few weeks.

Clinical Features

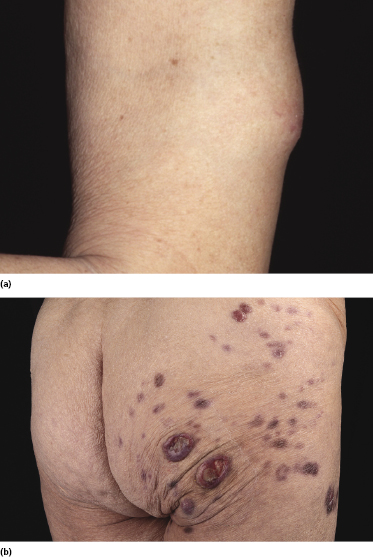

Clinically, patients with specific cutaneous manifestations of B-CLL present with localized or generalized erythematous papules, plaques, or tumors [2, 9–11]. Ulceration is uncommon. Peculiar clinical presentations include the so-called “facies leonina” and the onset of specific skin lesions at sites of previous herpes simplex or herpes zoster eruptions (Figs 19.1 and 19.2) [4]. These latter were often classified in the past as pseudolymphoma, but in most cases represent in fact specific cutaneous manifestations of the disease triggered by the immune response to the viruses [4].

In patients with B-CLL, cutaneous tumors arising at typical sites of Borrelia burgdorferi-associated lymphocytoma cutis (nipple, scrotum, earlobe) represent specific manifestations of the disease caused by infection with B. burgdorferi (Fig. 19.3) [5]. Lesions arising on the nipple were well known in the past and were termed “leukemia lymphatica mammillae” in old textbooks. Besides specific manifestations at sites typical of Borrelia-induced lymphocytoma, in one case neoplastic infiltrates of B-CLL have also been observed at the site of Borrelia-associated erythema migrans [6].

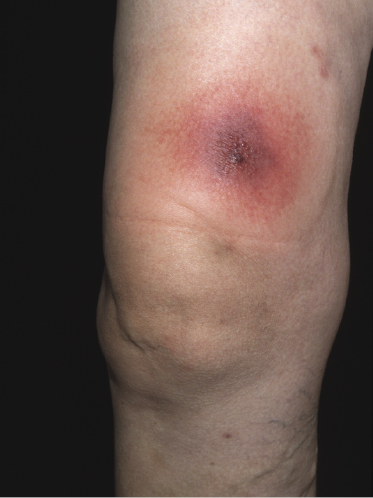

Exaggerated arthropod bite-like reactions are characterized by solitary, localized or generalized erythematous or hemorrhagic areas of skin infiltration, sometimes showing tense bullae (Fig. 19.4).

Histopathology, Immunophenotype, and Molecular Genetics

Histopathology

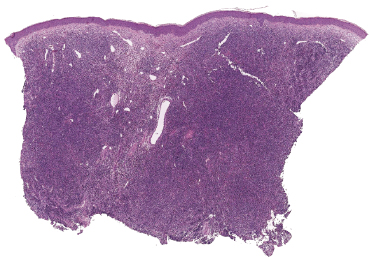

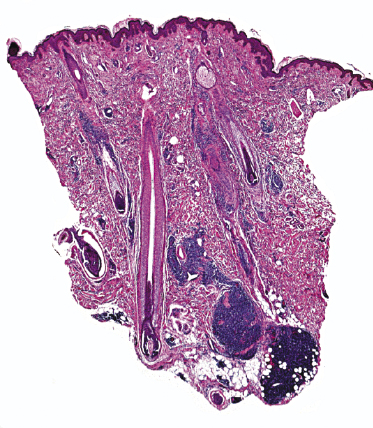

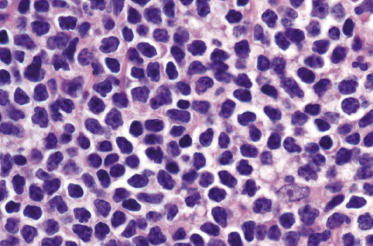

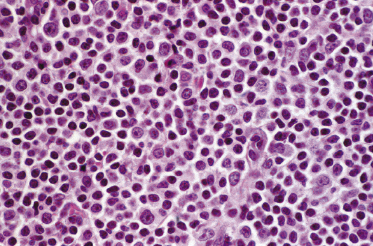

Histology of specific manifestations of B-CLL may show either patchy, perivascular, and periadnexal lymphoid clusters or the presence of dense, monomorphous, nodular, or diffuse infiltrates of lymphocytes (Fig. 19.5) [4]. The subcutaneous fat is almost invariably involved (Fig. 19.6). The infiltrate is composed predominantly of small hyperchromatic lymphocytes without prominent atypical features (Fig. 19.7). Small nodular areas with larger cells showing features of prolymphocytes or paraimmunoblasts (so-called “proliferation centers”) can be observed occasionally (Fig. 19.8) [4]. In some cases other cells such as eosinophils and epithelioid histiocytes can be found.

In patients with B-CLL, neoplastic B-lymphocytes may be observed in biopsy specimens of different cutaneous conditions, representing specific manifestations of the disease at sites of skin inflammation [4–7]. In these cases, the neoplastic lymphocytes of the B-CLL are admixed with variable numbers of reactive cells (T lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes – sometimes with the formation of small granulomas, eosinophils, neutrophils). As already mentioned, some cases of exaggerated arthropod bite-like reactions in B-CLL patients are characterized by the presence of neoplastic cells besides T-lymphocytes, histiocytes, and large numbers of eosinophils (Fig. 19.9).

A case of cutaneous “composite” lymphoma with features of both mycosis fungoides and B-CLL has been observed [12], possibly representing a further example of migration of neoplastic B-lymphocytes at sites of various skin disorders (see also Teaching case 19.1). I have also observed a case of cutaneous intravascular large T-cell lymphoma arising in a patient with B-CLL, characterized by dermal vessels filled with cells of the intravascular lymphoma and surrounded by perivascular infiltrates of CD20+/CD5+ small lymphocytes of the B-CLL. In the lymph nodes, composite lymphomas can be due to the association of two non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) types or of a Hodgkin lymphoma with an NHL. In the skin, composite lymphomas are very rare and involve only NHLs.

Immunophenotype and Molecular Genetics

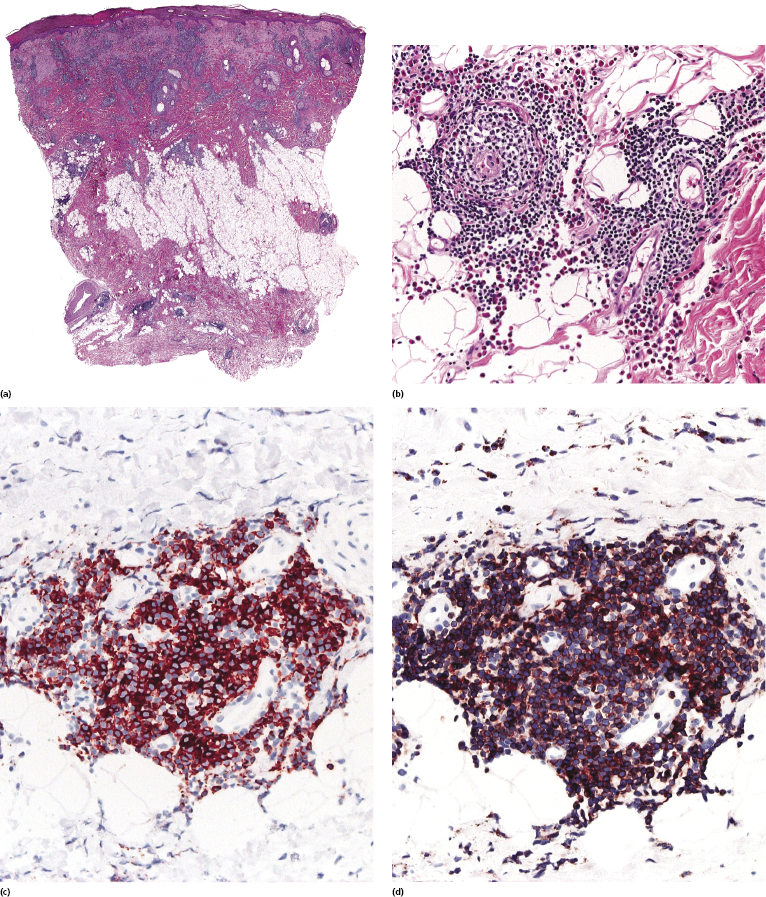

Immunohistology reveals the presence of B lymphocytes characterized by an aberrant immunophenotype (CD20+, CD5+, CD43+) and by a monoclonal expression of immunoglobulin light chains (Fig. 19.10) [2]. CD23 is usually positive and CD5 may be negative in some cases. A variable population of reactive T lymphocytes may be present.

The zeta-chain-associated protein kinase 70 (ZAP-70), a protein that is part of the T-cell receptor, correlates with the mutation status of B-CLL and is expressed in a subset of cases with a worse prognosis [13, 14].

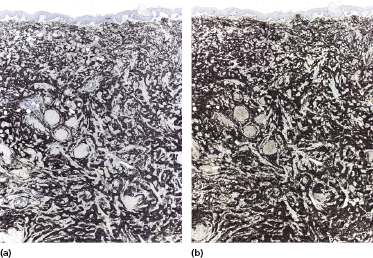

Molecular genetics shows in most cases a monoclonal rearrangement of the immunoglobulin (Ig) genes. There is evidence that two relevant prognostic subgroups of B-CLL can be defined according to the presence or absence of somatic hypermutations in the neoplastic cells [1, 14]. Reports of cutaneous involvement in patients with B-CLL did not mention the mutation status of the original leukemia, so data on the frequency of specific skin manifestations in the two subtypes are lacking.

Treatment and Prognosis

Prognosis seems not to be affected by skin involvement [2]. The treatment must be planned according to the hematologic findings and the mutation status.

Small solitary or clustered skin lesions may be removed surgically or by CO2 laser vaporization. Larger lesions may be treated by radiotherapy. Positive responses to UV-B therapy, cladribine, and alemtuzumab have been reported [15, 16]. Chemotherapy should be used only if the hematological background requires it. For patients who are in good general condition, therapy with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and anti-CD20 antibody represents the current standard treatment. For patients in bad general condition, treatment with anti-CD20 antibody in association with chlorambucil is considered currently as an appropriate treatment. Rarely skin manifestations may regress slowly without any specific treatment [17].

Patients with somatic hypermutations (mutated B-CLL) have a better prognosis than those without mutations (unmutated B-CLL), especially in earlier stages of the disease.

Progression to Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (Richter Syndrome)

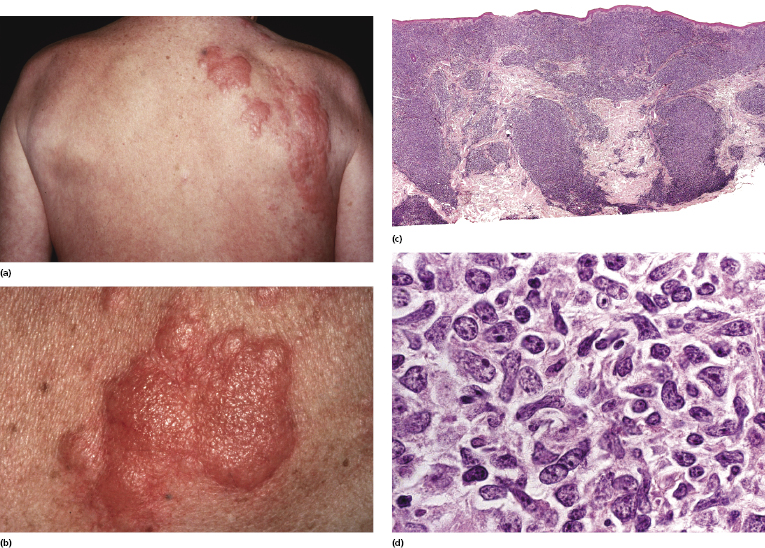

Large cell transformation of B-CLL (Richter syndrome) has been reported occasionally in the skin [2, 18–23]. A role for Epstein–Barr virus has been postulated in transformation of B-CLL, but the exact etiology remains unclear. Patients present clinically with solitary or multiple, large cutaneous/subcutaneous tumors (Fig. 19.11a). Skin lesions may be localized at the site of previous herpes zoster eruption (Fig. 19.12a and b). Histology reveals features of a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with many centroblasts and immunoblasts (Fig. 19.12c and d). Immunohistology shows positivity for B-cell markers, often with an aberrant profile similar to that described above (CD20+, CD5+, CD43+) and with monoclonal expression of immunoglobulin light chains.

Molecular genetics reveals the presence of a monoclonal rearrangement of the Ig genes. The clone may or may not be the same as that observed in the lymphocytes of the preceding B-CLL, meaning that in some cases Richter syndrome represents the occurrence of a high-grade lymphoma unrelated to the previous B-CLL (so-called “second lymphoma”) [18]. It seems that Richter syndrome in unmutated B-CLL is usually clonally related to the original neoplasm, whereas in mutated B-CLL it represents more often a second lymphoma. The prognosis of patients with cutaneous Richter syndrome (and with Richter syndrome in general) is usually poor and treatment is ineffective [2, 21]. Rare cases with exclusive cutaneous involvement and prolonged survival have been reported [22, 23].

True skin lesions of Richter syndrome should be distinguished from the rare onset of a primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma in patients with B-CLL, as the prognosis and management are different [20].

Full access? Get Clinical Tree