Cutaneous Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Leg Type

Cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, is a malignant lymphoma of intermediate behavior, occurring mostly on the leg(s) in elderly patients [1–2]. The nomenclature of this entity has been the source of a long controversy, but the term cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, is now established, and this lymphoma is listed as a specific entity in the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues [3]. On the other hand, it has been shown that primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, and secondary cutaneous involvement by testicular B-cell lymphoma share identical clinicopathological and immunophenotypic features [4]. It is a matter of discussion whether cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, is a specific entity per se, or does simply represent a primary cutaneous variant of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, unspecified. In fact, there are more similarities than differences between these two groups, and it has been suggested that cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, should not be considered as a separate entity, but rather classified within the group of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, unspecified [5].

Although cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, and follicle center lymphoma, diffuse type, may present morphologically with overlapping features (both are comprised of a neoplastic population of large B lymphocytes), it is crucial to distinguish them, as the latter has an indolent course with excellent prognosis. A thorough discussion of differential diagnostic features is presented in Chapter 11.

Cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, can be seen in immunocompromised patients and has been observed in association with Kaposi sarcoma, but is not specifically linked to infection by human herpesvirus (HHV)-8 [6, 7]. The presence of specific sequences of Borrelia burgdorferi DNA has been demonstrated in rare cases from countries with endemic infection [8–10].

Cases with a positive nuclear signal for Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) detected by in situ hybridization have been rarely reported in the literature [11, 12], but probably should be better classified as cutaneous EBV+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly (see Chapter 15).

It must be remembered that a diagnosis of cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, can be made only upon negative staging investigations, as any extracutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma may involve the skin secondarily. In nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, PET-CT imaging is as specific and sensitive as a biopsy in identifying bone marrow involvement, suggesting that it can replace bone marrow biopsy as the method of choice [13]. Data on cutaneous cases are not available.

Clinical Features

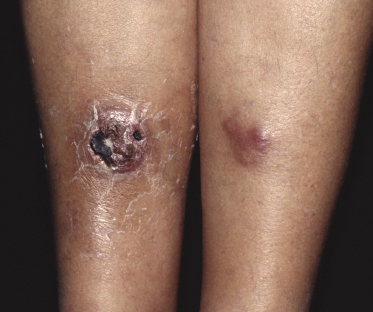

The disease predominantly affects the leg(s) of elderly patients (over 70 years of age), especially females. A wide spectrum of clinical presentations can be observed at onset: irregular, partly infiltrated patches and small, flat plaques, usually not diagnosed clinically as lymphoma (Fig. 13.1) (see Teaching case 13.1); solitary or localized, sometimes ulcerated papules or nodules (Fig. 13.2); confluent plaques and tumors covering a large part of the lower leg (Fig. 13.3); large ulcerations with infiltrated borders, which may lead to the misdiagnosis of chronic venous ulceration (“neoplastic ulcera”) (Fig. 13.4); and lesions involving both legs (Fig. 13.5). Recurrent and/or lesions in advanced stages may display features similar to the primary ones or become more widespread, usually still retaining the peculiar tropism for the legs (Fig. 13.6).

In the early phases, patients may present clinically with annular lesions that resemble erythema chronicum migrans or gyrate erythema (Fig. 13.7) [14]. In these cases, due to both the inconspicuous clinical presentation and the histopathologic features characterized by relatively sparse perivascular aggregates of cells, the correct diagnosis may be missed.

It is important to underline that lesions with similar clinical, histopathologic, and phenotypical features can arise at cutaneous sites other than the legs (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, occurs in approximately 80–85% of cases on the leg(s) only) [15]. Onset at body sites other than the legs is usually characterized by solitary or localized tumors (Fig. 13.8).

Cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, has been observed on the background of chronic lymphedema [16], but the association is most likely fortuitous.

Histopathology, Immunophenotype, and Molecular Genetics

Histopathology

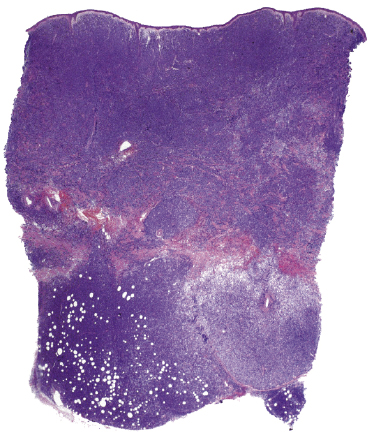

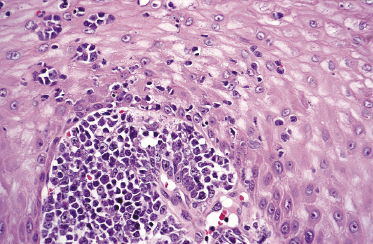

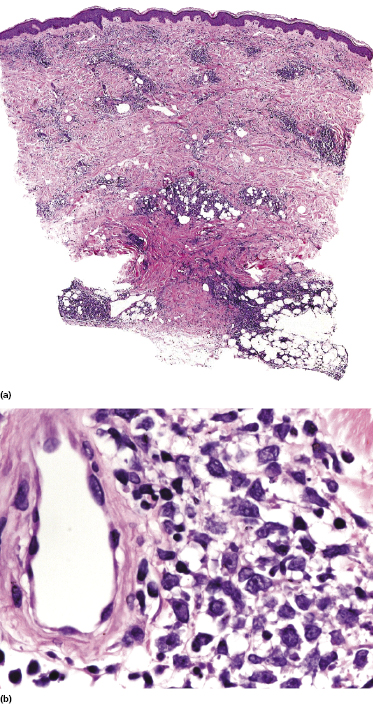

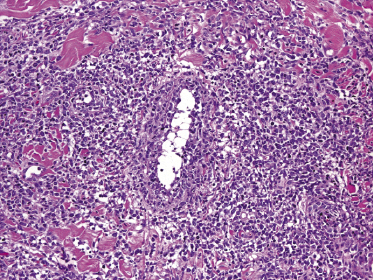

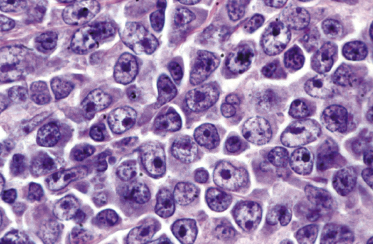

There are dense, diffuse lymphoid infiltrates within the entire dermis and subcutaneous fat (Fig. 13.9). Involvement of the epidermis by large neoplastic cells may be observed rarely, indistinguishable from Darier’s nests (Pautrier’s microabscesses) (Fig. 13.10). Rare cases may even show band-like infiltrates in the superficial and mid-dermis, simulating the histopathologic pattern of mycosis fungoides (see Teaching case 13.1). Sparse perivascular collections of large cells may be observed in early lesions and may be the source of diagnostic problems (Fig. 13.11). Angiocentricity is an uncommon finding (Fig. 13.12) [17]. The neoplastic infiltrate consists predominantly of large cells with round nuclei (immunoblasts and centroblasts) (Fig. 13.13). Reactive small lymphocytes are usually only sparse. Mitoses are frequent.

Although the predominance of spindle cells has been described in some cases [17], in my opinion most of the lesions showing this peculiar morphology represent a variant of cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, diffuse type (see Chapter 11). In rare instances, cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, may relapse with clinicopathologic features of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma [18].

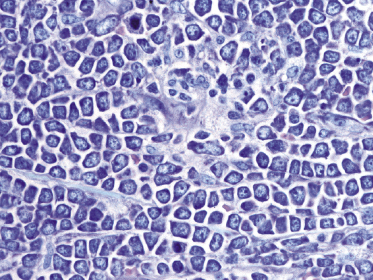

A rare histopathologic variant of cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, shows a starry sky and/or mosaic stone-like pattern with “squared” lymphocytes (Fig. 13.14). This histopathologic presentation is similar to what is observed in cutaneous Burkitt lymphoma or in cutaneous lymphoblastic lymphomas. Cases with this peculiar morphology have the same phenotype and behavior of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, and are different from so-called “Burkitt-like” lymphomas (B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma in the WHO classification).

Immunophenotype

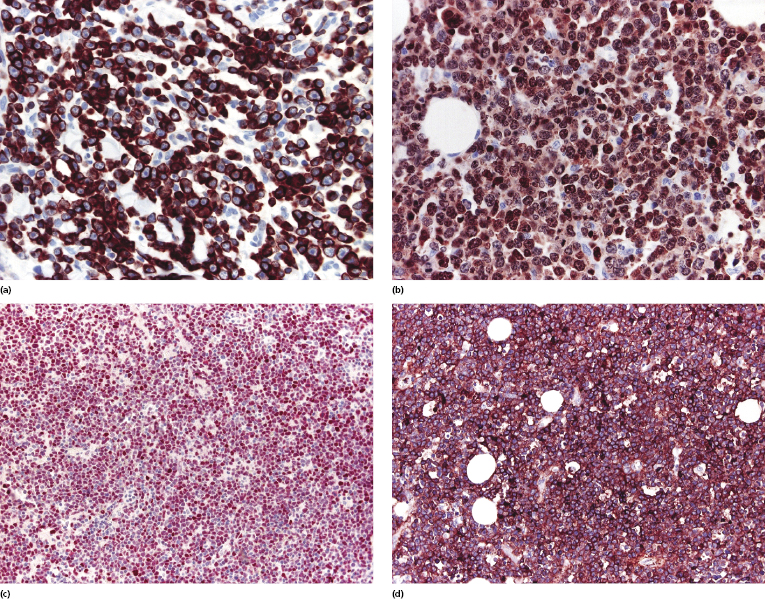

Neoplastic cells express B-cell markers (CD20, CD79a), but there can be (partial) loss of antigen expression. Bcl-2 protein, multiple myeloma oncogene-1 (MUM-1), and forkhead box protein 1 (FOX-P1) are positive in the great majority of cases (Fig. 13.15a and b) [19–21]. Rare Bcl-2− cases that otherwise fit into this group should not be classified as follicle center lymphoma. The proliferation markers usually stain a large proportion of the cells. In the majority of cases, neoplastic cells express Bcl-6 and rarely CD10, demonstrating a derivation from germinal center cells (Fig. 13.15c) [22]. IgM is strongly positive, in contrast to negativity observed in follicle center lymphoma, diffuse type (Fig. 13.15d) [23]. Markers of plasma cell differentiation (CD138) are negative as a rule, allowing a distinction to be made from plasmablastic lymphoma (see Chapter 15).

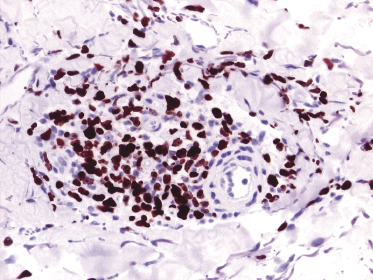

Early lesions with sparse infiltrates display the same phenotype as advanced tumors. A useful marker in this setting is Ki-67, which allows both detection of a high proliferation index inconsistent with inflammatory dermatoses and, due to nuclear staining, also a better evaluation of the size of the nuclei (Fig. 13.16).

Some cases of cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, show an anaplastic morphology histopathologically and expression of CD30 phenotypically [24]. Similar cases arising in the lymph nodes belong to the group of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified, and are classified as the “anaplastic variant” of it [25]. In a similar way, primary cutaneous cases should not be classified separately, but within the group of cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. A better behavior has been reported for nodal cases positive for CD30 [26], but data on cutaneous cases are not available.

In nodal cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Bcl-2 and Myc protein co-expression is associated with a worse prognosis, even in cases where an MYC translocation cannot be demonstrated with standard methods [27–29].

Molecular Genetics

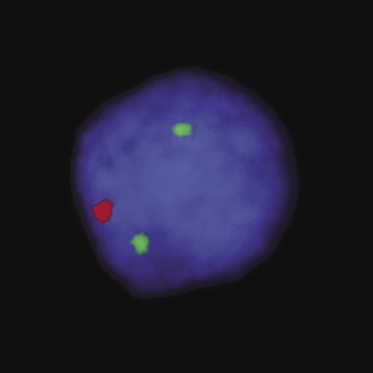

A monoclonal rearrangement of the immunoglobulin (Ig) genes is found in most cases. Analysis of single cells by micromanipulation and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) showed that cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, is characterized by a proliferation of postgerminal center cells [30]. The expression profile is that of activated B-cells with strong expression of the transcription factor MUM-1/IRF4 and constitutive activation of the NF-κB pathway [31]. Hypermethylation of p15 and/or p16 have been observed in some patients with cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, [32]; 9p21 deletions, possibly resulting in the inactivation of p16, have been detected in several cases, and may have a prognostic significance (Fig. 13.17) [33–35].

Overexpression of FOX-P1 is not related to FOXP1 translocations [21]. Other genetic alterations include overexpression of genes associated with cell proliferation, of the protooncogenes PIM1, PIM2, and cMYC, and of the transcription factor Oct-2 [31].

A considerable body of evidence shows that cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, has a molecular profile different from that of cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, diffuse type, thus supporting the classification of these lymphomas into separate categories [31, 34, 36]. As already mentioned, cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, has the gene signature of activated B lymphocytes, whereas follicle center lymphoma displays the signature of germinal center cells [31, 37]. A site-specific expression pattern of some polycomb-group genes, which are involved in the regulation of lymphopoiesis and malignant transformation, has been observed in cases of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas with large cell morphology arising on the head and neck or on the trunk as opposed to those located on the leg, confirming that these tumors represent distinct types of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma [38]. Mutations in the MYD88 gene, a universal adaptor protein involved in the activation of signal pathways including the NF-κB one, are found in the majority of cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, but not in cutaneous follicle center lymphoma [39].

The t(14;18) involving the BCL-2 und IGH genes is not present in cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. A t(14;18)(q32;q21) involving the IGH and MALT1 genes has been detected in one patient, but this case may have represented in truth a secondary cutaneous spread from an extracutaneous B-cell lymphoma [40].

Treatment

If possible, the therapy of choice should be anthracycline-containing systemic chemotherapy combined with anti-CD20 antibody (rituximab) [41–44], but this treatment can be difficult to administer because of the advanced age of most patients (often over 80 years). Age-adapted schemes have been proposed [41]. Rituximab may be used alone, but recurrences are the rule.

If chemotherapy cannot be given, solitary lesions may be treated by radiotherapy. Intralesional interferon-α and antibiotic therapy have also been administered, but nonaggressive options should not be considered if more appropriate modalities can be used.

Prognosis

Cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, has an intermediate behavior, and the estimated disease-specific 5-year survival is 40–50% [44, 45]. Relapse after treatment is common and extracutaneous spread often occurs a few years after onset of the disease. Involvement of the central nervous system can be observed in some cases.

Analysis of prognostic factors is hindered by the fact that in the past cases of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma with large cell morphology belonging to different diagnostic groups (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, and follicle center lymphoma, diffuse type) were lumped together. In this context, reports on a better prognosis of cases with a predominance of cleaved cells over those with a predominance of round cells were due to the inclusion of examples of both lymphoma types in the same category. In a similar way, the prognostic value of Bcl-2 expression observed in the past was due to the fact that Bcl-2 is expressed by cases of cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, but not by those of cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, diffuse type. Other markers discriminating between the two types of lymphoma (e.g., MUM-1) do not have an independent prognostic value [46]. Thus, all of these parameters have no prognostic meaning if cases are classified correctly.

As already mentioned, nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with co-expression of Bcl-2 and Myc proteins is characterized by a worse prognosis [27–29]. Comparable data on cutaneous cases are not available, but due to the similarities observed between nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, positivity for Bcl-2 and Myc should be regarded as a potential indicator of a more aggressive behavior also in cutaneous cases.

The number of lesions at presentation may be related to prognosis in cases of cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type [15]. As already mentioned, cases with deletion of 9p21 seem to be characterized by a more aggressive course [33]. High numbers of reactive, FOX-P3+ regulatory T-cells were related to a better prognosis in one study [47]. In nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, unspecified positivity for CD30 is associated with a better prognosis [26], but data on cutaneous cases are not available.

It should be noted that cases classified as follicle center lymphoma, diffuse type, according to the criteria of the WHO classification, but arising on the legs, have a bad prognosis, similar to that of cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type (see Chapter 11) [15, 48]. Thus, patients with follicle center lymphoma arising on the legs should be managed with the greatest caution, as the behavior may be more aggressive than that of the conventional variant arising on the head and neck area or on the trunk.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree