Chapter 1 A Personal Historical Perspective

Historical perspectives of breast augmentation reflect surgeons’ priorities and focus on the evolution of breast implant devices and surgical techniques. Throughout the history of breast augmentation, surgeons have prioritized and focused on implants and techniques. This focus is ingrained in decades of surgeons by surgical training, a preceptorship learning process that teaches linear thinking based on a problem–solution model. Given a problem—in this case inadequate breast volume—surgeons choose their preferences of implant device and surgical techniques to address the problem. The patient experience, including education, informed consent, recovery, outcomes, and reoperation rates, has largely evolved secondarily and passively as the result of surgeons’ decision processes and choices of devices and techniques. The author’s historical perspective was initially device and technique oriented, but has evolved to become more patient oriented. History suggests that optimal outcomes, safety and efficacy in augmentation prioritize the patient experience and decision processes that determine outcomes. Breast implant devices do not impact patient outcomes as much as surgeon and patient decisions and surgeon execution.

Three Phases Over four Decades of Breast Augmentation

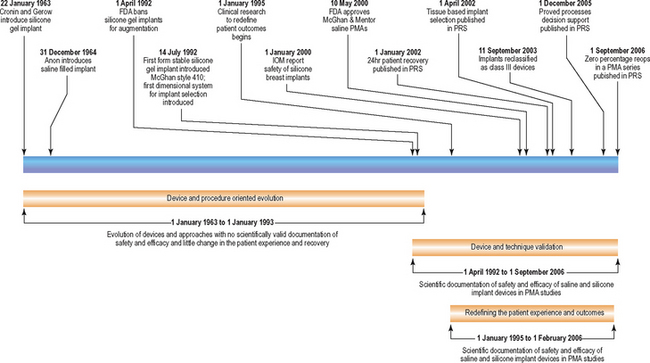

In the United States, the history of breast augmentation can be viewed in three phases or periods: (1) a phase of device and procedure oriented evolution, (2) a period of device and technique validation, and (3) a phase of redefining the patient experience, outcomes, and reoperation rates. While some overlap of these periods exists, these three phases have largely occurred sequentially. Table 1-1 diagrams these three periods and key events that define each phase.

Table 1-1 Historical timeline of breast augmentation.

The following historical perspective is not intended as a comprehensive historical document of breast augmentation or breast implants. The objective of this perspective is to provide insight into the author’s observations, thought processes, and events that influenced the content of this book. A detailed and well documented history of the evolution of breast implant designs is available for interested readers in the Institute of Medicine’s book entitled Safety of Silicone Breast Implants, published in 1999.1 Several authors have attempted to classify breast implant types into specific “generations” of implants. These classifications are arbitrary and non-scientific with respect to outcomes because they classify devices according to device characteristics instead of classifying specific devices according to patient outcomes. Patient outcomes and reoperation rates have varied significantly within certain classes of devices, so global characterization of outcomes by implant class (e.g. textured shell implants or smooth shell implants, generation 1–5, etc.) without specifying the specific product manufacturer, style, and code of device is scientifically meaningless.

1963–1993: Device and Procedure Oriented Evolution

The silicone gel filled breast implant was introduced in 1963 by Drs Cronin and Gerow.2 The author’s perspective based on personal clinical experience with breast augmentation began in 1977 as a plastic surgery resident. At that time, a majority of surgeons performed breast augmentation through an inframammary incision, placing smooth shell, silicone gel filled implants in a submammary pocket location. Capsular contracture rates were high (in the range of 10–15% or more in most practices), but were accepted by most surgeons and patients as an acceptable tradeoff of breast augmentation. Periareolar and axillary approaches to augmentation had been reported, but a majority of United States surgeons used the inframammary incision approach.

In 1981, a fluorosilicone barrier layer was added to the interior walls of implant shells filled with silicone gel in an attempt to limit diffusion of low molecular weight silicone through the implant shell (silicone bleed). This barrier layer, the Intrasheil® barrier, was developed by McGhan Corporation and subsequently licensed to Mentor Corporation for use in their implants. During the 1980s, both McGhan and Mentor Corporations modified shell designs by making shells thicker in an attempt to increase shell longevity.

Several common themes exist in the history of the period from 1963 to 1993. Breast implant designs were largely derived from intuitive perceptions of individual surgeons or breast manufacturer personnel including bioengineers and, in many instances, marketing personnel. Most devices were used under Investigational Device Exemptions (IDEs) or 510k rules that allowed a new device to be classified as roughly equivalent to an existing device. These two sets of FDA rules were very lenient with respect to requiring substantive scientific data in large amounts under clinical review organization (CRO) supervision. As a result, surgeons and manufacturers became extremely complacent during this period and failed to accumulate enough valid scientific data with adequate followup to satisfy the requirements for an FDA PMA study which is the type of study required by the FDA to approve Class III devices such as breast implants.

The moratorium on gel implants for primary augmentation in 1992 resulted from three decades of complacency and business as usual by surgeons and breast implant manufacturers, not recognizing and prioritizing the importance of proactively designing and performing well structured scientific protocols with CRO supervision to assure collection of valid scientific data to address key questions of safety and efficacy. Instead of focusing on this priority, all existing companies during those three decades focused on marketing and remarketing similar implant designs under slightly different forms, calling them “new” products to make them attractive to the surgeon market (a practice that continues today). Not a single breast implant in the period from 1963 to 1991 was subjected to rigorous PMA testing to gather long-term data before the product was released and used in large numbers of patients. The results of this approach were: (a) many products had serious design flaws or high shell failure rates that became apparent after many devices had been implanted in patients (Vogue, Meme, Replicon, Misti Gold, Inamed Style 153, Mentor Siltex salines, PIP prefilled salines, peanut oil filled implants, and others), and (b) negative media and medicolegal consequences arose from untoward outcomes and the result of inadequate testing before bringing products to market. Patient advocate groups, patients, and the FDA became aware of this history and a pattern of introducing devices that had not been adequately investigated prior to market introduction. This awareness has prompted the FDA to be much more stringent with FDA PMA study requirements and require much more data, and longer term data before approving these devices. Although history was clear with respect to evolving concerns about implants prior to 1991, surgeons, surgeon professional organizations, and implant manufacturers did not proactively respond in an effective manner to establish scientifically valid safety and efficacy data for the devices that would satisfy public and FDA concerns about the devices. Had such data been available, the moratorium of 1992 and its effects on options for patients might well have been avoided.

1993–2006: Device and Technique Validation

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree