Fig. 1

Initial injury X-rays demonstrating significant bone injury

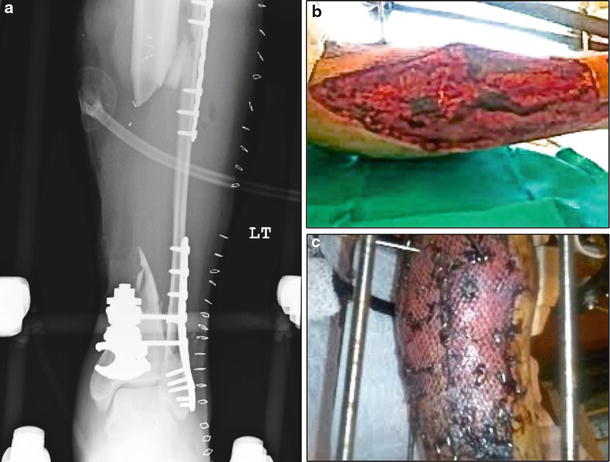

Fig. 2

Post-operative X-rays following initial irrigation and debridement, excision of the bone, and placement of spanning external fixator

Fig. 3

Post-operative X-rays following repeat irrigation, debridement, revision of the external fixator, and open reduction and internal fixation of the left complex fibula fracture. Clinical photographs demonstrate the soft tissue reconstruction

3 Preoperative Problem List

1.

18 cm tibial bone defect

2.

Extensive soft tissue reconstruction

3.

Segmental fibula fracture with previous open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF)

4.

Syndesmosis injury with previous ORIF

5.

Prior grossly contaminated open wound

4 Treatment Strategy

The patient underwent initial serial irrigations, debridements, and antibiotic bead exchanges. There was radical bone resection completed, in order to minimize the long-term risk for infection, resulting in a final tibial bone defect of 18 cm. The segmental fibula and syndesmosis injuries had been initially treated with ORIF; therefore, whenever possible, the previous fixation was left intact in order to provide additional stability and to assist with judging the length, alignment, and rotation of the tibia. Following soft tissue reconstruction, the temporary spanning external fixator was removed, a double-level tibial corticotomy was completed, and an Ilizarov external fixator was placed to allow for double-level bone transport from proximal to distal. Collaboration with a plastic surgeon was important for soft tissue coverage and for close follow-up during the bone transport treatment. Following a 7-day latency period, distraction was initiated with follow-up every 2 weeks, with precise measurements between all rings, in order to ensure symmetric distraction, and patient compliance was occurring. Each of the corticotomy sites had different distraction rates throughout treatment, which was based on the radiographic appearance of the regenerate formation. The patient underwent frame revisions to allow deformity correction with Taylor spatial struts and later compression at the docking sites, with threaded rods, at different time periods during treatment.

5 Basic Principles

In complex open tibia fractures, initial stabilization of the tibia fracture with external fixation can provide stability for repeat irrigations and debridements and for soft tissue reconstruction. The decision for limb salvage must be based on predicting a good functional recovery with a limb that is well aligned with the patient’s functional and cosmetic expectations. Once limb salvage is deemed feasible and desirable, appropriate bone and soft tissue resection is important for adequate debridement, which can result in significant bone defects. Keating et al. (2005) summarized a treatment algorithm based on the extent of bone loss and suggested that greater than 6 cm bone loss may benefit from treatment with bone transport. At the time of definitive bone resection, perfectly flat tibial cuts that are perpendicular to the long axis of the tibial shaft are important for later docking site contact (Fig. 4). Bone transport, or distraction osteogenesis, relies on the law of tension-stress, where gradual and constant traction stress causes increased metabolic activity, which allows for osteogenesis (Ilizarov 1989a, b

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree