Chapter 13 The Periareolar Approach for Augmentation

The periareolar incision approach to breast augmentation is a realistic option for patients who request the incision approach and for surgeons who prefer it.Chapter 9 details the relative advantages and tradeoffs of the periareolar approach compared to other incision approaches. Proponents of the periareolar approach emphasize the superior scar qualities of periareolar scars compared to inframammary scars, and although there is no valid scientific evidence in comparative cohorts to validate the claim, this approach is very popular in some areas of Europe and South America. Surgeons can place implants in all pocket locations via the periareolar approach. However, accuracy and control of dual plane techniques is limited because precise control of the degree of detachment at the parenchyma-pectoralis interface is not as accurate compared to the inframammary approach. Dual plane 1 procedures via the periareolar approach are often inadvertently dual plane 2 or 3 procedures and risks of pectoralis banding, windowshading, or animation deformities are greater when surgeons develop a dual plane pocket via a periareolar approach.

Instrumentation

Surgeons can perform periareolar augmentation with a wide variety of instruments. Specific instruments increase control and accuracy in the operation, and facilitate implant insertion and positioning. Rake retractors (Figure 13-1) lift and stabilize the skin edges after the initial incision and enable the surgeon to accurately tunnel through or around breast parenchyma to the level of the desired pocket. A pair of double ended retractors, each with a shorter and a longer blade, is indispensable for opposing retraction during mid depth dissection, initial dissection of the pocket plane, and to provide optimal access for implant insertion (Figure 13-2). The most effective dissecting instrument for initial dissection through dermis, subcutaneous tissue, and breast parenchyma is a handswitching, needlepoint, electrocautery pencil (Figure 13-3, upper). For dissection of a submammary, partial retropectoral or dual plane pocket and for hemostatic control in all areas, a handswitching, monopolar, needlepoint electrocautery forceps is the most effective instrument, enabling surgeons to dissect and control bleeders with a single instrument (Figure 13-3, lower).

insertion and positioning. Rake retractors (Figure 13-1) lift and stabilize the skin edges after the initial incision and enable the surgeon to accurately tunnel through or around breast parenchyma to the level of the desired pocket. A pair of double ended retractors, each with a shorter and a longer blade, is indispensable for opposing retraction during mid depth dissection, initial dissection of the pocket plane, and to provide optimal access for implant insertion (Figure 13-2). The most effective dissecting instrument for initial dissection through dermis, subcutaneous tissue, and breast parenchyma is a handswitching, needlepoint, electrocautery pencil (Figure 13-3, upper). For dissection of a submammary, partial retropectoral or dual plane pocket and for hemostatic control in all areas, a handswitching, monopolar, needlepoint electrocautery forceps is the most effective instrument, enabling surgeons to dissect and control bleeders with a single instrument (Figure 13-3, lower).

A fiberoptic retractor with a blade length of 10–15 cm and a blade width of 2.5–3 cm provides optimal exposure in more distal areas of the pocket and facilitates dissection in breasts with considerable thickness of breast parenchyma (Figure 13-4). Long forceps with teeth and tungsten carbide inserts and a pair of Lahey clamps (Figure 13-5) enable the surgeon to grasp the pectoralis for initial incision access to the subpectoral plane and for subsequent initial pocket dissection.

Figure 13-4 Fiberoptic retractor with smoke evacuation capability for dissection in distal areas of the pocket.

Incision Location and Length

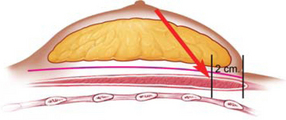

Incision length is largely determined by the diameter of the areola, and surgeons should consider alternative incision locations when areola diameter is less than 3 cm. Although surgeons have reported various extensions of a periareolar incision onto the skin in patients with small areolas, the potential compromise in the resulting scar on the most prominent portion of the breast is illogical compared to choosing an alternative incision location. With full height, anatomic, form stable silicone gel implants, surgeons should carefully consider alternative incision approaches when planning to use implants with greater than a 12 cm base width or in patients with an areolar diameter of 4 cm or less. Placing this type of implant with these dimensions through a smaller periareolar incision poses illogical risks of damage to the implant and excessive trauma to the skin edges.

Preoperative Markings

To define the level of the desired, postoperative inframammary fold, the surgeon places the tip of a flexible tape measure at the level of the nipple, maximally lifts the nipple upward to stretch the lower pole skin of the breast, and places a dot at or beneath the existing inframammary fold to define the desired, new nipple-to-inframammary fold distance (Figure 13-6)

Preoperative markings begin by placing a dot at the sternal notch and xiphoid and aligning a row of dots between these two points to define a visual midline. Placing a row of dots 1.5 cm lateral to the midline row defines a 3 cm intermammary distance and defines the maximal extent of safe medial pocket dissection to avoid medial perforating vessels and risking optimal soft tissue coverage in this critical area. The surgeon then outlines the existing inframammary fold, and depending on the base width of the proposed implant, defines the level of the new, desired inframammary fold using the High Five™ process and measurements detailed inChapter 7. To define the level of the desired, postoperative inframammary fold, the surgeon places the tip of a flexible tape measure at the level of the nipple, maximally lifts the nipple upward to stretch the lower pole skin of the breast, and places a dot at or beneath the existing inframammary fold to define the desired, new nipple-to-inframammary fold distance (Figure 13-6). As a final step, the surgeon marks the periareolar incision line.

Although it is possible for surgeons to adjust the level of the inframammary fold intraoperatively via the periareolar approach, visual intraoperative judgments of optimal fold level are subject to many variables of patient positioning that make visual judgments less accurate compared to objective, quantitative, planned measurements. Surgeons can always check fold levels visually, but absent quantitative tissue measurements and planning preoperatively, the check is always a subjective opinion compared to an objective, planned measurement.

Anesthesia and Local Anesthetic Instillation

Chapter 15 is devoted to preoperative care, anesthesia, and postoperative care. Optimal, state-of-the-art breast augmentation and optimal recovery require general anesthesia and muscle relaxants. General anesthesia can reduce the amount of intraoperative sedative and narcotic drugs a patient requires while enabling surgeons to perform a more accurate, controlled operation and dramatically reducing patient recovery times.1 Instillation of a vasoconstrictive agent along the incision line may reduce dermal bleeding, but instillation of local anesthetic into any other area of the breast or pocket is unnecessary and has the following potential risks: (1) multiple small hematomas within the breast parenchyma, (2) increased electrical resistance in all infiltrated tissues that decrease the efficacy of electrocautery dissection, (3) increased risks of pneumothorax with deeper infiltration or intercostal blocks, and (4) delayed bleeding postoperatively as the effects of vasoconstrictors decrease. Intercostal blocks, instillation of local anesthetic agents into the pocket, and pain pumps are totally unnecessary for patient comfort postoperatively if surgeons apply proved processes that predictably deliver 24 hour recovery.1

Initial Incision and Tunnel Alternatives

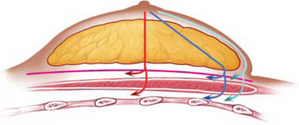

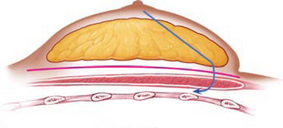

After making the initial skin incision, the surgeon places two rake retractors on the opposing skin edges and the assistant lifts and keeps the soft tissues under tension as the surgeon deepens the dissection with the needlepoint electrocautery pencil (Figure 13-7). The surgeon has three basic alternatives for access to the submammary, subfascial, or subpectoral spaces: (1) dissect superficially in a deep subcutaneous plane inferiorly and around the breast parenchyma inferiorly, (2) dissect directly posteriorly through breast parenchyma to the surface of the pectoralis major muscle, or (3) dissect obliquely from the incision to a level inferiorly that is approximately 2 cm above or superior to the desired, postoperative inframammary fold (Figure 13-8). While dissection superficially in a deep subcutaneous plane inferiorly and around the breast parenchyma inferiorly may seem logical to avoid dissection through breast parenchyma, this approach has several distinct tradeoffs that include increased postoperative ecchymosis or fluid accumulations in the subcutaneous tunnel, possible surface contour irregularities postoperatively, maldistribution of breast parenchyma over the implant, and greater technical difficulty in larger breasts.

If a surgeon plans a submammary or subfascial pocket location, the surgeon should select either a straight posterior or oblique approach through the parenchyma (Figure 13-9). For a partial retropectoral pocket, if the surgeon plans a muscle splitting or lateral approach to the subpectoral space, a directly posterior dissection is most logical (Figure 13-10). If, however, the surgeon plans a dual plane pocket, the most logical approach is obliquely through the parenchyma on a line from the incision to a level inferiorly that is approximately 2 cm above or superior to the desired, postoperative inframammary fold (Figure 13-11). For a dual plane pocket, this is the level at which the surgeon should divide inferior origins of the pectoralis across the inframammary fold for access to the subpectoral space.

Entering the Submammary or Subfascial Spaces

As the dissection deepens to 3–4 cm, the surgeon places opposing double ended retractors for deeper exposure, and then removes the rake retractors (Figure 13-12)

The surgeon can dissect either directly posteriorly or obliquely through breast parenchyma to access the submammary or subfascial spaces, using the handswitching, needlepoint electrocautery pencil with a blended cut and coagulation current that optimizes hemostasis. To minimize postoperative morbidity, surgeons should control bleeding very meticulously during tunnel creation through parenchyma. As the dissection deepens to 3–4 cm, the surgeon places opposing double ended retractors for deeper exposure, and then removes the rake retractors (Figure 13-12). As discussed inChapter 8, the pectoralis fascia is less than 0.2 mm thick in most patients, so a subfascial pocket does not add any meaningful coverage over any type of breast implant, and has not been shown in scientifically valid, comparative cohorts to have any proved advantage over a submammary pocket. Nevertheless, surgeons can elect to dissect superficial or deep to the pectoralis fascia for access to submammary or subfascial pocket locations. At the level of the pectoralis fascia or to increase exposure at any time, the surgeon switches from the shorter blade to the longer blade of the opposing double ended retractors.

The surgeon can dissect either directly posteriorly or obliquely through breast parenchyma to access the submammary or subfascial spaces, using the handswitching, needlepoint electrocautery pencil with a blended cut and coagulation current that optimizes hemostasis. To minimize postoperative morbidity, surgeons should control bleeding very meticulously during tunnel creation through parenchyma. As the dissection deepens to 3–4 cm, the surgeon places opposing double ended retractors for deeper exposure, and then removes the rake retractors (Figure 13-12). As discussed inChapter 8, the pectoralis fascia is less than 0.2 mm thick in most patients, so a subfascial pocket does not add any meaningful coverage over any type of breast implant, and has not been shown in scientifically valid, comparative cohorts to have any proved advantage over a submammary pocket. Nevertheless, surgeons can elect to dissect superficial or deep to the pectoralis fascia for access to submammary or subfascial pocket locations. At the level of the pectoralis fascia or to increase exposure at any time, the surgeon switches from the shorter blade to the longer blade of the opposing double ended retractors.

Entering the Retropectoral Space and Dual Plane Alternatives

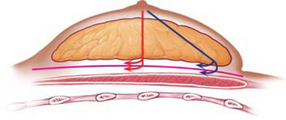

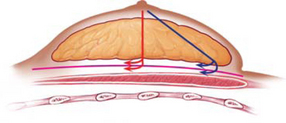

When a surgeon plans a dual plane pocket location via the periareolar approach, the parenchymal tunnel should angle obliquely inferior from the incision to a level 2 cm above the desired, new inframammary fold level defined by the High Five™ System (Figure 13-13)

When a surgeon plans a dual plane pocket location via the periareolar approach, the parenchymal tunnel should angle obliquely inferior from the incision to a level 2 cm above the desired, new inframammary fold level defined by the High Five™ System (Figure 13-13). At this level, the surgeon next dissects medially and laterally to expose a band of lower pectoralis major muscle 2–3 cm wide transversely, carefully avoiding any dissection inferiorly past a level at least 2–3 cm above the desired, new inframammary fold. By aiming above the desired, new fold level, the surgeon avoids the retractor tip inadvertently lifting the inferior tissues and dissecting the pocket border excessively inferiorly. After dividing pectoralis major muscle origins across the inframammary fold, the surgeon can incrementally lower the pocket border and fold to the precise, desired level.

When a surgeon plans a dual plane pocket location via the periareolar approach, the parenchymal tunnel should angle obliquely inferior from the incision to a level 2 cm above the desired, new inframammary fold level defined by the High Five™ System (Figure 13-13). At this level, the surgeon next dissects medially and laterally to expose a band of lower pectoralis major muscle 2–3 cm wide transversely, carefully avoiding any dissection inferiorly past a level at least 2–3 cm above the desired, new inframammary fold. By aiming above the desired, new fold level, the surgeon avoids the retractor tip inadvertently lifting the inferior tissues and dissecting the pocket border excessively inferiorly. After dividing pectoralis major muscle origins across the inframammary fold, the surgeon can incrementally lower the pocket border and fold to the precise, desired level.

To facilitate retraction of the pectoralis for dissection of the subpectoral pocket, surgeons should avoid excessive initial separation of breast parenchyma from the anterior surface of the pectoralis major superior to the desired level of division of pectoralis origins, even if the surgeon is planning a dual plane 2 or 3 pocket. Surgeons should always develop the subpectoral portion of the pocket superiorly first, before performing any separation of parenchyma off the pectoralis, to leave parenchyma–muscle attachments intact and prevent excessive upward movement and banding of the inferior cut border of the pectoralis. Surgeons should also avoid dividing inferior pectoralis origins more than 2 cm off the rib origins to avoid excessive bleeding from intramuscular vessels that increase in caliber more superiorly. The ideal level to divide pectoralis muscle origins is 1–2 cm off their rib origins to prevent retraction of cut vessels into the intercostal musculature and prolong bleeding or risk pneumothorax while trying to achieve hemostasis.

The most practical location for the periareolar incision is at the lower border of the areola from the 3 o’clock to the 9 o’clock position. Placing the incision barely inside the pigmented border of the areola prevents disrupting the natural, fading pigmentation at the areola border, but this location is most logical for patients with lighter pigmented areolas. In darker pigmented areolas, a depigmented scar in an intraareolar location is much more noticeable compared to a scar exactly at the border of the areola.

The most practical location for the periareolar incision is at the lower border of the areola from the 3 o’clock to the 9 o’clock position. Placing the incision barely inside the pigmented border of the areola prevents disrupting the natural, fading pigmentation at the areola border, but this location is most logical for patients with lighter pigmented areolas. In darker pigmented areolas, a depigmented scar in an intraareolar location is much more noticeable compared to a scar exactly at the border of the areola.

To enter the partial retropectoral pocket location (leaving origins of the pectoralis major muscle intact inferiorly across the inframammary fold), the surgeon can dissect directly posteriorly through parenchyma to the pectoralis major muscle and then split the muscle for access to the subpectoral space. Splitting the pectoralis, however, risks causing more bleeding compared to accessing the pocket laterally by lifting the lateral border of the pectoralis. If the surgeon chooses a lateral approach, the parenchymal tunnel can angle slightly laterally from the incision toward the lateral border of the pectoralis.

To enter the partial retropectoral pocket location (leaving origins of the pectoralis major muscle intact inferiorly across the inframammary fold), the surgeon can dissect directly posteriorly through parenchyma to the pectoralis major muscle and then split the muscle for access to the subpectoral space. Splitting the pectoralis, however, risks causing more bleeding compared to accessing the pocket laterally by lifting the lateral border of the pectoralis. If the surgeon chooses a lateral approach, the parenchymal tunnel can angle slightly laterally from the incision toward the lateral border of the pectoralis.