Other Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphomas

Besides the lymphoma entities discussed in previous chapters, there are a few reports on other types of B-cell lymphoma arising primary in the skin. In addition, most malignant B-cell lymphomas observed at extracutaneous sites may secondarily involve the skin, especially in the later stages. The clinicopathologic features of skin manifestations of the most important of these cases are summarized in the following sections.

Cutaneous EBV+ Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma of the Elderly

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly has been included as a distinct entity in the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues [1]. This type of lymphoma is defined as an EBV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma occurring in patients older than 50 years without any known immunodeficiency and without prior lymphoma [1–3]. The disease seems to be more common in Asian countries and in Mexico, and is relatively rare in Western populations [4–8]. The number of neoplastic cells positive for EBV necessary to make a diagnosis of EBV+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly varied from ≥20% to nearly all cells in different publications, thus representing a factor of uncertainty in the definition of the disease.

In the context of the discussion concerning EBV+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly it should be remembered that several lymphoproliferative disorders are associated with EBV infection, including benign and malignant proliferations with natural killer (NK)-, T-, or B-cell phenotypes such as classical Hodgkin lymphoma, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, primary effusion lymphoma, plasmablastic lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, some types of NK/T-cell lymphoma, and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders, among others (see also Table 1.5 in Chapter 1). Distinction among these groups may be very difficult, and some of the EBV+ entities may represent a spectrum from reactive hyperplasia to lymphoma. These cases can be classified properly only when the presence of EBV is considered within the general context. For example, hydroa vacciniforme-like lymphoma may show overlapping histopathologic and phenotypic features with other cytotoxic NK/T-cell lymphomas, but the constellation of clinical findings, the racial background, and the peculiar clinical aspects allow a precise categorization. In the same way, cutaneous B-cell infiltrates associated with EBV may be classified precisely only upon correlation with the clinical features and with data concerning the presence or absence of immune suppression.

EBV+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly is probably linked to aging and decreased competence of the immune system (“immunosenescence”). It represents a post-germinal center B-cell neoplasm characterized by prominent nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation [9].

Clinical Features

EBV+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly arises mostly in the lymph nodes but the skin may be affected, usually showing localized or generalized infiltrated plaques and tumors. Lesions are usually not ulcerated. Cutaneous involvement is observed more commonly in Asiatic than in Western patients [6, 10]. Some patients may present with a solitary tumor on the leg, prompting the differential diagnosis with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type [11, 12].

Histopathology, Immunophenotype, and Molecular Genetics

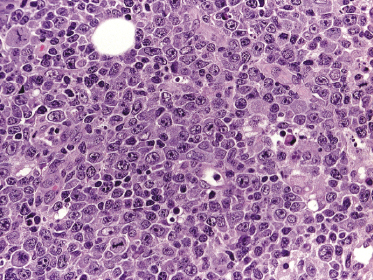

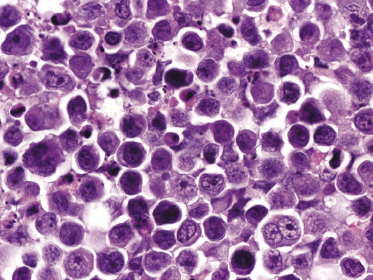

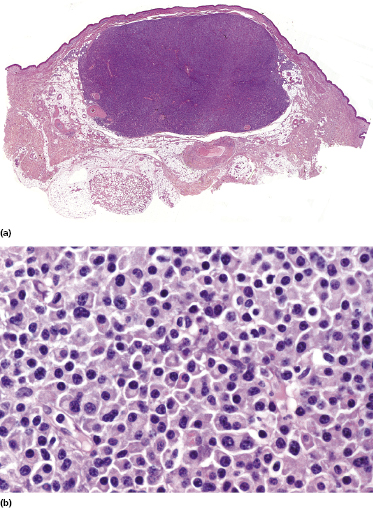

The histopathologic pattern may be polymorphous or monomorphic. Polymorphic cases show a mixed infiltrate with the presence of large cells resembling Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells as well as centroblasts, immunoblasts, and plasmablasts, admixed with a variable component of reactive cells including small lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes. Monomorphic cases are characterized by predominance of large rounded B-cells (immunoblasts), sometimes showing features of plasmablasts (Fig. 15.1). Both variants are strongly positive for EBV. Necrosis is common in affected lymph nodes, but less so in skin lesions. Monomorphic cases reveal the picture of a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [12, 13].

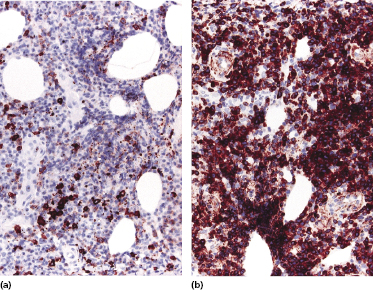

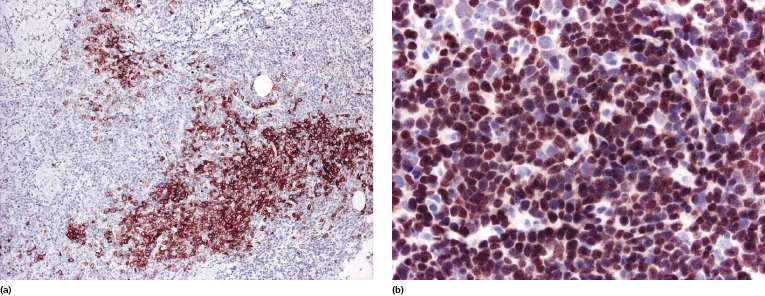

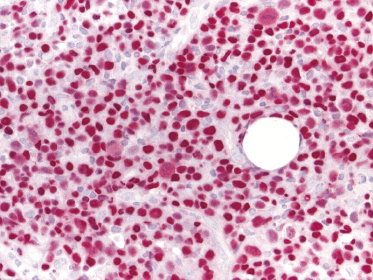

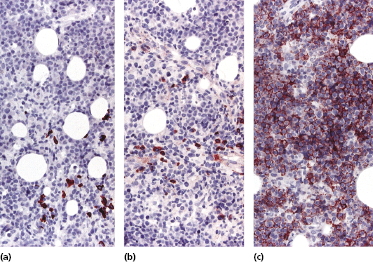

In contrast to conventional diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, cases of EBV+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly may show loss of CD20 expression, but retain CD79a and PAX-5 positivity (Fig. 15.2a and b). CD30 is positive on neoplastic cells in the majority of cases, as well as multiple myeloma oncogene-1 (MUM-1) (Fig. 15.3a and b). Detection of EBV by in situ hybridization is a prerequisite for the diagnosis (Fig. 15.4).

EBV+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly is characterized by prominent NF-κB activation [9]. Immunoglobulin (Ig) genes are usually monoclonally rearranged. Cytogenetic complexity is low and it has been suggested that for lymphomagenesis the EBV oncogenic properties are sufficient in the context of immunosenescence [9]. Although both entities have the signature of activated B lymphocytes, some genes are differentially expressed in EBV+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly as compared to EBV− diffuse large B-cell lymphomas [8].

Treatment and Prognosis

EBV+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly is a very aggressive lymphoma with a median survival of about 2 years. The treatment is often complicated by the advanced age of patients. The histopathologic pattern (polymorphic or monomorphic) does not have any prognostic meaning.

Different therapeutic approaches based on tumor biology and association with EBV infection have been suggested. Systemic chemotherapy as well as anti-CD20 antibody (rituximab) and anti-CD30 antibody (brentuximab) may be used to target tumor cells. EBV-specific adoptive immunotherapy, miRNA-targeted therapy, and EBV lytic phase induction followed by anti-herpes virus drugs have been proposed as possible treatment strategies [8], but at present there is a lack of comprehensive studies. The use of bortezomib or other inhibitors of the NF-κB pathway may be another alternative approach, based on the prominent NF-κB activation in tumor cells [8].

Specific Cutaneous Manifestations in Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Mantle cell lymphoma is a rare B-cell lymphoma deriving from the inner mantle zone of lymphoid follicles [14]. Cutaneous involvement is uncommon, but in rare cases specific skin lesions may be the first manifestation of the disease [15–18]. A few examples of mantle cell lymphoma arising primary in the skin have been reported, but the uniform good prognosis observed in these patients casts doubt on the classification of these cases [19]. Personally, I have never come across cases of primary cutaneous mantle cell lymphoma.

Clinical Features

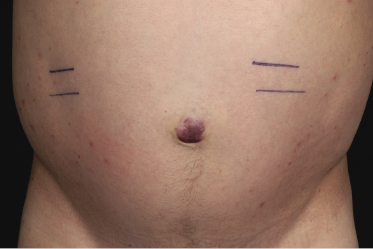

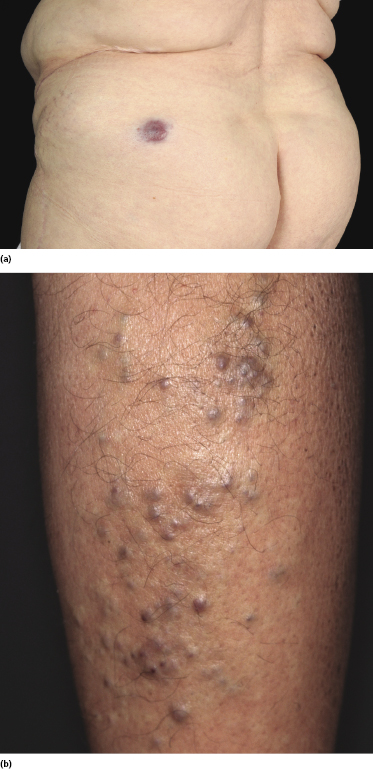

Patients are middle-aged or older individuals, with a predominance of males. Clinically, the lesions are characterized by solitary or, more commonly, multiple reddish tumors. I have observed one patient with a solitary tumor on the navel, presenting clinically with the picture of so-called Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule as a recurrence of mantle cell lymphoma with diffuse peritoneal involvement and ascites (Fig. 15.5).

Histopathology, Immunophenotype, and Molecular Genetics

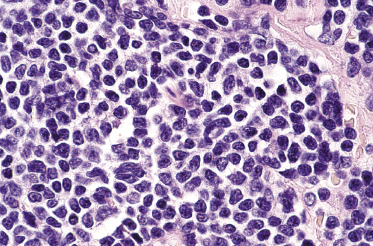

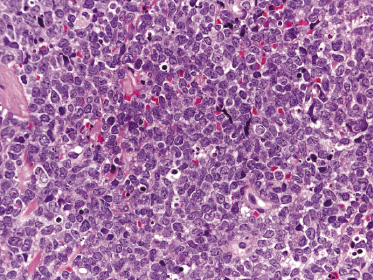

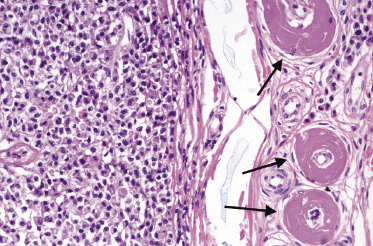

Histology shows diffuse monomorphous infiltrates throughout the entire dermis and subcutis, composed of small- to medium-sized lymphocytes with irregular nuclei (Fig. 15.6). The blastoid variant, with either lymphoblast-like or large cleaved cells, is frequently observed in cutaneous infiltrates, probably reflecting an increased propensity to skin involvement by tumors that undergo progression (Fig. 15.7).

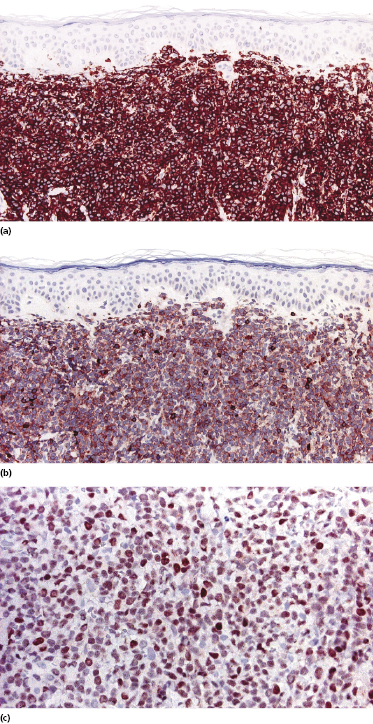

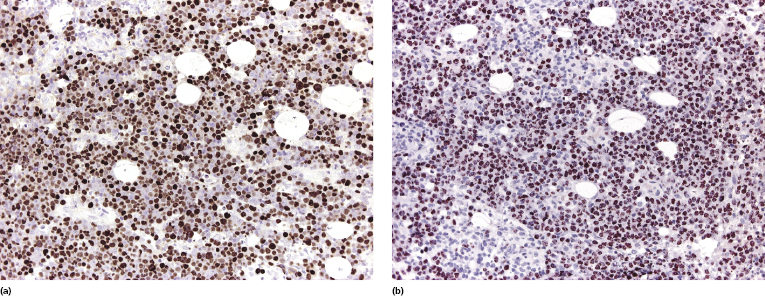

Immunohistology is characterized by positivity for CD20 and CD5 (Fig. 15.8a and b) and negativity for other T-cell markers. In contrast to cases of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL), CD23 is negative or only weakly expressed in neoplastic cells of mantle cell lymphoma. Nuclear staining for cyclin-D1 is a helpful tool for the differentiation of cutaneous mantle cell lymphoma from other malignant B-cell lymphomas, especially B-CLL and B-lymphoblastic lymphoma (Fig. 15.8c) [20].

Molecular analyses reveal a monoclonal rearrangement of the Ig genes in the majority of cases. The typical t(11;14)(q13;q32) can be demonstrated by conventional cytogenetics, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), or polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Treatment and Prognosis

The treatment of choice is systemic chemotherapy, often followed by stem cell transplantation. The prognosis is poor and the median survival is less than 5 years.

Specific Cutaneous Manifestations in Extracavitary Primary Effusion Lymphoma

Primary effusion lymphoma is a large B-cell lymphoma presenting in serous effusions and associated with herpes virus-8 (HHV-8) [21], usually arising in individuals infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Tumors presenting as solid masses rather than serous effusions are classified as extracavitary primary effusion lymphoma [21, 22]. Cutaneous involvement may be seen in these cases as a secondary lymphoma manifestation, but primary cutaneous involvement has not been observed.

Clinical Features

Extracavitary primary effusion lymphoma arises usually in HIV+ young or middle-aged adults. Cutaneous involvement presents with nondescript, localized, or generalized cutaneous or subcutaneous nodules (Fig. 15.9).

It should be underlined that a diagnosis of cutaneous involvement by extracavitary primary effusion lymphoma should be confirmed by the presence of a primary tumor at extracutaneous sites.

Histopathology, Immunophenotype, and Molecular Genetics

Histology shows cutaneous or subcutaneous infiltrates comprised of sheets of large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and with anaplastic or plasmablastic appearance (Fig. 15.10). CD20 and CD79a are usually negative, but markers of plasma cell differentiation (CD38, CD138) are positive (Fig. 15.11). Aberrant expression of T-cell markers may be observed, representing a pitfall in the diagnosis. HHV-8 and EBV are expressed in virtually all neoplastic cells (Fig. 15.12). In some cases, cutaneous extracavitary primary effusion lymphoma may mimic histopathologically anaplastic large cell lymphoma and show expression of CD30, thus representing a diagnostic pitfall [23].

The Ig genes are clonally rearranged. Gains in chromosomes 12 and X have been reported. The gene expression profile shows plasma cell and EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell features.

Treatment and Prognosis

Patients are treated with systemic chemotherapy, but the prognosis is very poor with a median survival of <6 months.

Specific Cutaneous Manifestations in Multiple Myeloma

Several cases of primary cutaneous plasmacytoma have been reported in the past, but in the WHO–European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) classification of cutaneous lymphomas most of these cases were reclassified as variants of marginal zone lymphoma with predominant plasmacytic differentiation (see Chapter 12) [24]. In this context, the existence of genuine primary cutaneous plasmacytoma seems unlikely and cases of true plasmacytoma arising in the skin represent almost invariably secondary manifestations of multiple myeloma [25].

Clinical Features

Patients present clinically with solitary, clustered, or generalized cutaneous or subcutaneous plaques or tumors. The lesions often have a characteristic brown or purpuric color (Fig. 15.13).

Histopathology, Immunophenotype, and Molecular Genetics

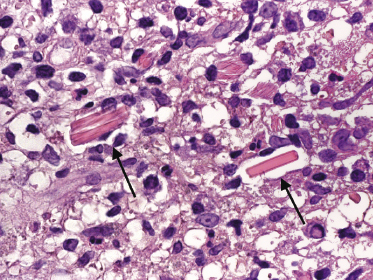

Cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma consist of dense nodules and/or sheets of cells within the entire dermis and subcutis. Mature and immature plasma cells with varying degrees of atypia predominate (Fig. 15.14). Dutcher bodies and Russell bodies are found occasionally. Small reactive lymphocytes are few or absent. Amyloid deposits may be observed within and/or surrounding the neoplastic infiltrates, particularly around blood vessels (Fig. 15.15). Crystalloid intracytoplasmic inclusions within histiocytes and macrophages may also occur (“crystal storing histiocytosis”), representing intracellular deposits of immunoglobulins with peculiar geometric shapes (Fig. 15.16) [26, 27]. Crystal storing histiocytosis is mostly related to multiple myeloma, but cases have been observed also in association with other conditions such as lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, MALT lymphoma, and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, and rarely without association with an underlying lymphoproliferative disorder.

Neoplastic plasma cells contain cytoplasmic immunoglobulins (usually IgA) and show monoclonal expression of one immunoglobulin light chain. Leukocyte common antigen (CD45) and most B-cell-associated markers are negative, but cells can be stained by CD38 or CD138 in most cases and by CD79a in some cases. Immunohistochemical expression of cytokeratins, HMB45 and CD30, can be observed within neoplastic plasma cells, representing a potential source of diagnostic error.

Molecular analysis usually reveals a monoclonal rearrangement of the Ig genes.

Treatment and Prognosis

The treatment is tailored on the systemic manifestations. Radiotherapy may be administered for solitary cutaneous tumors.

The prognosis of cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma is poor. Analysis of data concerning cases of cutaneous plasmacytoma published in the literature, however, is hindered by the inclusion of cases that today would be classified as cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma, plasmacytic variant.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree